LU GRAMINATOGGJU

[The wool carding festival]

by Mary Davey

Sardinia

Londra – New York – Pott, Young & Co.

1874

translation of Gallura Tour

I need scarcely describe the stazzu, as in the main it closely resembled other dwellings of the same kind. It was, however, quite of a superior class, and bore many evidences of rustic wealth and even luxury.

I really forget how many “segni,” or heads of cattle, this Leonardo was said to possess, but it was something after the manner of the patriarchs of old. He came up, beretta in hand, bowing profoundly, to meet us, bidding us welcome to his poor dwelling after a most elaborate fashion. He was a fine looking man, taller and with more colour than is to be found in the “Capo di Sotto,” or lower division, of the island, and with a remarkably long shaggy beard and unkempt head of bushy hair. A huge poignard was stuck in his richly embroidered belt, a berude, or lance, in his hand; altogether a formidable looking personage, bearing small appearance of following so peaceful a calling as that of shepherd.

Nevertheless, he spoke after a kind and cordial manner, and invited us with proud humility, to the shelter of his roof. Best, of course, being spokesman, went first, I following, through a large neat enclosure, or court, where a great number of horses were tied to rings in the wall, and were snorting and neighing, kicking and capering, after their most approved fashion.

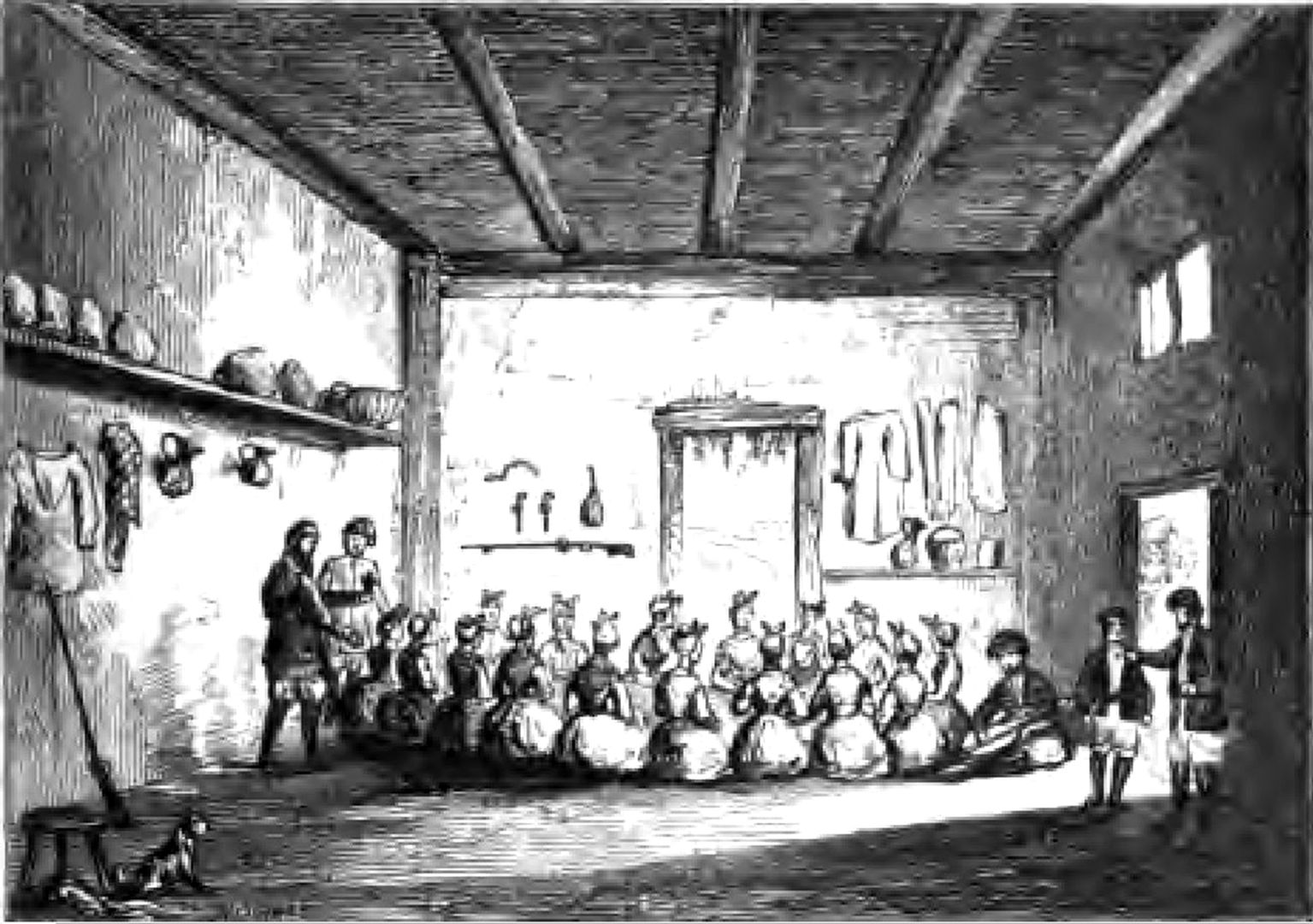

On we went, past a heavy sort of verandah, lined with cork milking pails; and, finally, through the large general apartment, into an inner chamber swept and garnished for the occasion. And what a scene of novelty, brightness, and bustle, it presented.

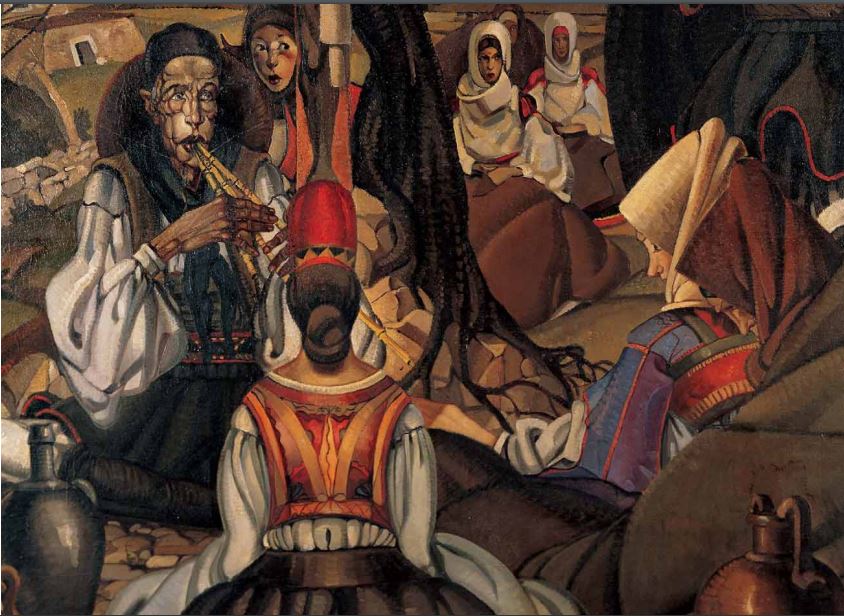

Between twenty and thirty young maidens, in gala costume, the brilliant red and gold of which contrasted most favourably with their olive complexions, and glossy smoothly-braided hair, were sitting in a circle on the ground. They were, of course, laden with jewellery of excellent quality, but of heavy and rather rough manufacture, and each girl had a small bouquet of sweet scented flowers, mostly roses, in her waistband. A great heap of wool was in the midst of them, and this they were picking and teasing with quick and ready fingers.

Beyond these, seated on forms placed against the walls, and forming an outer circle, were the suitors or admirers of the damsels, one of whom at the moment we entered was playing a national air on that wonderfully antique piping instrument known as the lannedda. It was a pretty scene, much after the fashion of the American “bee.” These merry people had assembled to assist the shepherd’s wife to prepare her wool for the subsequent process of spinning and weaving into orbacci-the home-spun cloth of the country, and used entirely by both the upper and lower classes of peasantry.

There was a little lull in the work and a gaze of curious enquiry as we entered, which suddenly changed into a series of bright smiles of recognition as Best made his appearance, and “Serbiridos Signore” echoed on all sides.

Best looked very beaming and hand some. I thought, as he gracefully returned the salutation. His clear blue eyes and waving brown hair formed such a contrast with the dark skinned Sards. He seemed generally known, and had some little word or joke with most of them.

“Take care, Charley,” he said, addressing me, “mind you distribute your attentions pretty generally, for if, by chance, you should centre them in too marked a manner on any one of these gentle damsels you may chance to have one of those fierce daggers in your ribs. No people under the sun are so jealous as Sards; they beat Italians hollow, and that is saying much.”

The gay young wool-pickers made a jabbering mimicry of our language, so new to their ears. Then came a peal of laughter. The wife of the shepherd next made her appearance, all brilliant in smiles and gold ornaments, three shy little bronzed creatures hanging by her skirts, all intent on a good view of Bertoldo’s wonderful Milordi Inglesi.

By-and-by silence was restored, the launedda piped up again, and the wool-picking went on with redoubled vigour. At a given signal one of the maidens-a very pretty one, by the way, rose up, and, after some tittering and rustic coquetry, she took a queer looking guitar, called a cither, in her hand, played some tinkling sort of rondo; then bursting forth into a wild sort of recitative, she accompanied her voice by some simple but not discordant chords.

The words were soft and melodious, the girl’s voice rich and full. Her whole figure and “pose” graceful. Scarcely had she finished, when another, and again another in her turn took up the cadence until each one had contributed her quota to the general amusement, with more or less skill and grace. This done, the young girl who had first sung, whose name was Teresa, and who appeared to be the acknowledged belle of the party, again rose, and, advancing timidly, presented her bouquet to a pleasant looking young fellow, dressed in the garb of a husbandman (coltivatore), at the same time accompanying the gift with half a verse.

The young man bowed low as he took the nosegay from her hand, and completed the couplet. The beautiful Sard dialect-composed variously of Italian, Spanish, and, in some districts, even of Arabic and Latin-is very easily adapted to this sort of impromptu versification, and the vein of innate poetry is soon aroused in the Sard breast. As before, the other maidens each in her turn followed Teresa’s example, until all had presented their bouquets to their respective swains. The wool-picking meantime pro gressed rapidly. The full baskets of prepared wool were conveyed away; the heap was waning perceptibly.

Best set himself to work quite handily, and made a finish to a couplet, when the little daughter of the shepherd presented him with some splendid lilies of the valley.

But, amid all this apparent gaiety, a cloud hung on the spirits of the party. Teresa had many admirers-too many by half, so that her preference for a simple coltivatore aroused a pang of jealousy in more than one bosom; but chief among these discontents was one Ignazio, a fierce looking young bandit, who, being the eldest son of a very wealthy shepherd, could ill brook a rival, and most especially one of a condition beneath his own. He scowled darkly on the happy looking young Felice, who, holding the prized bouquet in his hand, was whispering soft nothings in the ear of the pretty Teresa.

“That fellow means mischief, I really believe,” whispered Best in English, “the sullen scowling wretch, no wonder the girl prefers yonder bright looking youth, Felice, who is about as handsome a looking fellow as one ever sees in Sardinia; but so it is-Ignazio is rich-it’s the old story; and I should never wonder if he were to lie in wait for his handsome rival, and just plant that glitter ing dagger of his in his heart some fine starlight evening. Oh! Campana is right; the laws here are wofully inefficient, and often cruelly unjust; so, until everything is really amended, there is little hope of peace and goodwill and that kind of thing.

[…] Meantime, there was an atmosphere of un easiness; young men spoke to each other in an under tone; the girls were looking pale and disturbed. The hostess did her best to set people at their ease. She spread a bountiful feast of good things, maccaroni and cheese, delicious fruits and confections, the whitest of rolls of bread, the most delicious of wines.

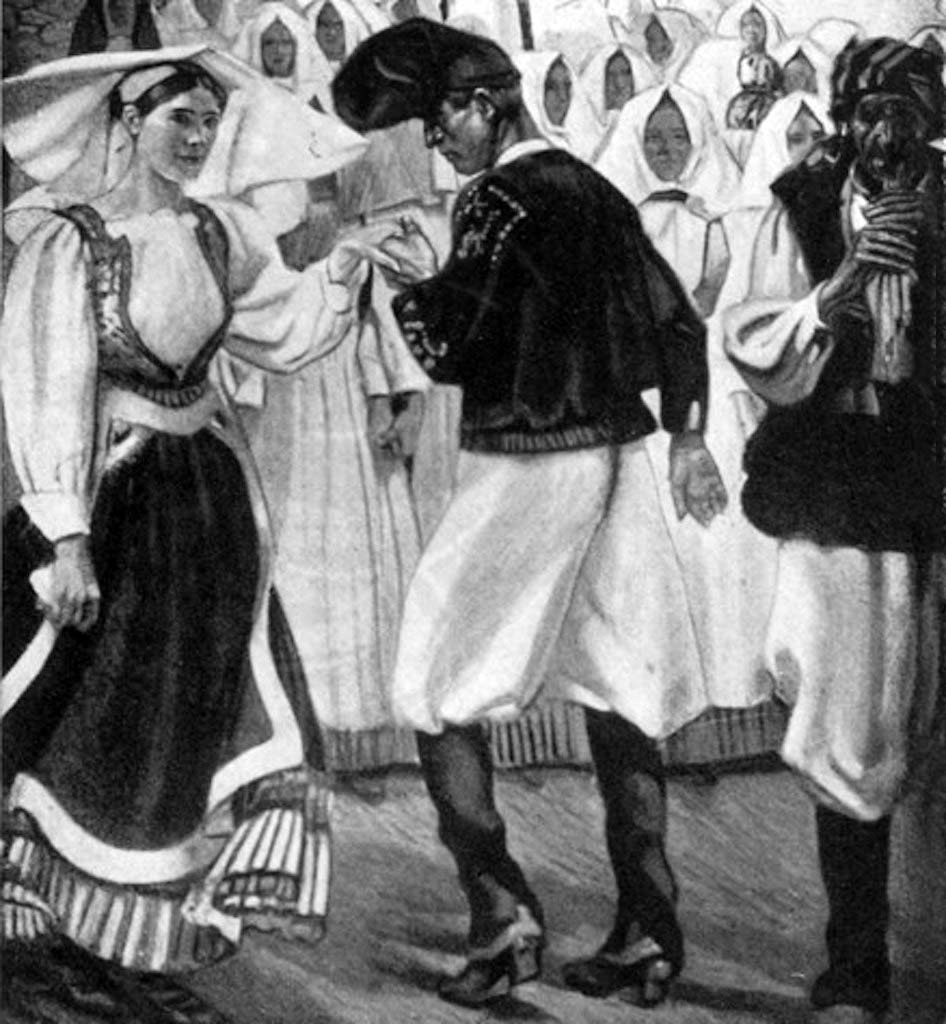

After the refreshment, the young folk lost no time indoors; the evening was cool and serene, they flocked into the court yard, and were soon deep in the whirl, whirl, tramp, tramp, of the various ballo-tondo. Best was in the centre of the mysterious ring, winding away, apparently with the utmost enjoyment.

Took my seat with the host and hostess, the priest, and a select assemblage of village crones on sun dry benches, and reversed wine casks, just beneath the heavy verandah of the stazzu. Of course I did my best to make myself agreeable, and by dint of smiles, shrugs, and gesticulations, with a little very indifferent Italian, and as many Sard words as I could by any possibility muster, to make myself intelligible.

The evening wore on, the stars which look so large and bright in the clear purple of a southern sky redeemed the night from darkness, but there was no moon, and not a lamp had as yet been lit. Leonardo had stretched himself on his bench and was in a sound sleep, when suddenly a fierce yell rang clear and distinct above every sound. The dancing ceased, the central group of choristers was transfixed and silent, their eyes and mouths open. What could it mean? Ignazio, the fierce young bandit shepherd, had burst from the ring, he stood midway between the dancers and the bystanders, or sitters, pale with rage, foaming and furious.

A torrent of words and angry gestures followed, he pointed to Teresa and Felice. The priest arose from his seat, pale as death, made the sign of the cross, and, going up to the frantic youth, used every argument to pacify the storm of wrath. It seemed useless. Ignazio tore away, bounding like a goat, untied his horse, leaped from the horseblock to the saddle, and away over rock and glen like a spirit of darkness. A storm of inter jections in every key followed, invocations, appeals to the saints, sighs and tears.

In the midst of the confusion Best stole to my side. “What’s the matter?” I enquired.

“Why, just this; that fiend Ignazio, perceived that yonder pretty maiden, Teresa, permitted Felice, the young husbandman, to clasp her hand in the dance palm to palm, instead of merely en twining the fingers, which is the usual way. Now, joining palm to palm means that she accepts him as her lover. Hence his indignation. There will be blood spilt, or I am much mistaken; but come, let us away. It is sickening to witness such scenes of dire and dreadful discord.”

Teresa was in tears, young Felice, erect and manly, but pale and thoughtful, was standing by her side, offering what consolation he might. Leonardo, thoroughly roused up, looked fierce and indignant; the man had eaten of his salt, and had brought tumult and confusion to his roof tree. The women were scared; the priest strove to restore peace. Best, with all an Englishman’s true kindness of heart, went straight up to Felice, bade him be of good cheer-the maiden loved him, and with time all might be well. Poor Felice shook his head, but smiled out his thanks. We bowed to all and departed.

Many immediately followed our example, and the narrow mountain path was alive with horses; the girls sitting on their little pads behind their gay and stalwart cavaliers. The fire flies danced in the clear night air, the frogs croaked in the valleys, the owl screeched in the tall cork trees.

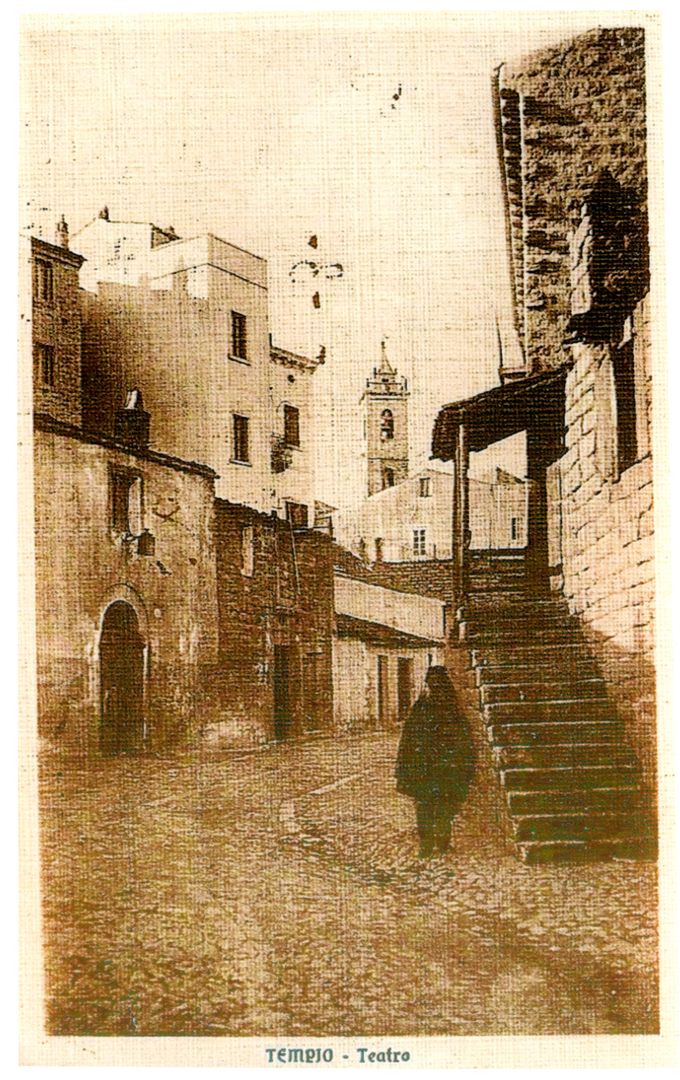

It was getting late when we clattered into the quaint looking old streets of Tempio, and it was curious to see the slight girlish forms startled away from the clumsy balconies where they had been holding sweet converse with their affianced lovers; to hear the rapid closing of casements, and to note the retreating forms of their admirers stealing up narrow alleys or shady streets.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Drawings, paintings and lithographs from the 19th century

Giuseppe Cominotti e Enrico Gonin [drawing], A.J. Lallemand [engraving], Graminatorgiu, ca 1826-1839, IN Alberto De La Marmora, Voyage en Sardaigne, ou Description statistique, phisique… Atlas de la première partie, 1. ed. Paris, Delaforest 1826; 2. ed. Paris, Bertrand – Turin, Bocca,1839.

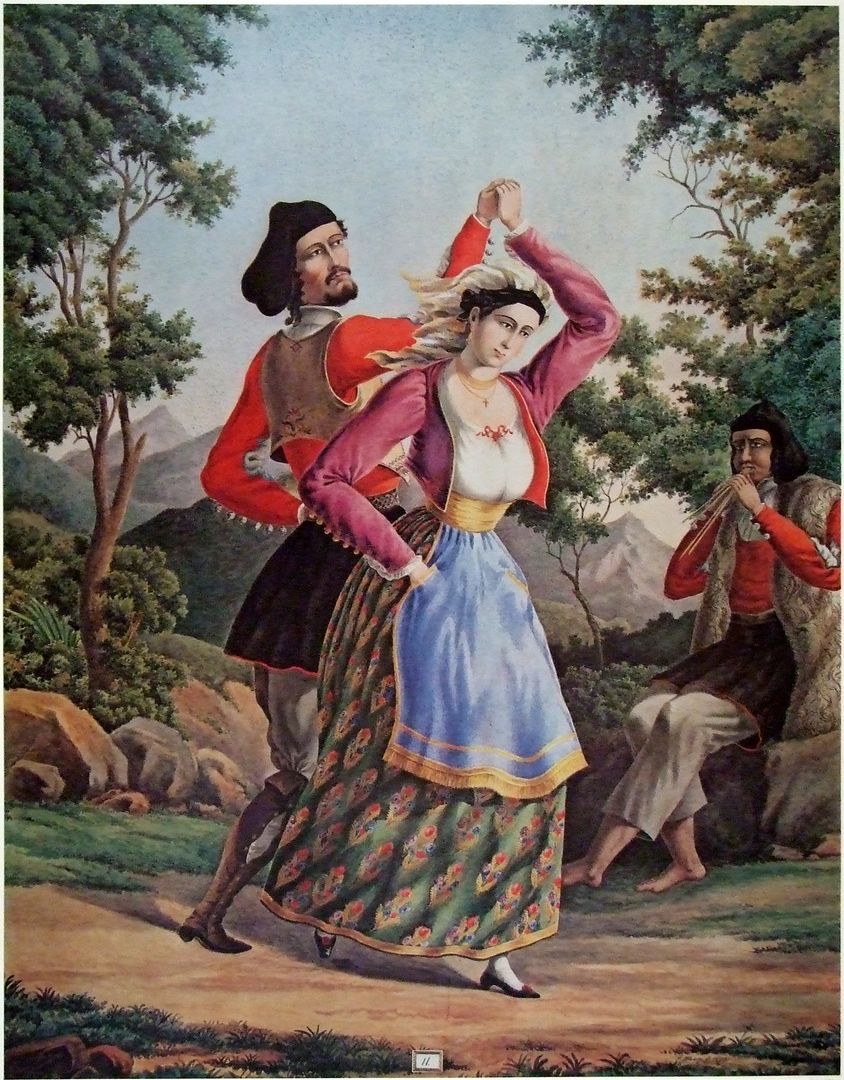

Alessio Pittaluga, “Shepherd of Gallura”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes, par A. Pittaluga, [litografia incisa da Philead Salvator Levilly], Paris, chez Marino; Firenze, Antonio Campani, 1826 (rist. Carlo Delfino 2012).

Jean Baptiste Barla, “Wealthy man from Tempio”, 1841 (coll. Angelino Mereu): https://amerblog.wordpress.com

Giuseppe Cominotti e Enrico Gonin [drawing], A.J. Lallemand [engraving], Vestimenti sardi in serie èSardinian clothing in a series] – Tempio, ca 1826-1839, IN Alberto Della Marmora, Voyage en Sardaigne cit.

Philippine de La Marmora, Tempio woman, IN Luigi Piloni, Memorie sulla terra sarda: tempere inedite di Philippine de la Marmora (1854-1856), Cagliari, Fossataro, 1964.

Mario Delitala, Launeddas players, 1923.

Bernardino Palazzi, Launeddas player.

Filippo Figari, Launeddas player, 1916.

Lorenzo Pedrone, Shepherd of Gallura, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Giuseppe Cominotti e Enrico Gonin [disegno], A.J. Lallemand [incisione], Sardinian dance (or round dance), northern area of Sardinia, IN Alberto Della Marmora, Voyage en Sardaigne cit.

Luciano Baldassarre, Round dance, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna cit.

John William Cook, Graminatorgiu at Tempio, ca 1849, IN John Warre Tyndale, The Island of Sardinia, London 1849, ed. italiana L’isola di Sardegna, Nuoro, Ilisso, 2002.

Postcards and photos from the 19th and early 20th century

coll. Erennio Pedroni, Gianfranco Serafino, Vittorio Ruggero.

Contemporary photos

Hans Leysieffer – Flickr.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED