GARIBALDI AT HOME

NOTES OF A VISIT TO CAPRERA

by Charles Rhoderick McGrigor

London, Hurst and Blackett, 1866

WE PROPOSE THE FOLLOWING LARGE AND SELECTED SELECTION OF CHAPTERS AND PARAGRAPHS

from the CHAPTER I. (pp. 27-35)

Secure a Passage for the Maddalena – On board the Umbria – Capraja – An Italian Professor – Capo dell’Orso, and other Islands – Arrival at Caprera

from the CHAPTER II. (pp. 39 – 82)

The Wind at Caprera — On Board the Yacht — A Dangerous Channel — Garibaldi’s Seamanship — Tavolara — The Goats of the Island — Its Population — Extemporizing a Dinner — Sardinia — Night in the Gulf of Congianus — Chase for a Sard — A Sardinian Cottage — Garibaldi’s Island Home

from the CHAPTER III. (85-111)

The Maddalena — Why Garibaldi fixed his Home in Caprera — Longevity in the Maddalena — Porto Pollo — The First House built in Caprera — Rape of the Women of the Maddalena — The Maddalena and Neighbouring Islands appropriated by Sardinia — Formation of a Naval Depot — The Roads of Agincourt — The Mountain Tejalone — Good Company while Reading — The Cavallo — A Flock of Bishops in Sardinia — Silence of History regarding Caprera — Capraja — Climate and Soil of Caprera — Cultivation of Cotton in Sardinia retarded by the Ignorance and Intolerance of its Inhabitants — Garibaldi’s Desire for the Increase of Commerce with England — Chutnee — Garibaldi’s Description of the Mango Tree — Fresh Milk

from the CHAPTER V. (pp. 153-171)

Across the Straits of Bonifacio — Unwillingness of the Boatmen to go to Sea — Sail to the Maddalena — An English Officer’s Invitation to Dinner — His Excellent Wine and Interesting Conversation — The Wine of Sardinia — The Anniversary of Saint Andrew — Delayed by the “Tramontana” — The Captain’s Land Excursion — A Proposed Change of Route — Scenery in the Straits of Bonifacio — Last Sight of Caprera — Steering amid a Labyrinth of Small Islands — Loss of an Italian Frigate on the Lavezzi — Exploits of the Marquis of Bonifacio — The Monuments of a Great Name — Speculations on the Destiny of Corsica and Sardinia — The Resources of Sardinia — Proposed Railway from North to South — Spaniards in Sardinia

from the CHAPTER X. (pp. 306-308)

The Attractions of Sardinia

CHAPTER I. (pp. 27-35)

Secure a Passage for the Maddalena – On board the Umbria – Capraja – An Italian Professor – Capo dell’Orso, and other Islands – Arrival at Caprera

Secure a Passage for the Maddalena

I soon learnt at Leghorn that to reach my destination I must wait the arrival of the packet-boat, which sails once a week between Genoa and Porto Torres, in Sardinia, usually calling at Leghorn on a Friday morning. Therefore, on the first Friday after my arrival, I went at an early hour to the bureau to secure a passage for the Maddalena, the nearest island to Caprera. The answer was, “This passage should have been secured earlier, and too many tickets have already been issued.” I replied that my business was urgent, and that I could not wait a week; for the vessel goes only once a week to the Maddalena. I went then to some neighbouring Italian, who had been courteous to me the former day, and I persuaded him to use his local influence.

The result was that a passage was granted to me.

I then hired a boat to meet the Umbria. We waited a little distance from the shore the arrival of that vessel, and in a short time were nearly surrounded by other boats, heavily laden with the humblest class of people, who were evidently awaiting the arrival of that weekly packet boat, for which we also were on the look-out.

On board the Umbria

That vessel having at length arrived, we all went on board, and were soon followed by many others. Indeed, there seemed to be no end to the people anxious to sail with this small vessel. Each passenger presented his ticket before walking on deck, and, as I subsequently learned, the number of these tickets amounted to six hundred. The air on deck was close, and the space for moving confined. I therefore went below, but the cabin being darkened, perhaps through the crowd above, I returned on deck. The steps, however, from the cabin were full of people, and not very passable.

The passengers were exclusively of the stronger sex, and three only out of the six hundred were entitled to first-class tickets. About a third of them seemed provided with fire-arms, while nearly all had knives, and baskets of provisions. But if weapons were numerous, shirts apparently were scarce; and as for the style of dress among this crowd of human beings, it might be said that long gaiters, tattered garments, and very broad-brimmed hats, or caps, were the prevailing fashion. After looking at them, I endeavoured to divert my thoughts from the repulsive poverty of man to the attractive charms of Nature. I gazed at the lofty Apennines, blue in colour, save where whitened by the snow of winter.

Meantime the vessel was moving away, like a topheavy coach laden with passengers. One hundred and fifty were to be put ashore at Bastia, in Corsica, while most of the remaining number were to be landed at Porto Torres, in Sardinia. It lay deep in the water, and occasionally fell to one side. However, after a few hours’ cruise, to my surprise I found myself back at Leghorn. There nearly a third of our live cargo were thrust ashore amid cries of expostulation, and threats of protesie air amministrazione. My belief is that the captain, thinking it probable that the Umbria must either go downward or backward, had, after due consideration, decided in favour of the latter movement. Not only speed, but much fresh air, was gained by the vessel dropping nearly a third of its passengers at Leghorn.

Capraja

After leaving that port a second time, we moved freely through the wave, and in the afternoon approached Capraja, a volcanic island which rises abruptly from the sea. This island is grandly mountainous, and is inhabited by wild goats and fishermen. In November days are short, and as we sailed near Capraja, the grey twilight of evening was beginning to veil the lofty summits of its mountains. Soon it lay on the east of us. On the west rose Corsica, with its rocks vividly displayed under those glorious streaks of light with which the sun reddens the sky before he begins to bathe his golden car in the ocean. Bastia, to which the father of the great Napoleon migrated from Genoa, was the port at which our vessel was first to cast anchor.

An Italian Professor

Next day I rose early. It was about four o’clock when I paced the deck, and gazed at the long mountainous shore of Corsica, along which our vessel was sailing. Overhead were stars, by the light of which I could descry many bold promontories and indented bays. The deck seemed strewed with old clothes, nailed shoes, and odd-looking muskets. The muffled human beings, whose faces became more visible as the grey light of morning began to dawn, resembled the witches in the tragedy of Macbeth. Suddenly a person joined me in my walk, and surprised me by quotations from the Odyssey and other works. Finding, however, that I was English, he altered the style of his quotations. At length, when he saw the golden orb of day show itself in the east, he repeated —

“The sun is fair when he, with crimson crown And flaming rubies, leaves his eastern bed — Fair is this ocean, too, in crystal gown”.

What the next line was I do not remember, but my new acquaintance, who was a professor in the university at Sassari, presently darted off to Ossian, from whose works he quoted some lines of Cesarotti’s translation. He then spoke of the furnace in the sky, out of which the glowing orb of day was about to emerge, and brighten with its rays the towering peaks, and lofty outlines of the Corsican mountains.

Capo d’Orso, and other Islands

At the lower extremity of that island came into our view Capo dell’ Orso, This huge mass of granite is shaped fantastically, and the summit of it is like the figure of a bear. The celebrated author, Della Marmora, in his remarks about Capo dell’Orso, writes: “Ce roche offert cette ressemblance singulière, il-y-a près de deux mille ans; car Ptolémée, dans sa géographie, indique ce lieu sous le nom de ‘le promontoire de Tours.’ “It seems extraordinary that during two thousand years so little change- should have been effected in this rock by the atmosphere. Perhaps this long resistance to the hand of time may serve to prove the durability of granite.

Next after Capo dell’Orso appeared the isolated rock of the Cavallo, and then a ridge of rocks stretching far into the ocean, the Lavezzi, on which, during the Crimean war, the Sardinian frigate Semillante was lost with all her crew. Next came in view the steep and rugged island of Santa Maria. Presently rocky islands, and rocks too small to deserve the name of islands, formed a labyrinth through which our vessel, still heavily laden with human beings and their fire-arms, had to force its way. The Budelli and the Razzoli were among the largest of these.

No sooner had we passed these than the prow of our vessel went near Sparagi, an almost perpendicular island, which stood before us as if to bar our progress. […]

Arrival at Caprera

The luxuriant hills of the Maddalena, and the rocky islands of San Stefano and Caprera, together with the bold and gigantic mountains of Sardinia, formed that apparent lake into which our vessel had entered.

Soon piter arriving at the Maddalena, I hired a boat to take me to the General’s habitation. The narrow sea which separates these two islands is intersected with numerous rocks, which shoot up here and there; and as to the sunken rocks, they are said, with questionable accuracy, to be about three hundred in number. Save where it was whitened into foam by beating against some of these numerous rocks, this narrow sea appeared blue and transparent. Our boat glided rapidly over it, and in less than forty-five minutes touched the shore of Caprera.

CHAPTER II. (pp. 39 – 54)

Garibaldi at Home — The Wind at Caprera — On Board the Yacht — A Dangerous Channel — Garibaldi’s Seamanship — Tavolara — The Goats of the Island — Its Population — Extemporizing a Dinner — Sardinia — Night in the Gulf of Congianus

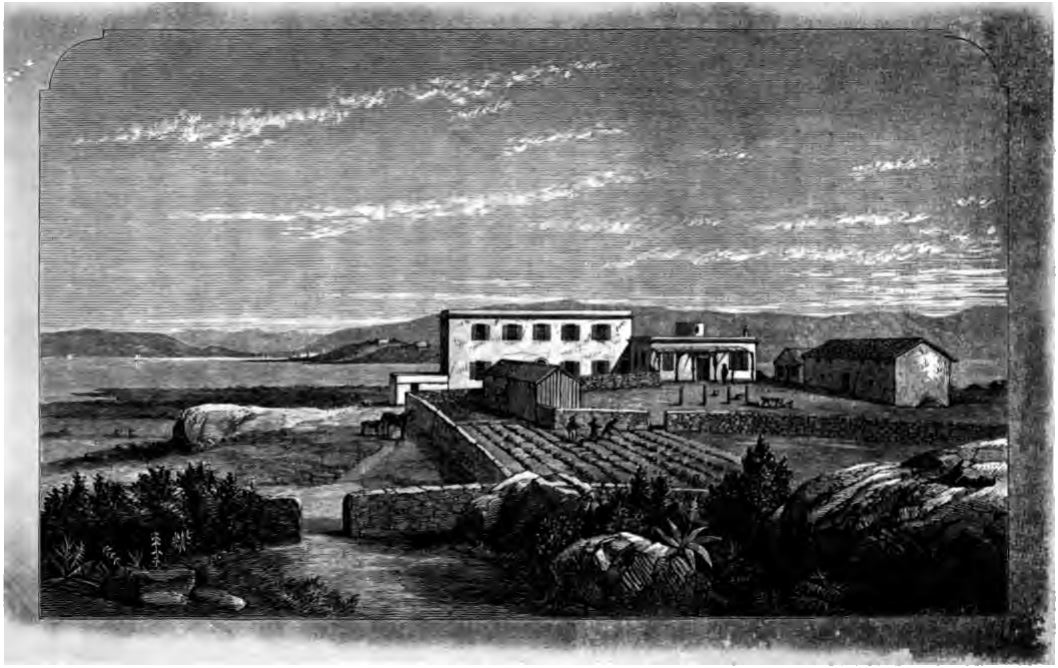

Garibaldi at Home

AFTER landing at Caprera, I climbed upwards amid rock and myrtle for about half an hour, and then I reached the great man’s cottage. I asked a servant in a red shirt if the General was at home, and in a few minutes I discovered he was at dinner. I wished to go away, but this was rendered impossible by Garibaldi requesting me to enter the room and partake of dinner. I was soon impressed with the belief that the General was not only the bravest of warriors and the purest of patriots, but also the prince of gentlemen. […]

There is not a post-office in Caprera, and although the post-office of the neighbouring island might have been safe enough for the transmission of letters on ordinary matters, I determined on not letting the General’s handwriting go out of my possession until I reached England. […]

The Wind at Caprera

In all the smaller islands near the Straits of Bonifacio the winds are said to be very vehement during winter. In the large island of Sardinia the high mountains serve as a shelter to many parts of the interior; but in Caprera throughout the year the prevalence of wind is such as to check the growth of trees. However, my experience arising from less than a fortnight’s sojourn under Garibaldi’s roof being small, I am induced to quote the following few lines from Mrs. Gaskell’s English version of the interesting little book entitled “Garibaldi at Caprera,” by Colonel Vecchj. The author says:

“I have often heard of the wind at Caprera. Elsewhere it may be a scourge — here it is a hurricane. This night it howled through the plants, laying them low.

The rocks re-echoed with the voice of the storm; the waves dashed furiously against the cliffs. In the Straits of Moneta, which are between Maddalena and Caprera, the sea is full of sharply-pointed sunken rocks, most dangerous in stormy weather. The quantities of wrecked boats to be seen among them are sufficient to prove the disastrous nature of the coast.”

This author, Colonel Vecchj, also relates that a month before he went to Caprera, Garibaldi, observing the distress of a Corsican captain, whose vessel was tossing about very unpleasantly among the rocks, had hastened to his rescue. Fortunately, with the exception of occasional gusts of wind, there was quite enough of calmness for me during my short but interesting sojourn under the hospitable roof of Garibaldi.

On Board the Yacht — A Dangerous Channel — Garibaldi’s Seamanship

The General had expressed a wish that we should be on board the yacht early on the morning of the 22nd of November.

There is such a mixture of dignity and mildness in his manner, that his wishes are usually interpreted as orders, and therefore most of us were on board the yacht even before the sun had begun to gild the neighbouring mountains. Fearful of being late, I ran down rapidly among the rocks and myrtle to the water’s edge, where Major Basso kindly rowed me to the yacht.

The position of the vessel was soon altered. The Sardinian mountains appeared behind us, and those of Corsica in front. We were for some time, between Caprera and Maddalena, in the midst of shoals, reefs, and rocks, with a strong wind blowing against us. Now and then the prow of our vessel was pointed towards a rock, as if to avoid some other rock either above or below water. The vessel ran on one of the rocks, and lost probably a little copper; but although the crew were new, we were soon off. I was busy asking questions about the numerous islands, when some one said to me, “Don’t speak — did you not feel it?” Then another person uttered the words, “Canale pericoloso, frequenti isole, &c.” — Dangerous channel, frequent islands, &c. I ascertained, however, that we were passing near Monte di Fico, a mountain where figs do not grow.

In clear tone, and with perfect knowledge of the sea, did this worthy descendant of sailors, Garibaldi, give his orders to Menotti, Riciotti, Basso, &c. Often did he call out, “Bada gli scogli!” — Mind the rocks! Then the General would turn to me, and with the courtesy which to him is natural, point out objects of interest, among which was one island inhabited only by wild boars, and another abounding in wild goats.

Tavolara — The Goats of the Island — Its Population

The latter of these islands, Tavolara, which rises two thousand three hundred feet from the water’s edge, seemed the more picturesque. It is very steep, and is said to be very difficult of ascent. That fine old sailor, Captain Roberts, told me at the Maddalena, a few days after this cruise, that he had reached the summit of Tavolara, but that he had found the ascent one of the most difficult experiments in climbing which he had ever attempted.

Della Marmora, who tried it in vain, relates the success of Captain Roberts, and adds, “Nous ne connaissons que fort peu de personnes qui soient réellement parvenues sur cette périlleiise cime.” The goats must therefore find the upper region of Tavolara rather a pleasant and safe retreat.

They told me on board the yacht that these animals have in that island teeth of an unusual colour. “Quasi d’oro” were, I think, the words which they used regarding the colour, and this tinge or colour of the teeth was attributed by them to the pasture of Tavolara. Such also is the opinion of Colonel Vecchj, from whose interesting little work I have already quoted. After describing a certain resinous tree of low growth, he says, “Perhaps it is to this plant, which is not to be found in any of the neighbouring islets, that the strange appearance of the herbivora in Tavolara may be attributed.”

Much would I have liked to have seen this scarce tree or shrub, and to have plucked its flower of blue petal and white calyx. Moreover, what I heard of the population of Tavolara rather excited my curiosity, and thus increased my wish to visit the island. It contains nearly half-a-dozen inhabitants, all members of one family, the founder of which died a few years ago. He belonged originally to the Maddalena, but he left that island on account of an error which he had committed there, in marrying his wife’s sister while his wife was still living. Being apprehensive of a want of harmony between the two ladies, who were sistersin-law as well as sisters, he deposited one of his wives in Santa Maria, and the other in Tavolara, and he visited them by turns. In consequence of this excellent arrangement he was blessed with two homes.

Of his two landed properties, that towering rock of the ocean, Tavolara, was the one which I most wished to see, and I indulged a hope that my wish would be realized, as the yacht continued for some time going in the direction of that island.

Meanwhile, the waves rose high, and our vessel bounded finely over them. They forced themselves occasionally on deck, and gave the General a bath, at which he laughed good-humouredly. Unfortunately, there are people in this world who have an occasional tendency to sea-sickness. Some of my fellow-passengers were sick, and in a sort of temporary desperation they uttered loudly the word “Muoia!” — May I die! Accordingly Garibaldi, who is one of the mildest of men, in deference, probably, to those who had not my bodily strength, put the vessel into the Gulf of Congianus, which is situated northward of the Golfo degli Aranci, or bay of oranges, and is separated from it by a ridge of hills or mountains.

Extemporizing a Dinner — Sardinia — Night in the Gulf of Congianus

On the 24th of November we lay at anchor in a gulf, with the wild shore of Sardinia on either side of us. The boat first landed us, and afterwards one or two servants with our cooking materials.

“Pick sticks for a fire,” said Garibaldi to myself and others. So, climbing up amidst the rocks and thick bush, we soon collected materials for a fire. A major, who had fought for the liberty of the Two Sicilies, extemporized an omelette, while some picked salad, and others went shooting. Sardinia abounds in game, but not in people, and the number of murders, which is computed at three thousand per annum, may aid in checking an excess of population. Private property belongs chiefly to Spaniards. The country is not much intersected by roads, nor restrained by laws. The natives are rather a wild set, but the first day we saw none of them.

When dinner was ready the General remarked to me: “This is what you call pic-nic in England?” I answered, “Yes, General, and on a grand scale.” At this pic-nic the rocks were our seats, and the blue sky was our ceiling, while towering mountains on the one side, and the blue Mediterranean on the other, were the ornaments or decorations of our dining-room. Garibaldi and his brothers- in-arms composed the chief part of the company. It was a dinner au naturel, to which both the greatness of man and the grandeur of nature helped to give interest. As for the gilding of an Italian sunset when evening was approaching, it was immeasurably beyond anything which poor art could rival in ornament.

As soon as twilight had succeeded sunset, we went on board the yacht again. Night came, and we retired to our cabins for rest. […]

I left my cabin a few hours afterwards. It might have been about four o’clock when I was pacing the deck of our vessel, which lay at anchor in the Gulf of Congianus. There, amid the silence of night and the solitude of Nature, I looked around me. Above me was the starry vault of Heaven; on either side of me were the mountainous shores of Sardinia. […]

Chase for a Sard — A Sardinian Cottage

After we had taken coffee, a boat was sent ashore full of people and firearms. I went in it, tempted by the love of grand scenery, and the desire, if it were possible, to catch a Sard. Six or eight hours had been spent the former day in the island without seeing a native or anything like the abode of man. This had so warmed or quickened my curiosity, that I resolved, though I might tear my clothes with the shrubs, or cut my feet with the rocks, to catch a Sard. His language might be a mixture of Latin, Italian, and Spanish, and therefore not very edifying. It would at least be new to my ears.

Meanwhile, the rocks around me echoed with the report of firearms. One sportsman, however, joined me, and we climbed the rocks together. The sole of his shoe gave way, my clothes were rather torn, the mountains seemed to rise higher, and yet not a Sard was in view.

At length we came to some goats, and a woman without shoes or stockings. Both herself and my companion were good-looking. They understood each other. Fortunately the Sardinian spoke Italian a little, and she told my companion, “Andar diritto e trovar una casa.” Such being our instructions, we followed them till we came to a rocky defile and a cottage. Here rushed out two enormous dogs, growling and thundering. They eyed us evidently as two suspicious-looking foreigners. Then a woman invited us to enter her dwelling. It consisted of one room only, and the earth was its floor. In the centre of it a fire of wood was burning ; but there was no chimney, and the door remained open to let the smoke escape. On one side of the room were ranged three small beds, while in a corner of it was a donkey, and also a large stone for pounding corn into flour. The children were almost without clothing. The woman brought us a wooden bowl of milk, with two wooden spoons, and presently she asked us the name of our king.

We spoke to her in reply about our excellent Queen Victoria, but she understood us not. We then told her we had come in the yacht of Garibaldi, and her eye beamed brightly. If a flash of lightning had passed through the room, the effect could not have been more instantaneous. Such in this remote cottage was the magic influence of true glory.

” Are you under Garibaldi ?” said she.

Though to be under him might be to go where “fas et gloria ducunt,” yet I was obliged, in answer to the Sardinian woman, to explain that we were only admirers of Garibaldi, and not followers.

After a short rest in the cottage, we commenced our descent, scrambling downwards amid rock and shrub, with our clothes and our shoes not in any way improved, till we reached the sea shore, where we found the dinner nearly ready. […]

The sky was starry, and there was just light sufficient to clothe rock and shrub, mountain and ocean, with a sort of mysterious grandeur. The Gulf of Congianus is indeed a convenient place for anchoring a yacht to those who love wild scenery, and the liberty of roving over lands which seemed inhabited almost by game alone. After walking about half an hour, I returned below, and found the General reading, which good example I followed. Then we had coffee. Soon afterwards the yacht began sailing, and the General, experienced captain as he is, was on deck giving his directions, and calling out, “Tira le vele;” “Ferma un poco;” “Vabbene;” “Passa indietro questa scotta;” “Fa attenzione,” &c. Riciotti steered.

As we moved onward, the scenery resembled a grand moving panorama, a rich store of beauty which Nature spread out to the eye. While I was engaged in admiring it, the sky reddened, and morning seemed to fling her rosy streaks over the Mediterranean. What glorious colours were then dyeing the summits of the Sardinian mountains, which, to our eyes, seemed interminable in their length!

In two hours we anchored about a mile from the island of San Sophia. Two of the boats went ashore, and the General’s daughter rowed one of them. The island is large, rocky, desolate, and uninhabited. We saw owls, but they were very shy. I was engaged picking up marble and stones perforated with coral, when our presence was desired on board ship, because the weather was becoming bad. Accordingly we returned on board the yacht, and soon after twelve o’clock we sat down on deck and partook of an abundant dinner. About an hour afterwards the General, who performed the duties of captain of a ship in a manner worthy of his old Genoese origin, sent Menotti in one of the boats for the purpose of sounding. In the course of the afternoon we passed a series of rocks called Perduti, notwithstanding the crew of a vessel lost there had saved themselves by swimming. Next we threaded a labyrinth of rocky islands, and then, after twisting to and fro, or tacking, we anchored in front of Caprera. We soon landed there, and, after half an hour’s climbing, found ourselves again in the house of the great and also hospitable Garibaldi.

Thus ended the first cruise of the yacht which English liberality has presented to Garibaldi. If the season of the year had been July instead of the last week in November, it might have been more favorable. If the crew which brought the vessel out from England had remained, it might have been more expert. If the soundings near Caprera were better, and the numerous sunken rocks more clearly defined in a chart, the navigation might have been more easy.

However, if the vessel could triumph over these difficulties, ride so bravely over the waves, and go through the sea at an average of seven knots an hour, she does indeed give fair promise of being most serviceable to her owner. Doubtless he could have had a fleet of yachts as easily as he could have either taken or accepted wealth and titles even before he had made a king of Italy. However, he has commanded self no less than he has commanded armies.

His island home is separate almost hundreds of miles from any continent. Many beautiful islands are within a short distance of it, but there is not a packet-boat from it to any of them. The noble inhabitant of Caprera, however, was the owner of a vessel called the Emma, but this vessel was unfortunately lost on its way from Genoa. After this event, the bestower of freedom and wealth upon countless thousands had few opportunities of leaving his own little barren island, until the good sense of some of his admirers, among whom is prominent the name of R n, suggested to them the propriety of sending him a commodious and well-built yacht from England.

CHAPTER III. (85-111)

The lentisk — Scio [or Kios] under genoese government — Revenue derived from gum-mastic-cause of the loss of Scio – Pliny on the healing powers of lentisk — Its value in the arts and manufactures — The Maddalena — Why Garibaldi fixed his Home in Caprera — Longevity in the Maddalena — Porto Pollo — The First House built in Caprera — Rape of the Women of the Maddalena — The Maddalena and Neighbouring Islands appropriated by Sardinia — Formation of a Naval Depot — The Roads of Agincourt — The Mountain Tejalone — Good Company while Reading— The Cavallo — A Flock of Bishops in Sardinia — Silence of History regarding Caprera — Capraja — Climate and Soil of Caprera — Cultivation of Cotton in Sardinia retarded by the Ignorance and Intolerance of its Inhabitants — Garibaldi’s Desire for the Increase of Commerce with England

The lentisk

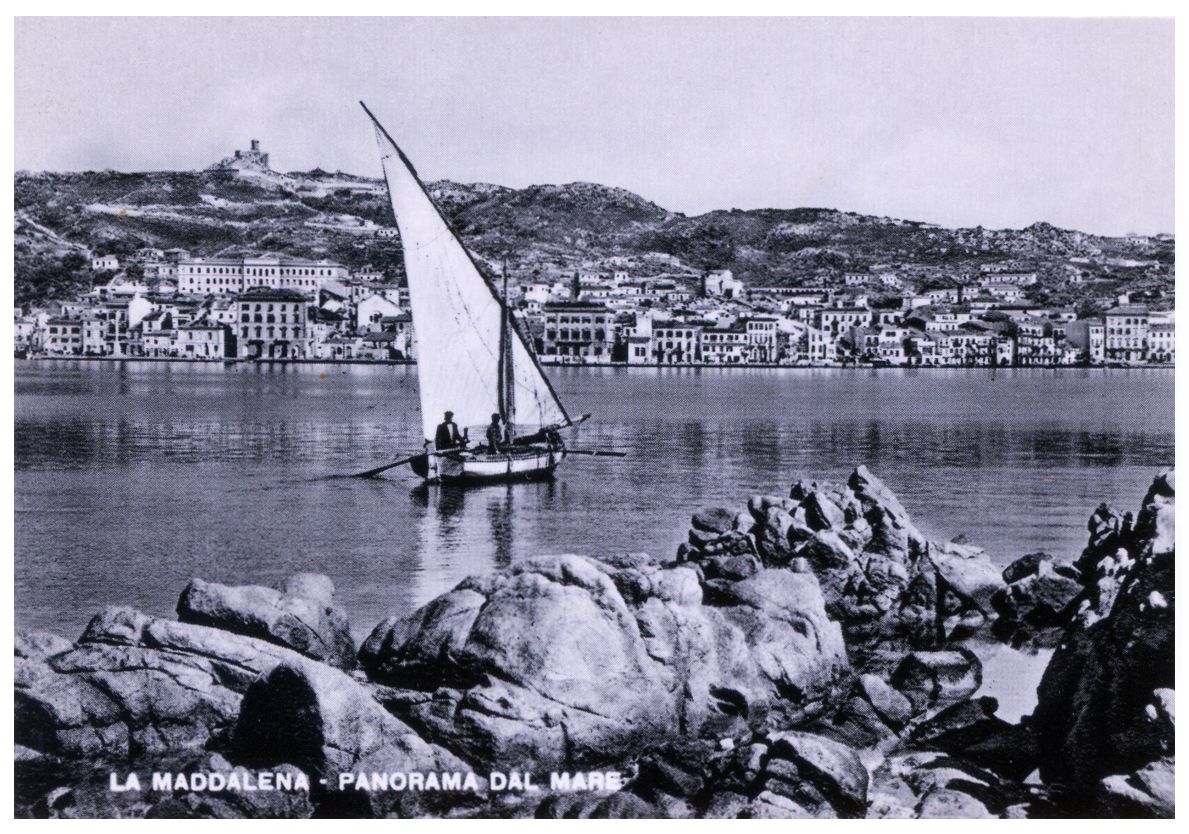

TURING my stay at Caprera, I made a few excursions to the Maddalena. It is much more cultivated than the former island, and yet it is hardly inferior to it in beauty. It is very rocky and hilly; but intermixed with rocks and hills are the vine, the fig, and the olive tree, and also thick bushes of myrtle, cactus, and lentisk.

With the first two of these shrubs I was familiar, as the myrtle grows in the open air in sheltered parts of England, and the cactus thrives in English greenhouses. But being neither a botanist nor a traveller, I regarded the lentisk as a sort of novelty.

What can this shrub be which seems to grow so abundantly in the Maddalena? was the question which I put more than once after walking over the rocky surface of that island. At length information was given to me that the lentisk was an evergreen shrub, which yielded a resinous substance known as gum-mastic. This recalled to my memory a part of the history of that country to which all Garibaldi’s ancestors belonged; for about two centuries ago, when Chios or Scio was a Genoese colony, the gum-mastic was a source of large revenue to the mother-country.

The sum of one hundred and twenty thousand ecus tTor, which that island paid annually to Genoa, arose chiefly from the tax levied on gum-mastic. But Chios or Scio was in those days almost as remarkable for its Christianity as its commerce. […]

It may also be said that in times when navigation was less understood than at present, Chios was more approachable than the Maddalena and Caprera, because the sea adjacent to it is less beset with rocks than that which surrounds the last two islands. […]

Pliny on the healing powers of lentisk – Its value in the arts and manufactures

After seeing so much of the lentisk near Garibaldi’s home, I turned to the page of Pliny’s work on Natural History, and felt an interest in his description of its healing properties. He states that its leaves, its wood, its bark, and its gummy or resinous matter are all useful. He tells a story of the daughter of a Roman Consul who was cured of a severe illness by drinking the milk of those goats which were fed upon lentisk. He mentions that lentisk is useful in curing ulcers, erysipelas, pains of the head and stomach, inflammation of the eyes, and various other diseases and ailments. In the list of ailments thus curable is one which excites much pain, together with little sympathy — toothache; and as there are persons who apparently have some dislike to extraction of their teeth, however skilfully that operation may be performed, either by the key or forceps, it may be desirable to know that the lentisk is highly beneficial to the teeth. The poet Martial has expressed a similar opinion in the following lines:

“Lentiscum melius; sed si tibi frondea cuspis Defuerit, dentes penna levare potest.”

Apart from its property of healing diseases whether slight or severe, the lentisk, which is indigenous to the Maddalena, possesses qualities which are useful in arts and manufactures. There is scarce any shrub which yields such good resinous matter as the lentisk; and that which grows in the Maddalena may be the more valuable in these days, because the best gum-mastic has not been obtainable in Chios ever since that island ceased to be under Genoese authority.

Its Turkish rulers will not permit the export of any gum-mastic to European countries except that which is of an inferior quality, while they reserve the superior quality for the decoration of buildings and other purposes at Cairo and Constantinople. But while Chios has ceased to be free, the Maddalena and some neighbouring islands have been relieved both from the misrule of Spain and from the incursions of African pirates.

It is therefore possible that the lentisk which grows so well in the islands near Garibaldi’s home, without being a source of much wealth, might prove at least valuable enough to reward private enterprise, and to increase the intercourse between England and some of the islands of Italy.

The Maddalena – Why Garibaldi fixed his Home in Caprera

The little town of the Maddalena, standing on an acclivity near the shore, and resting against a background of hills, appeared to me very picturesque. There is a large church in it, but to me it seemed rather in want of a congregation. However, it is not deficient in ornament, and among the valuable things which it contains are several presents from the renowned Nelson.

As to the priests, they are said to luxuriate at the Maddalena; and as to the laity, though not so bigoted nor so ignorant as their Sardinian neighbours, they are much attached to Papal authority.

Indeed, one day, when I was walking through the steep and rocky streets of the town with a layman, he complained to me that Garibaldi had irreverently called two of his donkeys Pio Nono and Antonelli; but it has not yet been my lot to see either these donkeys or their worthy godfathers.

One of the three English inhabitants of the Maddalena related to me some of the causes of Garibaldi’s fixing his home in the neighbouring island. The General informed her husband, whose brother has since become an eminent Queen’s Counsel, early in the year 1855, that he intended to live at Porto Pollo, in Sardinia. As Nelson highly appreciated the situation of that place for a naval station, it is possible that the maritime tastes of Garibaldi may have induced him to consider it too favourably for a place of residence.

It is said that during the months of summer and autumn Porto Pollo is subject to two kinds of fever — one of which kills the patient, and the other, which is of an intermittent character, is almost incurable. The English resident in the Maddalena, whom Garibaldi consulted, strongly advised him not to make Porto Pollo his home. He added,

“I am buying Caprera, and you can have part of it at a proportionate value, or, in other words, at the price which it costs me.”

With just and generous confidence in a man well worthy of it. Garibaldi concluded the bargain immediately. Caprera may be too well ventilated, but it is subject to none of the noxious influences which produce agues, fevers, and other diseases. The average rate of mortality cannot well be calplace which does not seem to contain so many as two dozen inhabitants, but in the neighbouring island of the Maddalena, where the soil and climate are almost the same as at Caprera, amongst a population of two thousand there are many instances of longevity.

Madame Schwarz records in her book some examples of old age which are rather extraordinary, and almost too romantic for an insurance company. While she was climbing up the rocks she met a gentleman coming down, who told her his name, and also his age, which was only ninety-eight, adding that his hair had been rendered gray by family affliction.

Longevity in the Maddalena — Porto Pollo — The First House built in Caprera

There are, however, many instances of long life at the Maddalena, and among them might be mentioned that of an honourable and intelligent officer of the British navy, who was in action fifty-nine years ago. Indeed, the climate of the smaller islands near the Straits of Bonifacio is said to be highly salubrious, and far preferable to that of Sardinia.

Nevertheless, the day may arrive when Garibaldi’s intended place of residence, Porto Pollo, may become not only healthy, but flourishing.

It is near [exaggeration, not much!] that majestic rock of Tavolara, which serves as a natural breakwater to this part of Sardinia, so that the numerous gulfs and bays which here indent its shores are well protected, and could well afford a secure refuge to fleets of vessels. They would also give facility in exporting the produce of a country which Nature has endowed largely.

But at present the shores of these gulfs and bays which face Tavolara are so thinly peopled, that the lands are untilled and the swamps undrained. These evils would probably vanish if the English engineer, Mr. Piercy, should succeed in making the projected line of railway from Ozieri down to this part of the Sardinian coast. If this railway should be completed, the situation of Porto Pollo would doubtless be improved. Meantime, it is not a desirable place of residence. Therefore it is fortunate that Garibaldi should have been induced by English advice to abandon his intention of settling at Porto Pollo, in favour of a place comparatively so poor and barren as Caprera.

Though toleration of all religions is an advantage which cannot be prized too highly, the Sardinians boast that no heresy has been able yet to spread in their island. Such being at present the bigotry of its inhabitants, it is probable that no part of Sardinia might have suited Garibaldi, who evidently has a great aversion to Popery. It is also probable that no other place could have suited him so well as Caprera. Yet before he came to live in this island it seems to have been very seldom chosen as a place of residence.

Indeed, Colonel Vecchj, in the interesting little work from which I have already made some quotations, states that the first house erected in Caprera was built about one hundred and fifty years ago, by a bandit from Porto Vecchio, in Corsica. However, he broke up his establishment in a few years, and went to Sardinia, where he found a better scope for his business; so that probably he may have at length scraped together sufficient money to pay for masses for the repose of his soul. After his departure from Caprera, there was never any fixed population in it until Garibaldi bought a portion of it, in the year 1855, from Mr. Collins.

Rape of the Women of the Maddalena

It is not easy to account for this absence of inhabitants, though all the islands near the Straits of Bonifacio may have been infested by pirates from Barbary, and thus rendered unsafe for habitation.

Even so late as the year 1812, a marriage party in the Maddalena was interrupted in the midst of its festivities by the landing of a large number of pirates. They knocked down the bridegroom, who lay for some time on the rocks insensible. When he looked up he could not find his bride, but he saw the vessels of the pirates on the smooth wave, with all their canvas spread, as the wind was favourable to them.

The sea was sparkling with the noon-day sun, and seemed even brighter than the shore. Presently it was discovered that almost all the ladies had gone upon a cruise. So decidedly were they preferred by the African guests, who may have had “a special license” for the occasion, that for a long time afterwards Maddalena was short of women. They were therefore obliged to send to Palau for ladies, because, as usual, the island of Caprera did not possess either man or woman. It is said that trade was not dull at that time between Palau and the Maddalena. On the contrary, it was remarkably brisk and lively.

The Maddalena and Neighbouring Islands appropriated by Sardinia — Formation of a Naval Depot —

Although this event in the year 1812 made a strong impression in the Maddalena, yet piracy had been on the decrease ever since the year 1767. In that year the viceroy of Sardinia, Des Hayes, sent against the neighbouring islands, or rather towards them, a small squadron, for the purpose of taking possession of them, in the name of the House of Savoy.

The men on board the royal vessels landed first at the Maddalena, which was then inhabited by a few shepherds, natives of Corsica. These peaceable men, instead of offering a useless resistance, were very glad to accept the protection of the invaders, who, in return for this good reception, built a fort for the safety of the islanders, and also left in it a small garrison. The squadron next proceeded to Caprera, where they encountered no resistance, as that island was then without an inhabitant. Their success was easy, and their triumph bloodless, with all the other islands.

By this annexation to the house of Savoy, in the larger island of the Maddalena, the number of people increased, and their habits were altered.

Shepherds soon gave way to agriculturists, and agriculturists in a few years to sailors. The first inducements to a seafaring life probably were the gain by fishing, and the profitable excitement of smuggling. A maritime taste grew up to such an extent, that few except old men, women, and children remained on shore. Thus in the great revolutionary war, when all Italy, except Sardinia and its tributary islands, fell into the hands of the enemy, the Maddalena became a great naval depot.

The Roads of Agincourt — The Mountain Tejalone —

But while the Maddalena became thus important, Caprera had no permanent inhabitants, and the cause of this difference in the state of the two islands may have been the innumerable sunken rocks which render Caprera difficult of access. It is at least certain that the ship of Nelson, rather avoiding that island, lay in the strait which separates the Maddalena from Sardinia, and which is called the Roads of Agincourt.

This channel is also quite enough intersected with rocks, and therefore the navigation of it is some-what unsafe, except to skilful pilots and experienced mariners. These rocks, however, were so far useful to the great Nelson, that he could remain behind them, perhaps unseen, or scarce approachable, if seen, and spy the movements of hostile vessels, as the channel commands a view of the open sea. The high mountain, which rises near the house of Garibaldi, Tejalone, also commands a very extensive view of the sea; and though it may not have been so used during the war against France, yet a few men might not have been uselessly employed in reconnoitring on its summit, and signalling or communicating with the English fleet, in case of necessity. […]

The Cavallo — A Flock of Bishops in Sardinia — Silence of History regarding Caprera

That little rock near Caprera, the Cavallo, too small even to be called an island, was known to the Romans merely as a quarry of the finest granite. The adjacent island of Sardinia, after the decay of its wealth, and the neglect of both its cereal and mineral resources, enjoyed a strange distinction. The reader of Gibbon’s immortal work,” The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire will remember that about the year a.d. 530, Sardinia became the abode, during fifteen years, of no fewer than two hundred and twenty bishops.

The neighbouring island of Caprera, however, got no share of bishops, which may appear somewhat unfair, because another neighbouring island, Corsica, enjoyed an honour similar to that of Sardinia, though to a less extent, as the flight of bishops towards it about the year a.d. 530, did not exceed forty-six in number.

In short, with the exception of its temporary occupation by a Saracen commander, who meditated an enterprise against the patrimony of Saint Peter, the name of Caprera is rarely mentioned in any history either of ancient or modern days.

The island of Caprera, besides being without notice in history, seems to have been, until Garibaldi settled on it, generally uninhabited, although islands of less dimensions are populous. Among these may be mentioned Capraja, which I passed on my way from Leghorn. It possesses about 2500 inhabitants, although it is much smaller than Caprera.

Climate and Soil of Caprera – Cultivation of Cotton in Sardinia retarded by the Ignorance and Intolerance of its Inhabitants.

Yet the latter island, besides having a very salubrious climate, is not without productiveness.

It is favourable to the culture of the vine, and to the growth of figs, olives, oranges, chestnuts, and several varieties of fruit.

Perhaps the climate and soil of Caprera may be also pronounced favourable to the growth of cotton, as a slight quantity of it was produced there not long since, and the quality was found excellent.

But even if it could be grown at a remunerative price in the island of Garibaldi, it is not probable that he would like to live in the midst of a colony of cotton-planters. However, there seems little chance of the searchers for wealth endeavouring to disturb the retirement of Caprera; for that island has few material resources, and possesses little aptitude for the pursuits of trade and commerce.

It is an island of steep and sharply-pointed rocks; but the flowers which grow among them are lovely, and the vines luxuriant, and the patches of grass in the hollows between the rocks are velvet like; while the streams which descend from the heights serve to fertilize some of these localities. The mountain which rises near the house of Garibaldi is lofty and commanding, like some model of human greatness, which rises above ordinary men.

The sea is usually stormy, and the waves which dash against the rock-boUnd sides of Caprera help to break its prevailing solitude. In short, for its beauty and grandeur this island is largely indebted to the gifts of Nature, and for its interest to the presence of Garibaldi.

Whatever may be Garibaldi’s opinion about the growth of cotton near his own abode, he is highly favourable to its cultivation in Sardinia.

He expressed to me his belief that cotton of excellent quality might be grown in that island. Three of the principal qualifications for the growth of that valuable plant are a certain degree of heat, a sandy soil, and vicinity to the sea. Besides having the last two requisites in many of its localities, the large island of Sardinia cannot be said to want the first of them, because the palm-tree flourishes in it, which tree cannot thrive where the solar influence is feeble. But the warming, nourishing, and invigorating effects of the sun are there neutralized by the chilling influence of bigotry and intolerance.

Although Sardinia does not, as formerly, belong to Spain, much of the soil still belongs to Spanish proprietors, who have used their utmost efforts, within the last thirty years, to prevent the introduction of the culture of cotton. In their ignorance and their prejudice, they thought that it would yield no profit. They also thought that it would interfere with agriculture.

However, the cotton is not sown until the months of March and April, and the gathering of the cotton harvest, or picking of cotton, rarely commences before October. Moreover, this light labour is easily performed by women and children.

Thus the interference of the cotton culture with the seed-time and harvest, and all the operations of the cornfield, is impossible. This truth may, in course of time, dawn on the minds of the Sardinians, and induce them to give the cultivation of cotton a fair trial. Meanwhile, it may be remembered that the best cotton is produced in countries where the soil, climate, and situation do not differ much from those of Sardinia, but where the state of the people is entirely the reverse of that of the Sardinians.

Thus, in the American state of Georgia, which produces some of the finest cotton in the world, there is perfect toleration; and though the majority of the people are Wesleyans and Baptists, all religious denominations are placed on an equal footing. On the contrary, in Sardinia the people are so rigidly attached to the Roman Catholic faith, that no other religion is tolerated by them; and, as already remarked, no heresy has yet been able to spread itself in their island.

Though there may be apparent absurdity in representing this spirit of intolerance as unfavourable to the culture of cotton, yet it is an historical truth that both the culture of cotton and the manufacture of its productions declined in Spain when the Moors were expelled from that country by their more intolerant adversaries — the Roman Catholics.

These reflections sprung from my conversations with Garibaldi, who informed me that he had remained fourteen years in South America, and also that be had lived in several of the cotton growing countries.

He resided for some time in the Brazils, where good cotton is produced, and where, though the established church is Roman Catholic, all other forms of Christianity are both tolerated and protected. The cotton of the Brazils, however, is far inferior to that which is grown about thirty-five degrees north of the Equator, especially in Carolina. There the climate somewhat resembles that of Sardinia; but so different is the religion of the people in these last two places, that Carolina is nearly void of Papists and Sardinia of Protestants.

All this seems well known to Garibaldi, whose knowledge both of men and countries is extensive. If, as he thinks, good cotton could be grown in the large island adjacent to his own, the freight or charge for transmitting it to England might, on account of the comparative shortness of the voyage, not be expensive.

Soon after this conversation with me about Sardinia, Garibaldi told one of his guests that he considered that island better adapted to the growth of cotton than the territory of the Two Sicilies; which remark called to mind that both these fine territories have been wasted at different periods of time, that of the two Sicilies under the iron sway of Spanish Bourbon kings, and that of Sardinia under the bigoted rule of Spanish viceroys.

Garibaldi’s Desire for the Increase of Commerce with England — Chutnee — Garibaldi’s Description of the Mango Tree — Fresh Milk

My conversations at Caprera with its noble owner have given me the opinion that he likes England next after his own country, and that he would rejoice at a largely increased export, whether it were of silk, cotton, wine, oil, or any other produce, from Sardinia or any part of Italy to England, because this increased export, by rendering the ties closer, and the intercourse more frequent? between the two countries, would tend to increase the liberty and promote the welfare of his own.

Before my visit to Caprera the character of Garibaldi had appeared to me as a shield to the oppressed and a mirror of truth. I had not been long under his roof before he reminded me of a book of knowledge.

One day, soon after twelve o’clock, when we were at dinner, and after I had just finished a plate of excellent minestra, some of the Italians asked information from me about certain bottles of sauces which an English yacht-possessing noble* man had left at Caprera. Perceiving that one of these bottles was marked Chutnee, I remarked that the mango was amongst its ingredients. Garibaldi immediately said, “I have often seen the mango-tree in the Brazils, India, China, and other countries.”

He described the great height to which it grows in many places, together with the rather glossy appearance of its leaf, the yellow colour of its flower, the size of the nut and kernel, and many particulars, all of which to me, who had not been in any “part of the tropics, was both new and interesting. He also described some of the other products of the Brazils m a very pleasing manner, and then he narrated a few of his adventures while warring in that country.

As soon as there was a pause in the conversation, I prevailed on some of the Italians who were sitting near me to try the Chutnee sauce; but they soon appeared to have had quite enough of it, and one of them vowed be would not taste it again unless, in case of illness, it was prescribed for him by his medical attendant. As for myself, I required no sauces at the General’s hospitable house, so palatable without them were the abundant repasts of dinner and supper. The last two were so like each other, that I could have thought I was dining twice a day, if the supper of meat, fruit, wine, &c, had not been accompanied by tea, which, with the General, is a favourite beverage.

The colazione was at nine o’clock in the morning. How excellent then was the fresh milk! If good milk be the test of good cows, the patches of long grass at Caprera must afford good pasturage for cows.

Perhaps there are not two houses in Caprera, and as the number of cows which belong to Garibaldi is not less than one hundred and eighty, there is no necessity, on the ground of an insufficient supply, to dilute the milk with water, after the fashion of some great cities. In large towns it sometimes happens that cattle are maintained in places which are almost without air and light, and which seem little better than Roman prisons.

At Caprera the animals, whether cows, dogs, or horses, are generally free to rove, and are always treated by their noble owner with a gentleness to which the subjects of some rulers, or mortal gods on earth, as Lord Bacon has called them, are unfortunately strangers.

from CHAPTER IV (pp. 151-152)

Departure from Caprera

In front of me were the rocky islands of San Stefano and the Maddalena. To the north were the mountains of Corsica, of an -azure blue colour, except where whitened by snow, and to the south were the dark and gigantic mountains of Sardinia. Not far off lay at anchor the yacht which had lately conveyed me to one of the most interesting of picnics. The mountain air was pure, and the moral atmosphere untainted. With the thoughts of pleasures unalloyed still fresh in my memory, I hastened down to the boat which was to convey me to the Maddalena, and very soon ceased to tread the island of Garibaldi.

CHAPTER V. (pp. 153-171)

Across the Straits of Bonifacio — Unwillingness of the Boatmen to go to Sea — Sail to the Maddalena — An English Officer’s Invitation to Dinner — His Excellent Wine and Interesting Conversation — The Wine of Sardinia — The Anniversary of Saint Andrew — Delayed by the “*Maestrale” — The Captain’s Land Excursion — A Proposed Change of Route — Scenery in the Straits of Bonifacio — Last Sight of Caprera — Steering amid a Labyrinth of Small Islands — Loss of an Italian Frigate on the Lavezzi — Exploits of the Marquis of Bonifacio — The Monuments of a Great Name — Speculations on the Destiny of Corsica and Sardinia — The Resources of Sardinia — Proposed Railway from North to South — Spaniards in Sardinia

Across the Straits of Bonifacio — Unwillingness of the Boatmen to go to Sea — Sail to the Maddalena

I HAD hired a boat, with two sailors, to take me across the Straits of Bonifacio to the town of that name, where I could pross the mountains to Bastia, and from thence easily reach Genoa, It was Wednesday, and I had adopted this unusual route to save nearly a week’s delay, because the steamboat for Genoa, as a rule, sails only on Tuesday. While we were sailing to the Maddalena, however, the men whom I had hired to take me to Bonifacio wished to delay crossing the straits to Corsica, representing that the contrary wind which was blowing, the *Maestrale, the bad weather, and the rough sea, would render the passage worse than tedious. “Dubbio anche della vita!” exclaimed one of them.

[Note. “Maestrale” replaces “Tramontana”, which is an obvious slip of the writer McGrigory]

I did not know whether these men were sincere, but I felt dependent on them. I was conscious also that, if I insisted on their performing their engagement, they might at least, after beating about for some time against the wind, run the vessel into some creek or gulf which I did not intend to visit, and thus cause me a loss of time and money. On the other hand, I did not like to wait till the next vessel started for Genoa, and I was equally unwilling to solicit the loan of the yacht to take me to Bonifacio. My forced inactivity at that moment convinced me that the situation of one inhabiting any of the islands in these waters without a yacht must be worse than monotonous. Fortunately, on reaching the Maddalena, I discovered that the weekly steamboat to Genoa had been detained there by bad weather, and that it was the intention of the captain to sail in about six hours. Accordingly I engaged my passage immediately by this conveyance.

An English Officer’s Invitation to Dinner — His Excellent Wine and Interesting Conversation — The Wine of Sardinia — The Anniversary of Saint Andrew

About a quarter of an hour after landing at the Maddalena I received a polite invitation to dinner from an officer who had served under Nelson at the battle of Trafalgar. His soup he said would be ready some time before the steam of the packet-boat for Genoa could be up, and accordingly I had no hesitation in availing myself of his hospitality.

Moreover, that keen north wind, the *Maestrale, which was then rather violent, though unfavourable to sailing, is very favourable to appetite. I hastened, therefore, to the house of Captain K., where I was kindly received. An English lady of good birth, and of well-stored mind, together with Susini, was present at this dinner-party.

Our host the captain, after the war, had been the intimate friend of Byron, Shelley, and other distinguished men; while in the subsequent years of his seclusion he had been an intense reader. His conversation, therefore, was interesting. His wine also was good, especially the Sardinian.

Sardinia may not be now the same fertile country which it was in the time of ancient Borne; it may no longer be a granary propensce Cereris; it may not be, as Polybius has described it, “magnitudine et – multitudine hominum et omnium fructuum excellens.” Nevertheless I know on good authority that Sardinia does produce excellent wine.

During dinner I acquainted the party that the day on which I had the pleasure of dining with them, the 30th of November, was the anniversary of the patron saint of Scotland. The result of this information was that the Italian and the two Saxons united with myself in doing honour to the memory of Saint Andrew.

Delayed by the “*Maestrale” — The Captain’s Land Excursion — A Proposed Change of Route

[[Note. “Maestrale” replaces “Tramontana”, which is an obvious slip of the writer McGrigory]]

In the afternoon I went on board the steamboat, being aware that steam renders vessels rather independent of contrary winds. The Maestrale was still blowing strongly, and the sea appeared agitated. Our vessel, which faced the picturesque town of the Maddalena, was to sail in the course of the evening; but to my surprise, when I came on deck in the morning, it was still in the same position. I asked the cause of this delay, and the answer was, The Maestrale. About nine o’clock I understood that the captain had gone ashore. I asked why he had left the vessel, and the reply was summed up in the word Maestrale. As it was more than probable that the ship would not sail without the captain, I went ashore, and there learned that he had climbed up the hills. I asked the reason why he had done so instead of ordering his vessel to sail, and the only response I received was couched in the word Maestrale.

The sea, in short, had been roughened by that wind, and the captain had taken a long, steep walk, not to see how the land lay, but the ocean.

As the difficulty of going northwards, whether by hired sailing vessel or by steamboat, with a strong Maestrale wind, seemed great at the Maddalena, I began to think of setting out for Porto Torres, in Sardinia, where I might find a vessel going either to Marseilles or Genoa. I could sail from the Maddalena to Palau, in Sardinia, a distance of only three miles; and from Palau, with the aid of Sardinian ponies, I could reach Porto Torres in two days.

As my baggage, however, which had become bulky, was very precious to me, abounding in relics of Caprera, and containing presents from the noble inhabitant of that island, I would not incur the chance of losing it by leaving it at the Maddalena, or by taking it into an island like Sardinia. I had thus no alternative but to wait the return of the sea-captain from his land excursion.

When the captain at length returned from his walk, he began to think seriously of commencing his voyage. We hastened, therefore, on board the steamboat, which for some days had been lying at anchor in a sea to which the islands almost surrounding it gave the appearance of a Scotch lake.

Scenery in the Straits of Bonifacio — Last Sight of Caprera — Steering amid a Labyrinth of Small Islands — Loss of an Italian Frigate on the Lavezzi

As I might never again be in this part of the straits of Bonifacio, I gazed with great interest at the scenery, to which the diversity of rock and mountain, shrub and vine, imparted a character both of wildness and beauty.

The abodes of men were not numerous, but they were interesting. Nearest to me was the house of that intelligent, true-hearted, and gallant Englishman who had borne no mean part in Nelson’s victories. Not far off, and still plainly visible, was the house of that ex-dictator and patriot, to whose unblemished character Plutarch, if he had lived in these days, might vainly have sought a parallel. Caprera, his home, soon began to fade from my view, but not from my memory.

The panorama of islands, with a channel rather winding, and a sea rather stormy, came next. Among the numerous rocky islands were the Budelli and the Razzoli. The island of Spargi seemed like a barrier of rock in front of us. Very often the prow of our vessel was pointed against one rock in order to avoid another. Amid this labyrinth did the skilful helmsman) steer our bounding vessel, till we approached the bold promontory at the southern extremity of Corsica. Nearer was the Cavallo, and nearer still that series of rocks, the Lavezzi.

Possibly the Italian frigate which a few years since foundered on those rocks, with the loss of a thousand persons, may have been blown against them by the Maestrale. I thought of the disappointment occasioned to me by that wind when I looked from the deck of our steamboat At the rock of Bonifacio, which Nature has made grand, and history has rendered interesting.

Exploits of the Marquis of Bonifacio — The Monuments of a Great Name — Speculations on the Destiny of Corsica and Sardinia

As far back as the year 830, an Italian Marquis, named Bonifacio, after gaining a victory over the Saracens, landed near the southern extremity of Corsica, and built a castle on an impregnable rock. A town sprang up below, and, as a memorial of the Marquis’s exploits, the rock, town, castle, and sea were all called by his name. Straits of Bonifacio! whose waves are now ruffled and swollen by a wintry storm — rock of Bonifacio! whose lofty head is now veiled by a wintry cloud (said I, before they faded from my view) — you are worthy monuments of a great name, and even eloquent proofs that, unlike perishable riches, true nobility will survive all the vicissitudes of fortune, and live through the lapse of ages. Gladly would I have visited the town which bears the name of that Marquis who a thousand years since humbled the enemies of the Cross; but I was without leisure, and had not even a boat of my own on this occasion to contend against the obstacles of that vexatious wind, the Maestrale.

That contrary wind, to which I have already made allusion, detained our steamboat some time within sight of the Straits of Bonifacio. The genius loci accordingly prompted me to speculate on those two islands, which are divided by only seven miles of ocean, though my thoughts ran chiefly on the one which I had lately visited. Within the last seventy years, how different has been their political destiny.

During the lifetime of the great Napoleon, the first Italian possession which fell into the hands of France was Corsica, and subsequently nearly all Italy became French, except Sardinia. Though both islands are more or less neglected, yet the former, under French rule, seems to have made the greatest progress hitherto; while the latter possesses the greatest resources.

The Resources of Sardinia — Proposed Railway from North to South — Spaniards in Sardinia

An intelligent Genoese informed me that the soil of Sardinia is exceedingly favourable to the production or cultivation of corn, wine, oil, flax, silk, and cotton, that some of the forests of the island abound in cork-trees and excellent oak, and that its mines are rich in iron, silver lead, and copper.

If the want of roads be an obstacle to the enjoyment of that wealth which this fine island once possessed, and which Nature seems to have intended for it, the Italian Government appears recently to have adopted an excellent expedient for overcoming this obstacle.

I learnt first in Caprera, and afterwards in Genoa, that an English company had obtained from the Italian Government highly favorable terms for the construction of a railway almost from one end of the island to the other, from north to south, from Porto Torres to Cagliari.

Although a large part of Sardinia belongs to Spaniards [sic. – so, but that’s not correct!], who are inimical to religious liberty, and also to improvement, yet much belongs to the Government, which has ceded to the company 480,000 English acres in perpetuity.

The Italian Parliament has voted to it an annual income, for 99 years, of £580 per mile of railway, or a total sum of £139,200 per annum, in case that the whole of the intended line of railway, involving an extent of 240 miles, should be constructed.

It is, therefore, to be hoped that under the enlightened policy of the House of Savoy improvement may at length advance into Sardinia — that the truth and liberty which shine in the neighbouring little island of Caprera may soon dawn upon the haunts of superstition and ignorance — and also that British industry may develop those resources which in one of the finest islands of the Mediterranean have been for centuries lying useless. These are objects greatly to be desired, even though, in order to secure them, some of the religious houses should have to be suppressed.

While I was thus meditating on Sardinia, the whole island receded from my view, but not from my memory. Those dinners on its wild and solitary shores, and beneath its lofty mountains, were not to be so easily forgotten. […]

CHAPTER X. (pp. 306-308)

The Attractions of Sardinia

Thus ended my excursion to Caprera, which to me, at least, was full of interest. The grandeur of Nature did not seem at all impaired by the dreariness of the season. The scenery, on the contrary, was sometimes rendered more attractive from being dressed in the wild garb of winter. The principal charm was in the variety of aspects which Nature presented. Amid the winding valleys of the Jura mountains, in Burgundy, and on the frowning precipices of Savoy, she seemed to me gloomy in her attire; while in the Alps her giant limbs were covered with a robe of snowy white, which south of the Apennines she changed for one of gay embroidery. At Nervi, and other parts of the Riviera di Levante, near Genoa, where groves of orange trees were putting forth fruit, flower, and leaf together, “she seemed drest in gay enamelled colours mist.” The rocks in the Mediterranean were like gems to her robe of azure blue, especially those numerous rocky islands which guard the approach to Caprera, the fragments of pink and red coral tossed on whose shores were indeed no mean ornaments. In the neighbouring island of the Maddalena, the cactus and Moorish fig, together with many other shrubs and trees, were objects pleasing to the eye.

Southward of the rock-bound Corsica, whose blue-looking mountains, with their snowy summit had often attracted my notice, lies that island where gardens bare lapsed into deserts, and when a population of more than six millions has decrease to about half a million, but in which, spite or neglect and all the defects of former misrule, Nature still in many places luxuriates amidst figs apples, and grapes, together with orange, lemon and citron trees, and where beech, cork trees, find oaks, and even stately palms still flourish.

Sardinia has special attractions for travellers of very different tastes and pursuits. To the tourist, she offers in a variety of delightful scenery; to the sportsman, an abundance of wild ducks, wild boar wild hog, deer, foxes, and other kinds of game; to the agriculturist, a rich soil and a highly favour able climate. Agriculture is still in a very primitive state in Sardinia. Windmills are unknown and even spades are scarce. The scanty implements of husbandry are of the rudest kind. I short, Sardinia has been richly endowed with the gifts of Nature, but the low price at which land may there be purchased shows that those gifts ye remain to be appreciated. It seems strange that one of the finest islands in the Mediterranean should be less known than some of those in the Chinese seas; although a journey from London to Porto Torres need not occupy more than six days. This, however, is by the way.