From Bonifacio to Santa Teresa Gallura

It is a tribute to the easy way they have of doing things in France that on the morning of my departure from Bonifacio I forgot entirely about getting my passport stamped. In Italy, on the other hand, one has such matters constantly upon one’s mind, and indeed the police and their regulations are a perpetual source of disquiet to the foreigner.

The rain was pouring down in torrents when I reached the quay with my baggage. In the café facing the little Italian steamer, the Gennargentu, which was to carry me across the straits I found the Dutchman and the Swede. They too were bound for Sardinia!

It was the Dutchman who reminded me about my passport, and in some alarm lest the steamer should start without me I hurried off through the rain to interview the Commissaire de Police. I need not have been scared. The Gennargentu was in no hurry to leave.

The little boat was neat as a new pin, clean and smart and freshly painted. As it was too wet and too windy to stay on deck, the Swede, the Dutchman, and myself — the only passengers-forgathered in the saloon. As soon as we emerged from the harbour into the open sea the boat began to roll uncomfortably, and depression overcame the three of us. We were not seasick, only thoroughly miserable, and feeling, like Cardinal Newman, far from home.” There seemed to be nothing obtainable on the ship that would cheer us up, but suddenly I remembered the bottle of Hennessy which I had in my suitcase. I unpacked it, managed to get three thick tumblers from the steward, and issued a bumping ration of brandy to my companions and myself. The Swede accepted his with that mixture of mock reluctance, real pleasure at getting something for nothing, and dark suspicion of the motive that might possibly be under-lying the gift with which my experience of his type had made me familiar. The Dutchman swallowed half his glass at one gulp, so that his eyes nearly bulged out of his head; both of them became comparatively talkative.

They were sailing the next day by steamer from La Maddalena to Terranova [Olbia]. From Terranova they were going on by train to Sassari and Cagliari. “Two or three days,” the Swede thought, would be quite long enough time to enable him to “see the island.”

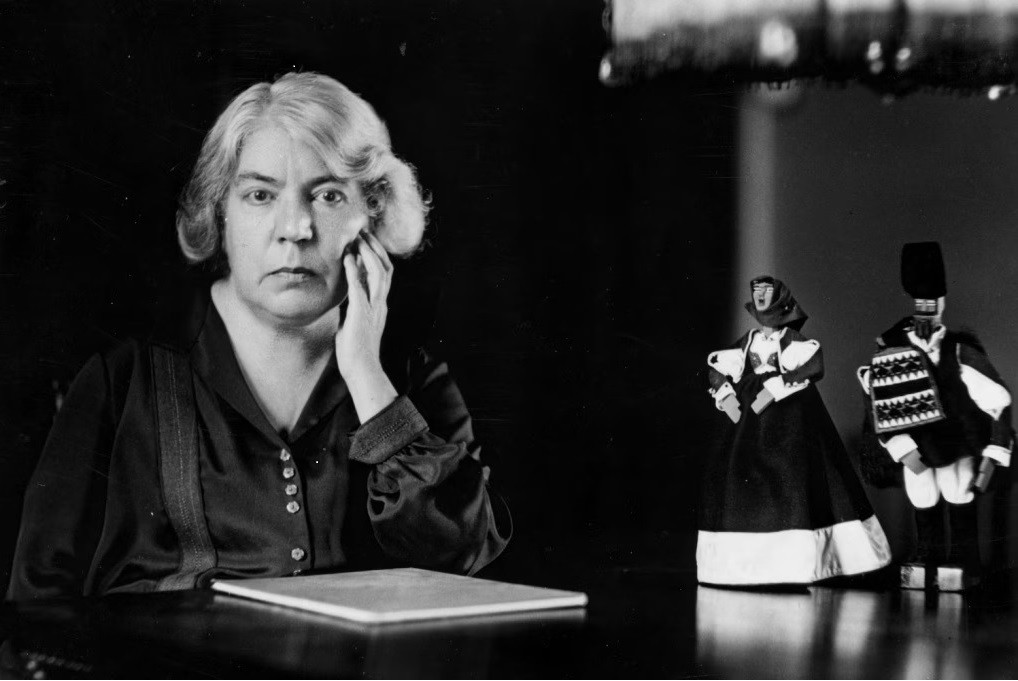

We began talking about Grazia Deledda and her novels of Sardinian peasant life and about the Nobel Prize. I mentioned casually that a good many English people wondered why Thomas Hardy had not been honoured. But the Swede crushed me by saying that the learned body in Stockholm which awards the prize envisaged the whole of the world’s literature with strict impartiality. Mere fame, national or international, did not affect its judgments.

I asked him if he thought that the recent developments in the Tavolarian drama were receiving adequate attention from the Swedish Academy. For a moment I feared that he too might have been reading a guide to Sardinia—Tavolara is a small island off the coast, near Terranova, inhabited in the last century by one family only, whose head was playfully given the title of ‘king’ by Charles Felix. SI but evidently he had not done so, for he informed me, gravely, that a learned Professor Smellfungus had for many years past made a special study of the Tavolarian stage. I need have no fears upon that score. Nothing I in art, literature, or the drama could escape the all- seeing eye of Stockholm.

The weather had not improved, but though there was more wind, there was less rain. We finished the bottle between us, and, heartened by the cordial spirit, I climbed up on deck and looked at the dark, grey, rocky coastline toward which we were fighting our way. How bleak and Northern it looked! Not a tree was visible anywhere. We might have been approaching the east coast of Scotland or the west coast of Sweden. I was standing just in front of the captain’s cabin. Immediately behind me was a brass plaque with the profile, in relief, of Mussolini at his grimmest, and underneath it the Fascist motto: Adversus hostem a terna auctoritas esto. I knew from this that already I was in Italy. Something of that æterna auctoritas, centralized in the Duce, inspired even the little Gennargentu.

SANTA TERESA GALLURA

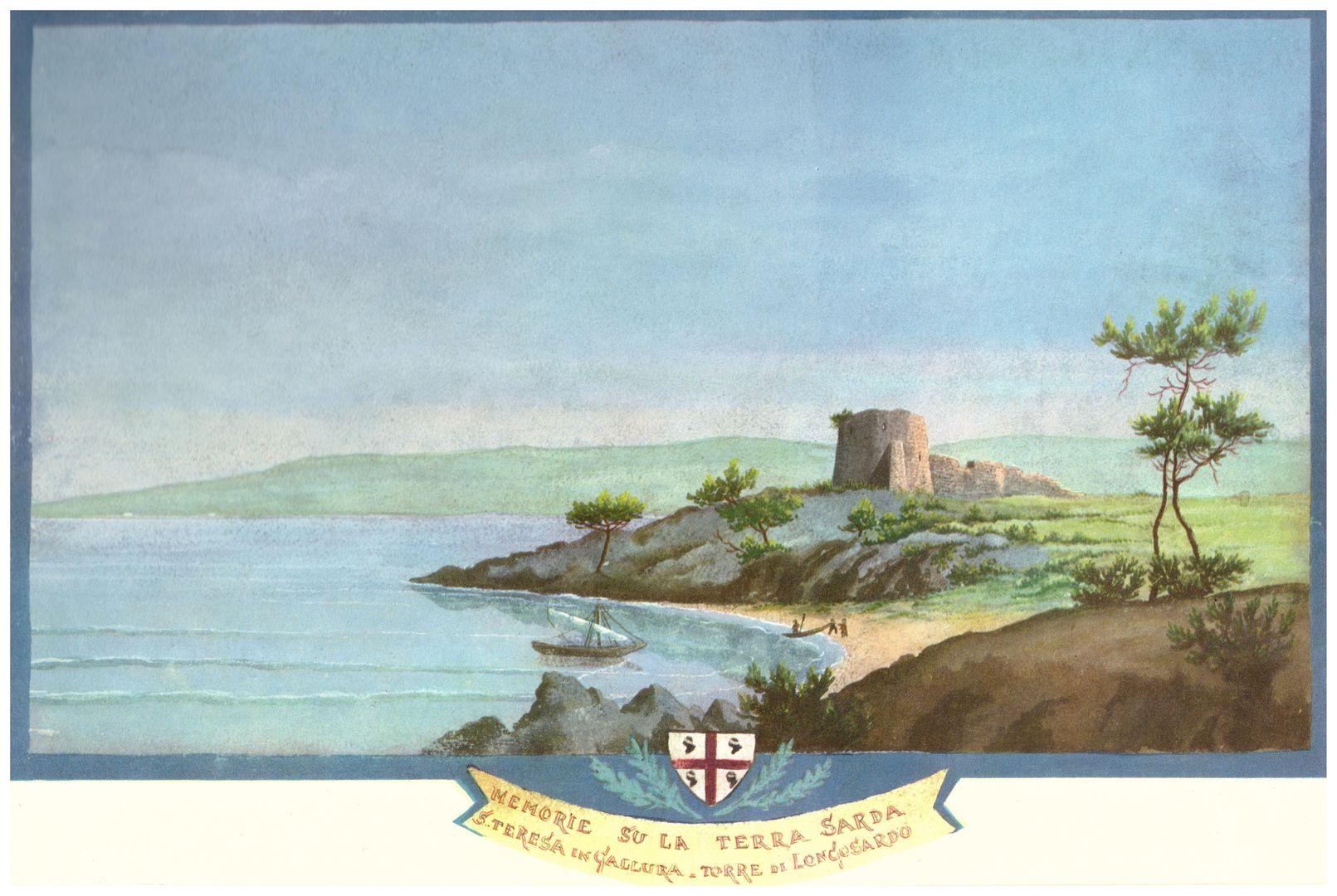

As we approached Capo Testa, on which stands the old round tower of Longon-Sardo, the houses of Santa Teresa Gallura, our first port of call, came clearly into view.

The village is built on a bare, grassy plateau, above a narrow creek. In the background is a line of low granite hills. It is treeless, shadeless, unprotected from either sun or wind; and in the stormy twilight under the grey sky it looked as desolate as any place I have ever seen. It did not group itself beneath its church and campanile after the picturesque fashion of the Ligurian coast-towns. Its houses seemed to have been dumped down anyhow. Its most prominent feature, after the church, was a large pink building which might have been a barracks or perhaps a school. Santa Teresa is, however, a comparatively modern settlement. It was built in 1808, by permission of Victor Emmanuel I, who named it after his wife (Maria Teresa of Austria).

We came to anchor in the narrow creek, and a magnificent official in a splendid black cloak was rowed out to us in a small boat. He was our first instalment of æterna auctoritas, and very impressive he was as he pored suspiciously over our passports. I heard subsequently of a fellow-countryman who recently attempted to enter Sardinia by way of Santa Teresa. Authority held him up for twenty-four hours while it telephoned to Sassari for instructions as to whether he should be allowed to proceed! Twenty-four minutes of Santa Teresa I should think would be enough for anyone, but twenty-four hours!

By the time the Englishman received permission to continue his journey he had had more than enough of Sardinia, and in disgust took the steamer straight back to Bonifacio.

LA MADDALENA

We backed out of the creek when the official had done with us, called at another miserable village, Palau, and at last, after nearly four hours’ buffeting, reached La Maddalena. For a long time the lights of the port had been an encouragement, and I thought joyfully of all that I had been told about the number of its inhabitants and the size of its hotels. At all events, it was a town.

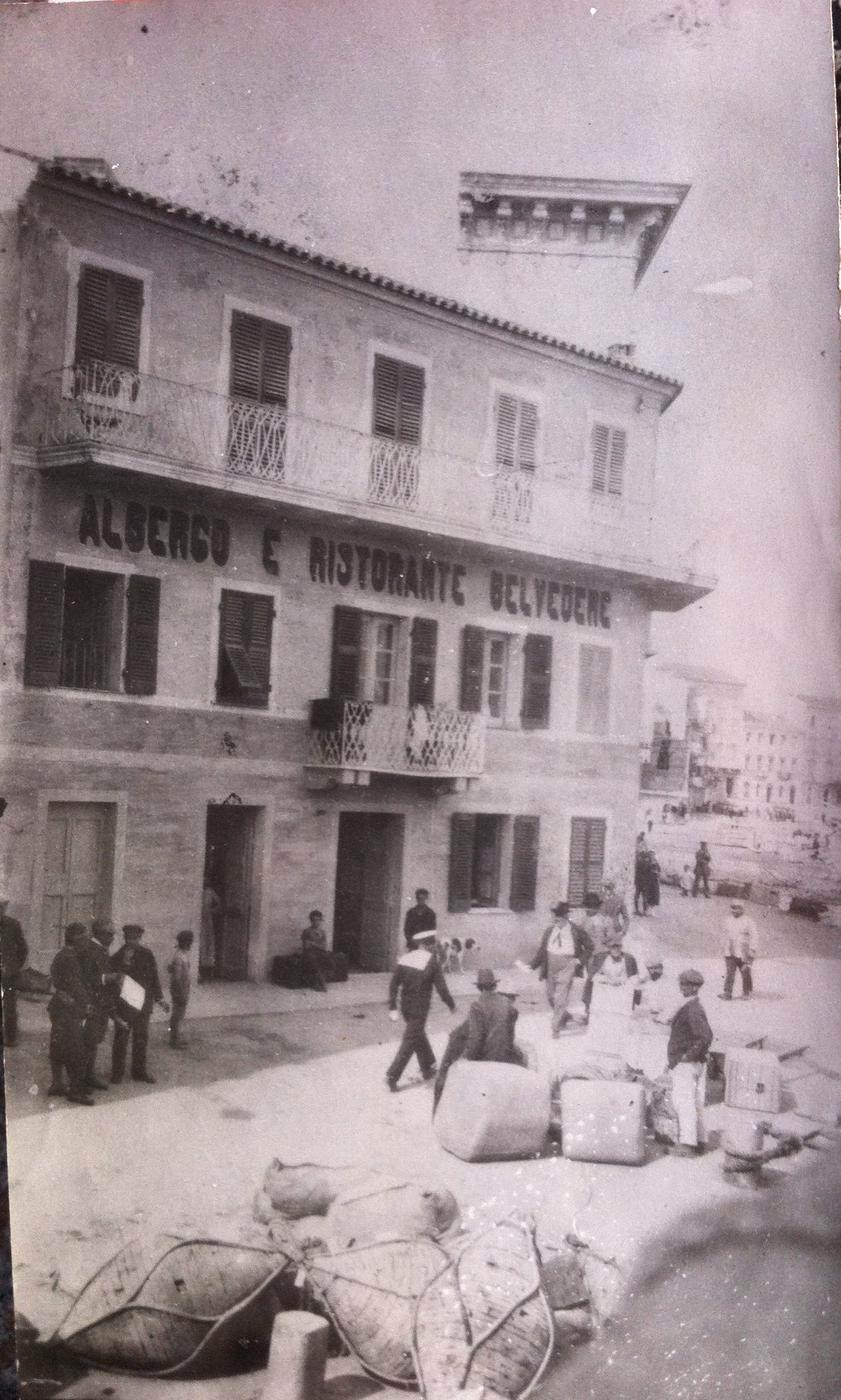

Some small boys seized our luggage, and in response to our inquiries about hotels gave us the names of two. “Which is the better of them?” we asked, thinking that one at least might be a kind of provincial Ritz-Carlton. “Ma!” They waved their arms expressively, and would not commit themselves. We could take our choice. We chose the Belvedere, which seemed to be the nearest, and set off.

But it was not to the hotel that our guides led us, but to the police. They dumped our suitcases in a draughty hall and waited while we were conducted upstairs into the presence of the authorities. The officials who examined us were not the resplendent carabinieri whom I came subsequently to know so well, but civilian functionaries. Instead of reading through our passports, stamping them, and handing them back, they made elaborate notes, and made them with ex- asperating slowness. Our mothers’ maiden names were laboriously written down, together with every other detail of our birth and parentage. After that there came a brief cross-examination.

“Who issued your passport ?”

“The late Lord Curzon,” I replied meekly. As he had the document in his hand I thought he might have discovered that for himself.

“What is its number?”

I hadn’t the remotest idea, but suggested, as politely as I could, that he might look and see.

The rain was beating against the windows of the big room, we could hear the wind howling dismally outside, and we were all three longing desperately for our dinners when, glancing at us each in turn, he put a final, pulverizing question: “Why have you come to Sardinia?”

The Swede and the Dutchman, struck dumb by this, cast appealing glances at me. “Travelling for pleasure,” I said, and must have looked as big a liar as I felt. However, instead of dispatching us to the nearest lunatic asylum, to be kept under observation, he dismissed us, but kept our passports.

The small boys again shouldered our bags, and off we trudged through the rain to the Belvedere. The Belvedere was certainly no Ritz. It turned out to be a long, shabby, three-storied, pink- washed house with a veranda, facing the harbour. There was a fair-sized restaurant on the ground floor, and after I had deposited my bags in a chilly, tomblike bedroom I went down to eat my first Sardinian dinner with the Dutchman and the Swede. The brandy, followed by our joint experiences with the passport officials, had broken down the barriers.

The restaurant was rather full when we arrived. A party of hilarious young men sat at a large table in the window. There were several officers in uniform scattered about, and just opposite me, sitting by himself, a pale, ascetic-looking Fascist in a black shirt. He was extra-ordinarily handsome; and had I been a film magnate I should have offered him an engagement on the spot. Most of the Hollywood lovers that I have seen either resemble Dublin gunmen of the lowest type or else look like ‘wop’ waiters. This young man had a pure classic beauty which would have made him look distinguished anywhere and in any clothes.

Despite the brutality of the weather and the discomfort of the hotel, I found myself warming to Sardinia. After the depression that broods over Corsica and the lazy self-indulgence of the Riviera, it was a relief to find oneself in an atmosphere charged with vitality.

One of the young men at the big table began to sing snatches of songs in a delightful tenor voice, and, finding that the room was enjoying it, continued, much to our delight. It was in the midst of this impromptu concert that P. M. suddenly arrived. He had driven over three hundred kilometres through the rain and then hired a motor-boat to cross over from the mainland a in order to keep his appointment with me—an example of reliability approaching the heroic.

Our host brought us another litre of heady local wine to celebrate his arrival. I had better, at this point, utter a word of warning to the uninitiated on the subject of Sardinian wines. They are often good, but always potent. Many of them (as I discovered that evening to my cost) have a kick like a mule. I am told that the malaria germ cannot prevail against them, and can well believe it. The evening, thanks to the rousing and vigorous red wine, ended on a top note of universal affability. Swede, American, Dutchman, and English-man saw not only each other, but also each other’s country, in the rosiest of lights, while as for Sardinia, with glass in hand and erect forefinger, it was allowed by all of us to be a one-hundred-per-cent. he-man’s island.

The next morning the rain had stopped, and a little watery, wintry sunlight gleamed on the puddles in front of the hotel and on the white sails of the fishing-boats in the harbour.

I had ordered my petit déjeuner and hot water to be brought to me at eight o’clock, little knowing that such attentions are unheard of in Sardinian country inns. You are not supposed to want hot water; and your caffè-latte and your bun, you must go down to the bar for them or else procure them at the nearest pastry cook’s. P. M. was still sleeping the sleep of the just when I set out to explore La Maddalena. It was certainly no metropolis with 15,000 inhabitants. I should be surprised to learn that it contained as many as 5000, its naval garrison included.

La Maddalena and the adjoining island of Caprera are two great lumps of granite, with tracts of cultivated land upon them.

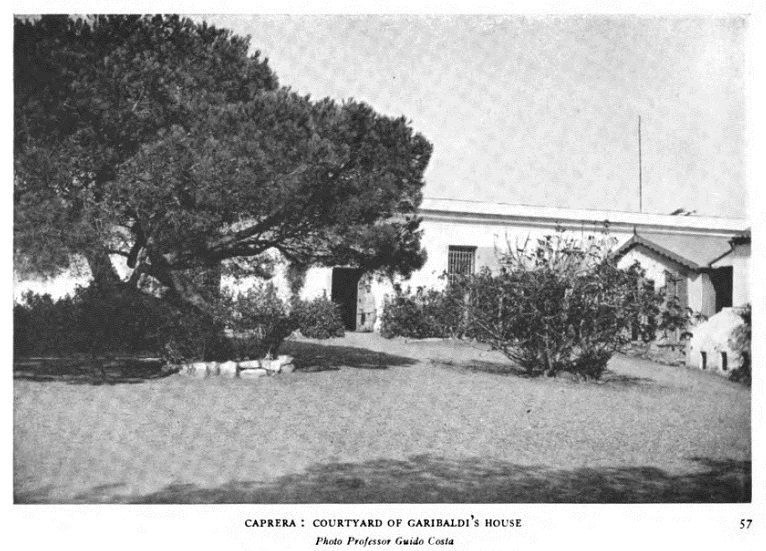

The town of La Maddalena is built on the south side of the island, and seemed a prosperous but rather forlorn little place. It is an important naval station, and full of officials suffering acutely from spy-mania. The only objects of interest for the tourist are the simple house and tomb of Garibaldi on Caprera, but to visit them one requires a special permit from the admiral in command of the port, which I gathered it was far from easy to obtain.

I did not make the attempt. In the first half of the nineteenth century there lived on Caprera an eccentric English family named Collins. The last of them, a Miss Collins, an ardent admirer of Garibaldi, bequeathed her house and lands to him, so that on her death he became the proprietor of the whole island.

La Maddalena has a certain interest for students of English naval history on account of its association with Nelson. He made the port his principal headquarters from 1803 to the beginning of 1805, while he was waiting for the French fleet to emerge from the harbour of Toulon. This they eventually did on January 17, 1805.

It was a dark winter’s night, and when the news came through preparations for dances and other festivities were being made on most of the British ships. Suddenly the order “Weigh” was given, and obeyed with lightning speed.

The passage was so narrow that only one ship could pass at a time, but within two hours the whole fleet was clear and stood to southward in pursuit of the French, whom they encountered at last at Trafalgar. His speed in getting off from La Maddalena is generally given as one of Nelson’s most brilliant and dashing exploits.

While he was waiting for the French to put to sea Nelson presented the church of La Maddalena with two silver candlesticks and a silver crucifix with the Christ in gold. When thanked for the gift and assured that prayers would be offered up for his victory over the French, he replied that “if they would only pray to the Madonna that the fleet would come out of Toulon, and it was all he asked of them, he would under-take to do the rest, and they should then have the value of a French frigate in silver to build a church with.

There is a local legend (whether founded on fact or not I do not know) to the effect that while at La Maddalena Nelson became enamoured of a beautiful girl named Emilia Isarra, and that it was she who inspired his gift.

Nelson had a great liking for Sardinia, and was well acquainted with all its harbours. He constantly impressed its importance on the British Government and urged them to acquire it. So poverty-stricken was the island in his day that he estimated that it could be purchased for £,500,000. Writing to Lord Hobart (March 17, 1804), he said: “It is the summum bonum of everything which is valuable for us in the Mediterranean. The more I know of it, the more I am convinced of its inestimable value, from position, naval port, and resources of all kinds.

” In a letter to St Vincent[1] he says: “I have written to Lord Hobart on the importance of Sardinia. It is worth a hundred Maltas in position, and has the finest man-of-war harbour in Europe. In short, it has nothing but advantages.” Just as La Maddalena proved advantageous to the British, so it was always a thorn in the side of Napoleon.

After the establishment of the Continental Blockade it became a vast and rich entrepôt for British merchandise. But Napoleon had an even stronger reason for disliking it. When he was a young man, in February 1793, he commanded the artillery in an unsuccessful attack on the town, led by Colonna Cesari. There is some evidence that Cesari, a Corsican, was secretly in league with his ostensible enemies. (The inhabitants of La Maddalena are of Corsican origin, and to this day speak a Corsican dialect.) Napoleon during the siege exclaimed that he would like to fire at the church as the people were going to Mass, “to frighten the women.” The shell was fired, but it rolled harmlessly to the steps of the altar and did not explode. The credulous townsfolk attributed this to the intervention of divine Providence. The more likely explanation, perhaps, is that the ammunition at Napoleon’s disposal had been doctored and the shells filled with sand.

After an attack which seems to have had about it some of the elements of a sham fight Cesari ordered a retreat, and the expedition returned to Corsica.

The famous shell was treasured afterward as a souvenir. A Mr Grieg, British Consul-General in Sardinia, purchased it for 32 écus. It changed hands several times, and now surmounts a marble pedestal on the quay at La Maddalena.

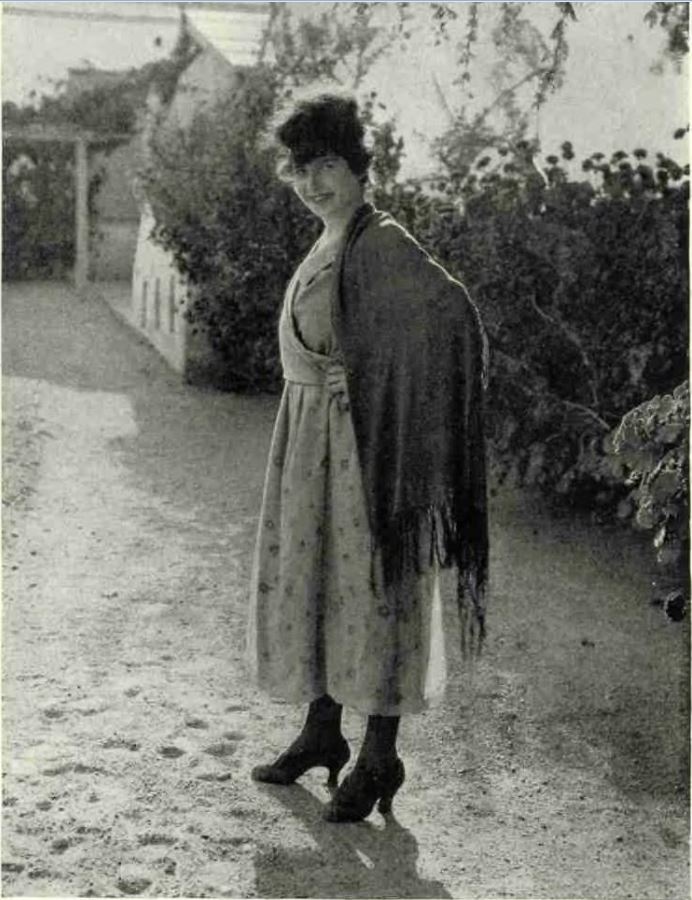

When P. M. made his appearance, looking none the worse for his experiences on the previous day, we strolled about the town in search of the beautiful women for which it has long been famous. But no examples of feminine loveliness met our eyes. Instead we were shadowed by passport officials. We gathered that the admiral himself was now investigating our family history. As we were anxious to cross to the mainland, we suggested with some vigour that our papers should be returned to us. The Swede and the Dutchman must have been more fortunate, as they had already departed by the steamer to Terranova.

When the passports were at last recovered we took our places in a roomy fishing-boat with a lateen sail, filled with a motley collection of peasants, animals, furniture, and merchandise. We went ‘first class,’ which meant that we each had a bedroom chair to sit on! After narrowly escaping shipwreck by collision with another craft, we soon caught the wind and went skimming across the harbour.

[1] The text of the letter accompanying the gift is as follows: “Victory, Oct. 18th, 1804 “REVD. SIR, “I have to request that I may be allowed to present to the church at Madalena a piece of Church Plate as a small token of my esteem for the Worthy Inhabitants, and of my remembrance of the hospitable treatment His Majesty’s feet under my command has ever received from them. May God Bless us all. “I remain, Revd. Sir, “Your most Obedient Servant, “NELSON AND BRONTE “The Revd. Dr Scott will present it to you. “The REVD. THE SUPERIOR OF THE CHURCH AT MADALENA.

Of all forlorn spots it has ever been my chance to visit, I think Palau takes the palm. It consists for the most part of a dreary street of one-storied, pink-washed cottages. excuse for its squalor it cannot even claim antiquity, for it has grown into existence only during the past decade.

Outside the miserable and dirty inn, where a handful of peasants were eating a loathsome midday meal of purple octopus, there stood a very smart red motor-omnibus, which carried passengers and the mail to and from Sassari. It seemed incongruous, but Sardinia, as I was soon to learn, is an island where the latest developments of modern science everywhere jostle the primitive and primeval.

We had to wait for the best part of an hour, while As an the proprietor of the petrol pump finished his luncheon, before we could get our tanks filled and leave this uninviting spot.

After crossing a swift stream, the Liscia (which probably abounds in trout), we came into rolling, pastoral country, a country of ‘great open spaces,’ bounded by granite hills.

Flocks of sheep and goats, in charge of shaggy-looking peasants dressed in sleeveless sheepskin jackets, passed us on the road, and others could be seen dotted here and there over the countryside as far as the eye could reach.

Once we passed a peasant woman dressed in a pale blue cloak and hood, who looked as if she had stepped straight from some fifteenth- century picture of the Madonna, and on the road near Tempio we encountered three little gnome-like men in black cloaks with pointed black cowls over their heads, mounted on wiry Sardinian ponies.

It is a strange, desolate, oddly exciting district, this Gallura, wild and sparsely populated, and not without a queer kind of charm.

TEMPIO

As we entered Tempio, a grim little city of about ten thousand people, built of grey granite, the rain began to fall in torrents, and we were glad to take refuge in the nearest inn to eat a belated luncheon.

Tempio is the capital of the province of Gallura, and the seat of a bishop. It stands some 1800 feet above the sea, on a northern spur of the granitic mountains of Limbara, and contains little of guide-book interest. We were too jaded to visit the cathedral, or even the colossal nuraghe on the road to Nuchis, to the north-east of the town, which from its size is called Nuracu Majori. I was to see many nuraghi during my stay in Sardinia, and shall have something to say of them later in this narrative.

For lunch we regaled ourselves upon roast kid and strong red wine, and we had scarcely finished our meal before Authority, in the shape of a seedy-looking official in mufti, came to investigate our family history. I was not yet properly broken in to the tireless suspicion of the Sardinian police, and became a trifle restive while the investigation proceeded. Luckily my Italian is almost non-existent, and P. M. had the good sense to be mellifluously polite, so that the investigator let us depart amicably.

Tempio makes a liqueur, which we investigated without enthusiasm. For the rest, apart from its cork factories, it seems to concern itself chiefly with the sheep and goats pastured in the surrounding countryside. The sheep-shearing is the principal event of the year, and in connexion with it are the annual fêtes called graminatorgiu, or ‘wool-pickings.’ From the wool coarse serges called furresi are made, for local use, by the womenfolk.

There seemed little about Tempio to justify its idyllic name, but the scenery in its neighbourhood, even in winter, had a certain rugged beauty. To the north, by Aggius, stretched a long line of saw-tooth peaks, and to the south were the high summits of the Limbara range.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

coll. LA MADDALENA ANTICA “La storia da condividere” (Facebook), coll. Navi e armatori, Erennio Pedroni, Domenico Melia

Contemporary Photos

Antonio Concas – Flickr; Roberto Gamboni – Flickr