TEMPIO

by John Warre Tyndale

London 1849

Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street. Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty

in italian: ![]()

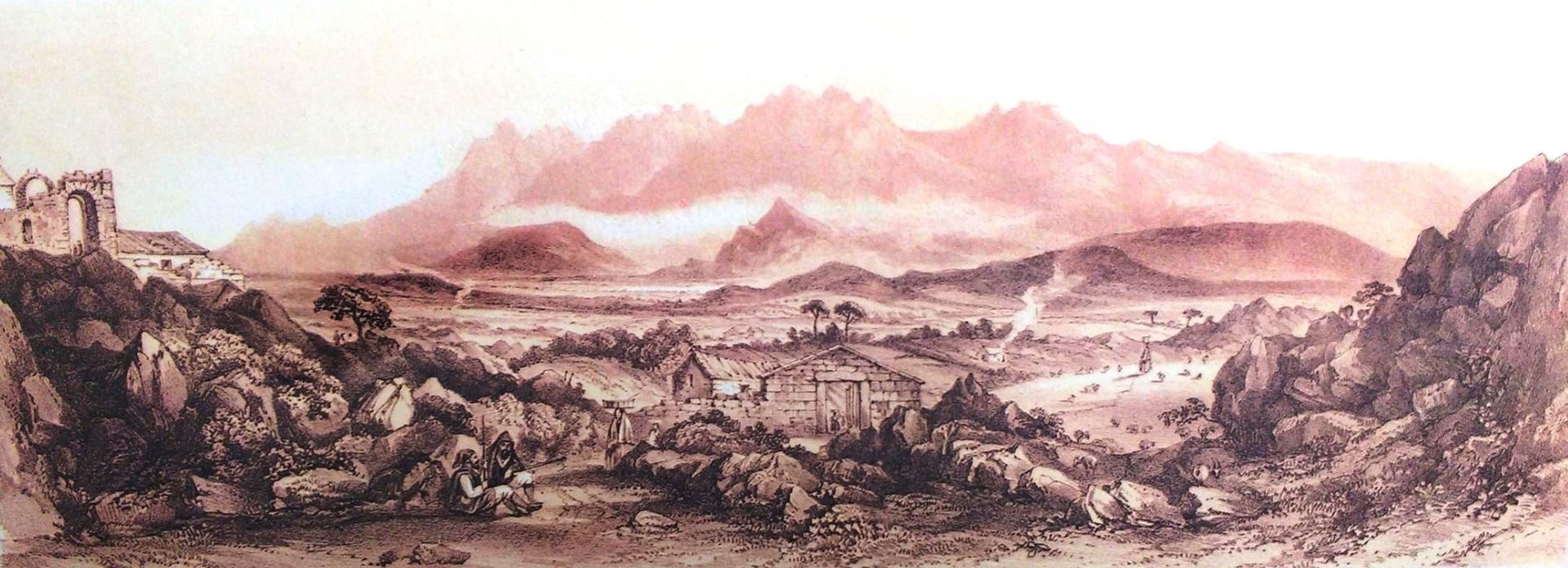

From the valley the road ascends through scenery of great beauty […].

The arrival of the king at Tempio was an opportunity of seeing the district and town under the most favorable circumstances. The assembling of the inhabitants of the different villages to join in a general fête and holiday, is a matter of unfortunately too frequent occurrence in Sardinia; but a royal visit drew them together with very different feelings.

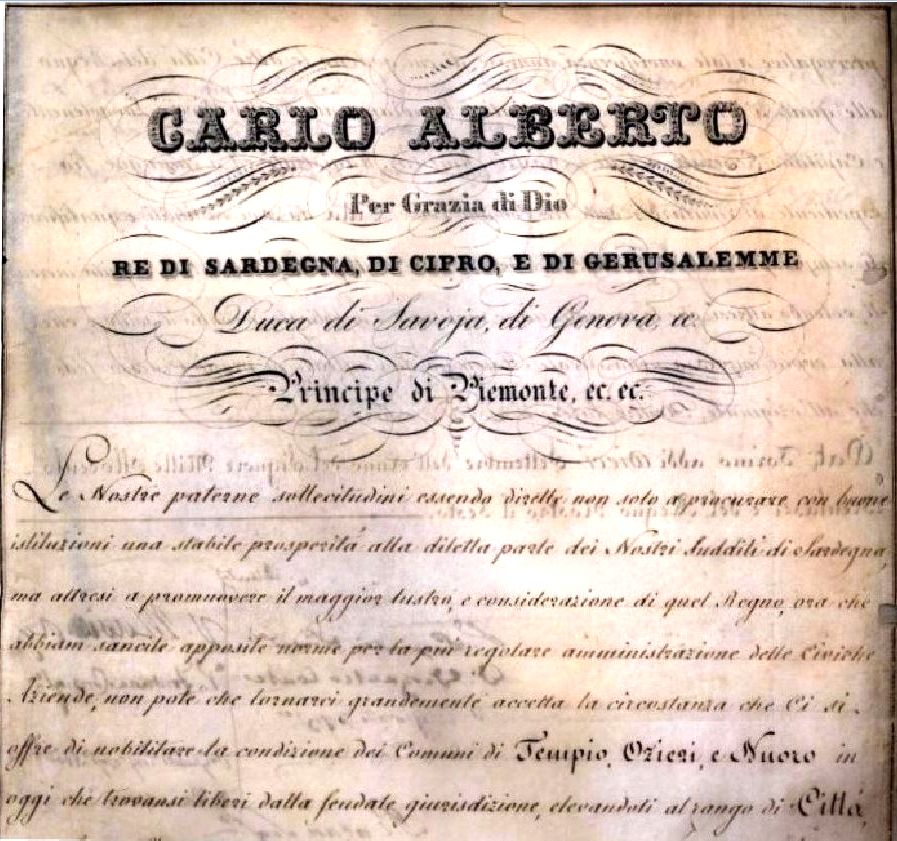

On the morning after my arrival, the whole town was busied in preparing for his Majesty’s reception; and by the kindness of the chiefs in authority, I was enabled to witness all the most important scenes. It was the first time that the Tempiese had ever beheld a monarch; Carlo Alberto had visited Tempio in 1829, when he was merely Principe di Savoia Carignano, and though that event was a strong shadow of royalty, and had initiated them a little into the sublime mysteries of the divine rights of kings, yet on the present occasion all eyes were strained to see a positive bona fide, real, living sovereign, and all mouths were trying to pronounce the words which they had never before essayed, “Viva il Re”.

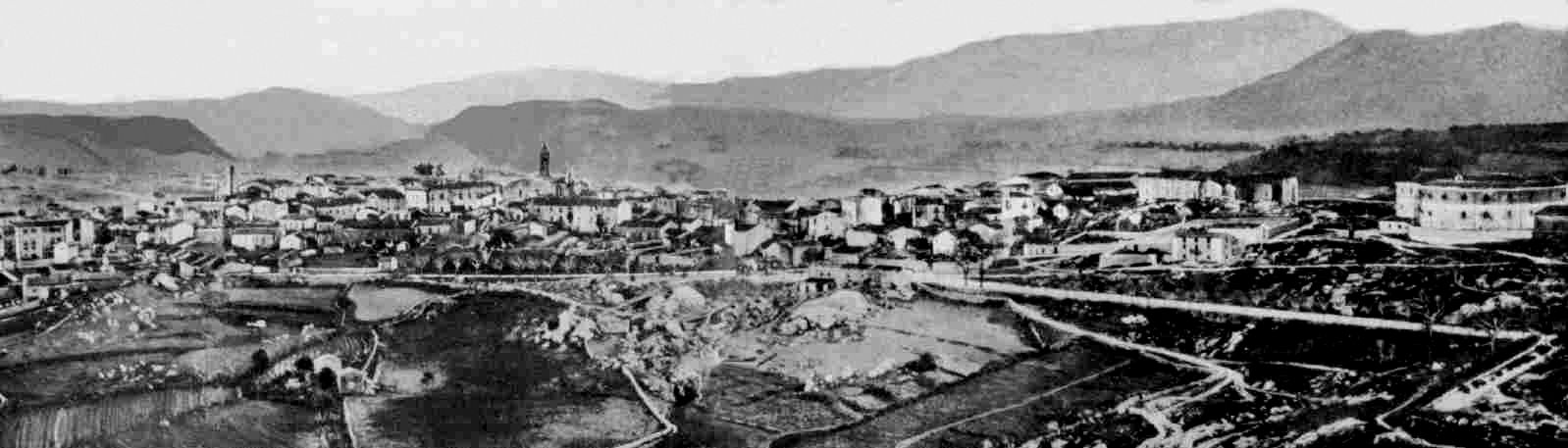

At the entrance of the principal part of the town, were two triumphal arched through which the king had to pass to his quarters at the bishop’s palace. These triumphal arches, made of a few stripes of wood, and covered with coarse linen, were painted to represent granite, and looked so well, that it gave the Tempiese an idea of building an arch of the real material to commemorate this royal visit. They even spoke of it as a probability, which in a Sarde’s mind is an enormous step towards the accomplishment of anything. Inscriptions were fixed up in various parts of the town, and crowds were beneath them trying to read them, or having them read to them.

In other parts, the rehearsal of musicians, the assembling of the militia, the union of the different flags of the villages of Gallura, the motley groups of politicians and priests holding forth on the royal advent; the costumes of the unsophisticated peasants from the various districts, the assumption of dandyism, the foppery of half-civilised employés, and the self-satisfactory step of the man of authority, formed unitedly a scene of amusement and interest. If all this confusion and bustle took place sub dio, one may easily imagine, by comparison, the state of the interior of every house. Each host had his rooms crowded with friends and relatives from the country; the preparation of the breakfasts, dinners, and suppers, called forth the domestic talents of the hostesses, and no less attention and assiduity were displayed in robing and adorning themselves and family.

The approach of the king, by the road which wound from the foot of the Limbara, was announced by the cannon of the town. By the expression, “the cannon”, is meant literally the definite article, and the substantive in the singular, for the artillery did not extend to the plural number. The salutes were therefore few and far between, and gave an idea of minute guns, or signals of distress, rather than a royal feu de joie. […]

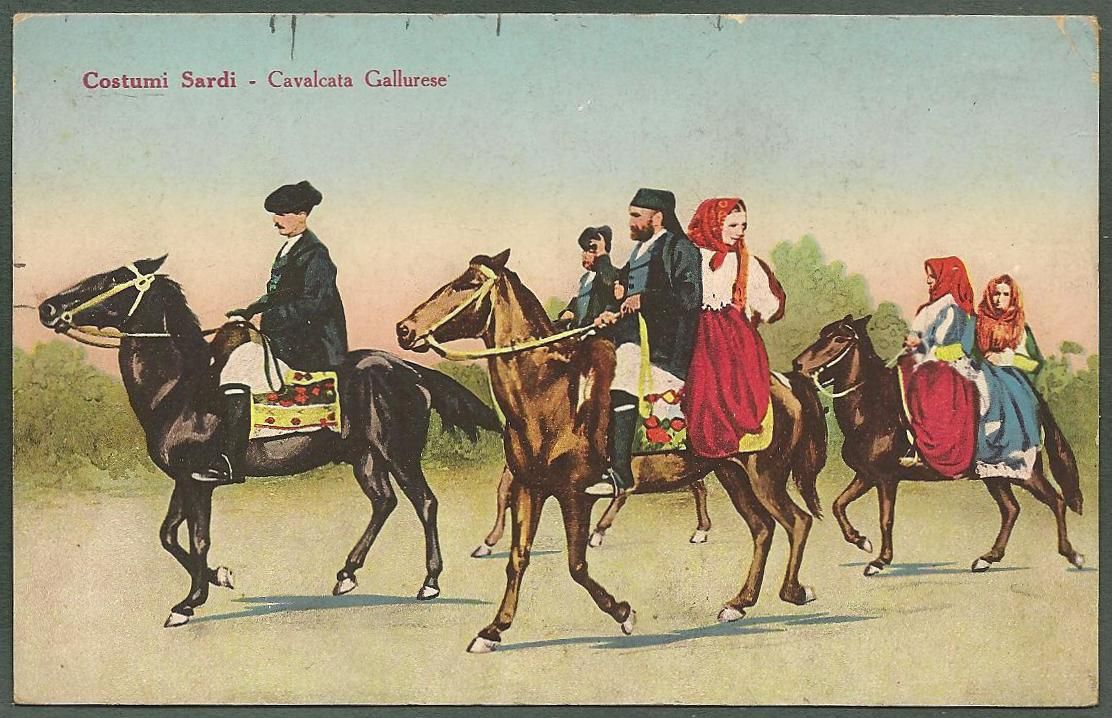

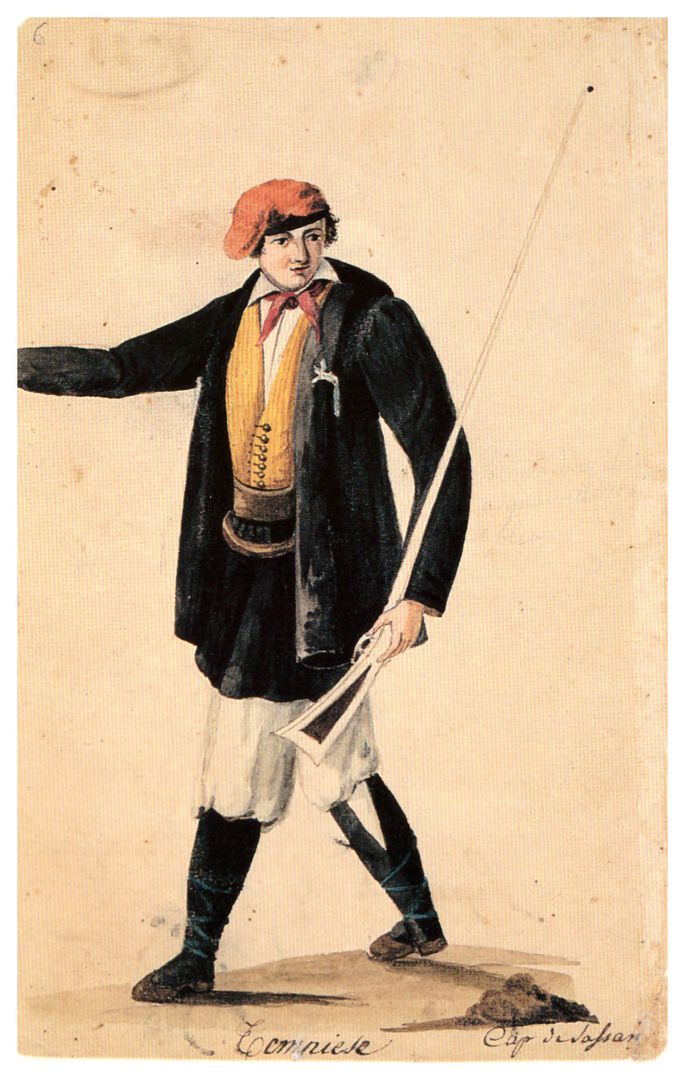

The procession was headed by the militia of Gallura, a body of about 200 men, dressed in their dark capote, long red cap, a double-breasted waistcoat of red velvet, and white mutande appearing between the braghi and the black gaiters. Carelessly seated on their meagre, but strong and active horses, their brightly-polished guns glistened in the beams of the setting sun, and their long and dark hair and beards gave the last touch to this Bedouin picture. Some light cavalry troops, the gens d’armerie of the country, followed; and immediately after them the king, with the Duke of Genoa and his suite.

On arriving at the gate of the town, the syndic, with the consiglieri and authorities, presented him the keys, reading to him, from a piece of paper, a set speech for the occasion.

In the evening, promenades, serenades, music, and illuminations drew the whole of the population from their homes, so that the streets were almost impassable; but there was no dancing, for it was Friday; singing is not a mortal sin, dancing is. […]

A large calico obelisk, with an inscription, was illuminated by lights placed inside; the windows were lined with transparent paper lanterns, having “Viva il Re” written on them; and attached to the trees were a variety of colored balloons, also transparent and lighted up. The combined reflection of these lights brightened the dark green foliage of the newly planted shrubs, and shewed out the variety and elegance of the costumes of the wandering multitude, the female portion of which appeared in more than their usual grace and loveliness, and completed the hallucination of this fairy scene.

For the women, it consists of a scarlet, blue, or green velvet jacket, fitting very tightly to the figure, the edges having a border of a different color, and sometimes brocaded. The sleeves were formerly worn open down the front seam, with silver buttons to close them when required; but this is not à-la-mode at present; and the camisola or outer doublet, of a similar character, is also laid aside by the peasantry. The petticoat, of a dark cloth, with a very bright colored border ten or twelve inches deep, is called Lu suncurinu; but when the material is fine or of silk, it acquires the title of La valdetta. The under-petticoat is also of cloth, but of a different color and quality; but both of them are very full, with countless plaitings at the waist, and, being worn outside the jacket, they consequently fall over the hips with great elegance.

The Tempiese, when she goes out, raises the suncurinu from behind, and brings it over the head with a peculiar knack and arrangement, which gives it a form and position somewhat resembling the Maltese hood; the bright broad border of the inner petticoat relieves the sober tint of the cloth; and the gay velvet-jacket peeps out with very effective brilliancy. No one seeing the suncurinu worn as a petticoat can imagine it can be so easily and elegantly metamorphosed into a hood.

The simple and elegant head-dress, su cenciu, consists of a gaily-colored silk kerchief tied into three knots triangularly, one of them fitting into the nape of the neck and the other two on the forehead. They have something of a rosette form, but so arranged as to shew the borders and fringe with a most graceful negligence, far superior to the general mode adopted in other parts of Europe where the handkerchief head-dress is in use. When in mourning, white fillets are worn, somewhat similar to those of nuns. […]

On Sunday the programme of the day was, Mass and Te Deum, Bersaglio and Graminatogjiu. The two former need hardly be mentioned, save that it was a fine field-day for the ecclesiastics, who went through their manoeuvres with great precision and order, and to the perfect satisfaction of their regal commander-in-chief of the church of Sardinia.

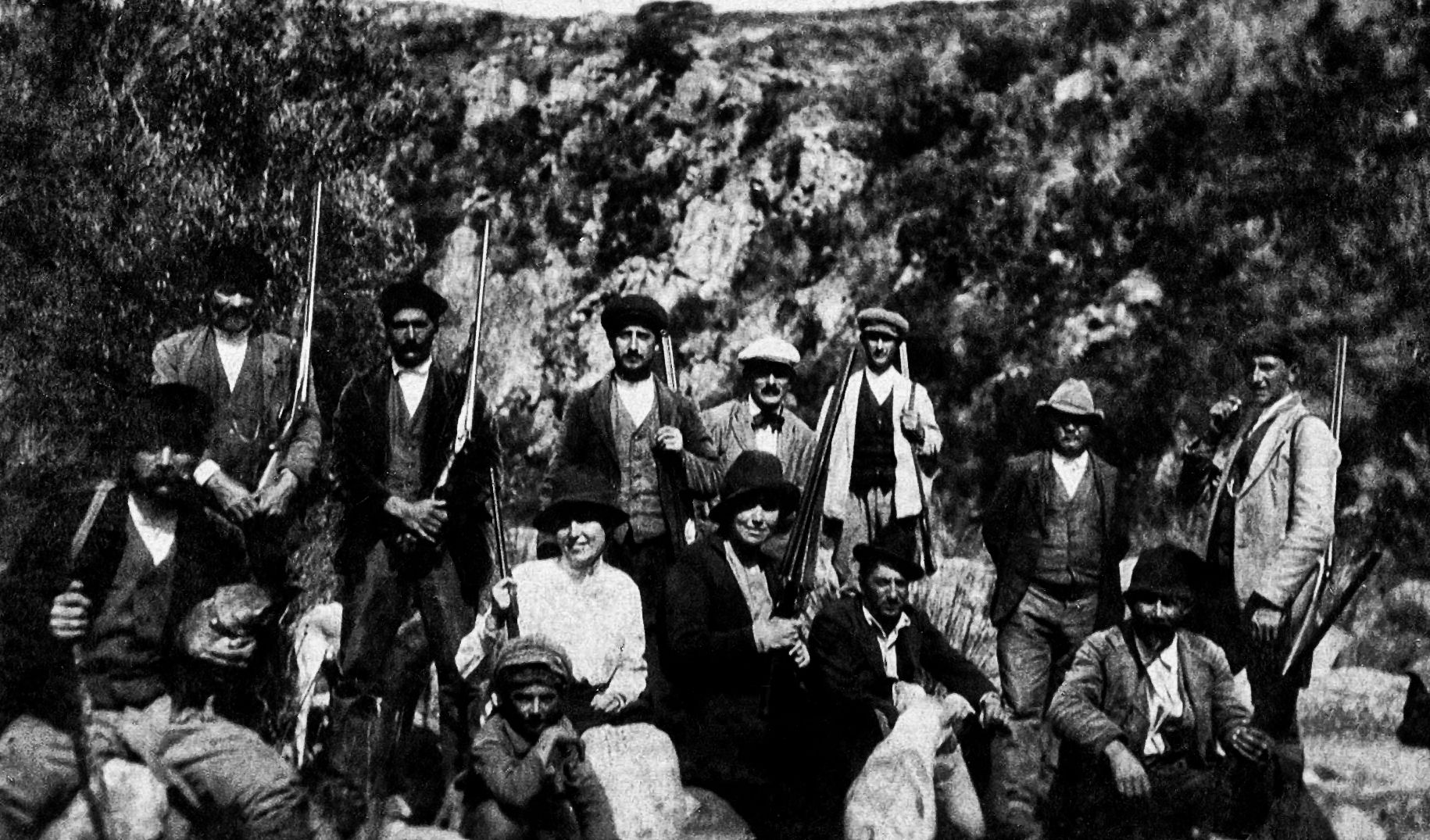

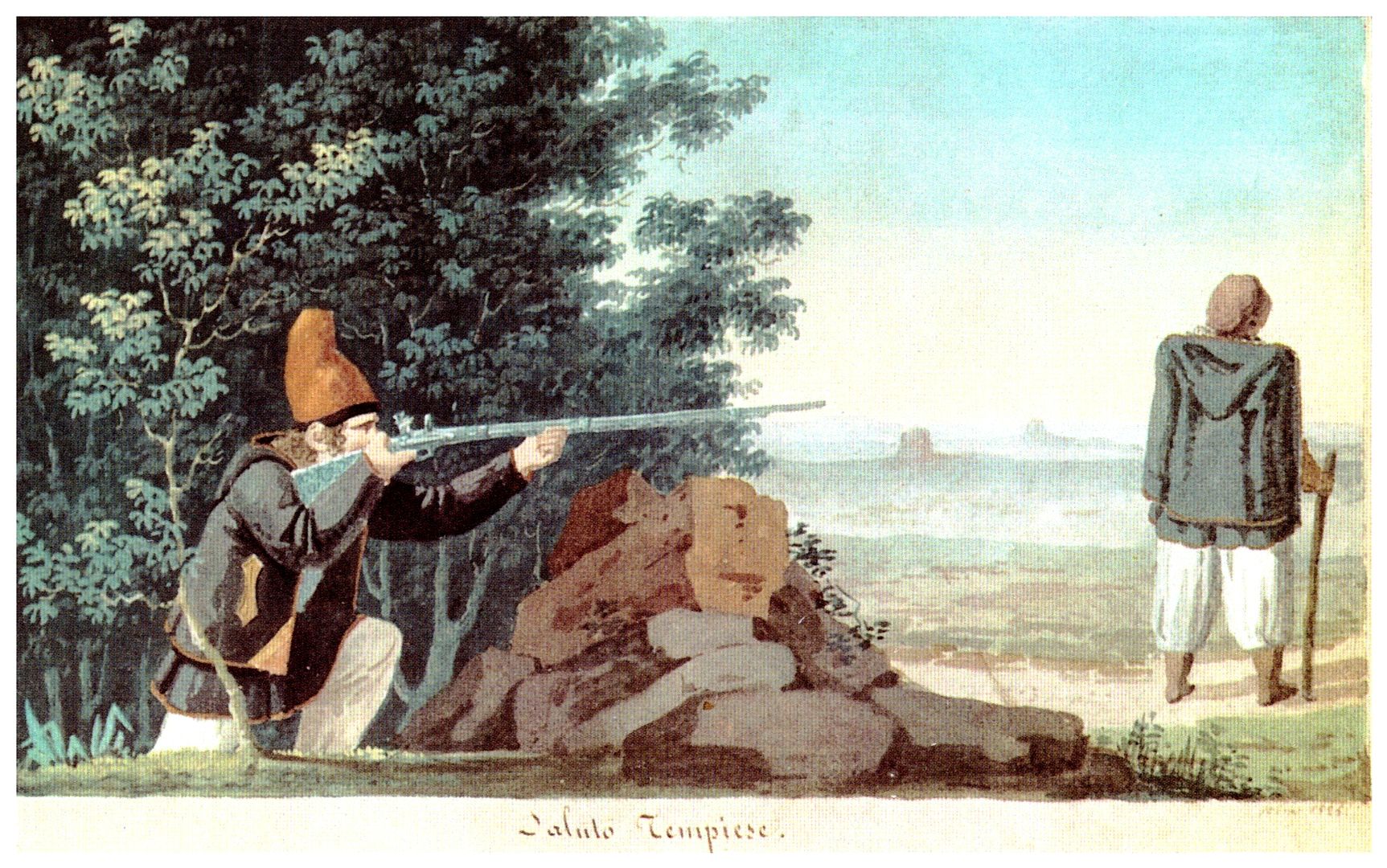

The Bersaglio, or shooting-match, took place outside the town on a level bit of road on the side of a hill commanding a fine view of the whole country towards the Monte Pulchiana. A platform and tent were erected for the king, and groups of people were scattered around to join in or witness this favorite national amusement.

The Bersaglio was a scene of great confusion and irregularity, and after three quarters of an hour’s continued firing, there still remained some 200 or 300 competitors, all anxious to try their skill and luck. A very small target was placed at about 150 yards off; and one in every three shots entered it. The centre of the bull’s eye having been hit, the king closed the scene, by giving an order to the fortunate marksman for a double barrelled percussion gun, with which, in all probability, he will never be able to take as good an aim as with that by which he won it.

The system in itself is good, uniting the “utile dulci” in the following successful manner.

B has a quantity of wool to be plucked, and she invites the rest of the consonants of the Tempiese alphabet to come to her house and do it. But she knows that consonants by themselves are mutes, and the male vowels belonging to them are therefore tacitly included in the invitation to make them pronounceable. C and D in their turn issue their “At Homes”. It is a treaty which is nominally for the reciprocity of service; but the secret articles belonging to it are, the admission of friends (who help them to do nothing), a small provision of flowers, bonbons, and ad libitum dancing when the wool is done; and as there is nothing in the treaty objectionable to the contracting parties, but, on the contrary, agreeable, the renewal of it is frequent.

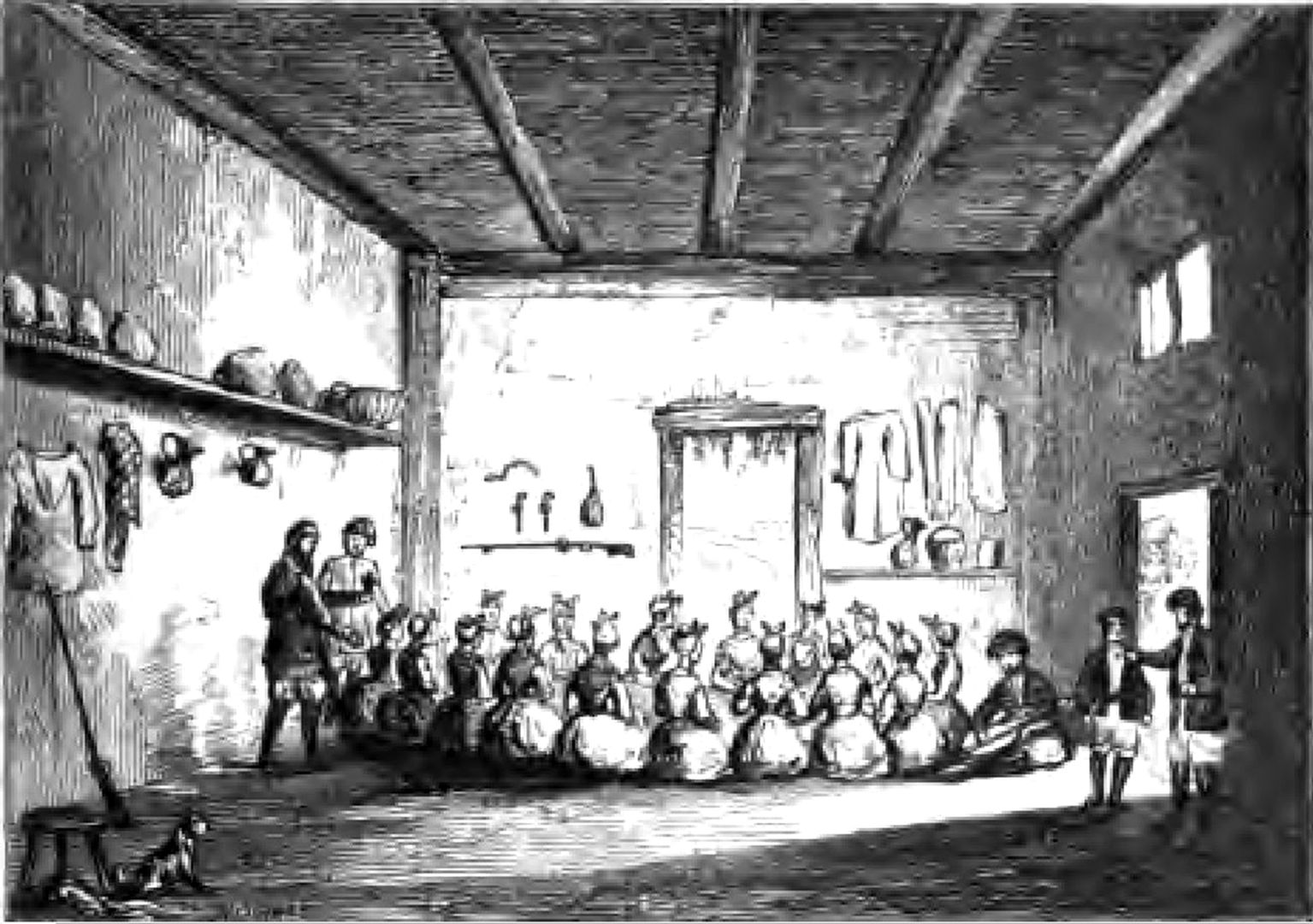

The Graminatogjiu, as prepared for the king, was very different to that in its natural and unregal character. His Majesty and the Duke of Genoa having taken their seats at the bottom of a room, with his suite around him, twenty-nine of the prettiest and cleverest damsels of Tempio were ushered in, and sat down in the middle of room, with a basket of flowers placed before them. Each of them received a small piece of wool, the plucking of which served them till the whole scene was finished. […]

The Principessa del Graminatogjiu having selected a bouquet from the vase, presented it to the King. Totally and happily ignorant of all form and ceremony, she, with sweet innocence and simplicity placed it in the hands of her sovereign, as though he had been a shepherd of her native hills, and he received it with a smile indicative of his appreciation of the gift, though no less of his amusement at the difference of a Turin and Tempio presentation. The next bouquet was, of course, presented to the Duke of Genoa, who accepted it in its proper and intended light — namely, an invitation to dance.

The music at length began, and the Duke of Genoa having been claimed by his partner, and the rest of us similarly drawn into the circle, the performance commenced; […] On the present occasion none entered more fully into the spirit of the ballo tondo than those who, though essentially Sarde by birth and feeling, have lived in the presence and influence of the court of Turin, without losing their national character and affections ; a fresh life seemed to be infused into them as they gradually warmed in the dance; and though “some sixty summers o’er”, they were roused into all the life and animation of thirty.

It was no less amusing on the other hand, to see the Viceroy, with other sedate authorities, for whom the dance had no national charm, figuring in the magic ring; an honor they would doubtless have dispensed with, but which it was politic to accept. After a few waltzes and quadrilles the party broke up, and thus terminated the royal Graminatogjiu.

The gentle zitelle were there, cross-legged on the floor, with a heap of wool apportioned to each of them. Their lovers were lolling and idling by their sides,

“The jest and youthful jollity, The quips and cranks and wanton wiles, Nods and becks and wreathed smiles”, passed with general animation and hilarity, almost drowning the sharp notes of the guitar.

The costumes had none of the extreme formality or wonderful cleanliness in “which they were exhibited to regal eyes”. Perfectly at ease in their daily but elegant dress, they worked at the wool, the bundles of which decreased or remained according to their industry or idleness; or, in equivalent terms, according to the absence or presence of the cavalieri. But the laugh and conversation were suddenly checked by a voice from one of the bystanders, who commenced his song, accompanied by the never-failing guitar. Frequently the “bene, bene”, came from many a voice, indicating the excellence of the composition; and the tale of love being finished, the hero presented the heroine with the flower he had been holding, as the ostensible subject of his song. She placed it in her bosom with an air of triumph, and, after a slight pause, asked one of her friends to answer the verses for her. Having placed himself by her side, he ascertained the true thermometrical state of her heart, and consequent nature of the response that he might give; and being thus armed with her tender weapons, he dictated to her, line by line, the answer, which she accordingly sang. Each line was written down and translated to me as it came forth, and as such it will be presented. Several other Parnassus knights subsequently entered the lists of this poetical tournament, in which love was naturally the cause of each encounter, and produced various “woeful ballads” to their “mistress’s eyebrow”, some of considerable merit. The manual part of the Graminatogjiu was now nearly drawing to a close, but it was quite evident that their ideas had been more wool-gathering than their hands wool-plucking.

The last scene of the first act was finished most unceremoniously, and the first scene of the last act began with the introduction of bonbons and rosolio; and such is their partiality for the former that an ounce will repay 100 pounds of wool; nor are they diffident in a little contraband trade, for the smuggling them into their pockets was an important part of the scene.

The sound of the music of the ballo tondo raised immediately all the maidens from their cross-legged postures, and summoned them all in its service; and it was kept up with a spirit and continuance which was a certain remedy for two hours and a half’s cross-leggedness.

One of the most amusing parts of the entertainment was the observance of the features of the different parties, which formed so clear an index to their feelings. The happiness and vanity of those who had received a flower and “blushed at the praise of their own loveliness” being sung aloud; the interest and attention excited in others, though not the favored objects of the youthful poets; the occasional bitter and forced smile of half envy, half rivalry; the hasty but searching glance occasionally thrown round the room in search of their cavalieri, were more or less depicted on the countenances of the fair conclave. On the other hand, the anxiety of many a swain to sing his mistress’s charms, with the silent ambition of gaining additional favor in her eyes by a public exhibition of his talents; and the appreciation or depreciation of each other’s poetical powers, either in rivalry or the spirit of criticism were equally “written on their brows”. The only countenance in the whole group which seemed to be moved by thoughts of an unromantic and substantial nature, was that of the owner of the wool, who betrayed her ideas of the infinite superiority of a staple commodity when placed in comparison with poetical sentiment and dancing.

In the Improvisatori and Improvisatrici (for both sexes are thus endowed) one sees the idea “Poeta nascitur” curiously confirmed, for the system of education which exists, instead of extending and improving, seems rather to repress and nullify the imaginative powers. The Tempiese, from their infancy, are accustomed to “lisp in numbers and to breathe in song”; yet few have risen to any general eminence, or been recognised as poets on Terra ferma. […]

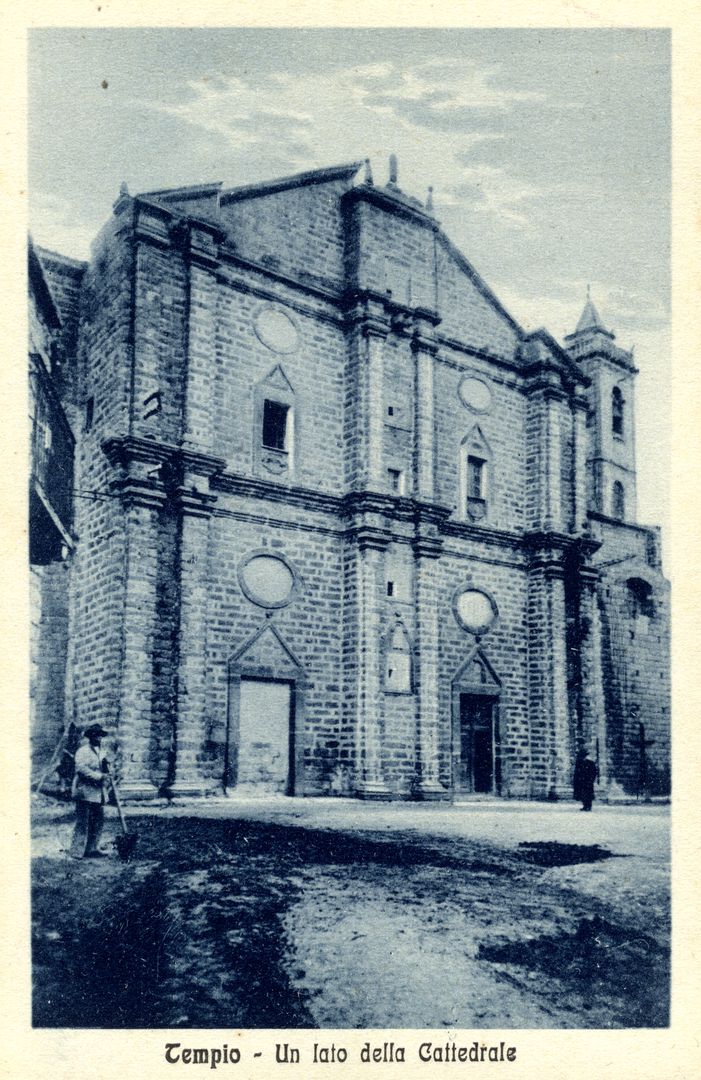

The Cathedral is a mixture of styles, some evidently of early date; but in the various repairs and alterations, the modern Italian predominates. It is large and lofty, and the general effect good; and having been lately whitewashed in honor of the King’s visit, was wonder-fully clean. The high altar, with a handsome balustrade of coloured marbles, the well carved oak choir, and a new marble pulpit, massive, but somewhat heavy, are the principal objects. The pictures are few, and have little merit.

In 1560, it was merely a collegiate church, dedicated to St. Peter by Gregory XV; and several applications were made without success to the Holy See to transfer the Bishopric of Civita, (the services of which, virtually, were performed at the Church of St. Simplicius at Terra Nova,) to Tempio. No change, however, took place till 1839, when Gregory XVI raised the church to the rank of a cathedral (independently of that of Ampurias and Civita), with a dean, twelve canons, to whom another has lately been added, to superintend the musical department, and eighteen “benefiziati”, corresponding nearly to our minor canons.

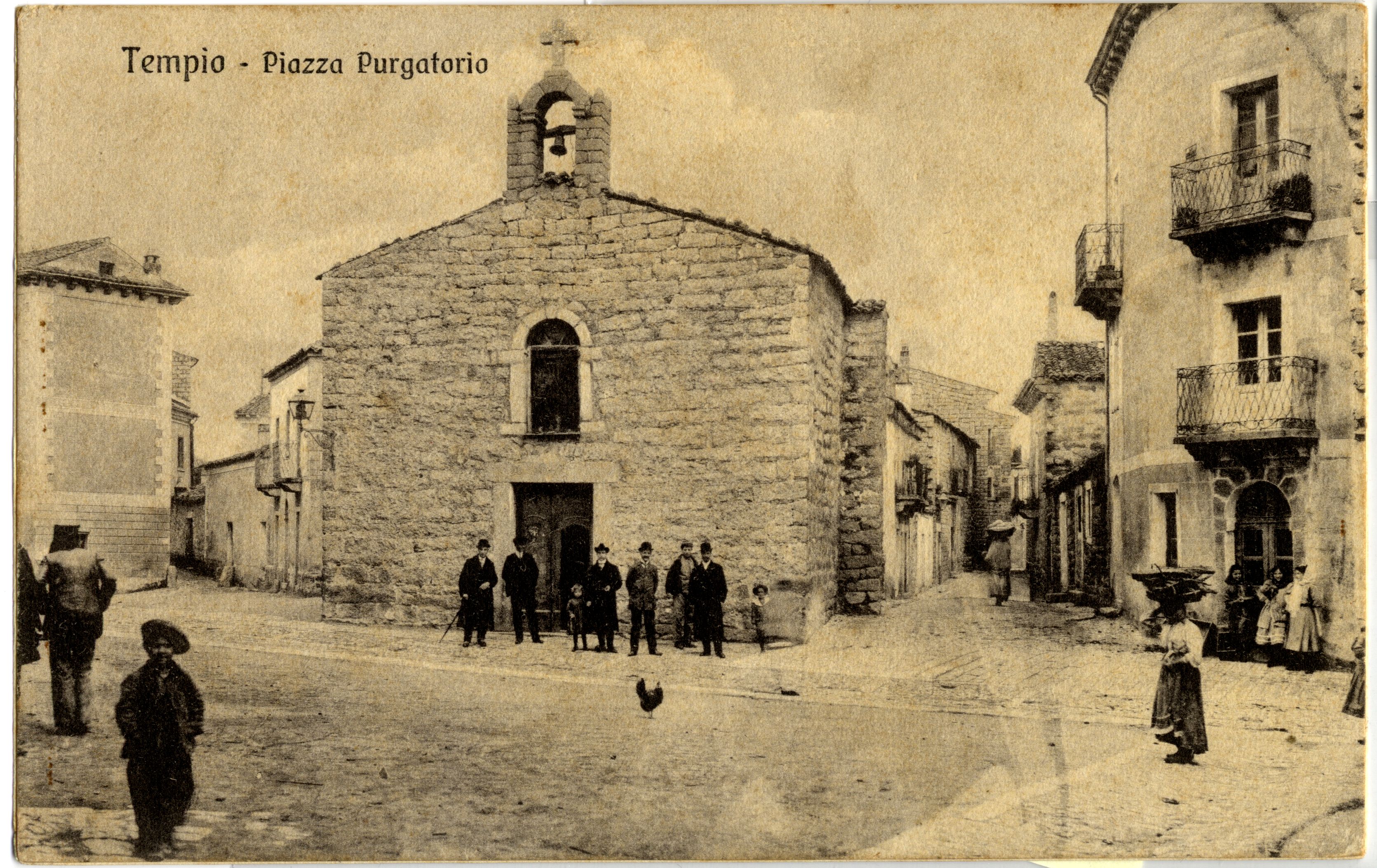

It was built and dedicated to the “anime del Purgatorio”, by Don Giacomo Misorro, an extensive land-proprietor in the Pulchiana district, over which he exercised an unbounded liberty and licence, and followed up his marauding expeditions with a cruelty and vendetta which made him the dread of the whole neighbourhood. A lawless band of outcasts served him faithfully in all his iniquities; one of which occurred on the identical spot where this church now stands.

A dispute having arisen between him and a rival neighbour, acts of offence and retaliation took place, but no opportunity occurred for a decisive blow till Don Giacomo ascertained that twenty of his adversary’s party had started for Tempio on a mission, dangerous in its results to himself. In the course of a few hours he collected a body of his own followers, and at night overtook them in one of the defiles where they had halted. The onset was sudden and short; eighteen were slain, and of the two that escaped one was retaken and murdered, and the other conveyed to the house of Don Giacomo. But the mere slaughter of them was not sufficient; he returned in the morning to this human abattoir, and gloating over his mangled victims, leisurely smoked his cigar, and insultingly turned them over and kicked them about. In perfect confidence that law and justice could not touch him he returned home; but in the course of a few days imagining some danger and treachery in a negotiation he had entered into with the friends of his prisoner, relative to a ransom, he deliberately told him his suspicions, and taking out a pistol shot him through the heart.

But impunity power, and wealth, availed not, against conscience. How dear are its pangs, but how cheap are its indulgences, penitences, alms, oblations, and vows! Don Giacomo went to Rome and obtained absolution for this and the numberless other enormities weighing on his guilty soul. The legends of Gallura do not state the compromise he entered into there, but he returned to Tempio, and built the church “Del Purgatorio” on the precise spot where he had committed his wholesale massacre. Under the auspices and thraldom of the priesthood he spent the remainder of his days in masses and confessions; and if they can be considered a virtue, he died like the Corsair, “Linked with one virtue and a thousand crimes”.

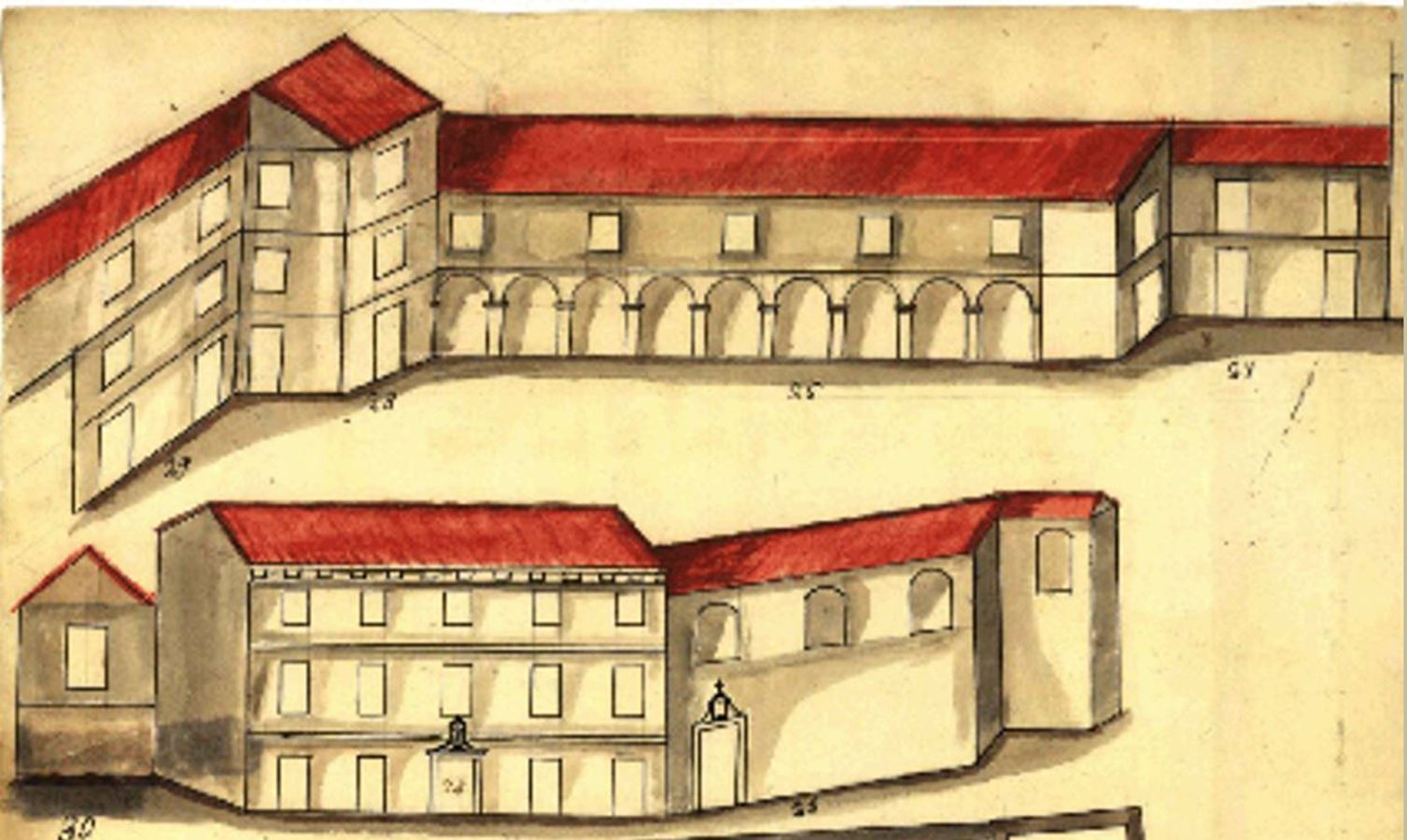

Monastic institutions have not thriven in Tempio. In 1635, a Tempiese bequeathed a sum of money to found a Capucin monastery, but it was applied to other purposes; and in 1690, a Capucin nunnery was established, but the fail recluses subsequently quarrelled among themselves, and if the scandal be true, their philanthropy was of so tender a nature, that eventually the convent was suppressed.

One cannot presume to say whether it was priestly, platonic sentiment, or natural honest affection, an unworldly anxiety to have her wealth settled on their institution, or to prevent its felling into worldly hands; but it is sufficient that another lover, who, jure parentis, was betrothed, and Jure suo much attached to her, was determined to exemplify, by practical experience, to the Jesuits, that which Loyola had theoretically laid down, that “might is right, and right is might”. It was late in the evening when our lay hero knocked at the door of the monastery, and having obtained admission, after a short time, he, on some pretext, withdrew, saying that he would return immediately. He did so, but accompanied by nearly 200 men, who immediately seized the Jesuits; and while part of the armed force carried them off, the rest stayed and destroyed the whole of the interior of the building, leaving only the church of St. Giuseppe.

One of my friends in Sardinia has twice received this unmitigated hint. In one case he knew the party who had thrown the ball, and with a consciousness of not having aggrieved the man, but that his hostility arose from a misunderstanding and belief in some false reports, he boldly hunted out his adversary, explained matters, and they immediately were reconciled; and, in a subsequent conversation, he explained the way he intended to have shot my friend. They now live on very good terms, neither of them feeling the slightest inclination to annoy each other, and still less daring to complain of each other to any authority. It is stated that this custom was originally recommended, and at last enforced by the priests, who not having sufficient influence or power to prevent these murders, endeavored to mingle a little charity and honor in them; an evidence that confessions and absolutions availed more than law and justice.

As a population, the Tempiese are strong, athletic, and hardy; their constitution is strengthened by their occupations; a spirit of activity (one of the few exceptions to the general apathetic indolence of the Sardes) induces them to migrate so that they are to be found in almost all the principal towns in the island; and from their industry they are called “Gli Ebrei de Sardegna”; but as they are honest, they may feel more complimented in being stigmatised as “Ebreo della Gallura”, than if they were likened to a lazzarono of Cagliari. In many respects they are like the Galliegos of Spain, whose honesty and high-mindedness, though engaged in laborious and sometimes menial occupations, have reflected such credit on the province to which they belong.

A dash of the pen of the King of Sardinia is a much easier operation than protracted debates and ponderous parliamentary reports on municipal corporations in other countries; but it is very doubtful if the royal grant has not been, by its centralising effects, more injurious than advantageous. It was, however, thankfully received, judging, at least, from the numberless inscriptions in Latin and Italian relative to it, placed in all parts of the town on the arrival of His Majesty, and which quite apotheosised him for the supposed blessing.

A handsome uniform for the Syndic is perhaps the king’s latent meaning of municipality; […] The few archives existing in the town are mostly Papal ordinances, and others relative to church matters, the greater part of modern date and of little interest on general points of history.

My time allowed me to make but a slight acquaintance with the Limbara monarch ‒ to have accepted his “sub Jove frigid” hospitality, and have known all the minor branches of his family ‒, his snows, his crags and precipices, his fountains and his glens.

This magnificent granitic mountain decreases on the north side by successive minor ranges till it reaches the coast; but on the south is very precipitous, and rises suddenly out of the plain.

A small waterfall of about thirty feet called “Il Pisciaroni”, is the weathergauge of the district, for, on a still, quiet day, the sound of it may be heard at Tempio; and when it becomes loud, is the harbinger of approaching bad weather.

Another fountain, called Franzoni, is said to be so cold at certain seasons that it breaks the glass into which it is poured, and that wine will lose its colour if immersed in it for a few hours.

Many were the expeditions against each other, and the noblesse having failed in many of their minor encounters, determined on one grand effort, to drive their enemies out of their haunts to the summit of the mountain, and there exterminate them. Having scoured the glens and gorges in the lower part of the Limbara, they were ascending a narrow and precipitous defile in the silence of a dark night, when a voice suddenly broke on their ears, ‒ “Eccomi”‒, Here am I. It was the shout of the father who had saved his daughter’s honor at the risk of his own life; and from the ambush in which he and his companions had concealed themselves, a galling and destructive fire was instantaneously poured on their adversaries. They all fell, the pass was covered with their bodies; and so great was the slaughter that almost every noble family in Tempio had to mourn the loss of one of their relations.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

19th Century Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs (captions translated freely)

Nicola Benedetto Tiole, “Man of Tempio”, ca 1819-1826, IN Nicola Tiole, Album di costumi sardi riprodotti dal vero (1819-1826), saggi di Salvatore Naitza, Enrica Delitala, Luigi Piloni, Nuoro, Isre 1990.

Giuseppe Cominotti “Militia in service” [snippet], ca 1826-1839, IN Giuseppe Cominotti and Enrico Gonin [drawing], A.J. Lallemand [engraving], IN Alberto Della Marmora, Voyage en Sardaigne, ou Description statistique, phisique… Atlas de la première partie, 1. ed. Paris, Delaforest 1826; 2. ed. Paris, Bertrand – Turin, Bocca,1839.

Giovanni Marghinotti, “King Carlo Alberto”, 1842, IN Municipal palace of Tempio Pausania, photo by Franco Pampiro.

Aldo Fornoni, Tempio, ca 1951, IN Costumi popolari italiani, Milano, Gorlich, 3 v., 1951-1958 (1: Italia meridionale, Sicilia, Sardegna, 1951) [clear reproduction of the soap vendor woman of Tempio, of A. Pittaluga – 1828, then also reproduced by L. Baldassarre – 1841].

Alessio Pittaluga, “Shepherdess from Gallura”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes, par A.[lessio] Pittaluga, Paris, chez Marino; Firenze, Antonio Campani, 1826 (rist. Carlo Delfino 2012).

Philippine de La Marmora, [Woman from the] “District of Tempio”, 1860, op. cit.

Giuseppe Cominotti and Enrico Gonin [drawing], A.J. Lallemand [engraving], “Sardinian clothes in series – Tempio”, IN Alberto Della Marmora, op.cit.

Nicola Benedetto Tiole, “Women of Tempio seen from behind”, ca 1819-1826, op. cit.

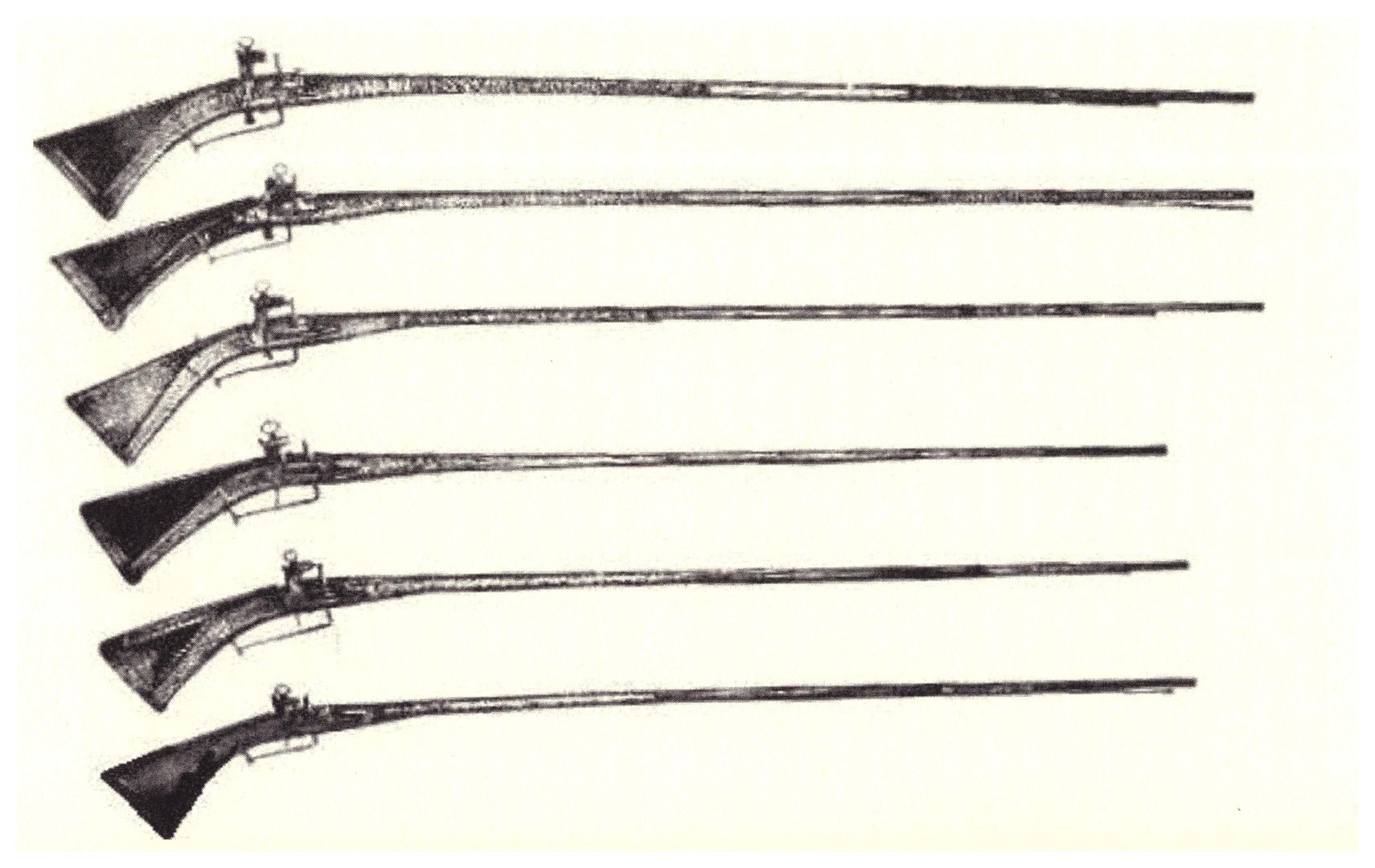

“Rifles from Tempio”, IN Giuseppe Sotgiu, I fucili di Tempio, Tempio, Accademia Popolare Gallurese G. Gabriel, 2012.

Lorenzo Pedrone, “Shepherd from Gallura”, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Philippine de La Marmora, “Woman of Tempio”, 1860, op. cit.

Giuseppe Cominotti and Enrico Gonin [disegno], A.J. Lallemand [incisione], Graminatorgiu, 1826, IN La Marmora, op. cit.

Giuseppe Cominotti and Enrico Gonin [drawing], A.J. Lallemand [engraving], “Sardinian dance – area of Sassari”, ca 1826, IN Alberto Della Marmora, op.cit.

John William Cook, A graminatorgiu at Tempio, ca 1843-1849, IN this book.

Luciano Baldassarre, “Round dance”, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna op. cit.

Bartolomeo Pinelli, “Costumes of Tempio”, ca 1828, IN Raccolta di costumi italiani i più interessanti disegnati ed incisi da Bartolomeo Pinelli nell’anno 1828.

State Archive of Cagliari, “Church and convent of the nuns”, 1821.

Giuseppe Cominotti, “Greetings from Tempio”, 1825, IN Francesco Alziator, La raccolta Cominotti cit.

Jean Baptiste Barla, “Wealthy man from Tempio”, 1841 (coll. Angelino Mereu): https://amerblog.wordpress.com

Jean Baptiste Barla, “Wayfarer of Tempio”, 1841 (coll. Angelino Mereu): https://amerblog.wordpress.com

Agostino Verani, “Men of Tempio”, ca 1806-1815, IN Scoperta della Sardegna. Antologia di testi e autori italiani e stranieri, a cura e con introduzione di Giuseppe Dessì, Milano, Il Polifilo, 1967, p. 128.

Alessio Pittaluga, Country man from Tempio, ca. 1826, op. cit.

Agostino Verani, “Women of Tempio”, ca 1806-1815, IN Scoperta della Sardegna. op. cit.

State Archive of Cagliari, “Grant of the city title to Tempio”, 1836.

Carlo Brundo, Picco Balistreri. Racconto storico del sec. XVII, Cagliari, Timon, 1875, rist. Istituto Giulio Cossu, Tempio, 2012

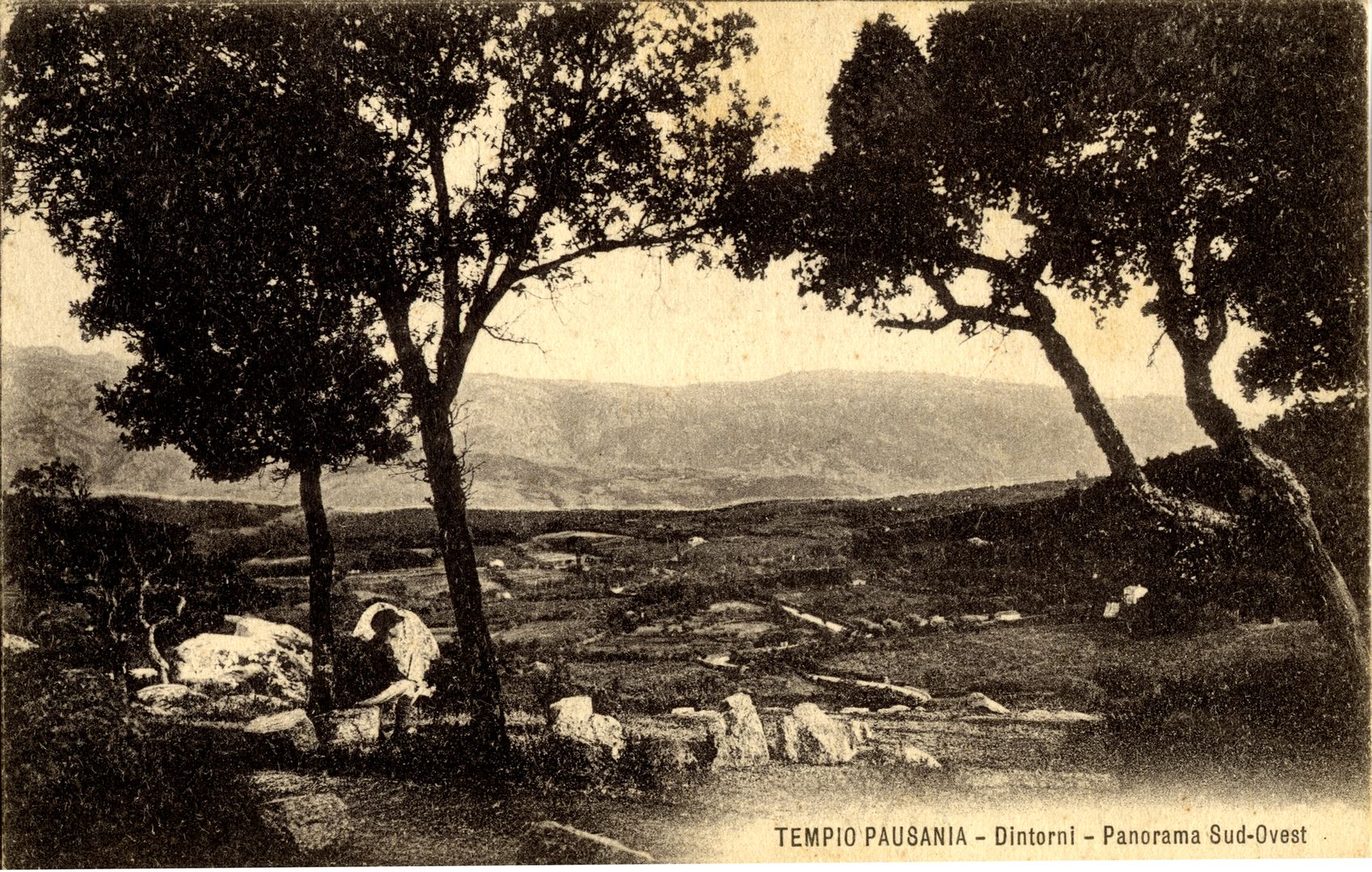

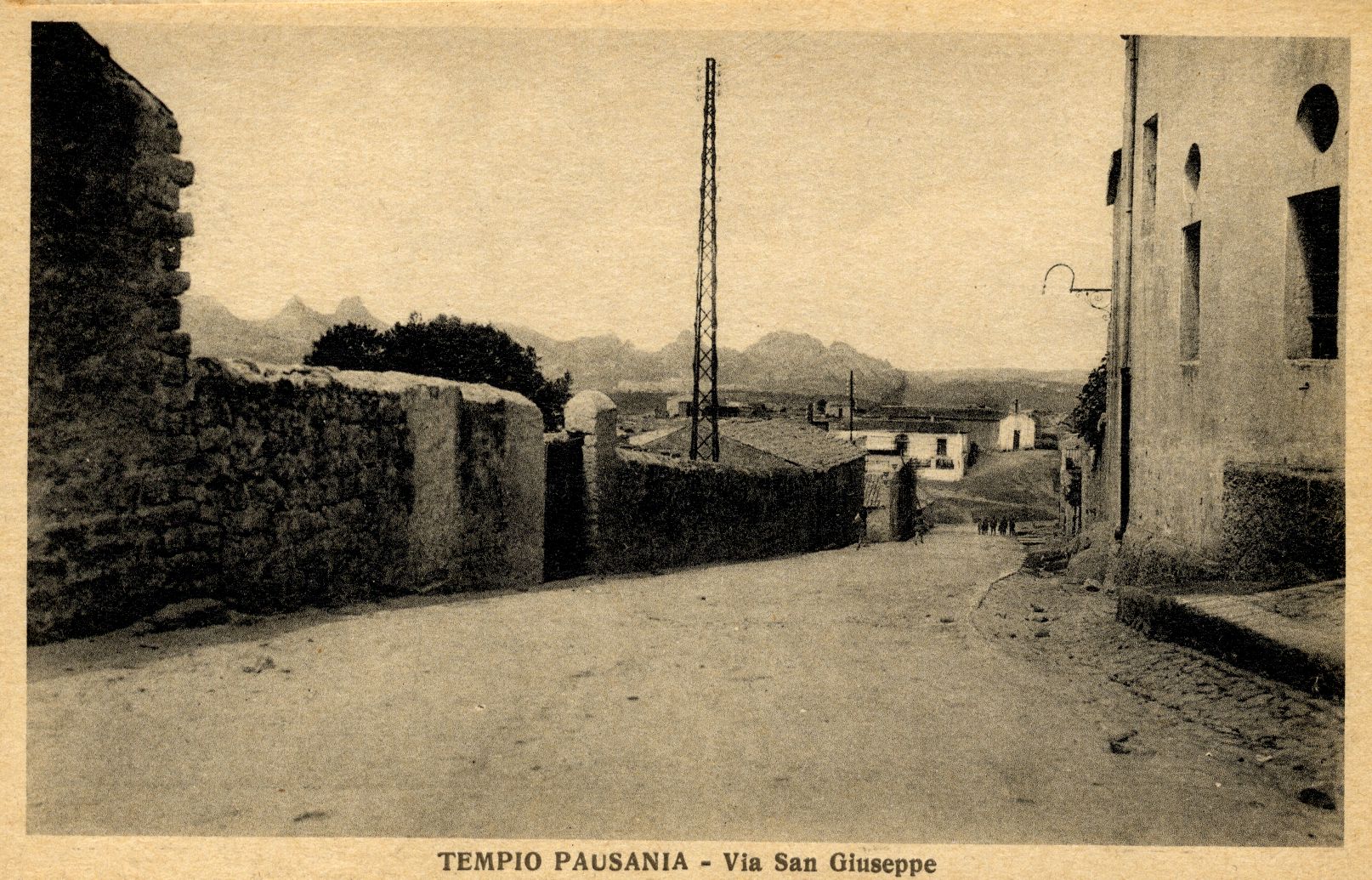

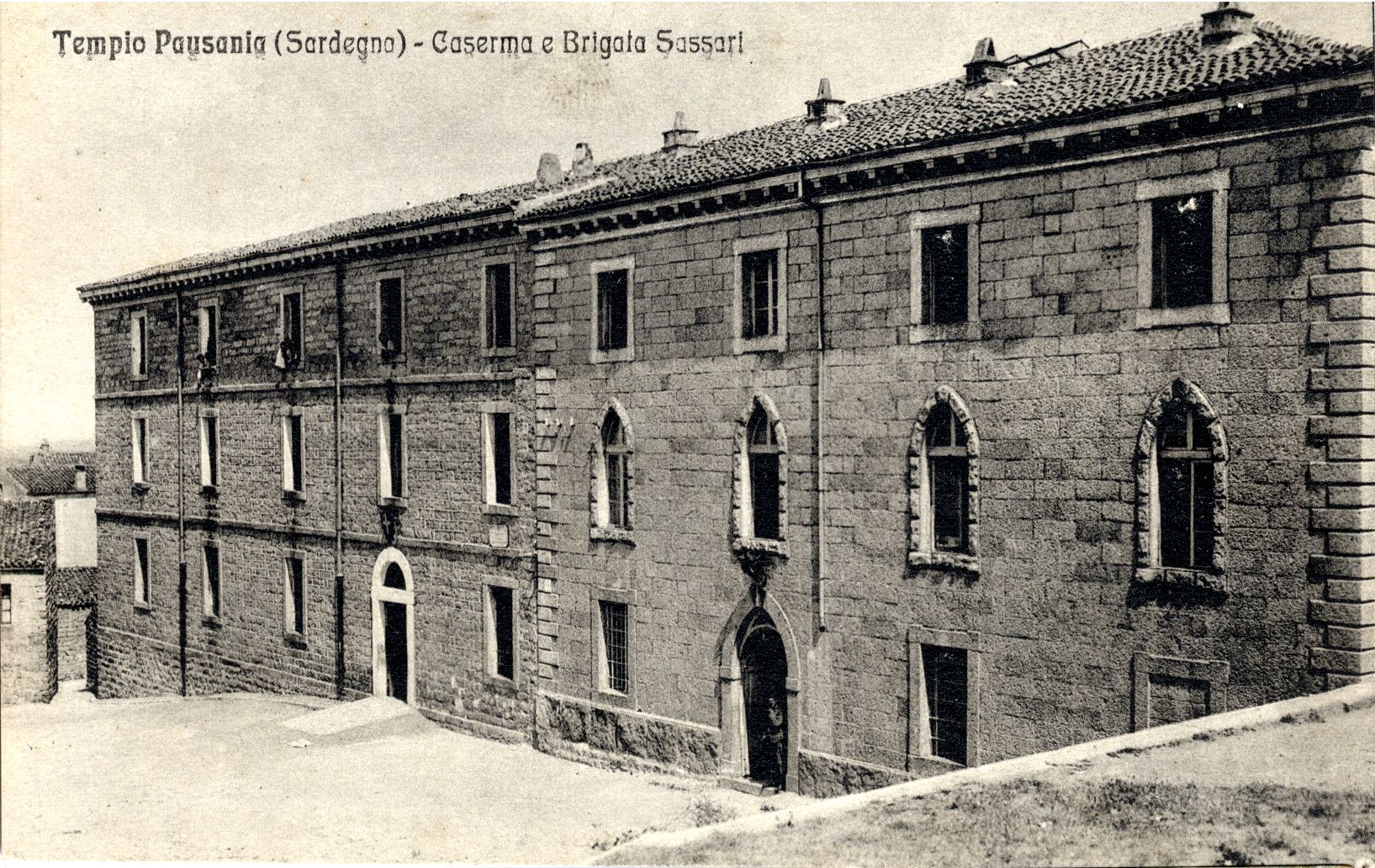

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

Collection Erennio Pedroni, Gianfranco Serafino, Rotary Tempio, Vittorio Ruggero – Tempio Pausania

Contemporary Photos

Antonio Concas – Flickr, HrodebertRobertus – Flickr, Carlo A.G. Tripodi – Flickr, Vittorio Ruggero – Flickr, Salvatore Carta – Instagram, Roberto Gamboni – Flickr, Davide Cioncia – Flickr, Salvatore Solinas – Flickr

![Militiamen on duty [clipping], 1826-1839 Militiamen on duty [clipping], 1826-1839](https://www.galluratour.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/6A-Cominotti-Gonin-Lallemand-miliziani-in-servizio-ritaglio-1826-1839.jpg)