TEMPIO

by Thomas Forester

Rambles in the islands of Corsica and Sardinia

London 1858; 1861

Longman. Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts

in italian: ![]()

The replies of the courier to our inquiries after a hotel had left a complete blank in our prospects of bed, board, and lodging at the end of our journey. For travellers, such as ourselves, there was no accommodation. Tempio was rarely visited by strangers.

This looked serious, after a mountain ride of nearly thirty miles, and between nine and ten o’clock at night; – what was to be done? We had letters of introduction to persons of the highest distinction in the place, but they hardly warranted our intruding ourselves on them, hungry, travel-stained, and houseless, at that late hour. The case, however, being desperate we decided, at last, on presenting ourselves to the Commandant of the garrison, as the most likely person to give or procure us quarters.

Thus we traversed the whole city, the Commandant’s mansion lying at the furthest extremity.

Our tramp roused to attention a drowsy sentry at the gate; there were lights à la prima, the family then had not retired for the night. The strange arrival is announced, and our viandante makes no scruple of depositing our baggage in the hall.

The Commandant receives us with politeness, regrets that he is so straitened in his quarters that he cannot offer us beds, and sends an orderly who procures us a lodging, meanwhile giving us coffee.

Thus we traversed the whole city, the Commandant’s mansion lying at the furthest extremity.

Our tramp roused to attention a drowsy sentry at the gate; there were lights à la prima, the family then had not retired for the night. The strange arrival is announced, and our viandante makes no scruple of depositing our baggage in the hall.

The Commandant receives us with politeness, regrets that he is so straitened in his quarters that he cannot offer us beds, and sends an orderly who procures us a lodging, meanwhile giving us coffee.

We are installed by the mistress, a shrewish person, who, making pretensions to gentility, receives her guests under protest that she does not keep a hotel, but is willing to accommodate strangers, a phrase repeated a hundred times while we were under her roof, and emphatically when presenting a rather unconscionable bill on our departure.

And this was the only refuge in a city of from six to eight thousand inhabitants, many of them boasting nobility, the capital of a province, the seat of a governor and a bishop, and headquarters of a military district.

I may be pardoned for being circumstantial in details giving an idea of what travelling in Sardinia is. Things are much the same throughout the island. The tourist who sets foot on it must be steeled against brigands, vermin, intemperie, and indifferent fare. “Per aspera tendens” would be his suitable motto. He must be prepared to rough it.

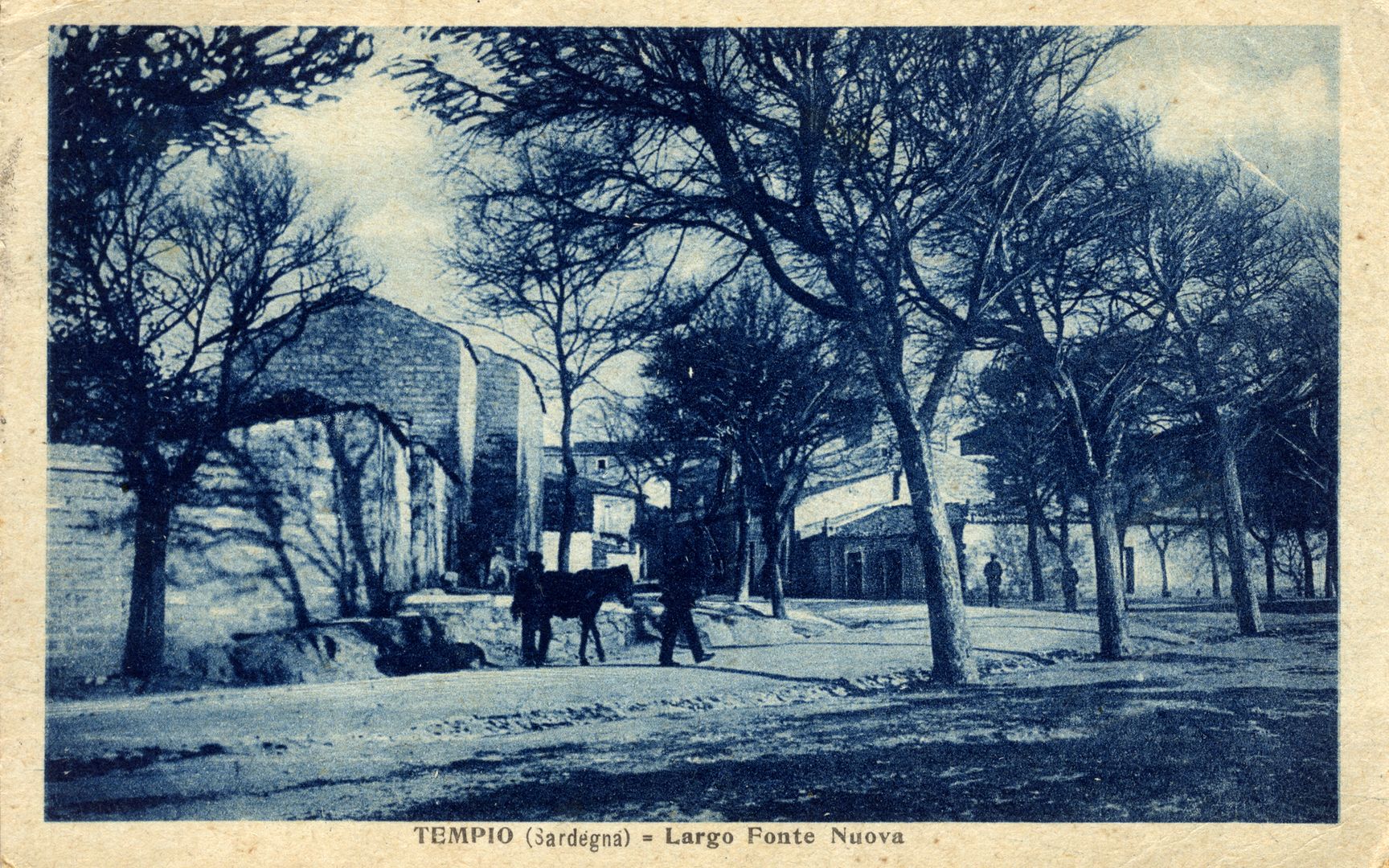

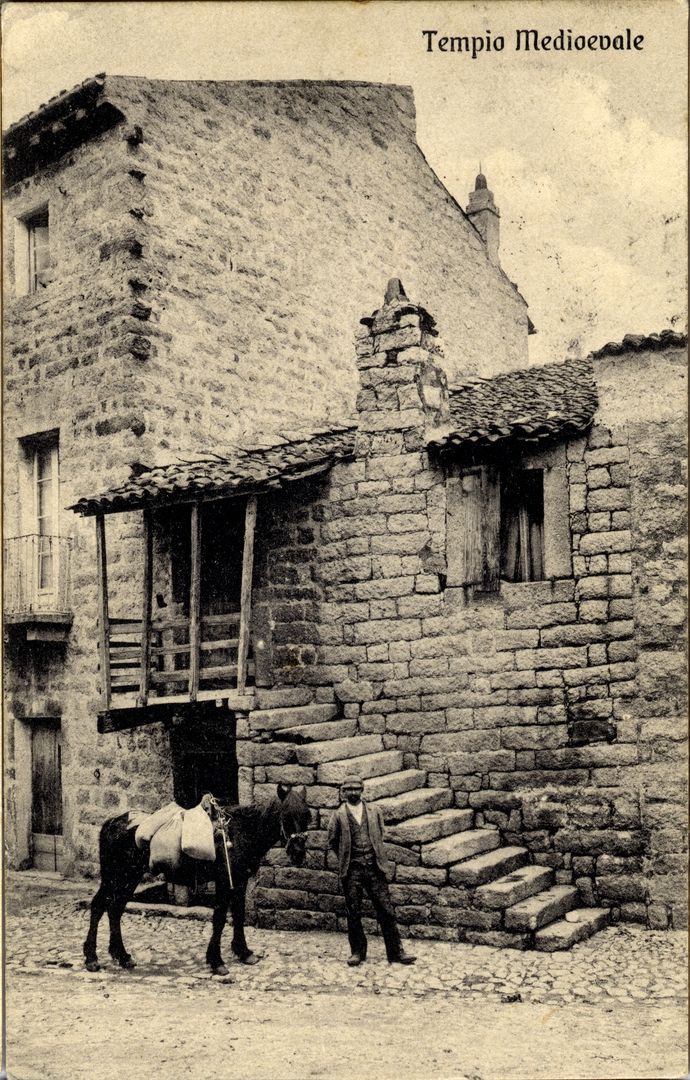

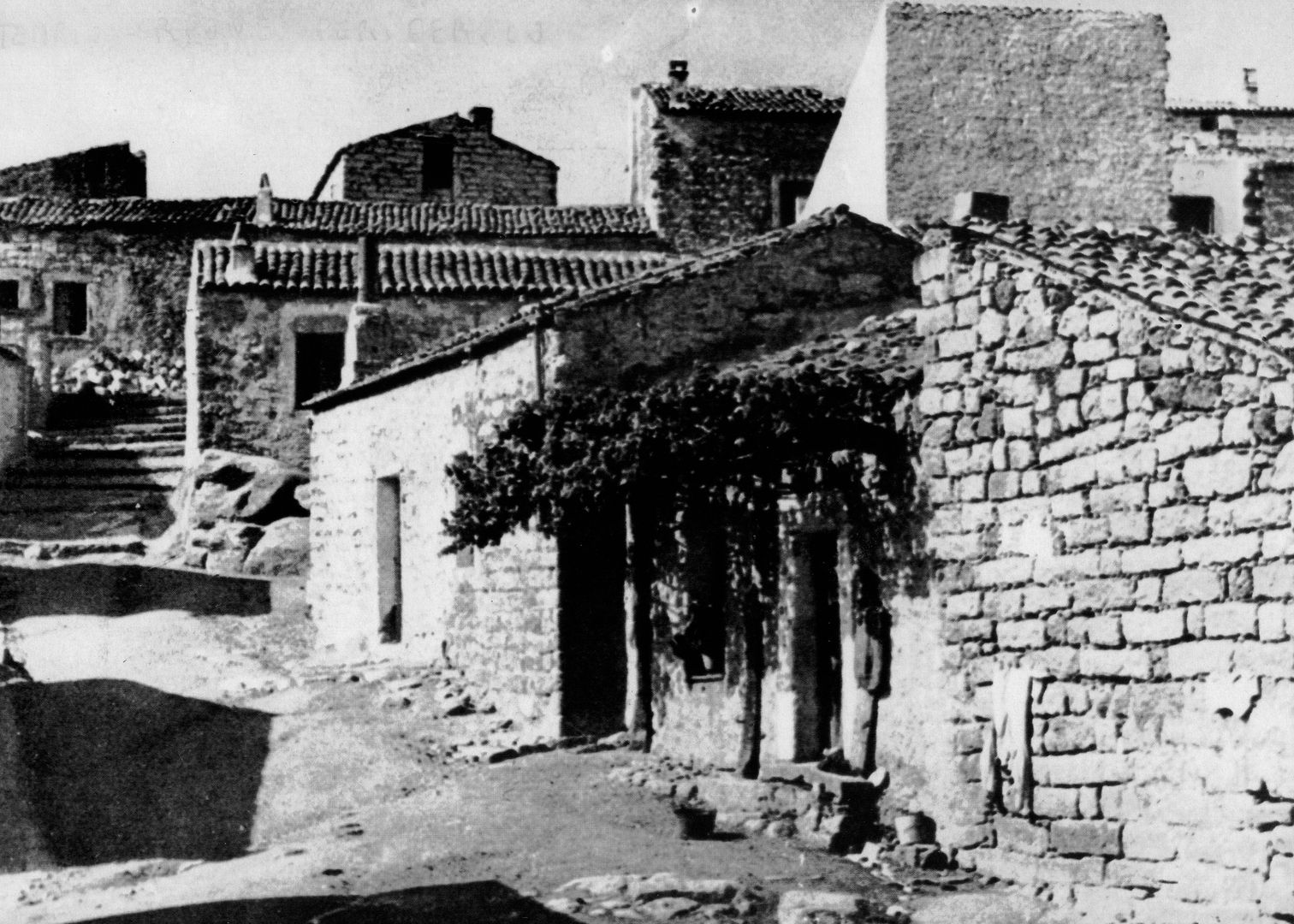

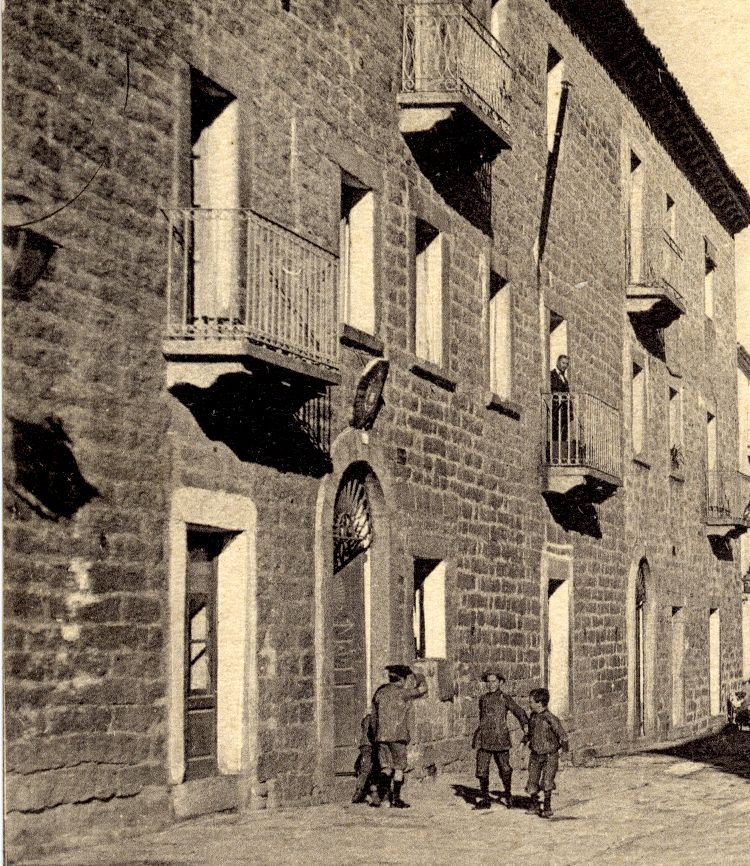

Daylight, indeed, failed to improve the internal aspect of the place, but rather disclosed the filth of the narrow streets, without entirely dissipating the gloom shed upon them from the dusky granite of which the buildings are constructed, and the heavy wooden balconies protruding over the thoroughfares.

The houses have, however, a substantial air, some of them are stuccoed, and Tempio can even boast its palaces of an ancient nobility, with coats of arms sculptured in white marble over the entrances.

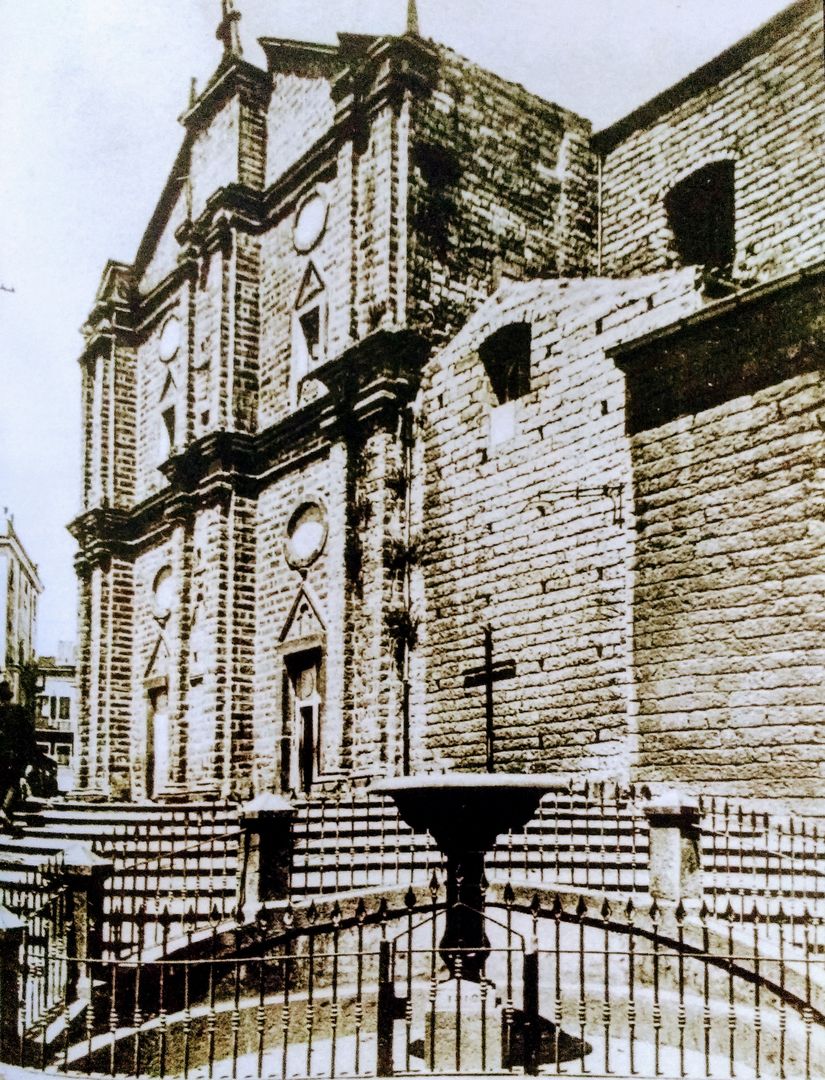

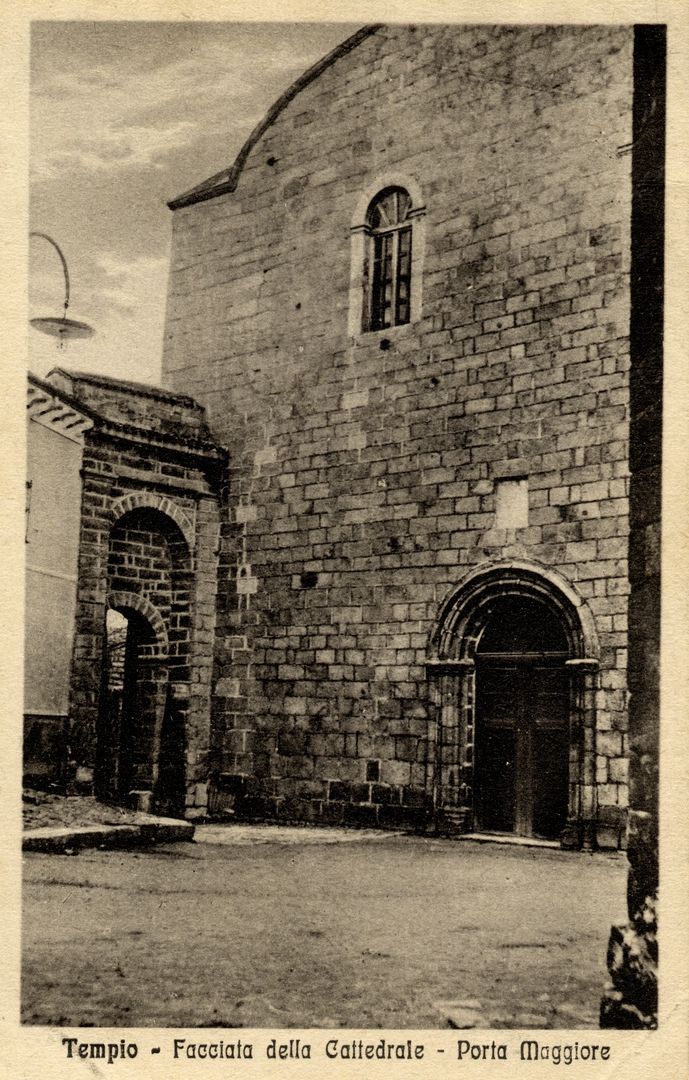

The foundation consists of a dean and twelve canons, with eighteen other inferior clergy. Since 1839 it has ranked as a cathedral, Tempio having been erected into a see united with those of Civita and Ampurias, and the bishop residing here six months of the year.

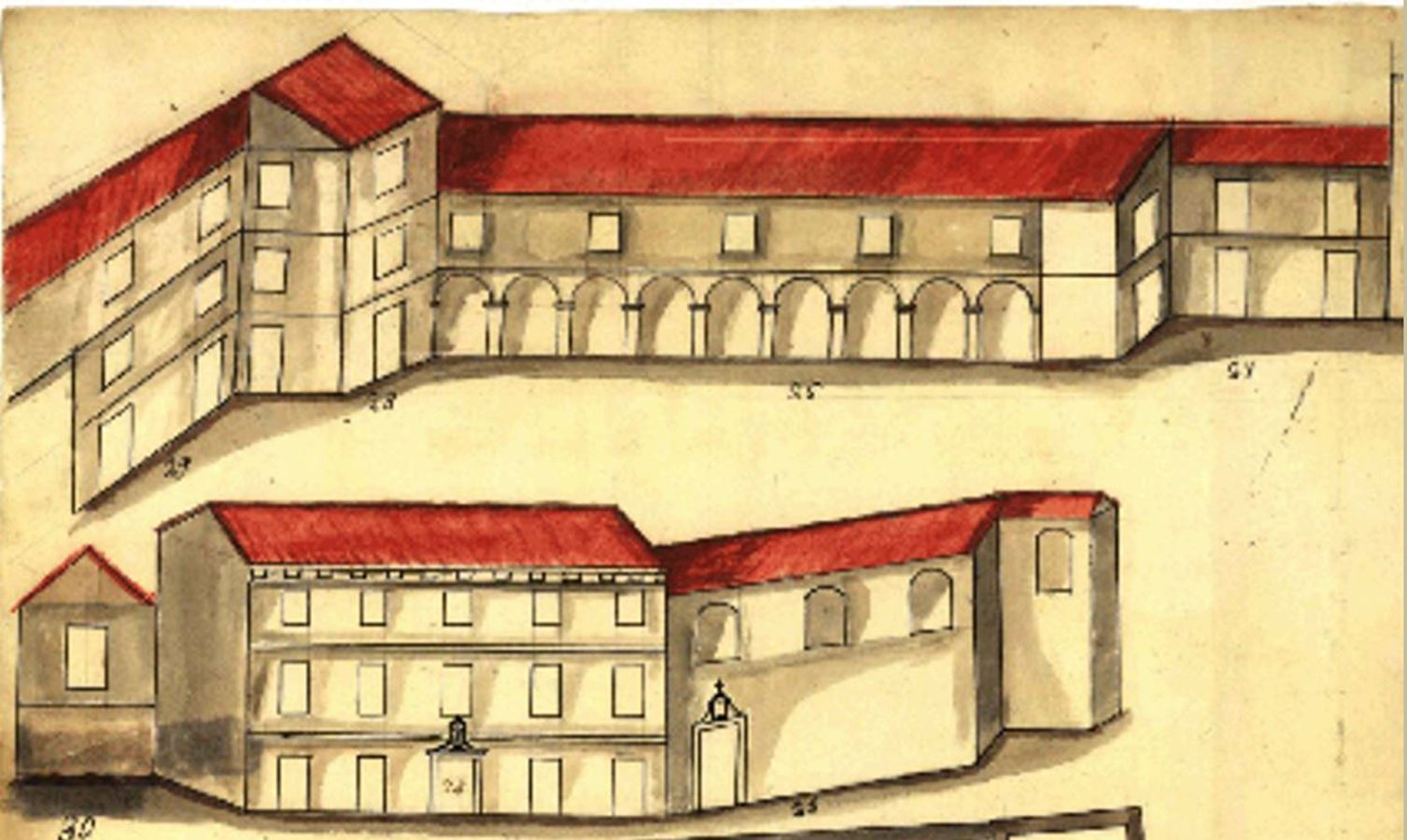

There is a massive old nunnery, now, I believe, suppressed, in the centre of the place, and outside the town a reformatory for the confinement of criminals sentenced to secondary punishment, a large building with a handsome elevation.

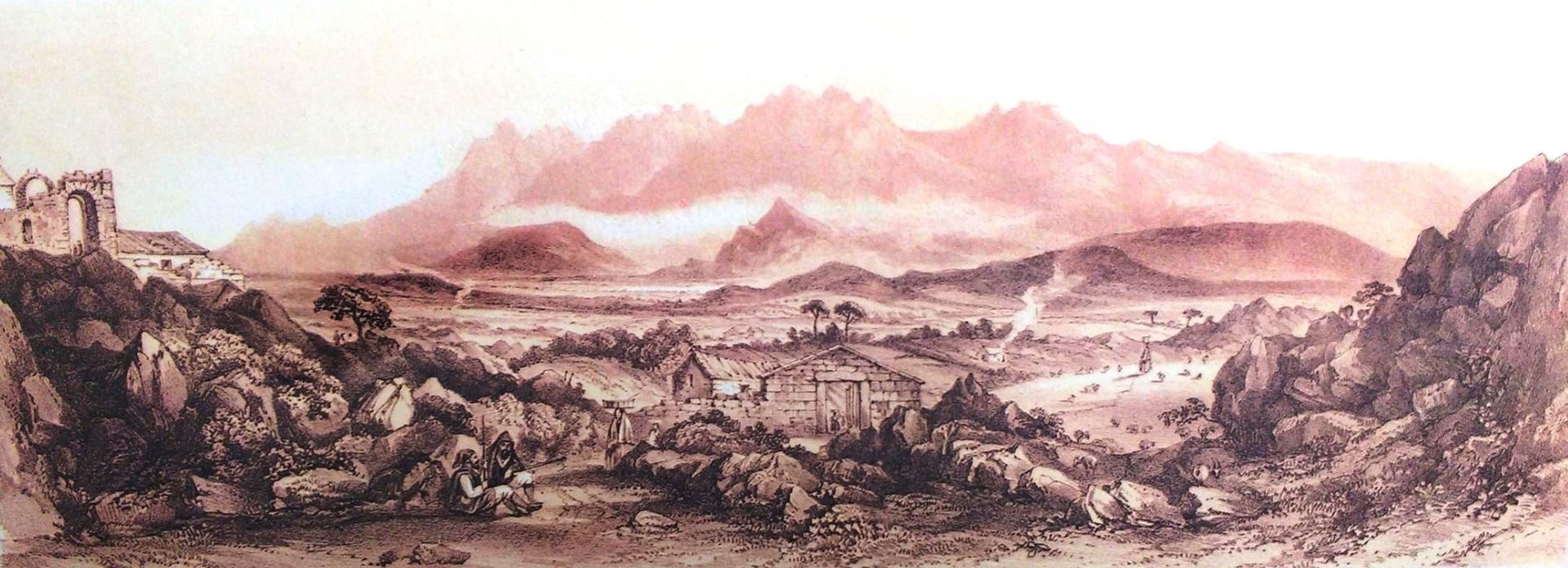

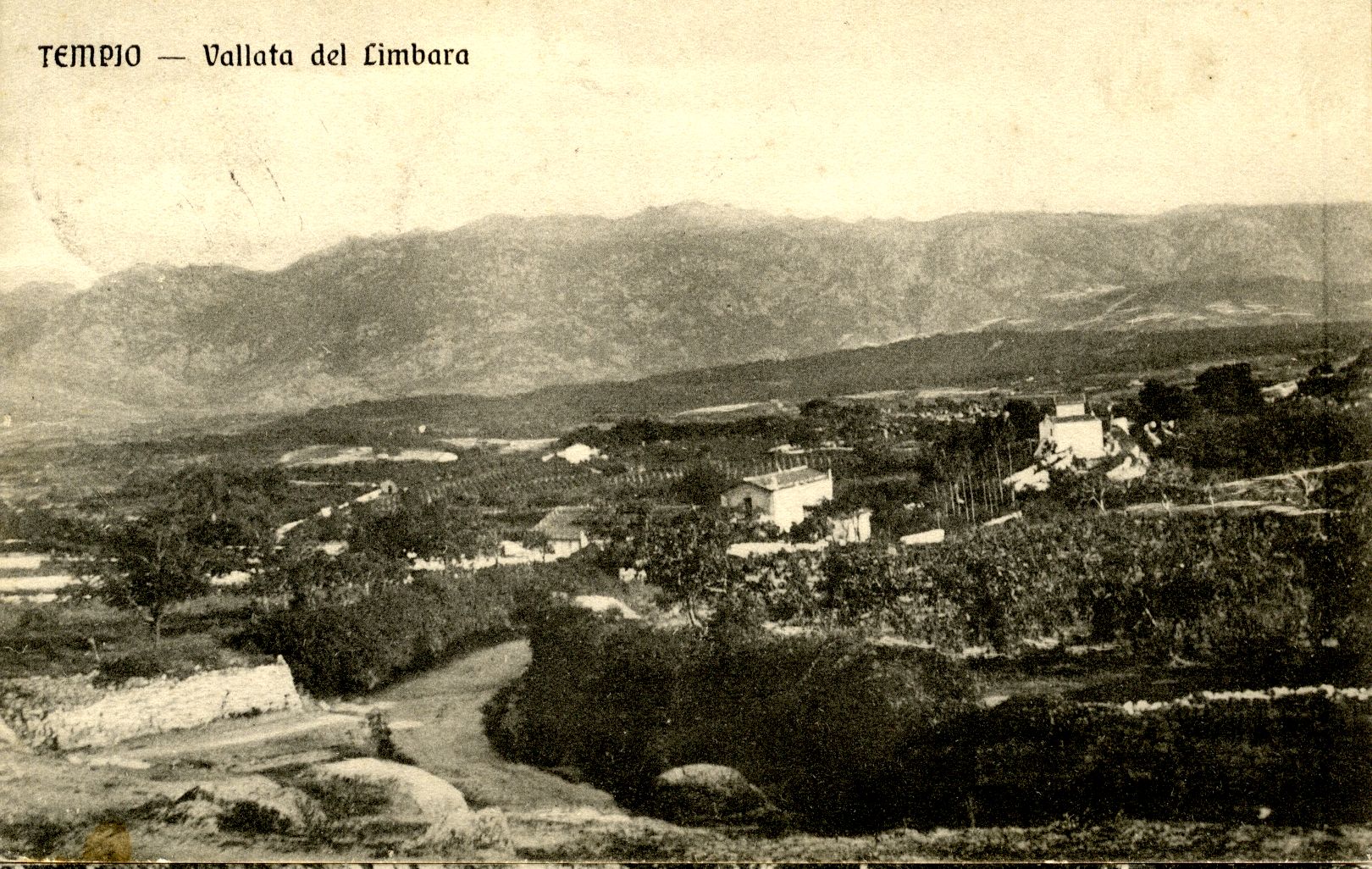

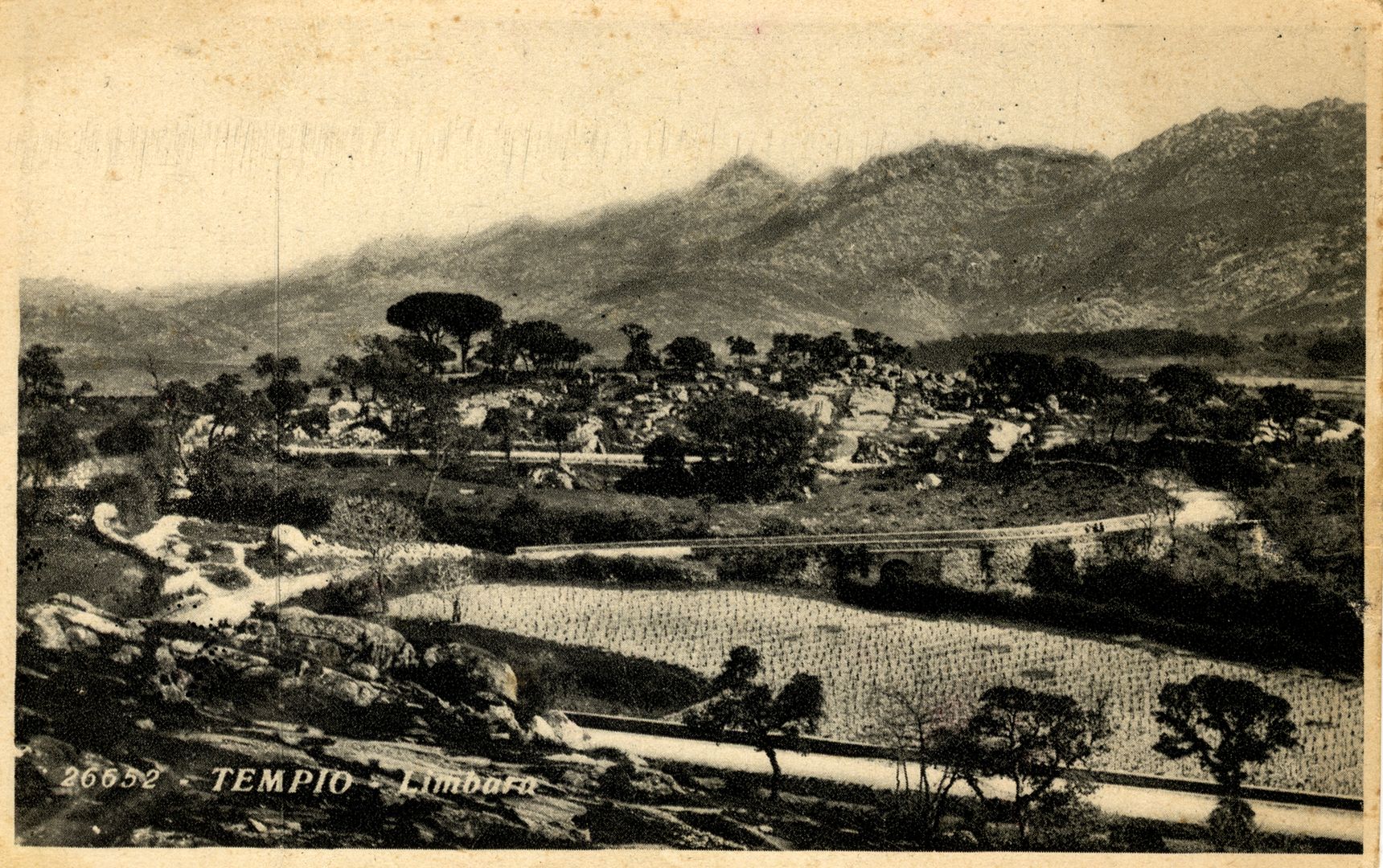

Placed on a gentle swell of the wide undulating plain already mentioned the Gemini plain, a plateau of nearly 2000 feet above the level of the sea, it stands midway between two grand mountain ranges, the Limbara stretching the bold outlines of its massive forms in a course south of the town, its summit rising to 4396 feet; and, to the north-east, a chain not quite so elevated, but of an equally wild and irregular formation, and presenting to the eye, when viewed from Tempio, even a more rugged and serrated ridge. The defiles of this chain we passed in approaching Tempio; those of the Limbara were to be penetrated in our progress southward.

Its high situation and exposure render Tempio healthy, and it is even said to be cold in winter, of which we found no symptoms in the month of November, when Limbara is supposed to assume its diadem of snow, retaining it till April.

It combines great breadth, striking contrasts, and a most harmonious blending of colour. For a wide circuit round the town, gardens, orchards, vineyards, and a variety of small inclosures, occupying the slopes and hollows of the undulating surface, and well massed, give an idea of fertility one should not expect at this elevation.

Here and there, a single round-topped pine, or a group of such pines, crowns a knoll, and breaks the flowing outlines. The open pastoral country beyond is linked to this cultivated zone by detached masses of copse and woods of cork and ilex, extending to the base of the mountains.

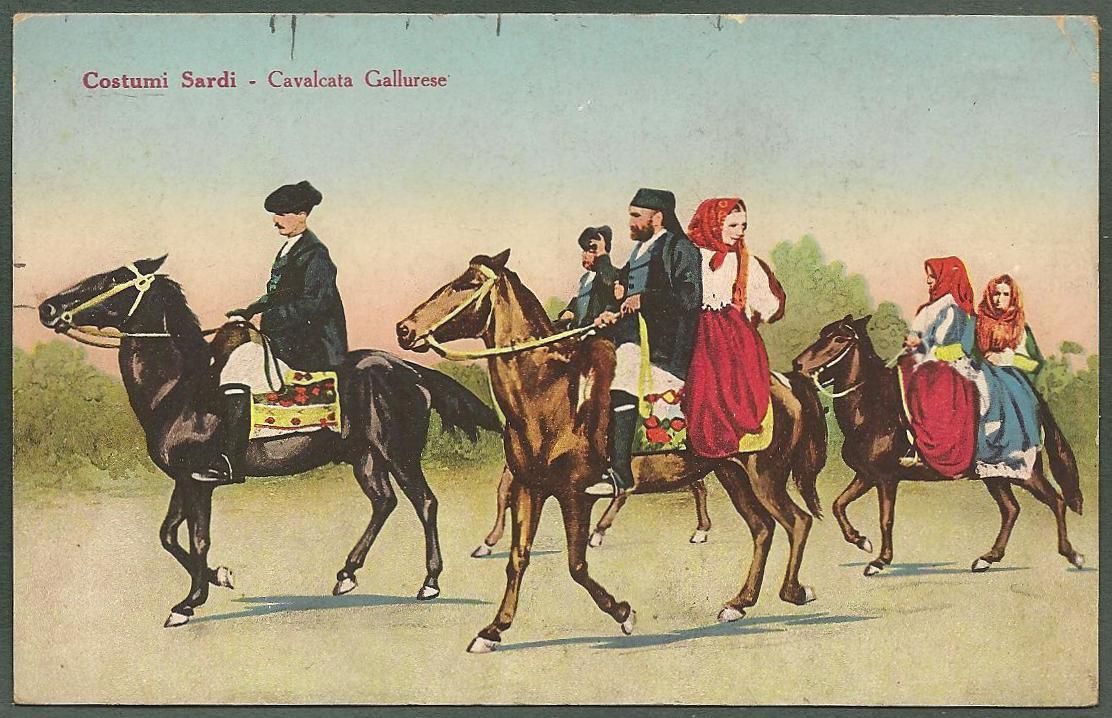

[Taken from another paragraph: A curious instance of this occurred at Tempio. We had made a bargain, on his own terms, with one of these people, for horses to proceed on our route, and they were brought to the door ready for loading up and mounting, when the cavallante refused to allow our using our English saddles. Not wishing to lose time, we took considerable pains to point out that the saddles being well padded would not wring his horses’ backs, conceiving that to be what he apprehended. But it was to no purpose; there seemed to be no other reason for the scruple than that a Sarde horse must be caparisoned à la Sarde, with high-peaked saddle and velvet housings. The cavallante, persisting, led his horses back to the stable, losing a profitable engagement rather than being willing to submit to their being equipped in a foreign fashion. After a short delay we procured others from a cavallante who made no such difficulties, and proved a very serviceable and attentive conductor].

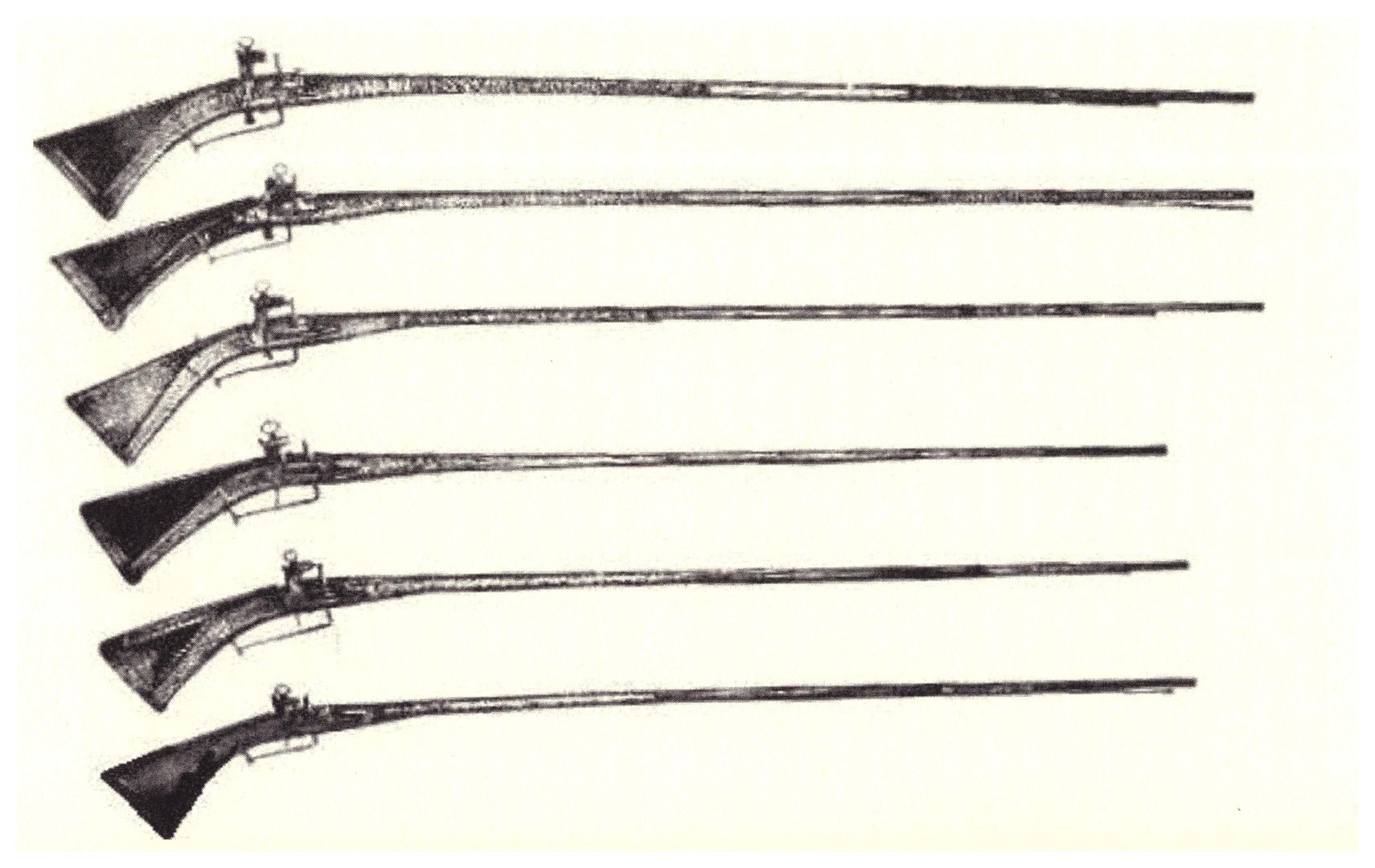

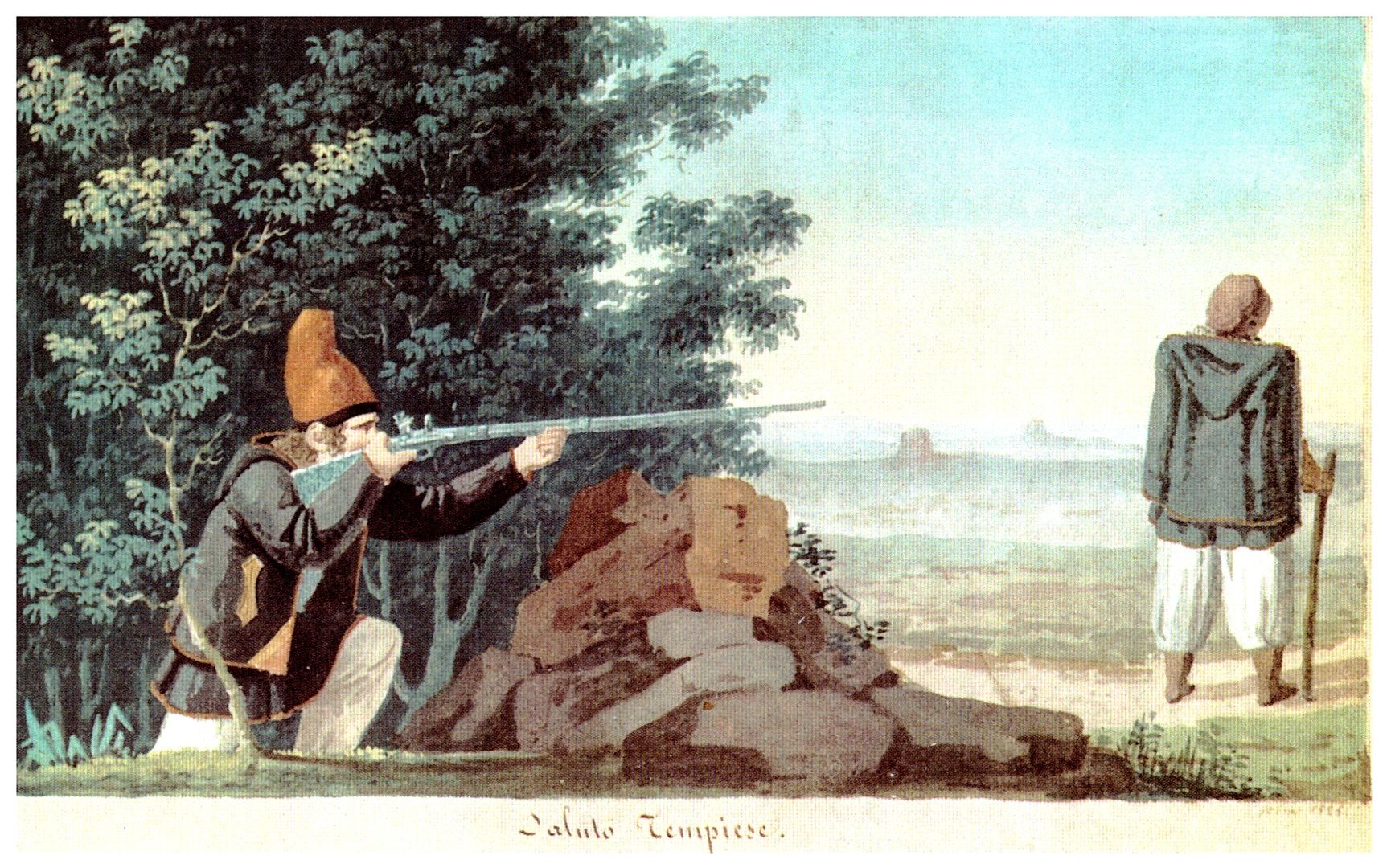

They manufacture here the best guns in Sardinia, and know how to use them; being capital sportsmen, cacciatori, as well as formidable enemies in the vindictive feuds for which they have been celebrated, and not yet entirely extinct.

Returning one night from the Casino, in company of the Commandant, he stopped on the piazza in front of the cathedral and related to us the circumstances of an assassination perpetrated a short time before on the very steps of the church.

Sardinia returns twenty-four members to the national parliament at Turin. The ecclesiastical jurisdiction is administered by three archbishops, filling the sees of Cagliari, Sassari, and Oristano, and eight bishops, seated in the other principal cities. High official appointments at Tempio are not very enviable posts; governors and commandants not being exempt from the summary vengeance, for real or supposed wrongs, at which the Sardes are so apt.

The Commandant told us that his immediate predecessor had received one of the death-warnings which precede the fatal stroke: I believe he was soon afterwards removed. For himself, his successor said, he took no precautions, did his duty, and braved the consequences. A few years before, the Governor, baling compromised himself by acts of injustice, was assassinated, after receiving one of these “death-warnings” peculiar to Sardinia. During the night he heard a pane of glass crack, and on examining it in the morning he found the fatal bullet on the floor. The custom of the country is that, whenever the vendetta alla morte, revenge even to death, is to be carried out, the party avenging himself shall give his adversary timely notice by throwing a bullet into his window, in order that he may either make immediate compensation for the injury or prepare himself for death. The Governor for some time used every caution as to when and where he went, but at length disregarded the warning, imagining he was safe. The assassin, however, had watched him with an eagle’s eye, and lie fell in a moment he least expected. Report further says – observes Mr. Tyndale – in whose words we relate the occurrence, “that he is not the only Governor of Gallura to whom this summary mode of obtaining justice, or inflicting vengeance, has been intimated.”

The present Intendente of Tempio, the Marchese Clavarino, though he only entered on his office in the month of April before our visit, had already done much by his firm and enlightened administration to restore order and confidence. He had been able to collect the arrears of taxes, and, by impartial justice between all factions, had removed every pretence for a resort to deeds of violence for the redress of injuries.

“The Governor’s palace, establishment, and retinue,” observes Mr. Tyndale, “consist of three rooms on a second story, a female servant, and a sentry at the door.” Things were little changed in 1853, but, in the absence of all state, we were impressed on our first visit of ceremony that the government of a turbulent province could not have been intrusted to better hands. In the antechamber we found a priest waiting, as it struck me from his deportment, to prefer his suit with “bated breath,” and the feeling that the wings of the priesthood are now clipped in the Sardinian states.

The Marquis conversed with frankness on his own position and the state of the island. He had been in London at the time of the “Great Exhibition,” and his views of the English alliance, and of politics generally, were just such as might be expected from an enlightened Sardinian. A worthy coadjutor to such statesmen as D’Azeglio and Cavour, I would venture to predict that the Intendente of Tempio will ere long be called to fill a higher post.

A very considerable extent of surface is planted with vines, divided, however, into small vineyards. At the entrance of each stands an arched gateway, generally a solid structure of granite, with more or less architectural pretensions, and a date and initials carved in stone, commemorative, no doubt, of the planting of so cherished a family inheritance. One of these is represented in the foreground of the accompanying plate.

Sheltered by these in the heat of noon, and in still greater numbers at eventide, one saw the damsels of Tempio resort with their pitchers, as in ancient times Abraham’s steward, in his journey to Mesopotamia, stood at the well of Nahor, when the daughters of the men of the city came out with their pitchers; as Saul, passing through Mount Ephraim and ascending the hill of Zuph, met the maidens going out to draw water; or as the spies of Ulysses fell in with the daughter of Antiphates at the well of Artacia. Sardinia abounds with such mementos of primitive times.

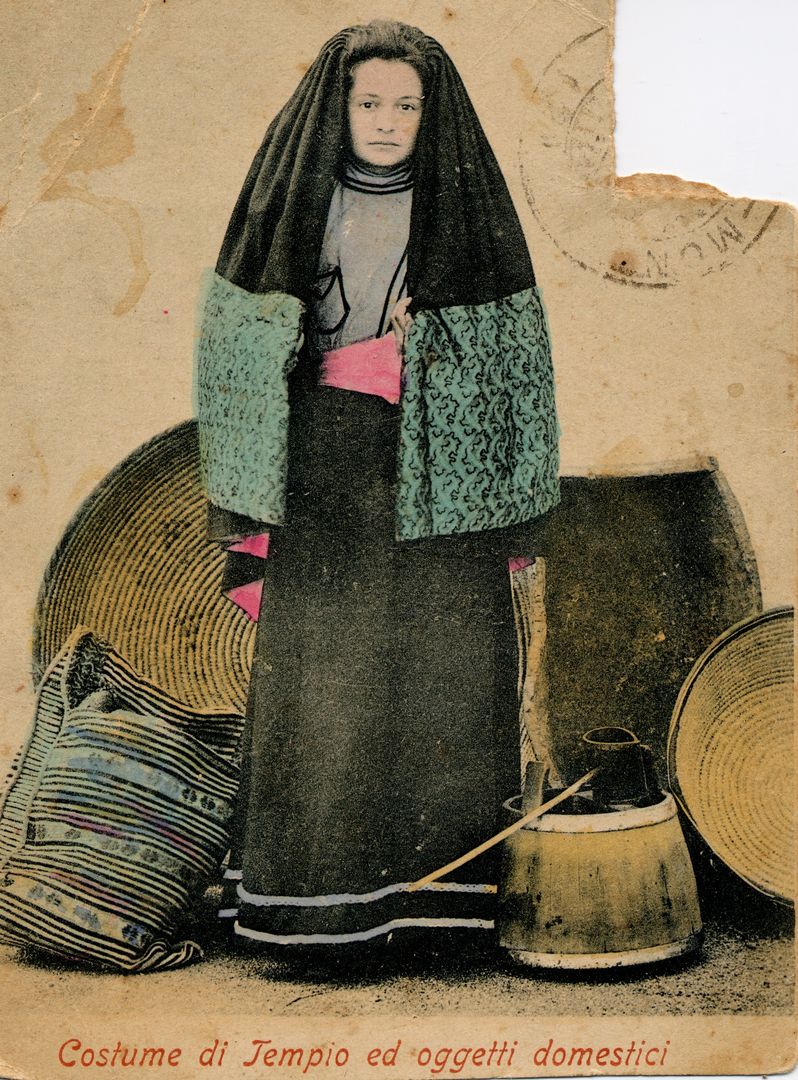

The under-petticoat, of cloth, is either of a bright colour, or dark with a bright-coloured border. Both of them are worn very full. The jacket is of scarlet, blue, or green velvet, fitting very tightly to the figure, the edges having a border of a different colour, and sometimes brocaded. The simple head-dress consists of a gaily-coloured kerchief wound round the head, and tied in knots before and behind.

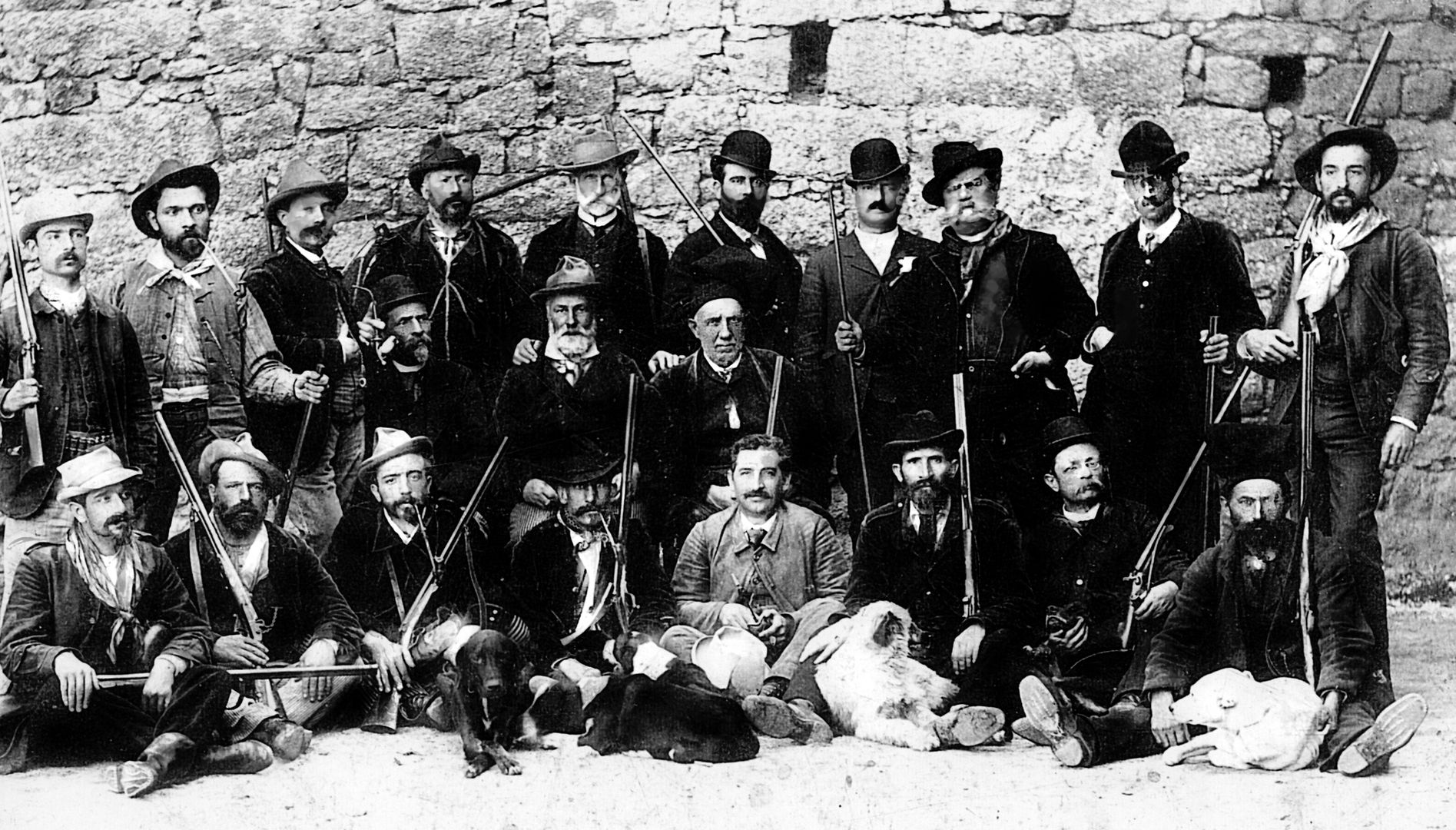

A singular conference it was, that meeting of ourselves, men of the north, with the wild chasseurs of the Gallura, between whom there was nothing in common but enthusiastic love of the field and the mountain.

The low vault of the Caffè de la Costituzione was lighted by a single lamp, by whose glimmerings we dimly discerned, amidst wreaths of tobacco-smoke, the grim features of the men with whom we had to do. They were honest enough, no doubt, according to Sarde notions of honour, and received us with great cordiality; but the consultation between themselves was carried on in a patois quite unintelligible, except that we gathered that there were some difficulties in the way.

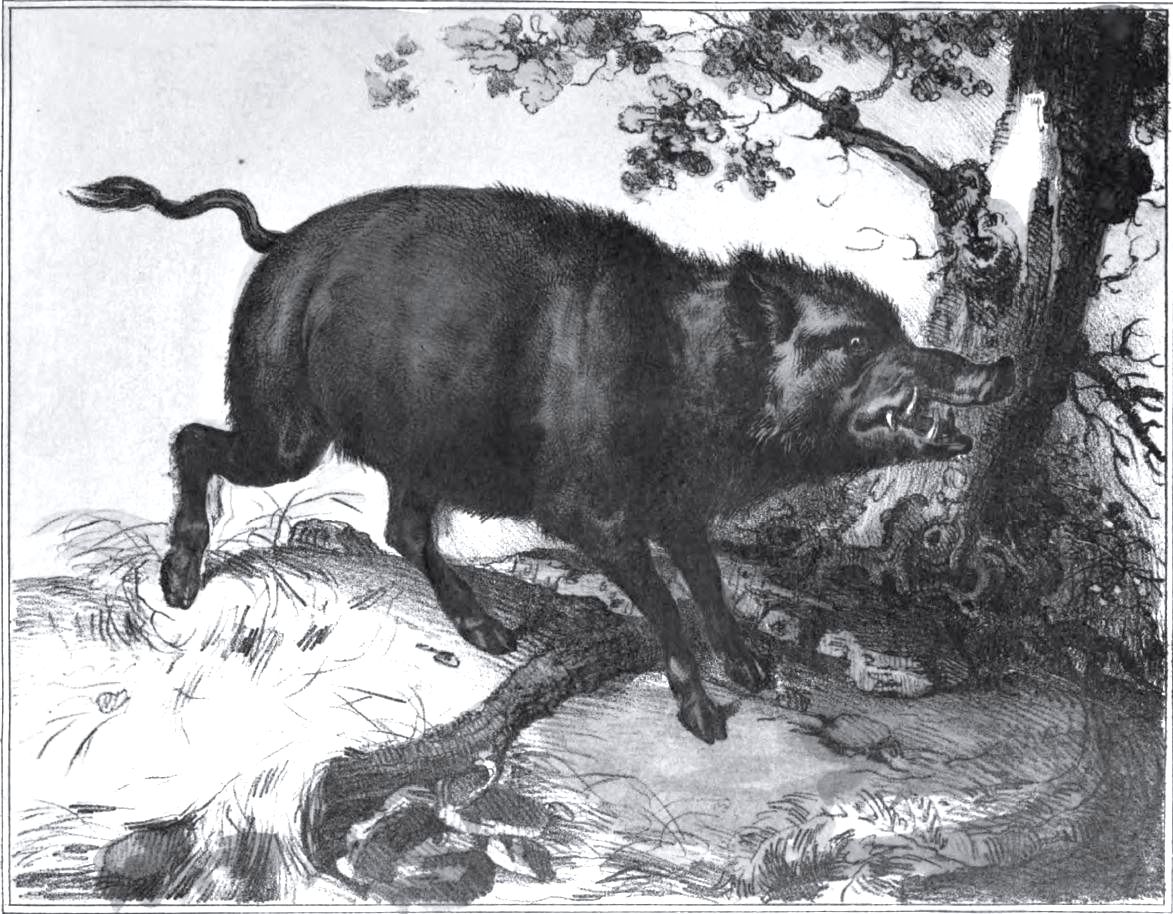

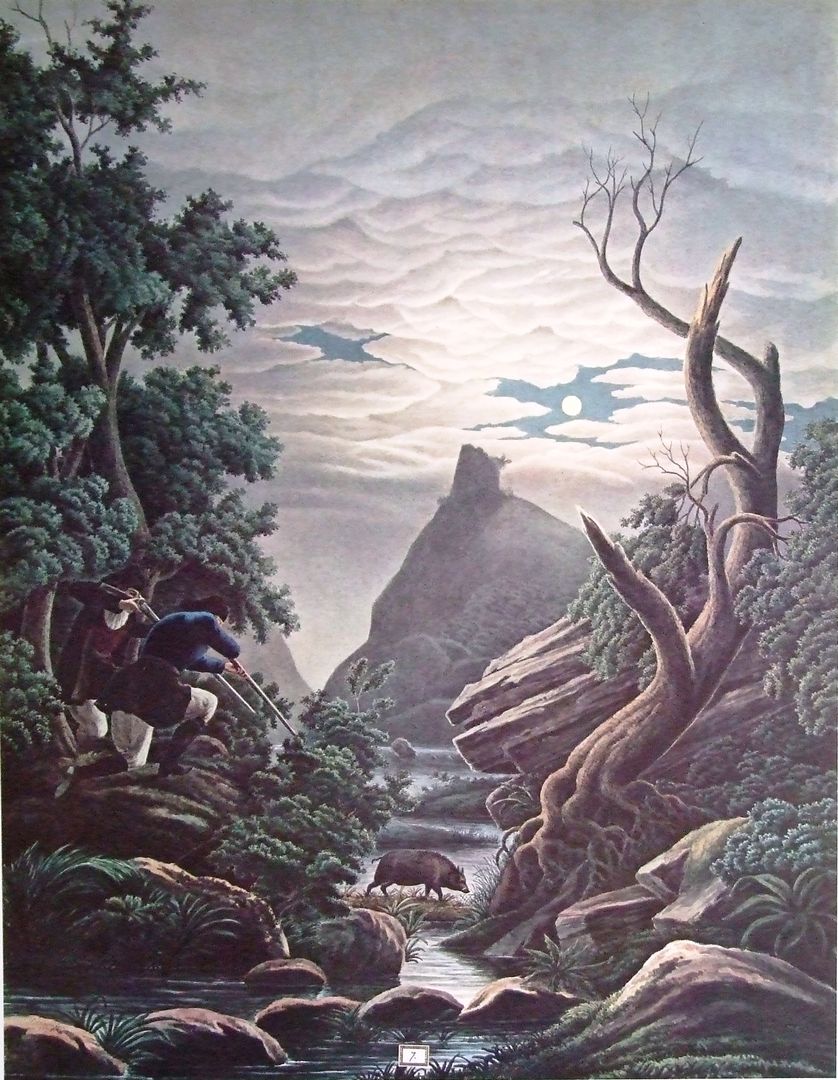

La caccia di cingale, a boar-hunt in Sardinia, requires a number of hunters, besides those who beat the woods to rouse the game; and, whether there were any feuds to be stifled, any jealousies to be allayed, which, with armed men in that state of society, might endanger the peace, the difficulties appeared serious. Whatever they were, our Barbiere di Seviglia, who, to use a familiar phrase, seemed up to everything, and conducted the treaty on our part, did not think proper to disclose them.

One thing, however, we soon learned, that the services of these men were not to be hired; their ruling passion for the chase and the national principle of hospitality were incentives enough to the proposed expedition. We were also informed that there were other parties to be consulted, and the meeting was adjourned to the following day.

We spent some pleasant hours there, finding among the members well-informed and intelligent persons. Politics were freely discussed, liberal opinions prevailing even to the degree of such ultra-liberalism as might have better suited the class of persons we met at the Caffè de la Costituzione, if politics are discussed there also. No doubt they are, the Tempiese, like the rest of the islanders, being a shrewd race, devotedly patriotic, and jealous of their independence.

My companion, who had the happy gift for a traveller of being almost omnivorous, used to laugh heartily at my vain attempts to extract something edible from the meagre carte offered by Madame. Her replies parrying my demands, and uttered with amazing volubility, in shrill tones and a patois almost unintelligible, invariably ended to this effect: – “Signore, my house is not a locanda, though I have opened my doors to accommodate you. “It was a species of hospitality that cost us dear. Madame’s airs of gentility, though very amusing, where of course treated with due respect. But what gave zest to my friend’s mirth, and, with the hopeless prospect of dinner, produced in me a slight irritation, sometimes, perhaps, ill concealed, was Madame Rosalie’s evolutions on these occasions.

I fancy, now, that I see her slight figure skipping into the room, dancing a jig round the table, never at rest, screeching all the while at the highest pitch of her voice, with every limb in motion, as if she had St. Vitus’s dance, or, as they say, went on wires. I can only compare the play of her limbs to that of one of those children’s puppets of which all the limbs ‒ head, legs, and arms ‒ are set in motion by pulling a string.

Accordingly, at an early hour, there was an unusual stir in the dull streets of Tempio, snapping of guns, trampling of horses, and barking of dogs.

On our joining the party at the rendezvous in front of the caffè, we found some twenty horsemen, carrying guns: rough and ready fellows, looking as if a dash into the forest, whether against hogs or gendarmes, would equally suit them. We were followed by a rabble on foot, attended by dogs of a variety of species, some of them strong and fierce.

Our irregular cavalry shaped their march in broken order towards a spur of the mountains, covered with dense thickets, at the foot of the Punta Balistreri, the highest point of the Limbara, After clearing the inclosures our track led us over the wide undulating plain already described, interspersed with scattered thickets, but with few signs of cultivation.

This handsome plant springs from a bunch of long fibrous bulbs, something like the Dahlia, throwing up straight stems two or three feet high, with numerous angular filiformed leaves and yellow flowers. It grows freely on all the wastes throughout the island. The root contains so large a portion of saccharine matter, and is so plentiful, that while we were in Sardinia a Frenchman was forming a company for distilling alcohol from it on an extensive scale. A distillery was to be established at Sassari, with moveable stills throughout the island, wherever the bulbs could be most easily procured. The projector gave us a sample-bottle of the alcohol, a strong and purely tasteless spirit. I heard afterwards that the speculation did not succeed.

The rest of our party soon afterwards struck up a valley parallel with the ridge, and facing the mountain side, which rose above it a vast amphitheatre of hanging woods, shelving and precipitous cliffs, rocks and pinnacles: so glorious a spectacle that it riveted my attention, and almost drew it off from the work before us.

It was my lot to be posted near the extreme right on a detached rock, slightly elevated, so as to command the ground, I could just distinguish my neighbours on either hand, “low down in the broom,” the valley being rather thickly covered with brakes of underwood. The instructions for my noviciate in boar-hunting were: not to quit my post, and to maintain strict silence; injunctions not likely to be disregarded, as a breach of the former might have exposed me to be winged, in mistake for a pig among the rustling bushes, considering that there were dead shots on either flank, with two or three balls in their barrels. As to the other word of order, silence, the injunction was needless, for the ear of my nearest neighbour could only have been reached by shouts which might scare the game, and prevent their breaking cover, and that I was not quite novice enough to risk. So I sat down on the rock, with my gun across my knees, watching the play of light and shade on the mountain sides as the clouds flitted round them. But this did not last long, for the line of vedettes could have been scarcely formed when the shouts of the party who had now gained the heights, and were beating the woods in face of our position, summoned the hunters in the valley beneath to be on the alert.

The interval of suspense and silence being now broken, the scene became very exciting. The dogs in the wood gave tongue, and the short and snapping bark was shortly followed by a full burst, which told that the game was on foot. Then, no doubt, every gun was at full cock, every eye intently watching the avenues in the thickets through which boar or deer, driven from the woods, might cross the valley. The shouts and cries sounded nearer and nearer, till at length a shot from the extreme left announced that some game had been marked as it broke cover. A dropping fire now extended at intervals along the line, as cingale or capreole burst from the thickets. Several fell to the guns of the party, some escaped; others, wounded, were pursued by the dogs to the rear of the position, with a rush of some of the hunters on their trail.

And so we entered the city in triumph. In the course of the evening the skin of the finest wild boar was sent to our quarters as a trophy of our share in the work of the day, with a joint of the meat. Madame Rosalie’s cuisine failed to do it justice; but, when well cooked, wild boar is excellent eating.

This mode of hunting, generally practised by the Sardes, resembles the battue of wolves and leopards at which I have assisted in South Africa, where the Boers, assembling in numbers, make an onslaught on the ravagers of their flocks; having the dens and thickets driven, and stationing themselves on the outskirts with their long roers to shoot down the vermin as they issue forth. Such meetings are jovial, and the sport is exciting, but not to be compared, I think, to deer-stalking or fox-hunting, to say nothing of a foray against lions and tigers.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

19th Century Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs (captions translated freely)

Michel Antony Shrapnel Biddulph, The Himbarra from Tempio [figure and original captions are in this book of Forester]

State Archive of Cagliari, “Church and convent of the nuns at Tempio”, 1821.

“Rifles made in Tempio”, IN Giuseppe Sotgiu, I fucili di Tempio, Tempio, Accademia Popolare Gallurese G. Gabriel, 2012.

Collection Luzzietti, “Men of Tempio”, ca 1795-1805, IN Francesco Alziator, La collezione Luzzietti: raccolta di costumi sardi della Biblioteca universitaria di Cagliari, De Luca 1963, Zonza 2007.

Giuseppe Cominotti, “Greetings from Tempio”, 1825, IN Francesco Alziator, La raccolta Cominotti: raccolta di costumi sardi della Biblioteca Universitaria di Cagliari, ed. De Luca 1963 e Zonza 1990.

Giuseppe Cominotti – Enrico Gonin [drawing], A.J. Lallemand [engraving], “Sardinian clothes in series – Tempio”, ca 1826-1839, IN Alberto Della Marmora, Voyage en Sardaigne, ou Description statistique, phisique… Atlas de la première partie, 1. ed. Paris, Delaforest 1826; 2. ed. Paris, Bertrand – Turin, Bocca,1839.

Nicola Benedetto Tiole, “Women of Tempio designed by my friend La Marmora”, 1819-1826, IN Album di costumi sardi riprodotti dal vero (1819-1826), saggi di Salvatore Naitza, Enrica Delitala, Luigi Piloni, Nuoro, Isre 1990.

Luciano Baldassarre, “Soap vendor woman of Tempio”, ca 1843, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Luciano Baldassarre, “Boar”, ca 1843, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna op. cit.

Simone Manca di Mores, “Boar hunting at night”, ca 1861-1880, IN Simone Manca di Mores, Raccolta di costumi sardi. Commenti alle tavole di Luigi Piloni e Antonangelo Liori, Cagliari, Della Torre, 1991.

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

Collection by Erennio Pedroni, Gianfranco Serafino, Vittorio Ruggero, Rotary, Mario Pirrigheddu.

Contemporary Photos

Matteo Aisoni – Flickr; Vittorio Ruggero – Flickr; Salvatore Lai – Flickr; Rudiger Anders – Flickr; Salvatore Solinas – Flickr.

Salvatore Pirisinu. IN Giovanni Gelsomino, La diga del Liscia. Storia e storie, Consorzio di bonifica della Gallura, 2006.

Michele Zucca CC BY-SA 4.0, wikimedia commons.