LITTLE-KNOWN SARDINIA

[Many photographs by Charles Will Wright]

THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE ⇒

Vol. XXX, N. 2 – agosto, 1916 ⇒

Traduzione di Gallura Tour

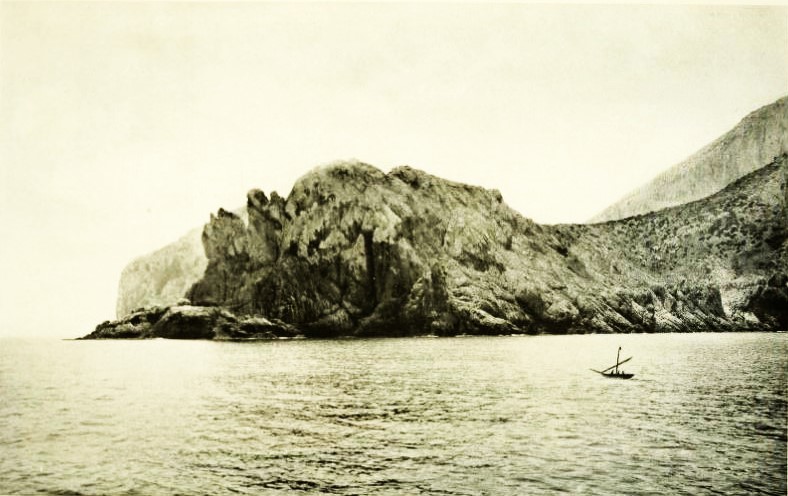

A VIEW OF THE ROCKY COAST NEAR THE NORTH END OF THE ISLAND

Cape Ferro is near the naval base of La Maddalena, on the northeast corner of Sardinia. Some miles south of this rugged point is the well-protected Gulf of Terranova and Golfo degli Aranci, where the traveler lands on the island after a night’s voyage from Civitavecchia, the port for Rome.

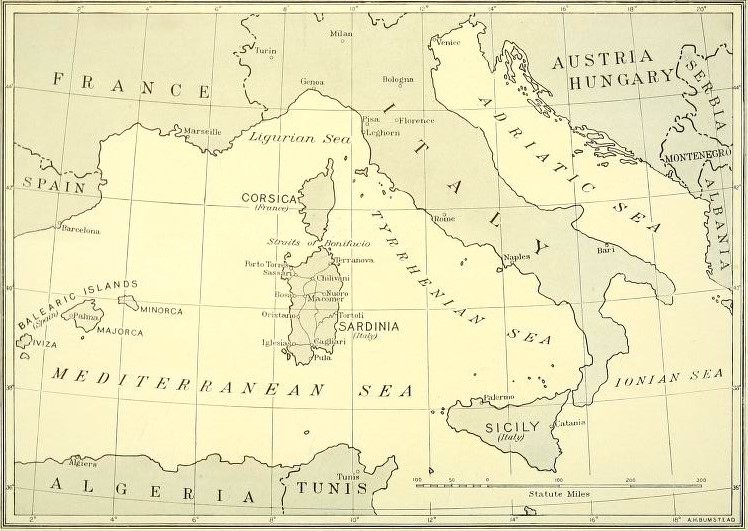

Those who have taken the Mediterranean route have at least had a glimpse of Sardinia from their steamer a day out from Naples. The island is in sight for some hours, and, if the steamer passes sufficiently close, a bold rocky coast can be seen on which Roman outlook towers remain similar to those scattered along the south shores of Spain. The tourist seldom includes a trip to Sardinia in his travels, as neither of his advisers, Thomas Cook nor Baedeker, recommends it to him. It, however, is one of the few foreign fields that has not been overrun and overfed by the tourist, and in many of the villages a traveler is still regarded as a guest and not as prey to be pounced upon.

Some day, when tourists are tired of taking the tours laid out for them by the guide-books, perhaps they will break away from the continent and set sail for Sardinia, especially if they are not traveling just to enjoy hotel comforts. One can rent a good automobile at Cagliari, and a week spent touring around the island would probably leave the pleasantest of recollections and an experience long to be remembered.

Sardinia can be reached by an eight hours’ night voyage from Civitavecchia, the port of Rome, to the north end of the island. The crossing on the mail steamer is quite comfortable, but the knowledge that one must get up at five the next morning is rather appalling. The beauty of the sunrise over the sheer cliffs and craggy isolated rocks of Golfo degli Aranci compensates, however, for this inconvenience and for the cup of bitter black coffee which comprises the break-fast.

As soon as one lands, a refreshing fragrance in the air is noticed – a perfume characteristic of Sardinia – not due, certainly, to orange trees, as is suggested by the name of the port, there being none in this district, but to the many wild herbs and shrubs all over the island.

The first couple of hours’ journey down the island is over a rough, rolling country made up of granite and resembling parts of Arizona or Montana. This apparent wasteland is used for pasturing goats, which feed on the shrubs. Here, as over most of the island, one finds the white flowering cystus, bright yellow ginestra, rosemary, a mass of blue when in blossom, and pink heather; also arbutus with bright yellow and red berries, thyme, juniper, and other shrubs.

THE SWITZERLAND OF SARDINIA

Excepting the eucalyptus and pine planted near the stations, there is a noticeable lack of trees along the railway routes. Among the mountains, however, which occupy the eastern half of the island and occur to some extent along the western coast, there are important forests of oak, ilex, cork, and wild olive; also areas reforested with pine and chestnut trees. In the mountainous areas of the island are many fertile valleys.

The scenery here compares favorably in grandeur with that of many countries of the world. The finest scenery is among the Gennargentu Mountains in the Barbargia Range, the highest peak being 6,233 feet above sea-level; on it there is usually snow from November to April. This region is called the Switzerland of Sardinia. In the other ranges are many picturesque peaks, as, for instance, Monte Albo, a group of limestone mountains with practically no vegetation on their slopes; so that the white mountains and the blue Mediterranean at their feet offer striking contrasts.

But, to return to the railway route, at Chilivani, one-third of the way down the island, is the junction of the road that goes west to Sassari, the capital of the northern province of Sardinia. This city is situated in the midst of a well-cultivated area, with groves of olive, almond, orange, and lemon trees and orchards of apples, peaches, cherries, and other fruits. The railway continues to the coast of Alghero, an interesting old Spanish port, at one time surrounded by a high fortified wall. It is here that Admiral von Tirpitz owns a large agricultural farm and has a villa, and where, at the beginning of the war, the Germans were suspected of having a base for supplying submarines.

To the south, about half way down the island, at Macomer, is another branch road to Nuoro, a distance of 35 miles and the center of a mountainous district, the Barbargia, which was at one time said to be the home of the famous Sardinian brigands. These are practically “extinct” now, although occasionally one hears of a man who has murdered a neighbor or a member of his family for some personal wrong and, in order to escape the carabinieri, or national police, flees to the mountains and lives as best he can, sometimes stealing a lamb or a goat from a shepherd or stopping a lonely traveler to ask for food or a few soldi. Unfortunately, the general impression outside of Sardinia, even in Italy, is that the island is more or less overrun by bandits; this is not true, and a traveler on the island today is even safer than he would be in southern Italy or Sicily.

MEDIEVAL TOWERS CROWN CAGLIARI’S HILLS

Macomer is the center of the region where many fine horses are bred for the army, as are also the small ponies used in Naples. After passing this town, the railroad descends to Oristano, on the west coast, noted for its pottery and particularly its delicious pastry and almond sweets. The road then runs diagonally across a valley, from 10 to 15 miles wide, which extends down to Cagliari, at the southeastern end of the island.

Cagliari is the principal port of Sardinia, and is often visited for a few hours by tourists taking the weekly steamer from Genoa and Livorno to Tunis. The bay of Cagliari is most impressive. On the right and left as you enter are hills, with mountains in the distance, while rising up from the lowlands directly opposite the entrance is the city, on a rocky hill 400 feet high. The top of this hill is encircled by a massive wall, built by the Pisans in the thirteenth century. At two of its angles rise the towers of the Lion and the Elephant, but of the tower of the Eagle, which completed the triangle, only the base remains. In the center of these fortifications is the old town and the cathedral. On the slopes of the hill outside the walls is built the modern city.

Surrounding Cagliari are shallow bays, which extend inland for many miles, and are of interest because of the government salt recoveries, where huge mounds of salt, 20 to 40 feet high, can be seen on the flats. In the spring flocks of flamingoes and other birds congregate on these lowlands and add to the beauty of the scenery.

The land around the lagoons is especially fertile and well cultivated with truck gardens and vineyards, from which a very large quantity of wine is made. Cagliari, the largest city on the island and the capital of the southern province, has about 53,000 inhabitants. The entire population of the island is estimated at 796,000, a density of population of 85 per square mile; this is a much lower figure than in any other part of Italy. Among the objects historically interesting in Cagliari are rock-cut tombs on the hillside below the Castello. These are probably of the same period as the “nuraghi,” the famous prehistoric remains in Sardinia, and some may have been enlarged by the Romans into the tombs. which still exist, well preserved and with Latin inscriptions on their walls.

A PANORAMA OF CAGLIARI FROM THE HARBOR

The principal city of Sardinia is this town of 53,000 inhabitants. It was founded by the Phoenicians and has been the scene of many striking episodes in the history of the island. In the year ICOO it was the stronghold of the Saracen chief Musat, who, after many years of war, was finally driven out by the Pisans, the latter having been promised the island by Pope John XVIII provided they evicted the Mohammedans.

STRANGE RELICS OF THE BRONZE AGE

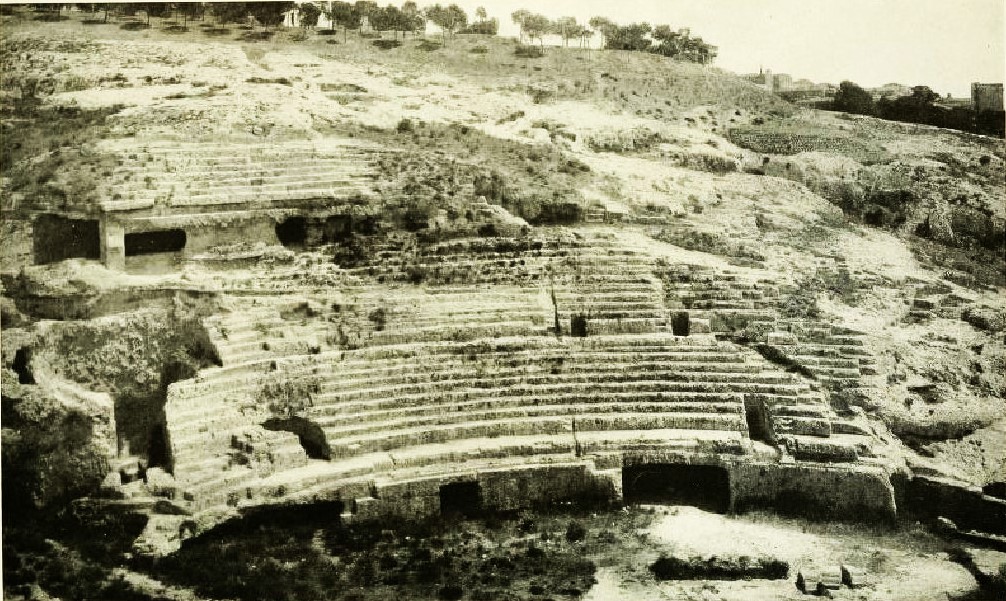

Of the Roman period an amphitheater remains. This is on the side hill to the Photograph by C. W. Wright west of the city and is fairly well preserved, with the passages under the tiers of seats. The work of the Pisans in the cathedral was begun in 1312 A. D. and finished by the Aragons in 1331, but later partly rebuilt by the Spaniards in 1669. Among the modern buildings is a beautiful city hall, recently completed; a university with its library, which has a valuable collection of manuscripts, among them a code of laws made by Eleanora of Arborea, who was a ruler of a part of Sardinia when it was divided into four provinces under the Spaniards. The southeastern corner of the old fortifications has been remodeled to form a “piazza” above the city. Here concerts are held at midday on Sundays during the winter months and on summer evenings. It is the fashionable promenade, as is also the Via Roma, a boulevard along the edge of the bay.

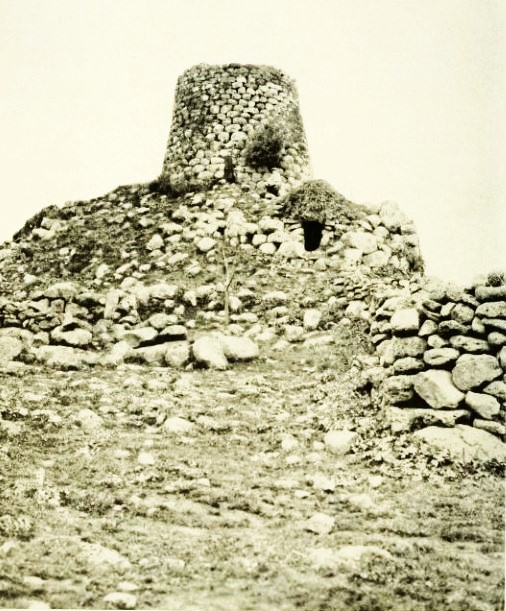

Throughout Sardinia prehistoric monuments are prominent in the shape of truncated cones about 30 feet in diameter at the base and built of large rough blocks of stone about 2 feet high and of varying lengths.

These towers are the “nuraghi” belonging to the Bronze Age and show that the island must have been well populated in the centuries antedating the Christian era. The entrance to the “nuraghi” usually faced the south and served to light the circular room within, as did also a door opening to a spiral staircase built in the walls and leading to a chamber above the ground floor. Few of the “nuraghi” have the roofing preserved entirely, so that we no longer see them in their. full height or original cone shape. Some have two or three chambers on the ground floor with niches in the walls, probably for household gods. These towers were undoubtedly fortified habitations.

They are usually situated in commanding positions at the entrance to tablelands, near the fords of rivers, or on almost inaccessible mountain peaks, and within signaling distance of one another. Traces of at least 5,000 “nuraghi” have been found.

The ancient tombs of the inhabitants of the “nuraghi” are usually found near them. These are called the “tombs of the giants,” and are chambers 32 feet wide and from 30 to 40 feet long, with a roof of flat slabs of rock and with the sides made of the slabs or of rough walling. The bodies were probably arranged in a sitting position. In front of the tombs are circles about 40 feet in diameter, surrounded by stones; these were, no doubt, used for sacrifices and burial rites.

Another type of tombs found in Sardinia is that of the small grottoes cut in the rock like those in prehistoric cemeteries in Sicily. In these tombs and in the “nuraghi” sarcophagi were discovered, generally of marble; also idols consisting of small bronze figures varying from 4 to 17 inches in height, images of dogs, bats, apes, and other animals-all most crude in workmanship and grotesque in form; medals, coins, vases, ornaments, arms, and articles of terra-cotta and glass. Most of these latter must antedate the Roman occupation. Some of these relics and similar objects, including articles of jewelry dating from the Roman occupation, can be seen in the Museum at Cagliari.

REMAINS OF AMPHITHEATER, NEAR CAGLIARI

This extensive ruin, with its rock-hewn benches, is a relic of Roman occupation. Sardinia furnished more human victims for the games in the great capital of the ancient world than sports for its own people. It is recorded that Sempronius Gracchus, after quelling two insurrections of mountain tribes, took 80,000 Sardinian slaves to Rome.

NURAGHE, TO THE NORTH OF MACOMER

Numerous prehistoric monuments like this relic of the Bronze Age dot Sardinia. The arrangements of the interior of these structures are such as to indicate that they were used as fortified habitations and not as tombs or temples. The diameters of these truncated cones range from 30 to 100 feet at the base, and they are from 30 to 60 feet high. The entrances, about 6 feet high and 2 feet wide, almost invariably face south.

LANGUAGE REFLECTS MANY RACES

The Phoenician settlement is the earliest of which there is any accurate knowledge. Sardinia was said to be the grain-producing center of the Carthaginians about 500 B. C. The Romans captured it in 238 B. C., and it was then noted for its supply of corn. The Romans built many towns and roads, and remains of their monuments, temples, and sepulchers are still preserved.

The Byzantines captured Sardinia from the Romans and held it until the tenth century, when the Saracens took possession, and were in turn driven out by the Pisans. There are traces of the influence of Pisa in the fine Romanesque churches which are still well preserved. In some churches the late Gothic architectural style shows Spanish influence, which came after the surrender of the Pisans to Genoa, and then to James II of Aragon. In 1708 Cagliari surrendered to the English, but in the War of Spanish Succession the island came under the rule of Austria. Finally, after more exchange, it was given to the Duke of Savoy, who acquired with it the title of King of Sardinia.

It is not strange that the language of the people should contain elements of the languages of all the races which have occupied the island. The dialects, of which there are five or six, are a mixture of Latin, Spanish, and Italian, with a little Phoenician and traces of other ancient tongues. In Alghero, on the west coast, pure Catalan is spoken; in some villages almost pure Latin; and in Carloforte, on the southwestern coast, the Genoese dialect prevails. Italian, however, is now taught in the schools to the children, while the men acquire it during their compulsory military service.

To get an insight into the life of the inhabitants of this isolated island, one should visit its villages. It is in the entire eastern half, with its mountainous valleys and villages, where the real Sards now live. Here one will find them good looking and in good health, generous, hospitable, honorable, and quite poor. liteness is carried almost to an extreme. Often as one rides through a small village the women, children, and old men sitting at the doorsteps rise and wish you a “buon viaggio”; or if it happens to be noon, some may wish you a “buon appetito.” Even the young boys are taught to take their hats off when strangers pass by; and if one is in an automobile and happens to stop to get out his kodak, a crowd of youngsters seem to spring up around the car, all anxious to be in the picture. To refuse a cup of coffee or a liqueur when visiting the house of an inhabitant of a village is an act of great discourtesy, and even the poorest have some beverage to offer.

BENEATH THE TOMBS OF THE ANCIENTS – Photograph by C. W. Wright

Viewed from a distance, these holes in the mountain side resemble natural caves, but they are the rock-hewn mausoleums of the “nuraghi,” and are known as the “domus de gianas,” or houses of the spirits. In contrast to these burial places are the “giants’ tombs,” crude sarcophagi of the prehistoric inhabitants of Sardinia, from 30 to 40 feet in length and 32 feet wide and high.

A SARDINIAN SHEPHERD AND HIS FLOCK – Photograph by C. W. Wright

The donkeys of the island are remarkably small, as this typical mount of the herder shows. The sheep are prized not only for their wool, but for their milk, which is converted into cheese and sold on the continent as the Roman product.

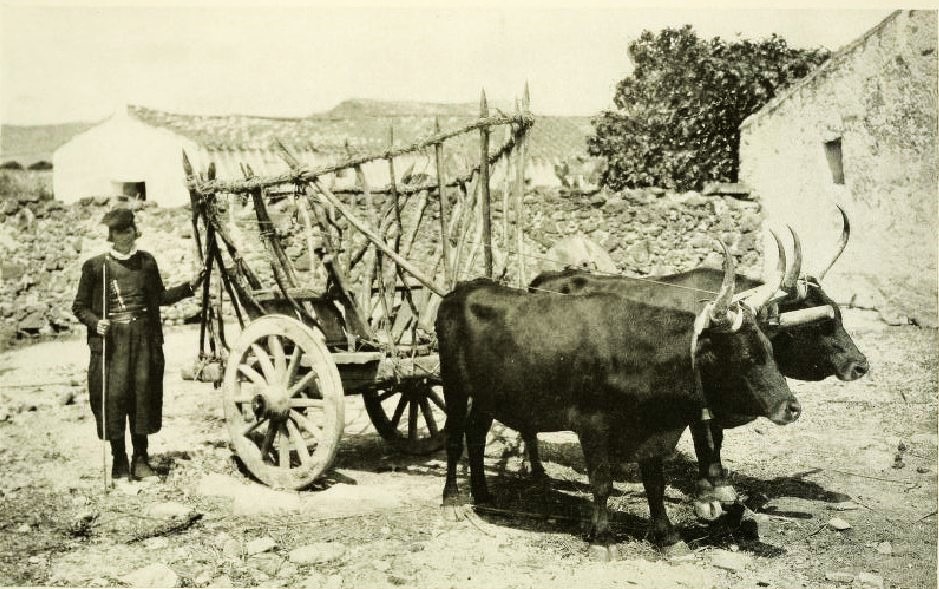

TWO-WHEEL TRANSPORTATION IN SARDINIA

During the era of Roman occupation nearly 1,000 miles of roads were constructed on the island, and some of these are still well preserved. Although small, the Sardinian oxen make good draught animals.

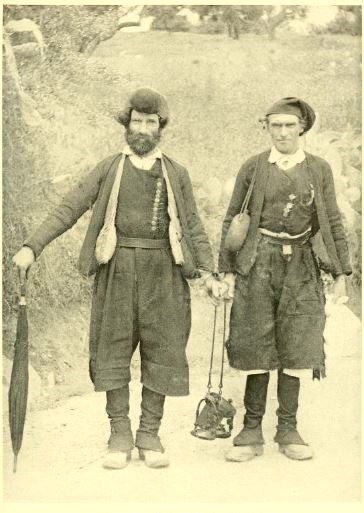

SHEPHERDS OF POVERTY-STRICKEN SARDINIA – Photograph by C. W. Wright

One glimpse at this trio would be enough to send a shudder down the spine of a stranger who has feasted upon the out-of-date tales of bandit-ridden Sardinia, but these three cronies are harmless natives, who, in spite of their bitter fight against heavy taxes and the relatively high cost of living, never annoy the tourists by begging, as do so many of the people of southern Italy.

GIRLS AT DORGALI

Note the queer bonnets worn, made of many-colored silk.

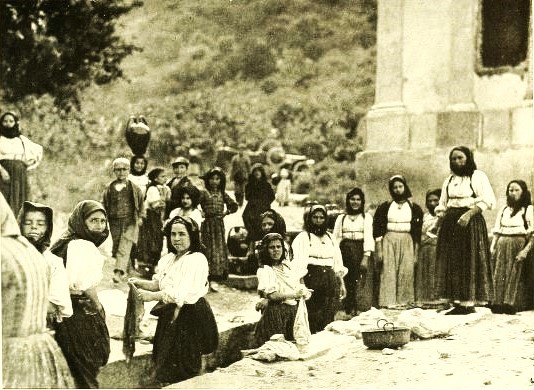

THE COMMUNITY LAUNDRY TUB – Photograph by C. W. Wright

Every day is wash day in Sardinia, and the public fountain takes the place of the village well of the Orient and the sewing circle of the Occident as a social center.

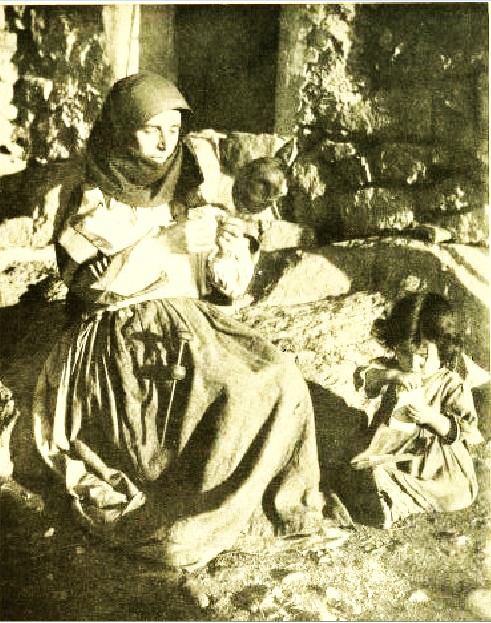

A DOMESTIC SCENE IN SARDINIA

Many of the people of the island are victims of abject poverty, but their condition is not due to lack of industry. The styles never change among the women, who wear the native costume; so it repays the seam-stress, the weaver, and the embroidery expert to make garments that will last a lifetime, and can then be handed down as heirlooms for rising generations.

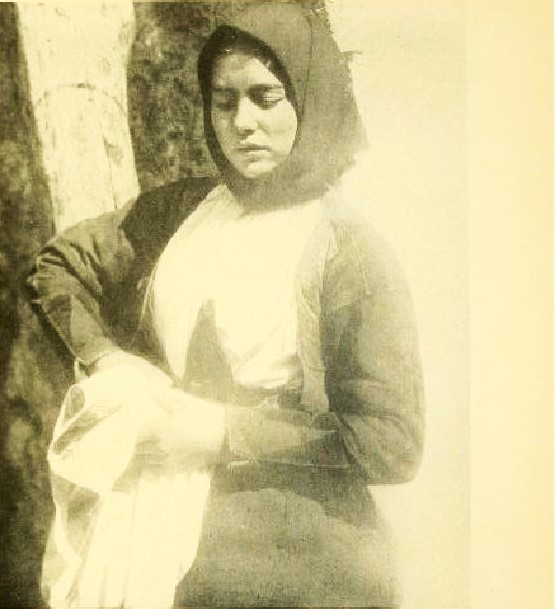

A SARDINIAN MAIDEN

Not only in their features, but in their language, do the natives retain traces of the many races which have occupied the island through the centuries-Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Saracens, Italians, and Spaniards. Many dialects are spoken, but Italian is now taught in the schools, and the men acquire the official language during their period of compulsory military service.

SARDINIAN BREAD, MADE ON FESTIVE DAYS

The bread is a pure white, of fine texture, and is kneaded for hours before baking. The fair bakers are wearing their most elaborate costumes, reserved for religious festivals and holidays.

NATIVES EXCESSIVELY POLITE

Generally speaking the peasants seem to be somewhat downtrodden and do not realize their just rights. We thought the attitude of the man in the following incident most unusual: When motoring along one of the straight roads down through the valley to Cagliari, we saw a man ahead on horseback. He jumped off in a great hurry and, holding the horse by the end of the reins, got down into the deep ditch at the side of the road. As the car came up he was so interested in probably the first automobile he had ever seen that he forgot his horse, which, unexpectedly, gave a jump down into the ditch almost on top of the man, upsetting him and his saddle-bags into the mud. When we stopped to examine the harm done and to help him up he was very gratified and most profuse in his apologies for having disturbed us, saying: “Excuse me, excuse me; it was all my fault.”

The music of the Sards is characteristic; not all quick and vivacious like that of the Sicilians or other southern Italians, but monotonous and slow, resembling very much the music of northern Africa. Often a long song will be sung to one phrase of a melody, like a sorrowful chant. The accordion is a favorite instrument, and in the villages on Sundays or other festas most of the inhabitants congregate in the principal piazza and dance to its music. The men and women form in a circle and dance slowly forward and backward, some of the younger men adding more complicated steps, occasionally breaking away from the circle and dancing with their partners; but the whole effect is dignified and staid.

Each “paese” or village has its annual festival to celebrate the birthday of its own particular saint or some other church feast. The most renowned of these is the “festa” of “Saint’ Efisio,” the national feast of the island. The ceremony is in the form of a procession from Cagliari to Pula, a village 9 miles away, with the return to Cagliari. The saint was an official in the army of Diocletian, and for his conversion to Christianity was beheaded at Pula. On midday of May 1 the procession leaves and returns on the evening of May 4. It is composed of a cavalcade of horsemen all in the costume of the ancient Sardinian militia, escorting the image of the saint, which is preceded by musicians playing the “launeddas,” an instrument made of three or four reeds of different lengths and like the pipe of ancient times.

In the region about Iglesias where the mines are, the workmen celebrate annually the festa of Santa Barbara, “the god of fire,” which usually results in much wine drinking, followed by a few days’ absence from work, so as to recuperate.

CAVALCADE OF HORSEMEN AND HORSEWOMEN STARTING ON A PILGRIMAGE TO A SMALL CHAPEL IN THE COUNTRY

The banners carried by the leaders and the bright colors of the costumes make a striking picture. The saddle-bags are usually well filled in preparation for the feast.

A LOVE SONG ON THE LAUNEDDA

This Sardinian musical instrument bears a striking resemblance to the pipes of the ancient Greeks. The serenader is wearing a sheep-skin mantle, which, in addition to being his “Sunday best,” is his talisman to ward off fevers.

DIES “GIOCARE ALLA MORRA!” – Photograph by C. W. Wright

The game of “morra” holds for the man of Italian blood the same allurements that poker holds for some Americans, and that “craps” has for the southern darky. So excited do the morra players become over the hazards of this, their national betting pastime, that tragedies not infrequently result; hence the police frown upon the practice, but always with a certain fond indulgence. It is played entirely with the fingers and consists of trying to guess how many fingers your opponent will hold out at the instant he acts. It is more difficult than it sounds.

PICTURESQUE COSTUMES OF SARDS

The Sards’ costumes are one of their greatest attractions. They are of rich, harmonious, though brilliant, colors, each village having its own distinctive type, which does not change from year to year; so the men and women are thus known by the clothes they wear. Unfortunately the general European type of dress is being adopted by the younger generation, and it is now difficult to find many towns in which the native dress is used by all the inhabitants.

There are a few such villages up in the mountains near Nuoro, where the railroad has not penetrated, and here it is most interesting to see the women and little girls all dressed alike. The skirts are usually very full, accordion plaited in some villages, with a distinctive trimming; white waists with full sleeves, and over these short jackets, open in front or laced around the waist. All in a town have the same combination of color, perhaps a dark red skirt and the jacket in bright red and bright blue, a diagonal stripe of each color meeting in the back, and with tiny bonnets of the two bright colors. In some the most distinctive characteristic is the covering of the head-a bright-colored handkerchief or a white veil folded back or held in place by a silver chain under the chin; in other towns the apron is characteristic in its color and shape.

The most elaborate dresses are, of course, kept for festas, and these have hand embroidery and are often of very heavy silks and brocades, sometimes with exquisite lace scarfs or veils folded back on the head. The jewelry is most elaborate, too-large gold buttons worn at the throat; large earrings and pendants. The costumes and jewelry are almost always heirlooms in the families.

The men’s costumes usually consist of woolen leggings, white, full trousers, long or short, a full ruffle of black cloth worn around the waist; and this, too, differs in length. Some of the jackets are short and some long, but all have silver buttons down the front. The shepherd wears a sheepskin, on which the wool has been left, over his shoulders throughout the year, even in midsummer, and claims that it keeps away the malaria. In some districts the men wear a pointed cap resembling a Phrygian bonnet, long and narrow like a stocking, reaching almost to the waist; the point is either worn down over the shoulders or folded on the top of the head and may be used as a pillow at night. It is apt to contain anything from bread to snuff, which is indispensable to the older Sard. A queer custom of some of the younger men is to let the hair on the top of their heads grow often to 15 inches in length, and then roll it up into a puff, which looks like a pompadour, across the forehead.

Among the distinctive products of Sardinia is cheese made of goat’s milk and used very generally by Italians. The wines are noted for their strength. An interesting export is cork, which is taken from the trees every five years, leaving the bare, red trunks noticeable all over the island. Many sheep, goats, pigs, cattle, and horses are raised and sold on the continent.

SARDINIAN MINERS ON THEIR WAY TO WORK – Photograph by C. W. Wright

Fifteen thousand natives find employment in the mines of the island. The center of this industry is in the southwestern corner, in the vicinity of Iglesias. Lead and zinc are the principal minerals, but silver, iron, antimony, coal, and copper are also produced. During the Spanish occupation of the island the mines of Sardinia were abandoned, for the soldiers of Aragon and Castile had discovered the fabulous wealth of the Montezumas and the Incas in the New World.

COSTUMES OF ARITZO, CENTRAL SARDINIA

Just as the girls of the various towns and provinces of Holland are to be distinguished by the peculiar form of their quaint head-dresses, so the girls of Sardinian villages are known by the combination of colors in their costumes. The women and children dress alike-full skirts, usually dark red; white waists with full sleeves, and short bright red or bright blue jackets, open in front or laced around the waist. In some districts the pattern of the apron is the distinctive feature.

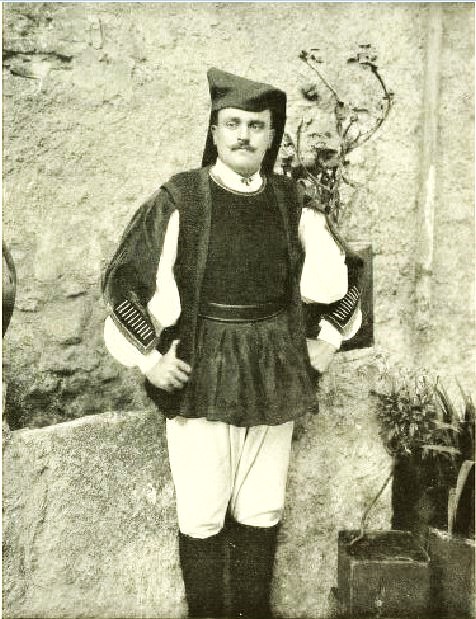

THE COSTUME OF NUORO

The large white sleeves beneath the slashed sleeves of the jacket; the full, short skirt and close-fitting trousers, are typical. One would think the man had stepped from his place in a pageant of the Middle Ages instead of being garbed in this customary costume for feast days.

GREETING THE TOURIST WITH A SMILE – Photograph by C. W. Wright

Politeness is one of the striking characteristics of the Sardinians. As the traveler rides through a village the women, children, and the old men sitting at the doorways rise and cheerily cry out “Buon viaggio.”

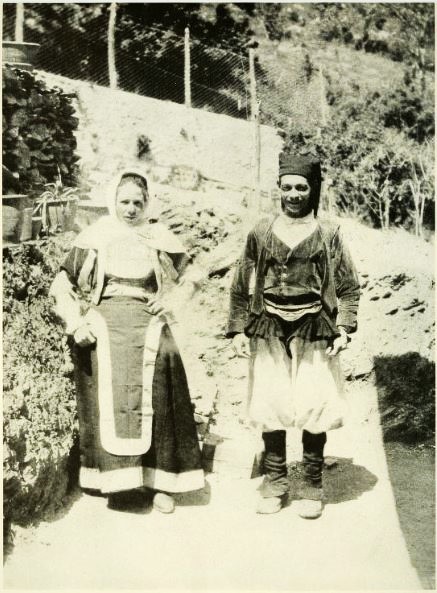

A YOUNG MARRIED COUPLE OF IGLESIAS

The Sardinians have a high regard for womankind. They are a vigorous, hospitable, grave, and decorous mountain race, suspicious of all innovations. The silver buttons and voluminous trousers of the bridegroom are typical.

IMPORTANT MINING OPERATIONS

The mining industry is probably the most important, the principal metals produced being lead and zinc. Iglesias, in the southwestern corner, is the center of mining activity. The mines employ about 15,000 workmen, and the output. approximately 60,000 tons of lead concentrates and 120,000 tons of zinc concentrates annually. Some silver, iron, antimony, copper, and coal are also produced.

The tunny fisheries off the island of San Pietro are noteworthy. In the spring schools of these fish pass through the Mediterranean, and enormous numbers are caught in nets and brought to the large canneries at Carloforte.

There is very good hunting on the island. The moufflon, a cross between a wild sheep and a deer, is found in the mountains and is native only to Sardinia; there are also some fallow deer and red deer. By far the most numerous of the big game is the wild boar. Hare, partridges, woodcock, snipe, quail, and wild duck are all found in large quantities.

TUNNY FISHING AT PORTO TORRES

We get the word “sardine” from Sardinia, but we get few sardines, for practically all of this “catch” is consumed locally. The tunny fisheries, on the other hand, are important and profitable. The Genoese control this industry on the island, for the Sardinians are not a maritime folk.

AN ISLAND OF WILD FLOWERS

The wild flowers are most beautiful, and there is practically no month in which a great variety is not found. Among these are orchids, narcissus, lilies, gladiolas, irises, cyclamen, fox-gloves, poppies, and sweet peas. In the summer months, usually from May until September, there is no rainfall. During the winter the rains are heavy and often accompanied by strong winds. In the northern part of the island a good deal of snow falls, and often the ground remains covered for a month at a time; but in the southern part of the island there is almost never any snow and seldom any frost. In the gardens there roses, heliotrope, calla lilies, nasturtiums, ivy, geraniums, marguerites, and many other flowers bloom all winter. It is during the summer that these cease blossoming.

May, June, and October are the months most pleasant for travel in Sardinia. The country is at its best then; the cultivated fields green, the wild flowers most profuse, the climate least variable, and the roads, which are covered with “ghiaia,” or broken rock, from December to February, are then in perfect condition.

GATHERING THE WHEAT – Photograph by C. W. Wright

Harvesting machinery is seldom seen in Sardinia. The head-dresses of these two reapers are peculiar to the island. This type of cap not only furnishes a covering for the wearer’s head, but is an improvised lunch bag, from which he will abstract a loaf of bread at the noon hour. At night it serves as his pillow.