FROM SANTA TERESA TO TEMPIO

(and Gallura traditions)

by George Burdett

Traits of Corsican and Sardinian Character

in «The New Monthly Magazine and Humorist»⇒

London, January – February 1845

The next day I agreed with a viaggante, or pack-horse carrier to take Ferdinand and my baggage to Sempio, for twenty-four reals (twelve francs), for which sum two horses were to be forthcoming.

Our friend, the viaggante, however, with true Punic faith, brought only one to the post in the morning, the other was said to be knocked up and unable to travel. The one, which appeared at the door accoutred, had a saddle which bore strong marks of eastern origin, very high in the pummel and cantle, and with barely room for the horseman.

To this, the cloth saddle-bags of the country were strapped on, and, like Grimaldi’s breeches pockets swallowed up every thing that was thrown into them; one by one disappeared, bag after bag, valise after gun-case, and barrel-case after rollers and cloaks, till the bloated monsters almost trailed their length on the ground. On this foundation Ferdinand was hoisted up, but the temple of leather was destined to have another pinnacle besides himself.

We had hardly left Lungo Sardo a couple of miles behind us, when the viaggante jumped up on a large pad on the croup of his horse, which, though barely fourteen hands, carried this increase of weight gaily at least two-thirds of the journey, the whole distance being forty miles. I calculated that with the addition of the viaggante, the horse trotted along under four-and-twenty stone weight.

The bridle-track from Longo Sardo to Sempio, for it deserves no other name, passes through a country of untold magnificence in point of scenery. At times one sweeps through forest trees, rivalling in luxuriance the New Forest, over the greenest turf, and along the banks of streams clearer than crystal, sometimes through deep woods of cork and holm oak; sometimes one toils up rugged peaks, and ever and anon, plains of immense extent are crossed, the whole a desert of the wildest beauty.

This district formerly abounded in robbers, who had the audacity to take powder and balls from travellers, load their long Sardinian guns, and then rob the unfortunates, who thus surrendered their only means of defence.

On our journey we met five or six travellers coming in an opposite direction; they were all mounted, and with one exception, a curate, armed.

Behind one man was strapped a table; behind another, two chairs; behind a third, a large iron pot; all carried en croup some piece of furniture. I set them down as a marriage party going to furnish the bride-groom’s house.

[…] Il ballo tondo

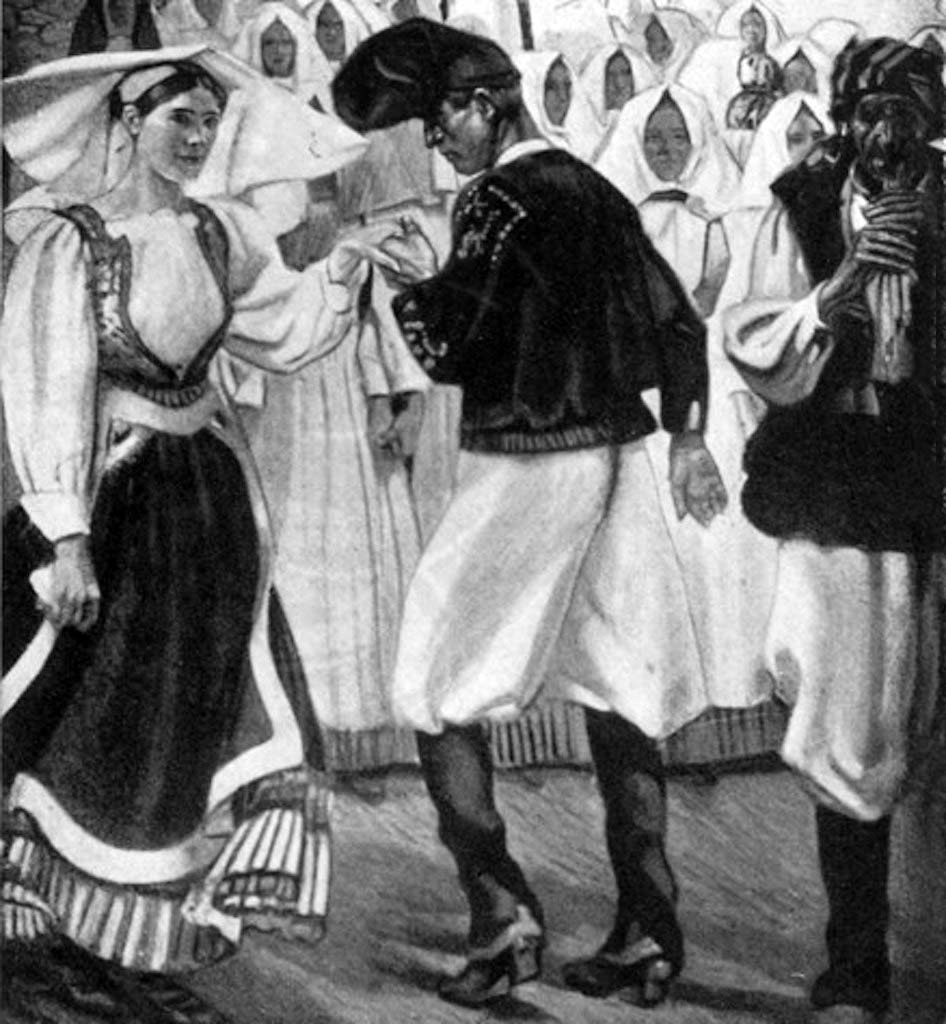

When shooting in the mountains of Gallara, amongst the wild shepherds of that savage district, I had several opportunities of seeing the Sardish national dance, the Ballo Tondo.

Four shepherds stand together in the centre of a hut, and, having drawn their hunting knives, hold them upright on their cartridge belts. One of the party then begins a chaunt on love, war, or the pleasures of the chase, to which the others add obligato accompaniments, and this extempore singing is kept up for four or five hours together.

Round the singer, meanwhile, a circle of men and women, holding each other by the hand is formed, who dance to exhaustion, when their place is supplied by others, who do not, however, prevent the general movement for a moment. Although this dance appears at first sight rather easy, it is, nevertheless, difficult for those who have not learnt it in infancy.

Strangers sometimes attempt it, but they are soon obliged to retire, if they do not wish to amuse the natives at their expense, and even cause the failure of the amusement, for a single dancer who does not observe the proper measure and cadence, disconcerts all the others. There are certain rules which must be strictly observed in dancing the Ballo Tondo, and the infraction of which often leads to bloody quarrels.

Affianced persons can alone hold one another by the hand palm to palm, or with interlaid fingers. Any man who thus held a girl whom he was not disposed to marry, or another man’s wife, would run considerable risk of assassination.

The lannedda is a musical instrument peculiar to Sardinia, the use of which is gradually becoming extinct in the northern parts of the island.

When I was at Terranova I rode up to a solitary hut in a mountain de- file, about ten miles from the town, inhabited by the last of the race of minstrels who were skilled in its touch. On inquiring for this last scion of an honoured stock, I was told by fine-looking man of about forty that his father, the player, was out chopping wood, but that he would send for him immediately.

In about half an hour a shepherd, eighty years old, walked into the hut, the very picture of green old age. His hair was as white as snow, but not thinned by time; it fell in clusters over his shoulders, which were broad and flat ; his complexion was of a clear brown, and his eye still glowed with all the fire of the south.

On my asking him to play, he took a tin case from the wall, out of which he drew three reed pipes of unequal length, the longest of which was about twenty inches. This instrument is a relict of the very highest antiquity, and has survived in Sardinia all the revolutions to which the country has been subject from the time of the earliest Roman dominion to the present hour.

It is composed of two, three, and sometimes four reeds (three is the more common number) of unequal length and thickness, and pierced with several holes, like ordinary clarionets.

The musician places them all in his mouth, and plays on them at the same time. The tuning is finished by shifting little pieces of wax with the fingers up and down the holes on the outside, which are generally about half an inch square, and considering the clumsiness of the process, it is generally soon over.

When the instrument has three pipes, two are nearly of equal length, but the third, which is always placed on the outside, is considerably longer and thicker; it has only one hole, and gives forth a mellow bass sound like the drone of a bag-pipe. The other pipes execute airs of accompaniment, first, second, &c.

The sound of the lannedda falls wildly and strangely on the ear at first, but those who have been accustomed to the spirit-stirring thrill produced by the bagpipe feel a long-forgotten pleasure revive in listening to its strain. In effect the notes of the lannedda hold an intermediate place between those of the bagpipe and the organ, except that in playing the Sardinian pipes the final sounds are less prolonged.

The Sardish minstrels are generally victims to their efforts. In most cases they become fatigued and exhausted at an early age. Some of them can play for two hours together without taking the instrument from their mouths. These exertions have produced changes in the form of the lannedda in the southern part of the island; a common mouth-piece, like that of the double flageolet has been added to all the pipes, which greatly lessens the fatigue of the player.

There can be no doubt but that this national instrument is exactly similar to the tibiæ pares et impares of the Romans, with which every “Westminster” is so well acquainted.

[…] In the northern province of Gallivia the dress of the men is the same during summer and winter, an illustration of the practice of southern nations, who guard the person as carefully from the rays of the sun as from damp and cold.

The cabodano is a loose coat with wide sleeves and a hood, which enwraps the outer man to the knees, shapeless as the “pilot,” which of late years has been so much the fashion, and of a rough black cloth resembling that comfortable texture, and woven in the shepherds’ huts. Under this is a tight-fitting waistcoat, which is met in its descent by two pairs of trousers; the first is of coarse white linen, and reaches to the ancles; the second is drawn over the first, but comes down only to the middle of the thighs — this latter is of the same stuff as the cabodano, and is made very full.

The under trousers, when the wearer is travelling, are tucked into a pair of black-cloth gaiters, which, with shoes of home manufacture, complete the male costume in the northern provinces.

The hair falls over the shoulders in locks more tangled and dishevelled than those of the King of Elves, and is generally surmounted by a black cap; while a beard, often the growth of a quarter of a century, reaches to the hilt of the hunting-knife, which is worn in the cartridge-belt.

E scomposte le chiome in sulla testa,

Come campo di biada già matura

Nel cui mezzo passata e la tempesta.

Disorder’d locks around his forehead waved

Like a vast field of laid but ripen’d corn

Which hath the fury of the tempest braved.

Contemporary PhotosSOURCES OF THE ILLUSTRATIONS

19th century drawings, paintings and lithographs

Michel Antony Shrapnel Biddulph, “La valle del Liscia”, ca 1858, IN Thomas Forester, Rambles in the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, Londra 1858; edizione italiana Come due vagabondi. Due ufficiali inglesi nella Sardegna dell’Ottocento, curato e tradotto da Maria Laura Argiolas, Cagliari, Condaghes, 1996.

Alessio Pittaluga, Gallura Shepherd, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes par A. Pittaluga [litografia incisa da Philead Salvator Levilly], Paris – P. Marino, Firenze – Antonio Campani, 1826, rist. Carlo Delfino 2012.

Lorenzo Pedrone, Gallura Shepherd, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

William Light, Jan Micali, Porto Pollo, 1829-30.

Contemporary Photos

Antonio Concas – Flickr; Roberto Gamboni, Aurelio Candido – Flickr

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

![Michel Antony Shrapnel Biddulph - Valle del Liscia [immagine nel libro], 1858](https://www.galluratour.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/1B-Biddulph-la-valle-del-Liscia-1858.jpg)