ARZACHENA

by Mary Davey

Sardegna Icnusa, or, Pleasant reminiscences of a two years’ residence in the island of Sardinia

Binns and Goodwin; E. Marlborough, Bath, London

1860

Tempio, though interesting enough in its way, does not afford amusement for a long sojourn; it is determined to go, with the military escort, to the celebrated festa of Arsaquena: it is a sort of religious festival, which annually takes place in this bandit region. There are very many of these annual festas in various parts of the island varying in some particulars, but that of Arsequena, being on a large scale, may serve as a description of all.

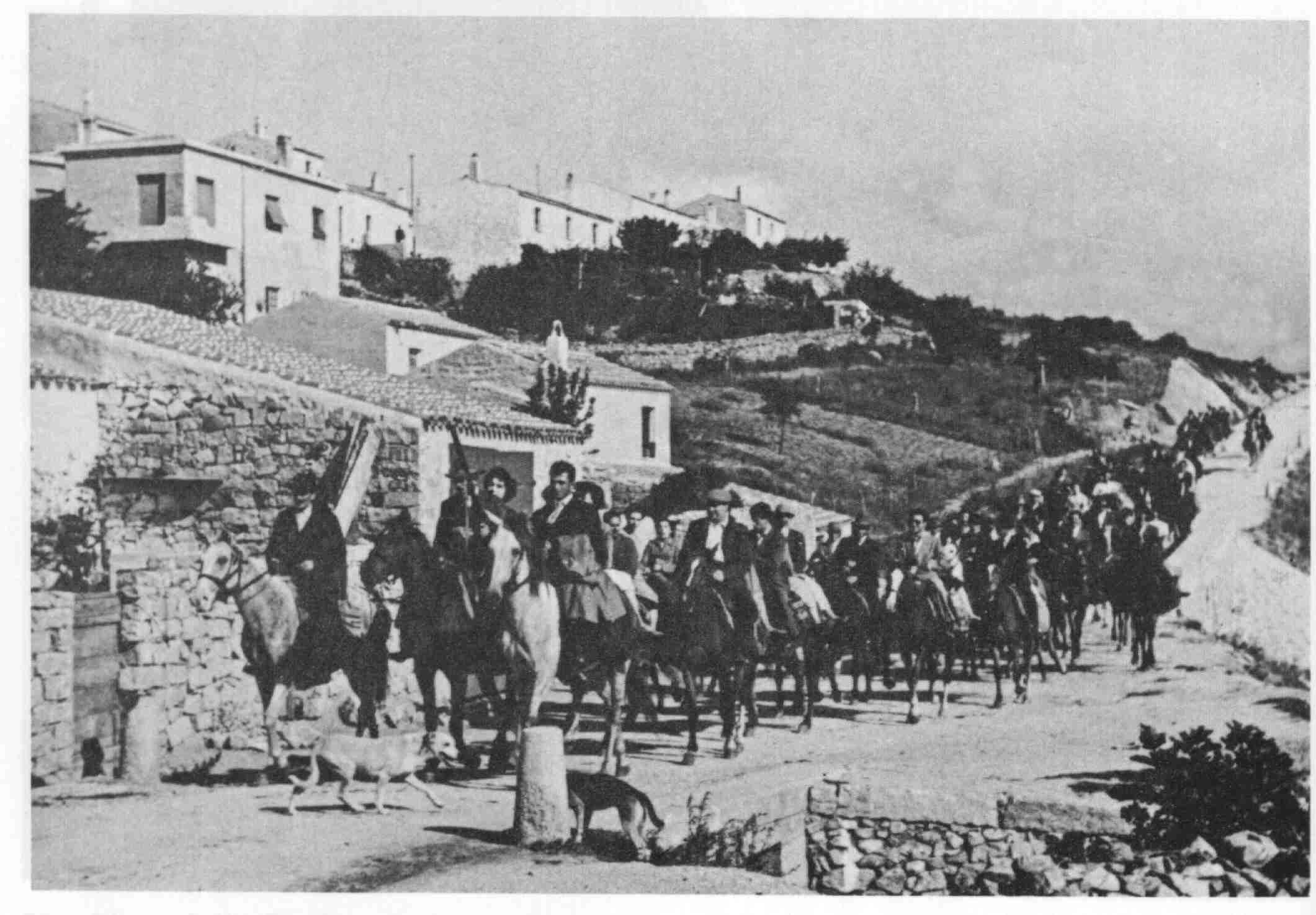

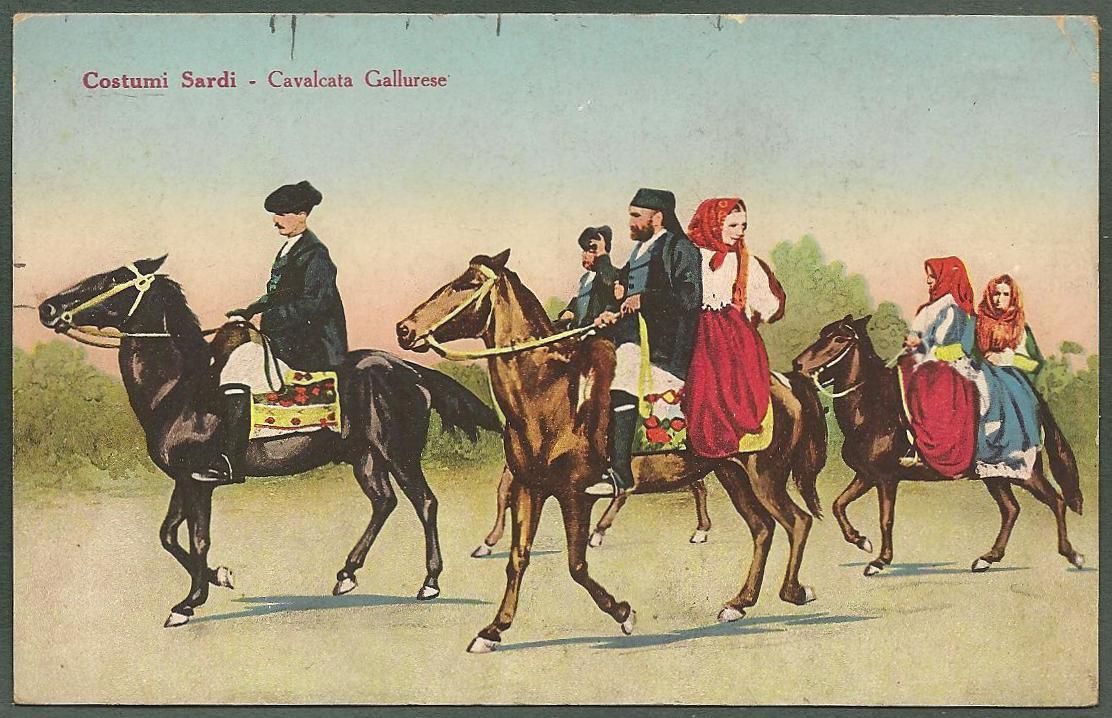

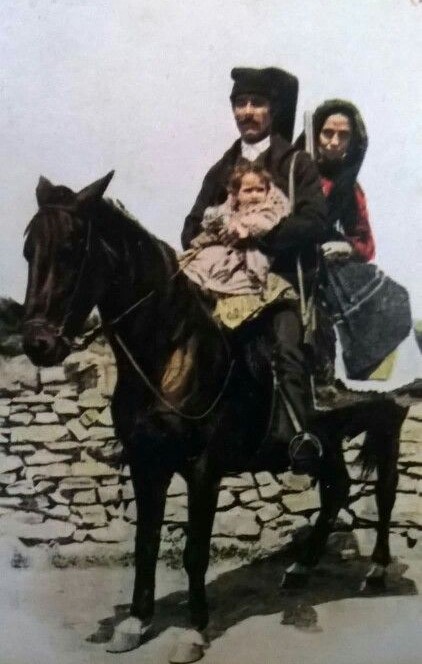

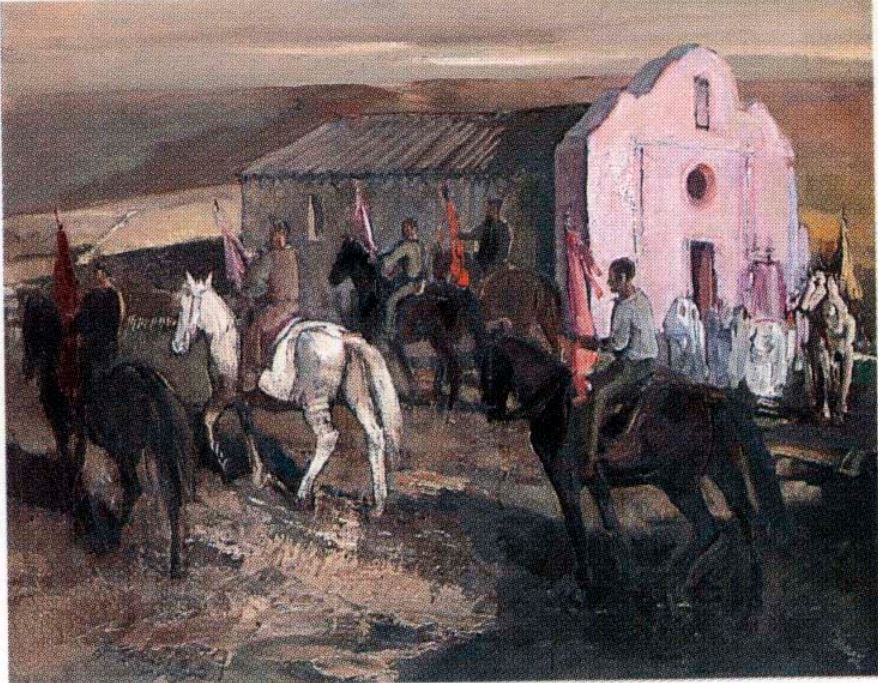

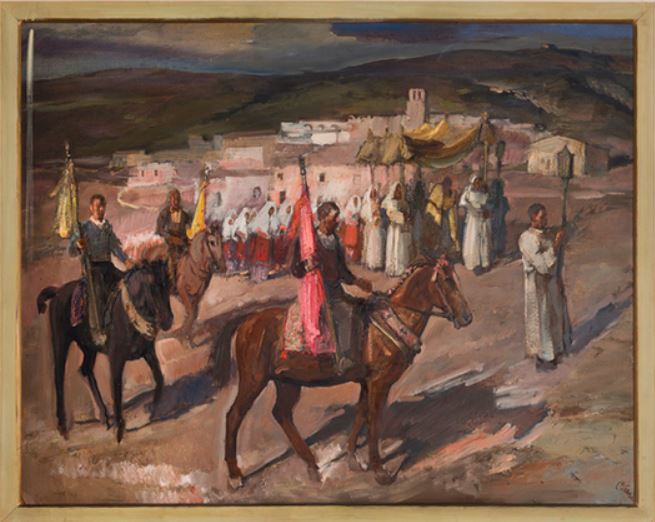

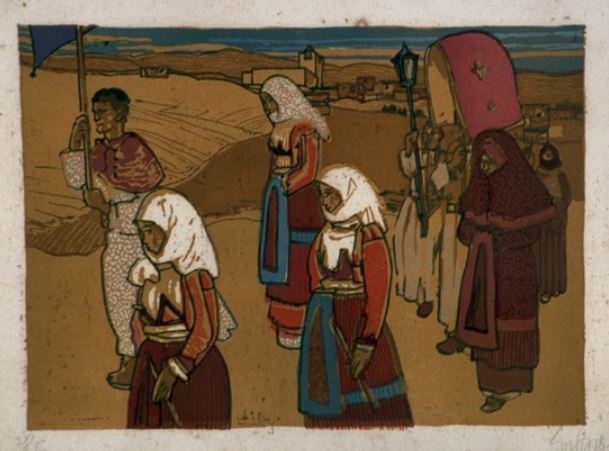

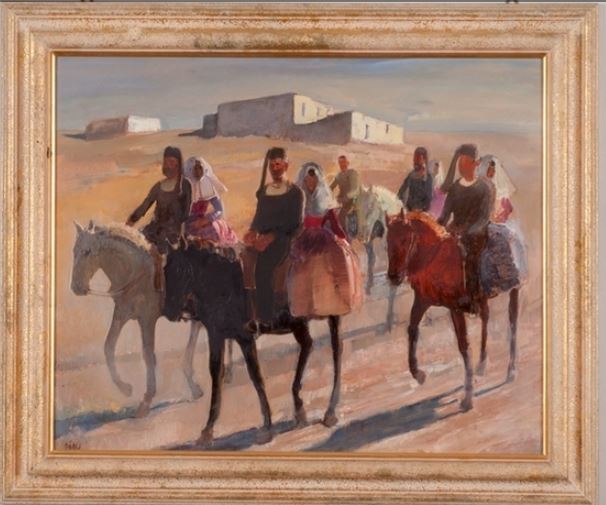

The mountain paths are all alive with pilgrims for such they are, although after a very joyous fashion – in every variety of costume; whole families are trooping along, all in full gala attire, on horses, in bullock carts, on foot; but of the latter there are very few for Sards are no pedestrians.

Who can describe the scene of the festa? On a beautiful hill, partially covered with lovely trees and shrubs, is perched the little chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary of Arsequena

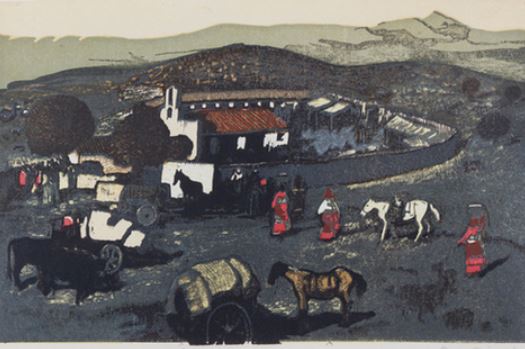

A wooded plain lies stretched beneath, and this is teeming with life, and in a ferment of bustle and activity. Hundreds of horses are tethered in groups to the trees around . Here and there, in the distance, may be seen impromptu abatoirs, where the processes of flaying and slaughtering are in progress; then fires of charcoal, in the oddest of ovens, made in the ground; such boiling, and frying, and stewing, al fresco; a gipsy encampment en grand.[…]

A long tract of ground was covered with rushes, myrtle, and lentiscus boughs, or the scilla marittima, to the height of five or six inches. This was to serve as a table for the vast multitude.

The directors of this rustic festival, are called, for the time, “soprastanti” they are forty in number and are the capo pastori, or chief shepherds of the district; they have each severally contributed a sheep or goat, twelve pounds of cheese, thirty pounds of bread, and, collectively, I cannot say how many hundred gallons of wine; several casks of oil, huge quantities of maccaroni, fruits, vegetables, confetti, fuel, and cooking utensils. These important personages are high in council – directing, arranging, debating.

The upper portion only, of this singular table, is covered with snowy napkins, and is intended as a place of honour for superior guests.

Our English party are hailed with ‘clamourous delight’, and are enthroned in state under a canopy of cabanneddus (great coats) stretched from bough to bough, and left to enjoy the novelty of the scene at their ease, until the banquet shall be served.

Edward, of course, is an important auxiliary, and is continually consulted! “Do the milordi like this? Do they prefer that?” Bertoldo, too, is on stilts; he is in the very zenith of importance and popularity.

The grand dish, par excellence, is now placed with all éclat and ceremony at the very top of the monstrous table. It consists of a huge wild boar within the carcass of which has been placed a kid, inside the kid a sucking pig within the sucking pig a quail or two; and the whole mass roasted entire in a hole in the ground, lined well with myrtle branches, and covered over and under with embers of charcoal.

Besides this grand national dish, in are divers parts of the table are sheep, deer, goats, sucking pigs, wild hogs, &c., roasted whole in the same manner; tubs of maccaroni cooked with cheese, and miniature mountains of water melons, figs, and grapes; branches of myrtle serve for plates and dishes, daggers for knives, twigs of myrtle are cut into what serve for forks. The feasting begins in earnest now.

Sards are no contemptible gourmands. The hilarity scarce knows bounds – the clatter is universal.

The English guests and their young Piedmontese friend are treated to the daintiest morsels and served with the most courteous hospitality. The soprastanti insists on having the honour of waiting on them in person, and vie with one another in their attentions.

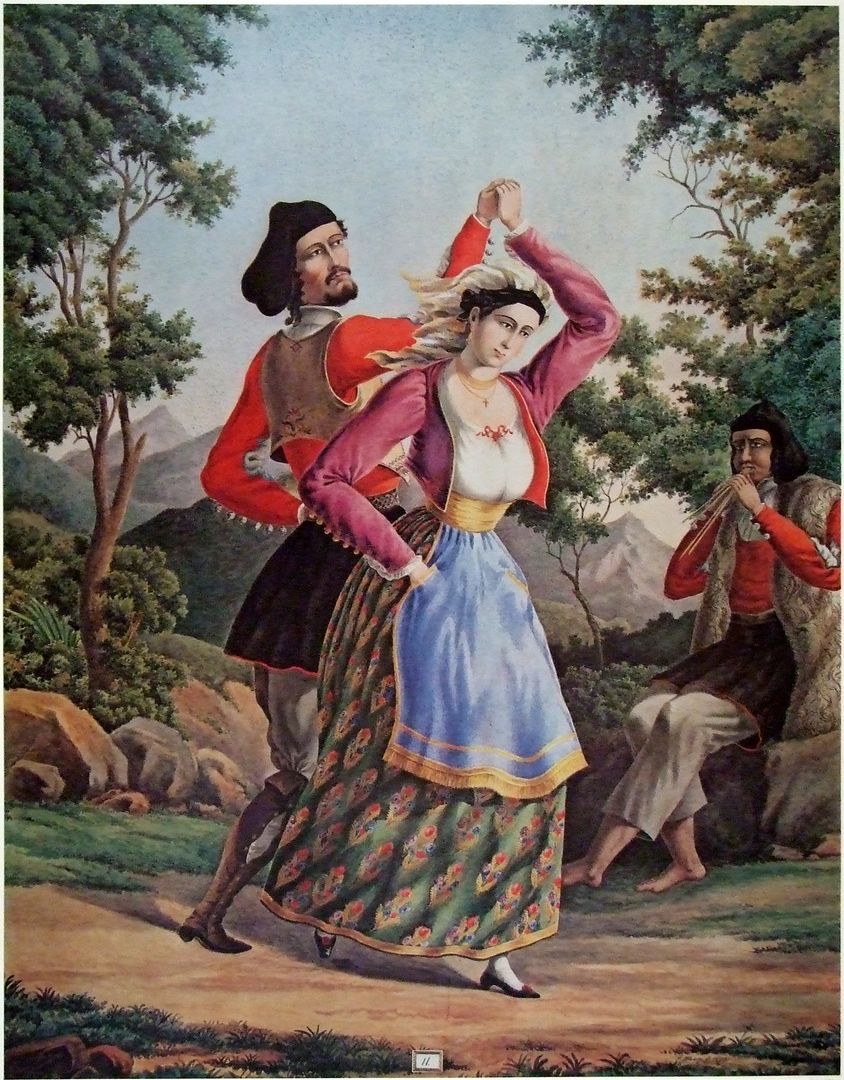

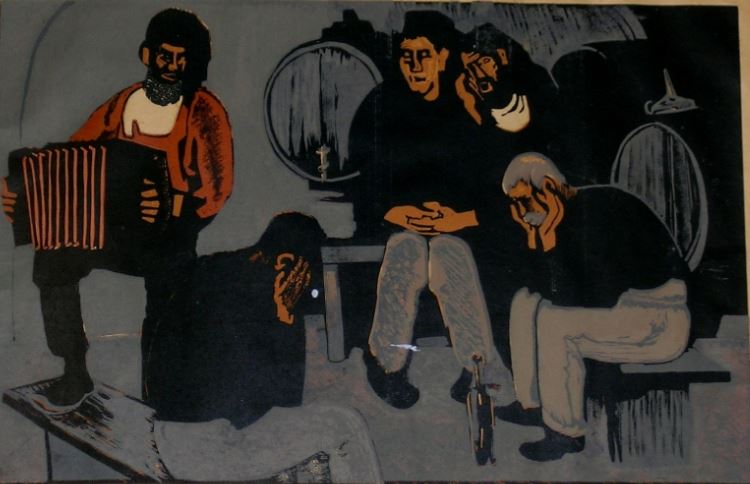

The feast over, amusements begin; the ballo tondo, as a matter of course, has begun its sinuous maze, then other national and more they dances – salto sardo and pelicordina are also in full activity.

Poets are reciting in a coarse recitative; orators haranguing; tale-tellers declaiming; and glee-men singing.

It is sunset-the “Ave Maria” peals; every head is bent, every lip moves to the prayer.

Night falls – the bright stars peep out from the purple sky – so clear, so bright, the only canopy over that vast multitude. Groups here, groups there – nay, whole families, with their little ones, are curled up under the trees, fast asleep. Some lively spirits are inexhaustible: and so the song and the dance are not entirely at rest during the livelong night .

It’s morning, the sun very bright, and very hot, and the vast multitude assembled in the vale of Arsequena, are again on the alert. The chapel bell rings lightly and musically, but not as chapel bells ring in old England.

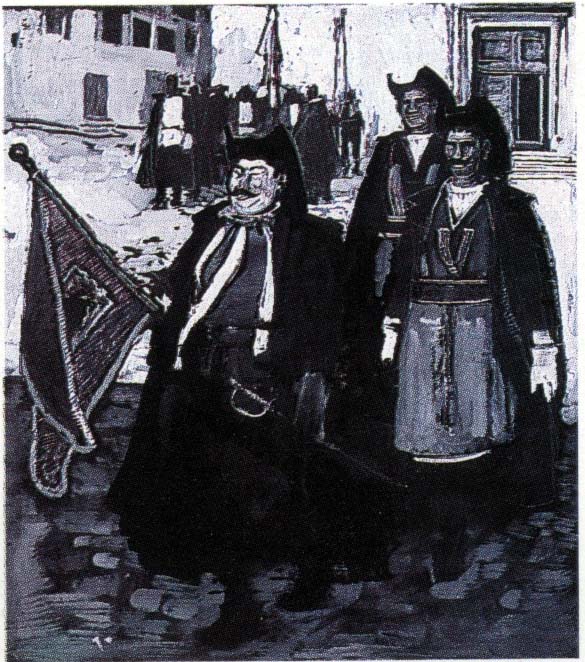

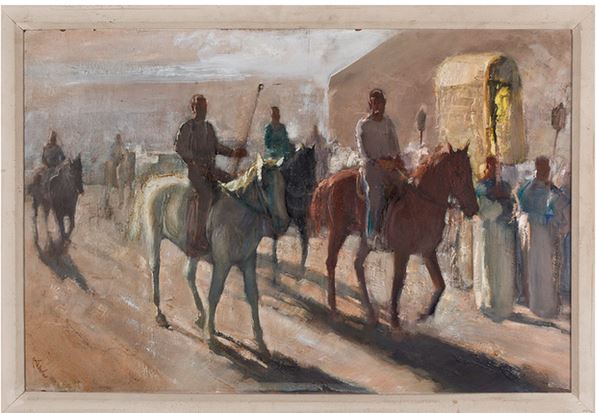

And now the grand procession appears, bringing the sacred banner of Tempio, surmounted by a cross. It is first planted in the open space at the foot of the chapel hill. Its richly – embroidered folds wave heavily in the soft morning breeze.

But look, now, at yonder handsome youth, mounted on the magnificent roan; he belongs to a family whose privilege for long ages it has been to carry the sacred banner up the hill: there he goes, leading the procession of priests, and gracefully waving it as it proceeds, as if to shed blessings on the multitude.

See the poor people prostrating themselves, catching hold of it, and devoutly kissing it in its progress . Well , theirs is a wild faith – a blind devotion , but very slightly removed from idolatry – but still it is faith; and faith is beautiful. The procession, with all its accompani- ments of groans, prostrations, sighings, and kissings, passes three times round the chapel, in the direction of the sun.

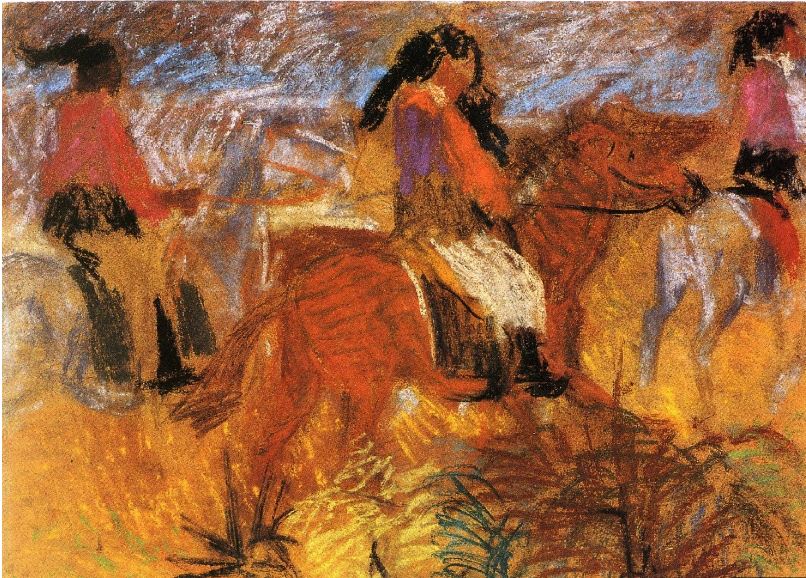

Now comes a horse – race, after the wild primitive fashion of the country. The half – clad figures carelessly reclining on the unsaddled backs of horses scarcely less wild than themselves, their long elflocks dangling over their reeking flanks. There they go, tearing along, over streams and brushwood shrubs and stones. How strangely different to the trim jockey of an English race – course! [Note: this paragraph has been moved from its original position because it was obviously taken out of context].

Meantime, the table is again spread for the mid-day dinner (no account is taken of breakfast-a bunch of grapes, or a few figs serve), and again all is hilarity and feasting. It is a prettier sight than ever, for troops of bright-eyed children who were asleen the evening and patiently await the scraps.

The champion of the banner-who is altogether a person of superior class, a young noble of Tempio – fraternizes with Champion Charley, and they mutually make eccentric endeavours to render themselves intelligible. […]

To dinner, of course, the siesta succeeds; and then the dancing and singing, poetising and declaiming recommence, only to be interrupted by the substantial supper, as on the previous day. […]

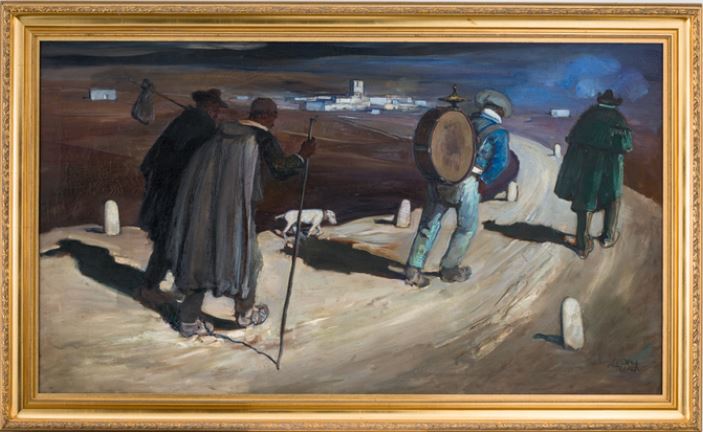

On the morning of the third day, the multitudes disperse, some to another chapel at some distance off, dedicated to St. Pietro di Baldovinu, where the ceremonies and the feasting are continued for the day, others to their homes.

There is a great deal of regret at parting the young Piedmontese is especially sorry to part with Charley and Edward; and, after an interchange of cigar cases and good wishes, they severally take their separate ways.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs (captions translated freely)

by Giuseppe Biasi, from Catalogo Beni Culturali

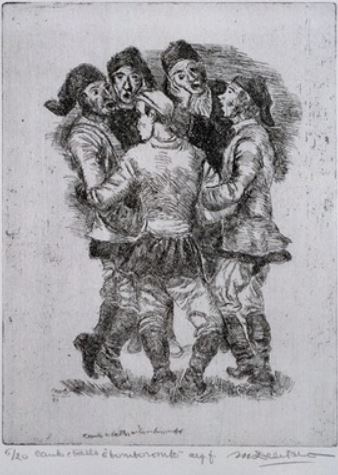

by Mario Delitala, from Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Antonio Ballero, from Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Giovanni Marghinotti, from Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Stanis Dessy, from Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Pietro Antonio Manca, from Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Simone Manca di Mores, in Simone Manca di Mores, Raccolta di costumi sardi, Cagliari, Della Torre, 1991

Postcards and photos from the 1800s and early 1900s

coll. Francesco Cossu

Contemporary drawings and photos

by Gallura Tour, Hans Leysieffer