MARIA SCANU

A TALENTED SARDINIAN ARTIST AND SCULPTOR

AMID THE GRANITE AND THE SEA OF PUNTA FALCONE

(SANTA TERESA GALLURA)

MARIA SCANU, registered at birth with the surname Cruciani, was born in Oristano on September 27, 1931, to a mother from an ancient and noble Sardinian family and a Roman officer stationed in Sardinia for service.

From a young age, she attended the Oristano Institute of Art, demonstrating a particular aptitude for figurative arts. After marrying Oristano entrepreneur Piero Salvatore Scanu, she became known by the surname Scanu.

A decisive moment in her career came in 1988, when at the age of 57, she undertook studies in art and modeling in Florence, attending the University of Free Age. Despite starting relatively late, Maria quickly made up for lost time thanks to her innate talent. Soon, her first sculptures emerged, revealing the artist within her, shaped by her remarkable craftsmanship and deep spirituality. Her work quickly attracted the attention of critics, art dealers, and collectors.

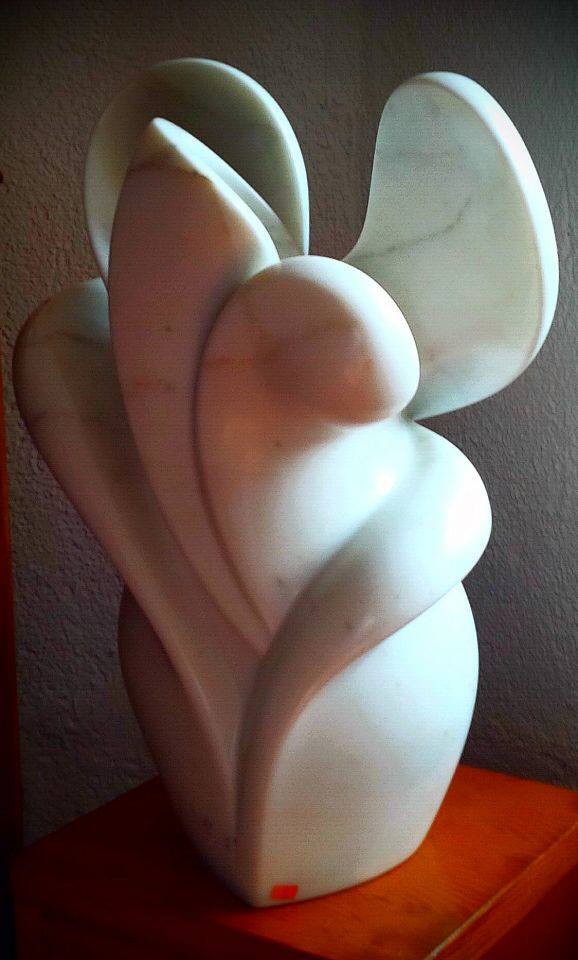

Classical staticity did not appeal to her. She was drawn to contemporary art. Influenced by Alberto Giacometti, Hans Arp, Henry Moore, and Fernando Botero—pioneers of modern art—her prolific work, including an extensive series of bronze, marble, and granite sculptures, was dominated by fluid lines and sinuous, feminine curves.

She never favored one sculpture over another, stating:

“My satisfaction comes while I work, while I express myself. The sculpture fulfills me as I create it. Once it is finished, I have already detached from it.”

Certainly, she appreciated the opinions of art experts and critics, who admired the dynamic perfection of her lines, the interplay of light, and the uninterrupted volumes. However, she was even more gratified when “ordinary people” spontaneously reacted to her sculptures by saying, “They are soft,” and felt “the need to touch them.”

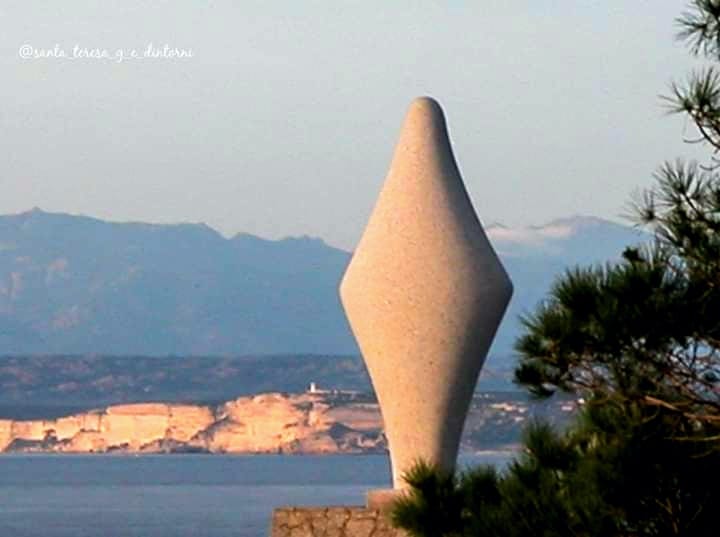

One might wonder what Maria Scanu would have thought about the opinions of “ordinary people” in the era of social media. The reference here is to the moment of great online popularity surrounding her sculpture Madonna of the Sailors in Santa Teresa Gallura, inaugurated in 1999. For 22 years, the statue stood there—beautiful, maternal, and discreet—under the town’s famous tower, facing the sea and sailors. Then, in 2021, a Facebook post on the Sardegna Che Passione page praised the statue, stating:

“Santa Teresa Gallura. The artist who created this beautiful granite work is the talented Maria Scanu. The title of the work is Madonna of the Sailors.”

This post unexpectedly turned the statue into a viral “case”, attracting attention from both Italian and international newspapers. Many online commenters claimed that the Madonna essentially resembled a female vulva.

Although Maria Scanu would not have appreciated the banality or even vulgarity of some remarks, she would likely have respected them and not taken offense. After all, even so-called “educated” individuals, including self-proclaimed artists, can make superficial judgments. At the same time, many “ordinary people”, as she called them, expressed sincere appreciation with sensitivity, intellectual depth, and even artistic insight. Ultimately, Maria Scanu would have thanked her Madonnina for drawing worldwide attention to her as a woman and artist, granting her the widest and most unexpected recognition.

Among her other significant public sculptures, the powerful War Memorial in granite in Santa Teresa Gallura and the large bronze fountain in Corte di Santa Maria in Sassari deserve special mention.

Her sculpting process always began with a drawing—a quick sketch, two or three lines at most—followed by a plaster model to study light and form. The Golfer took her three years to complete.

She deeply believed in hard work, advising young artists:

“Work and work. Experience, technique, and skill develop and refine only through work, not talk. And in working, you realize how much more there is to improve.”

For her, freedom and independence were essential qualities in an artist:

“A sculptor must feel free to express themselves as they wish.”

A gallery owner, after seeing some of her Madonnas, requested only Madonnas from her. After making a few, she grew tired and ended the collaboration.

Other essential qualities for a sculptor, in her view, were modesty, simplicity, and authenticity. Her personal experience had taught her that “the great ones were humble.”

She found satisfaction and pride (she called it “amusing”) when twenty of her marble works were chosen to accompany the presentation of a prestigious car:

“They came to my house, photographed them, packed them up, transported them, took them on a six-month tour across twenty German cities, and then returned each piece to its place without a scratch. That’s what I call ‘truly German’!”

From the 1980s until her death, Maria Scanu lived and worked between her home in Florence and—above all—her residence in Punta Falcone, Santa Teresa Gallura, near Resort Punta Falcone, founded by her husband Piero Scanu (who also built the nearby Marmorata hotel complex and founded the Ruoni district). The resort is now managed by their daughter, Cinzia Scanu, surrounded by granite rocks, mastic trees, and the sea, with a view of Corsica.

Coming from a wealthy family, she never needed to sell her works, many of which are now preserved at the aforementioned resort. Free from economic constraints, her relentless work and creative fervor stemmed solely from a spiritual necessity.

She passed away on May 27, 2016.

CARESSES OF IMAGINATION

That tactile sensation—so pleasant, capable of revealing subtleties otherwise imperceptible yet undeniably present in the completeness of the form offered to visual exploration—is the result, yes, of a high level of technical mastery, but above all of a particular sensitivity that Maria Scanu pours into her sculptures.

The material surrenders to the caresses of imagination, gradually yielding only what is superfluous, which might otherwise deceive the form—much like oily skin under the persuasive massage of a brilliant aesthetician.

You can sense all of this by lightly running your hand over the polished marble that arches into a human back—though, in truth, a transfigured one, as if caught in an unfinished metamorphosis, playing hide-and-seek with the magic to which the stone is subjected. A kind of pagan, sacrificial ritual, invoked to offer up, time and again, the hard-won results of artistic struggle, fueling a relentless and unwavering process of renewal that has continued for years.

Thus, the accumulation of knowledge—experience layered upon experience—ultimately led to a dramatic event that suddenly disrupted the determined yet cautious path of the Sardinian (now Florentine) artist. It seems as though a sudden illumination unexpectedly shattered that barrier of “figurative propriety” which had prevented the artist from venturing beyond the limits of common sense and grasping new sensations in the free expression of emotions—those fantastic emotions so often brushed upon in the forbidden dreams that abound in the higher realm of Art.

And so Maria Scanu, through a phenomenon that appeared sudden but was not, conquered that territory; she seized those dreams. One cannot help but wonder whether the artist’s work was psychologically influenced by that sort of paradise stolen from the angels who once dwelled upon the hill of Settignano: a home, a marble workshop, an observatory hidden in greenery, gazing upon Florence sprawled lazily in the valley below, where the Arno meanders with equal indolence. A laboratory of ideas capable of playing with the sacred forms of Brunelleschi or Arnolfo, in a chase of shadows and light, where matter dissolves only to reassemble in an endless sequence of abstractions—perhaps irreverent, yet profoundly evocative.

And all the visible things from that enigmatic vantage point take on marvelous forms, bathed in light that cuts through them in singular angles, triggering kaleidoscopic plays of shadow and illumination, or suffusing them until they appear diaphanous, as if carved from alabaster.

It is the rhythm of those visions, in my opinion, that served as the driving force behind the surge of imagination that revolutionized Scanu’s artistic path.

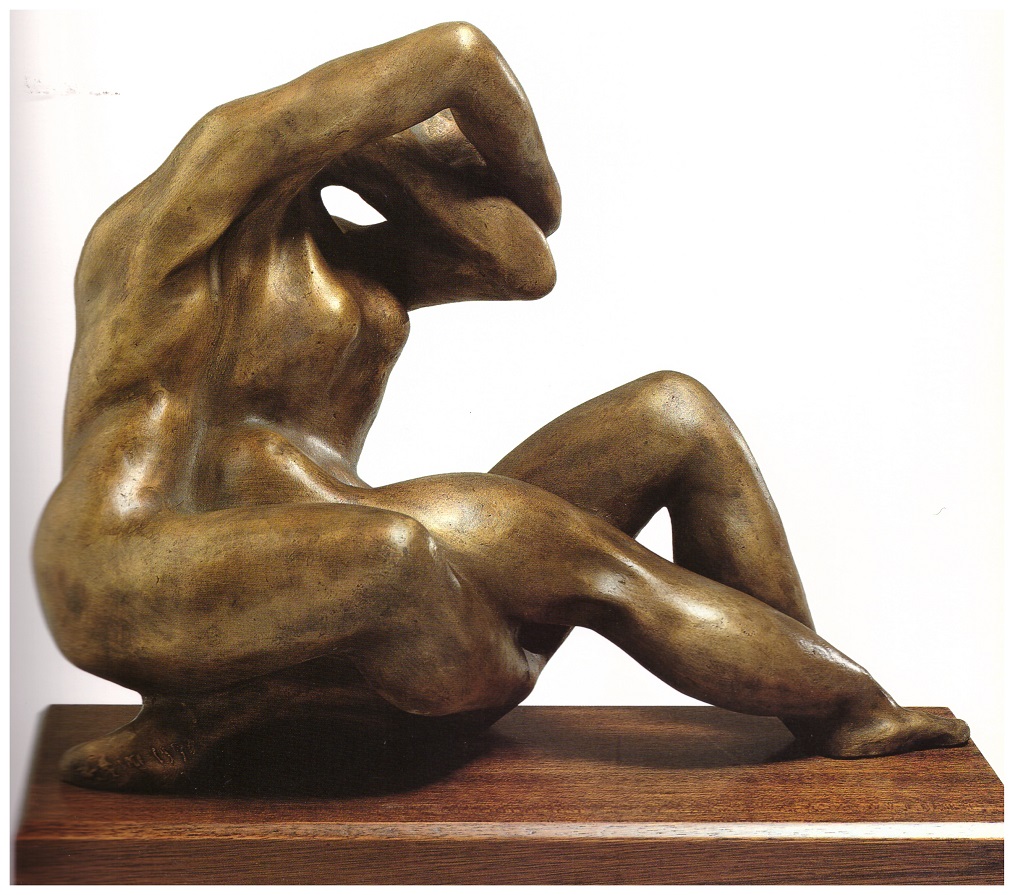

Revisiting the bronzes that marked the earlier part of her career—a phase of dutiful adherence to the figurative—it seems clear that even then, the sculptor was already sensing certain presences, perhaps perceived at the time as supernatural. This may explain why the “sacred” demanded a form of reverence, which she shaped with an expertly trained hand, though still burdened by traditional academic frameworks.

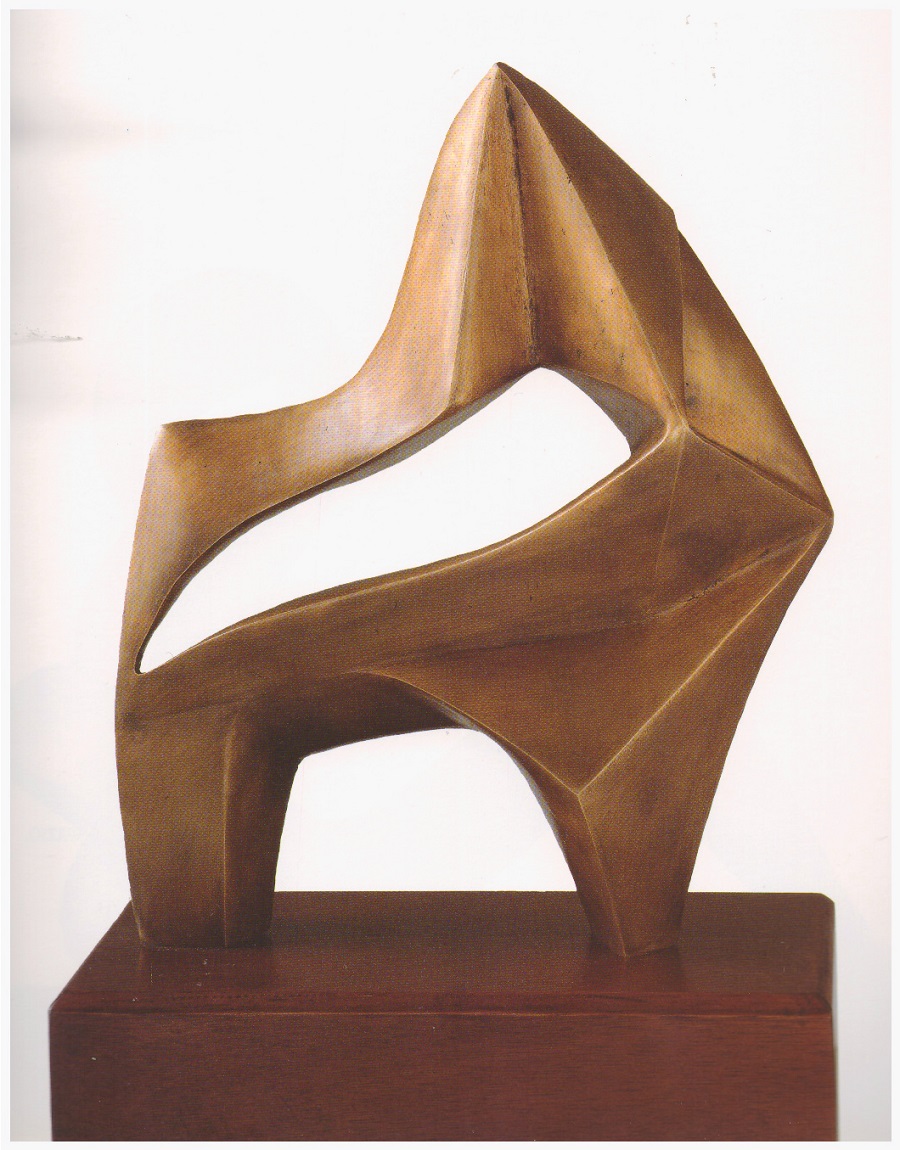

Then came the leap. A leap in language as well, for it was the newly charged emotions that dictated its scale and scope. From that moment, her maternities were filtered through an almost enchanted lens, dissolving into reconfigured shapes—at first geometric, then increasingly focused on the interplay of solid and void. The old lessons on balance remained, yet the concept of form had evolved into a new mental approach to positive and negative volumes.

It is not my habit to make explicit references to artistic forebears, as invoking the names of artistic giants often serves more to showcase the cultural erudition of the critic than to aid in truly understanding an artist’s creative process. Yet, how can one entirely dismiss certain comparisons made by others? How can one fail to think of Moore, for instance? Or to recall the exquisite, impeccably polished surfaces of Arp, seamlessly integrated into the dialogue between mass and emptiness?

These are, ultimately, cultural reference points against which the validity of Scanu’s new artistic choices can be measured—venerable, time-tested guardians of extraordinary achievements, won through both sacrifice and joyful experimentation. They are authoritative mentors, guiding the autonomous inventions that Maria Scanu continues to offer for all to observe—not to astonish, but to quench, time and again, the insatiable thirst that drives her artistic quest.

A SCULPTOR IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Maria Scanu, in the span of just a few seasons, has fully embraced abstract figuration.

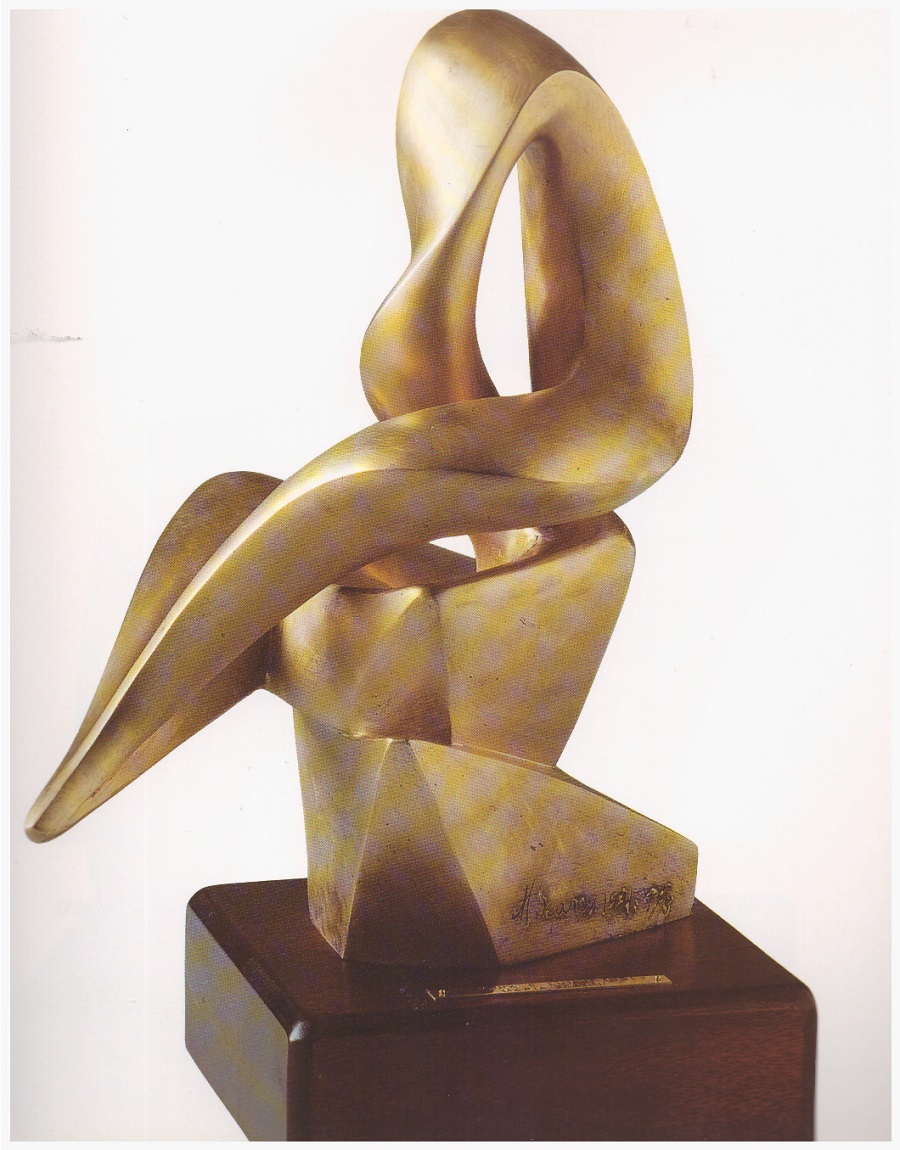

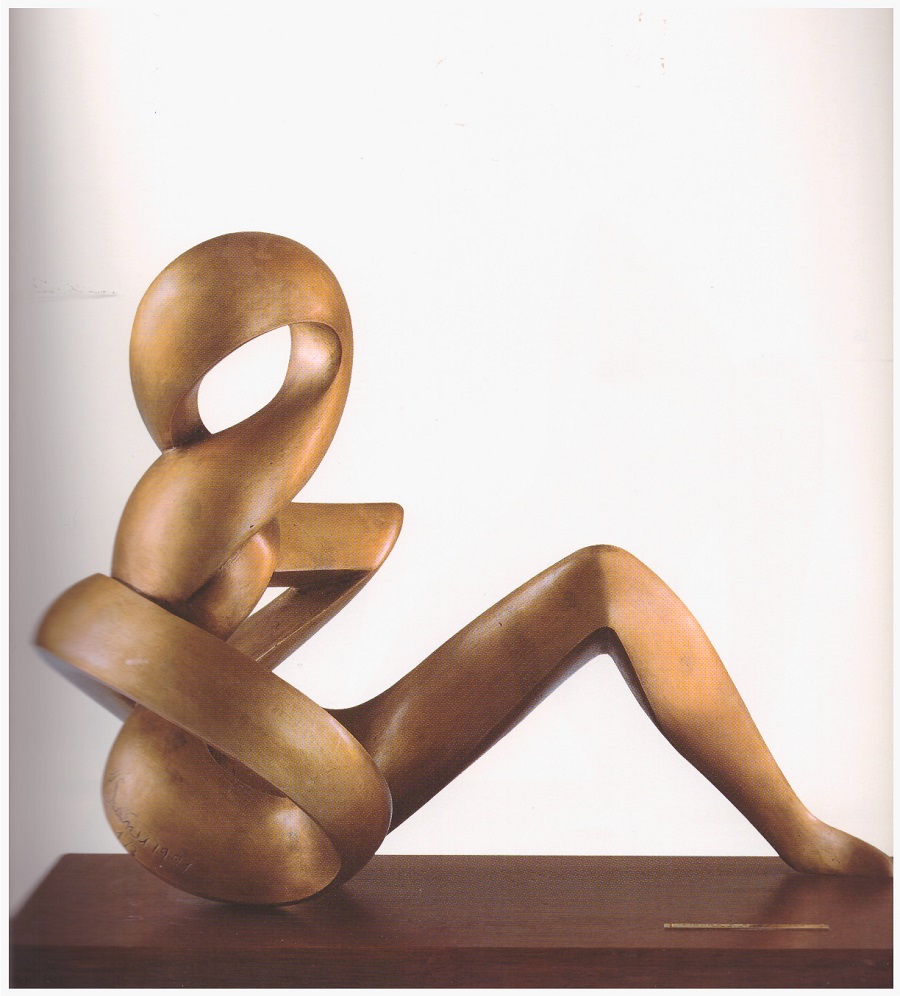

The distinctive feature of Maria Scanu’s bronze sculptures lies in the fact that, as her abstract style becomes more pronounced, the human reference does not fade. Instead, it is preserved through the crouching and inward-bending of the figure, through the way life wraps around itself in a dynamic embrace, without losing its identity—rather, it rediscovers it within the abstract form. A prime example of this is Intreccio, a bronze work from 1992.

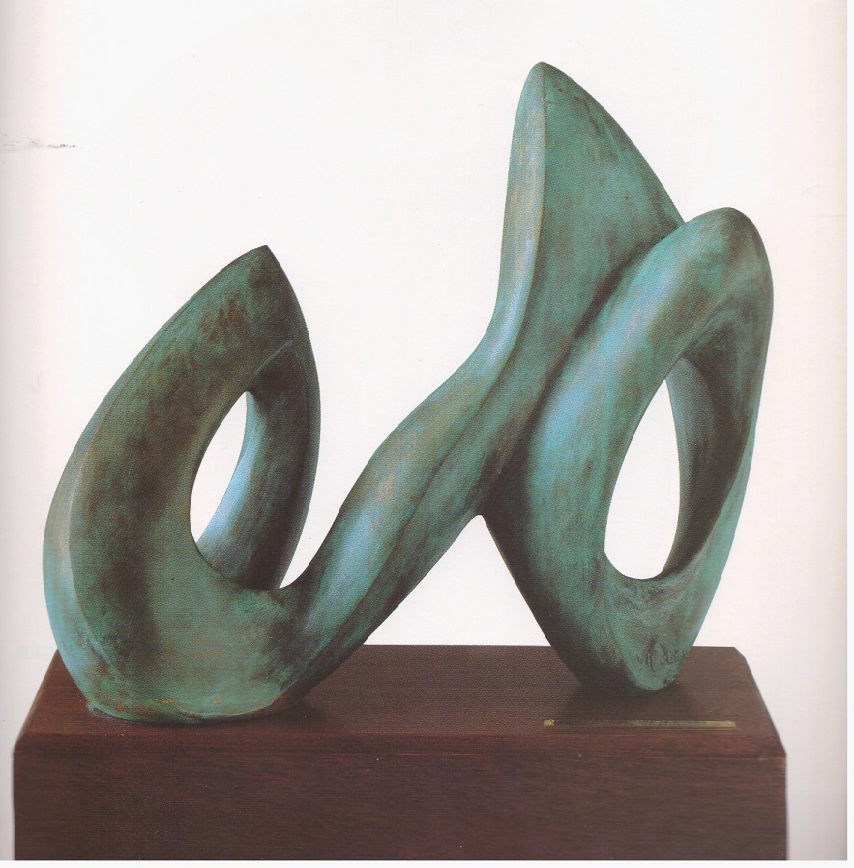

Another brilliantly titled bronze piece by the talented Sardinian sculptor is Figura e Linea. Here, abstraction and naturalism confront each other, clashing in search of harmony within a more tormented interplay of shapes, alongside moments of deep pathos inherent in the human form. When viewed from certain perspectives, under specific lighting and angles, the figure appears to embody an entire struggle, to borrow a term dear to Luigi Carluccio.

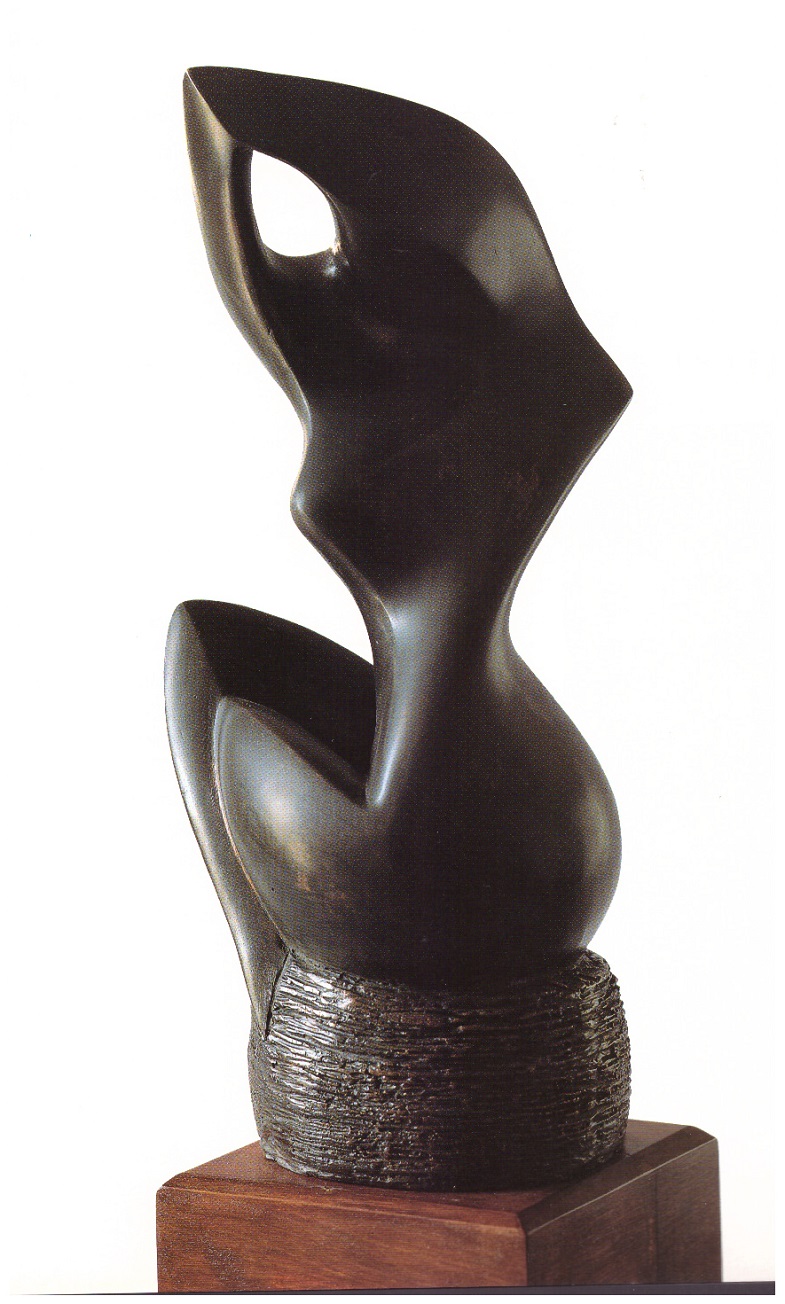

And what can be said of Seduzione, a rich and dynamic trophy of life? The chosen material—Belgian black marble—is used by the artist with remarkable mastery, blending seamlessly with the sharp contours and the rhythm of an existential obsession, as if Boccioni’s dynamism were tempered by the carnal versatility of Arp.

I am convinced that the patinated plaster work La Danza would have found its most fitting and meaningful realization had it been cast in bronze. The entwining of the legs, suspended in midair within the delicate rhythm of movement, as if lifted lightly by the wave of music—the fleeting moment already crystallized in Cubist synthesis—would have gained its eternal essence in bronze. However, the fact that this dancer, so ethereal and intellectual, entirely enveloped in the most fluid of sculptural lines, makes us envision a metallic version (a material both stronger and yet seemingly more flexible) speaks to an artistic soul of great solidity and depth.

THE POETRY OF MATTER

by Mario Morales

[Professor, Superintendent of Studies in Belluno, art critic. An artistic circle in Belluno has been dedicated to him. →]

Maria Scanu, after completing formal studies at the Art Institute of Oristano, refined her training in Florence under the guidance of sculptor Antonio Di Tommaso.

Her early period remained closely tied to subjective figuration. In her second phase, the object became increasingly essentialized until it dissolved into pure abstraction. This subjective interpretation of reality, leading to the poetic transfiguration of matter, can also be seen in her bronzes, where the image remains distinctly recognizable.

It is evident that in the works leaning toward so-called figurative exploration, there is a strong breath of spirituality and a metamorphic tension reminiscent of Ovidian transformations. A significant piece in this regard is Prossima, where the miracle of imminent motherhood is so tangible that it feels already fulfilled. Similarly, in L’abbraccio, physical union seems both to dissolve and intensify, merging and blending into a single act of love. Finally, in Eroina, one senses the drama of dependency on a hidden, inevitable affliction that appears to threaten the positive values of humanity.

It is precisely in this later period that a definitive break from objectivity occurs. A key transitional work is La Golfista, where the sculptor’s modeling intent reveals itself and is exalted through the emphasis on lines and volumes.

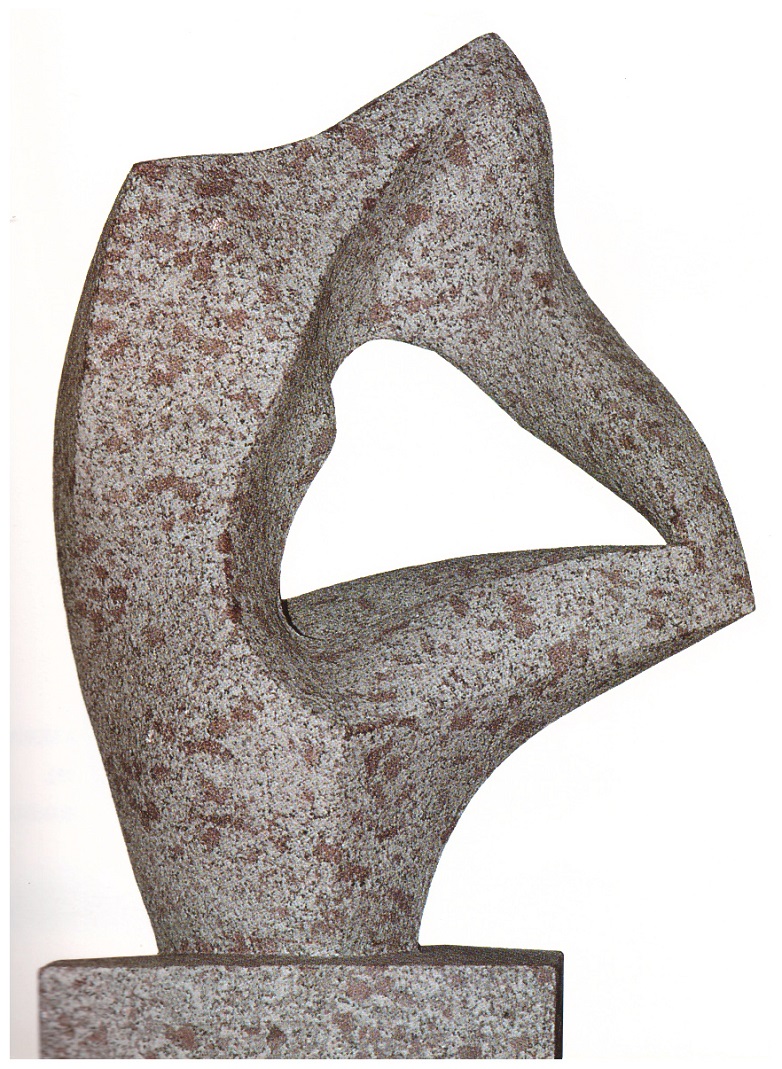

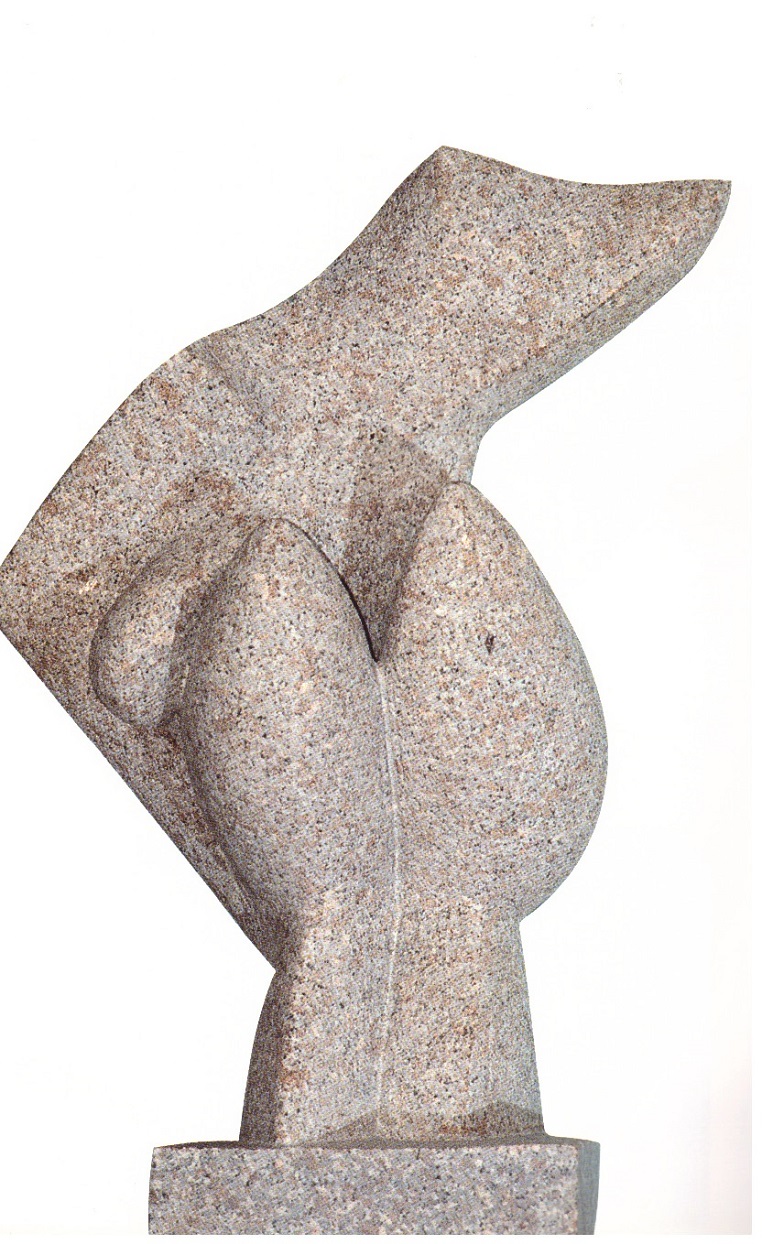

These lines and volumes take on a dominant role in subsequent works, where the attempt to achieve complementarity between form and space unfolds—a pursuit of pure essentiality entrusted to the rigor of geometric figures that still retain echoes of reality. This is evident in Insieme, Persona, and Donna, which, despite their free and abstract interpretations, still carry traces of the real, even if reduced to its most immaterial essence.

This essence reaches its peak in two of her most recent sculptures, Vibrazione and Omaggio ad Arp, where she achieves a remarkable balance of formal imagination.

One is inevitably led to reflect on the recurring dilemma: abstract or figurative? A dilemma that might be overcome—or even rendered irrelevant—if one considers that true works of art cannot and should not be confined within strict definitions.

Absolutisms are always harmful and should be avoided, as they lead to fanaticism. Who would dare claim that the enigmatic smile of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa does not contain the mystery of abstraction? Or, conversely, that in Lucio Fontana’s Spatialism, reality does not still pulse within the very cut made by the artist’s hand?

The Golfer (patinated bronze) – 1990

PLASTIC LANGUAGE AND AESTHETIC ISSUES

by Enrico Buda

[journalist and art critic, for decades a key figure in the cultural and artistic life of Venice →]

One of the most defining aspects of artistic research in this closing stretch of the millennium—one that is bound to assert itself in the early decades of the next century—is the internationalization of plastic language, along with the harmonization of all those aesthetic issues that were once considered to belong to distant cultural spheres.

Today, these elements exist within an awareness that leaves no room for delays in the coherent dissemination of an artistic platform capable of giving meaning to evolutionary proposals. This reaffirms the transcendence of expressions that once stemmed from complex movements but now highlight the distinctive contributions of individual expressive singularities, reaching their peak outside preordained circuits.

Beyond the historical and temporal reordering of plastic trends, these artistic endeavors establish themselves through their strong originality, personality, and the authenticity of emotions. This serves as a necessary introduction when transitioning from general to specific considerations, especially in attempting to outline a review of the current artistic landscape. Such an analysis must begin with those lines of research that no artist can escape and that strong-willed personalities know how to modulate in a way that ensures each composition integrates autonomously within the framework of modern cultural communication.

Within the realm of new plastic research, Maria Scanu undoubtedly occupies a precise and significant place, combining a powerful artistic vocation with an instinctive approach to sculpture. In all her works, instinct prevails; her material—even when it achieves the refined tones of a firm cultural foundation without succumbing to superficial formal sophistication—never relinquishes the vitality and energy that stem from her intense emotional charge, which “substantiates” her creations.

Maria Scanu’s artistic evolution is not just rapid; it is astonishing. In an incredibly short time, without traces of imitation or periods of apprenticeship, she has moved past the initial rawness and established a position that, while avoiding any avant-garde categorization, simultaneously remains true to an intrinsic aspiration for classicism. She manages sculptural space in its “in” and “out” to assert absolute forms of freedom, where even the torment of execution assumes stylistic significance, capable of conveying intrinsic qualities of persuasion.

Eager to absorb every artistic development and verify the data of her own nature and cultural heritage—on which she can always rely—Scanu embarks on a journey that spans from graphic studies of sculpture to works in clay, plaster, granite, marble, and bronze. She does so always in accordance with a language capable of satisfying the creative and emotional urgency that drives her. Thus, exercises, preparatory studies, and accomplished works emerge.

Certainly, in her sculptures, one can always sense the rhythm of a structured classicism that does not in any way hinder her already well-defined vision of sculpture as free from constraints. This vision reveals a clear and distinct concept of sensitivity—at times even extreme—which undoubtedly transcends the repetitive canon of the subject.

As a result, the predominant element in Maria Scanu’s work is the impulse of movement. It is a movement that is almost human in the theological sense of thought—carefully controlled, unfolding and developing as if following precise musical rhythms. It resembles a captivating and enveloping symphony, made up of sweeping curves and sinuous modulations akin to the lines of a youthful female body, experiencing only occasional sharp ruptures that nevertheless integrate seamlessly into the rhythmic harmony of a rounded and resonant expressiveness.

Sounds and signs interrupt space, and as they fall upon the forms, they also highlight precise and rigid angles.

The sense of harmony is alive and ever-present in her work.

Her volumes aspire to a vivid naturalism, veiling it with the myth inherent in ideological comprehension. However, alongside this, Scanu’s compositions reveal a spontaneity and craftsmanship that evoke arcane suggestions coexisting within the realm of ordinary things. At the same time, they consciously escape any form of didactic influence or aesthetic relationship.

There is no trace in her work of a call to or desire for a formal cataloging that might subtly manifest in mannerisms aimed at achieving a sought-after compositional grace. Her sculptures are born instead from the emotion of a form—or rather, from an idea of form—from an almost tangible desire to physically testify to sensations drawn from nature, but in their most absolute and complete a-physicality.

From her body of plastic studies, one can discern a uniqueness of proposals that neither should nor can be misleading, precisely because they are, first and foremost, allegorical sculptures. Smooth, full, compact volumes seem to rise upward, almost satisfied with their own instinctive energy, and present themselves as the foundation for the diverse characteristics of a pure and spontaneous language.

In her creations, with their broad curvilinear forms and sacrificial voids, a new dialogue between matter and the aspiration to an ever-fresh and vibrant spirit is anticipated.

One could simply say that, without ever renouncing the joy of an existence highlighted by mental processes aimed at the continuous renewal of artistic proposals, she does not hesitate to modify the tone and intensity, the compositional rhythm, and the structural themes of her creations.

By adopting her compositional approach, one can affirm that her evolving creativity—just as past examples demonstrate—confirms that her artistic journey is born solely from emotion, following a coherent balance between formal dictates and the conventions of common communication, always in visual respect for the image.

At any moment, whatever her idea may be, we are faced with a lucid discourse that seemingly requires no interpreters to be fully understood. Her bronzes, as well as her marbles and plasters, at times suggest iconic solutions, while rhythm, in turn, flows toward a-formal solutions under the guidance of a discipline that is, paradoxically, unmistakably formal.

It will be the voids—especially in works such as Donna No. 2 (1991)—that generate an almost ceaseless dialogue, where matter seems to dissolve to make room for the mental process that elevates sculpture to the primary means of penetrating the human soul.

MARIA SCANU: A Sculptor from the Sea

from

ARTE IN – volume 17, Numeri 89-91, Calcagni, 2004

“At times, I read fiction, especially biographies of artists: it is important to understand how, over time, other artists, like us, have faced the eternal and ever-new challenge of expression.”

Thus, even Maria Scanu—a sculptor of intense determination and great industriousness—sometimes sets aside her chisel. And in those moments, when she ceases to shape the forms envisioned by her intellect and sensitivity, when she briefly separates from her material—often the granite of Gallura (not her native land, but one she has intimately embraced by choice)—she willingly entrusts her mind to the pages of books.

Perhaps it is from these readings that her particular manner of speech derives, with words that are mature, measured, and carefully weighed. It is no coincidence, then, that Maria Scanu says “expression” rather than “representation,” emphasizing that for an artist, the challenge is not to copy but to interpret. The ideal observer of her work—almost like the “exemplary reader” of the visual and plastic text she has written and continues to write through her sculptures—is not the one who asks, “What does this work mean?” but rather the one who perceives and affirms, through sight and senses, the emotion of the piece.

We begin in this way, drawing also from the artist’s own voice, because in Maria Scanu’s words, we perceive not only a trustful openness to engaging with the viewer’s gaze but, above all, a significant declaration of artistic philosophy. This is all the more essential to understanding the work of an artist whose biography might seem, at first glance, full of deceptive traps—easy to misunderstand and reduce to clichés. However, its deeper meaning is something else entirely.

The first antithesis may appear all too simple: on one side, her native Sardinia; on the other, the mainland—as if the former were entirely defined by “nature” and the latter by “culture.”

But the Oristano of her childhood and youth was not just an enchanted world of gardens and fish-filled lagoons; it was also the passionate attendance at the Institute of Art, as well as the powerful presence (not generically “Sardinian” but rather deeply specific to that locale) of important, stratified memories, histories, and cultures. There were urban landmarks of medieval and Romanesque origin, alongside scattered remnants of Nuragic, Punic, and Roman civilizations—ancient yet continually reshaped, daily renewed by the profound light of a Mediterranean turned toward the West.

As for Gallura, where Maria Scanu now primarily lives and works, it is quite distinct from the Campidano of her early years. If vegetation reigned supreme in the latter, here it is the mineral world that dominates—a microcosm of rock and granite that demands experience and fosters familiarity. Yet, it would be equally mistaken to mechanically translate this physical environment into a mere source of “inspiration.” The granite matters inasmuch as it becomes the “chosen instrument” of the artist’s will—one she skillfully renders soft, malleable, and luminous, qualities all deeply embedded in her expression.

And what of the mainland? For her, it was primarily Florence. A place of exchange and dialogue with local artists and critics, meritoriously loyal to the enduring humanistic tradition and its “refinement.” This experience was dear to the sculptor, not only for the technical refinement it entailed but also (and this may seem paradoxical) for the artistic contrast it provoked. Indeed, within the ostensibly raw and primal “nature” of her island origins lay, in potential, a fully formed “culture.” And this culture awaited only the moment of articulation—through contrast and dialectic (never through polemics)—to become fully aware of itself and to emerge into the light of its own artistic responsibility.

Faced with the “fullness” of Florence’s academic tradition, Maria Scanu developed and opposed to it a different sense of plasticity—her own, which had been maturing and awaiting her for some time. Flowing, soft, caressable figures, echoes of an “eternal feminine,” not autobiographical but chosen, sought, and embraced. Figures that often feature grooves or “voids,” expressly designed to be traversed by light and to assume a different consistency—features that are anything but a subtraction of space or form. Rather, they are matrices offered to the gaze, so that from the encounter, a new reality of expression and emotion is born.

Regarding her works, the sculptor points out that even their titles, far from indicating absolute references, serve instead as suggestions or invitations to the viewer. Similarly, the names of Moore (to whom Maria Scanu dedicated a heartfelt sculptural Homage) and perhaps even more so that of another great Tyrrhenian artist, the Viareggio-born Viani, signal affinities rather than genealogies or hierarchies.

Just as Maria Scanu poetically transcends the tyranny of subject matter and its mimetic verification, so too does she distance herself from any acquiescence to avant-garde myths of decontextualizing the artwork or even of the “open work.” Instead, she operates within the humanistic principle of shared experience.

Thus, when she chooses not to define the facial features (or virtuously drape the mantle) of the monumental and celebrated Madonna del Mare in Santa Teresa Gallura, she does so to pursue unity and communion through an archetype that exists beyond appearances. The benevolent and protective evocation of this towering presence, achieved through the symbolic shaping of granite into a mandorla of light, is both archaizing and refined—almost iconically Byzantine in its intent.

The trap of biographical clichés may not yet be exhausted; much could be said, for instance, about the relationship between Maria Scanu’s mature artistic calling—her productive otium—and the years she dedicated to non-artistic professional experiences, her negotium. But the answer, the decisive leap beyond clichés, always lies within her work, speaking to her fundamental purpose through the expressive language that is uniquely hers.

If it is true that “plastic force has its roots in justice” (as Hugo von Hofmannsthal once wrote), then we can finally recognize, within a living ethical sense—not to be confused with a cold, disembodied, and asensory moralism—the foundation and the culmination of Maria Scanu’s joyful and fervent artistic endeavor.

OTHER BRONZE SCULPTURES

GRANITE SCULPTURES

MARBLE SCULPTURES

THE MADONNA OF SEAFARERS

of Santa Teresa Gallura

The Madonna of Seafarers in Santa Teresa Gallura is Maria Scanu’s most renowned artwork. The sculpture was inaugurated in 1999 and stood there for twenty-two years—beautiful and maternal, discreetly positioned beneath the town’s famous tower, facing the sea and the sailors—until, in 2021, a post praising it appeared on the popular Facebook page Sardegna Che Passione: “Santa Teresa Gallura. The artist who created this beautiful granite artwork is the talented Maria Scanu. The title of the piece is Madonna of Seafarers.”

Accompanied by a striking photograph, the post turned the statue into a viral sensation on social media, drawing the attention of major Italian and even international newspapers and websites. For many commentators (as of now, the post has received 11,688 reactions, 4,206 comments with thousands more reactions, and 15,406 shares), the Madonna was seen as essentially resembling a female vulva. To some, this made the sculpture scandalous, even offensive. (Over time, the engagement on the post has declined, possibly indicating a shift in perspectives.)

One particularly interesting response came from the American website Fem Catholic, which published an article titled Celebrating Mary’s Birthing Body This Christmas. The platform, whose mission states, “We believe the greatest untapped resource in the world, and in the Church, is women,” reflected the international resonance of Maria Scanu’s work. Beyond simply echoing the global discourse surrounding the statue, the article stands out as a thoughtful, reflective, and culturally rich piece—one well worth reading and contemplating.

Celebrating Mary’s Birthing Body This Christmas →

december 22, 2021

Over the summer, this statue of the Virgin Mary by Maria Scanu went viral on Reddit, as people discussed whether or not it was intentional that the statue resembled a vulva. While we don’t know the artist’s intent, there is plenty of Christian tradition to support that the statue could have been designed that way on purpose.

Looking through the comments, you see a variety of opinions: there are some jokes being made, some people who are uncomfortable discussing female body parts (including the first comment that uses the phrase “lady bits”), some people who appreciate that the design both looks like a pregnant Mary and like a vulva, and some people who have to educate others on what exactly a vulva is. The assumption is that female body parts are gross or taboo, and that no one associated with a Church that emphasizes purity could possibly have intended to celebrate them.

Discussing the female body in the early Church

The exchange on Reddit reminded me of documents I read from the early days of the Church, when theologians debated Christ’s humanity. Even then, some theologians wanted to present the female body as too dirty and gruesome for God to emerge from. In one exchange, a theologian named Marcion stated his belief that the process of birth was unsuitable for God, and Tertullian of Carthage (also a theologian) defended it. He outlines Marcion’s complaints against the process of birth:

“…the filth of the generative seeds within the womb, of the bodily fluid and the blood; the loathsome, curdled lump of flesh which has to be fed for nine months off this same muck. Describe the womb – expanding daily, heavy, troubled, uneasy even in sleep, torn between the impulses of fastidious distaste and those of excessive hunger…” (On the Flesh of Christ)

Tertullian, however, said that the human body is inseparable from the rest of the human person, that God redeemed all of us, and that “He would not have redeemed what He did not love.” Ultimately, the Church sided with Tertullian – and declared Marcion a heretic.

This disagreement in thought about the female body seems to still exist in different forms today, but there are plenty of examples in Christian history of yonic artwork that celebrated the female body. Early Christians built vulva-shaped baptismal fonts like this one to celebrate being born into new life in Jesus, and medieval artists painted Jesus’s side wound in a yonic way, since it also produced new life as it released blood and water.

If, in fact, Maria Scanu did intend for her statue to resemble a vulva, her choice ought to be celebrated, rather than ridiculed. The vulva is the strong and flexible organ that pushes life into the world. And in Mary’s case, it is the means through which Jesus was brought to earth. If that idea is shocking, that is a good thing, because it helps us remember how truly momentous it is that God took on human flesh and was born to a young woman in Nazareth.

Remembering Mary’s side of the Christmas story

This Christmas, just five months after giving birth to my first child, I am trying to focus more on Mary’s experience the night that Jesus was born. The nativity story skips quickly from the tale of pregnant Mary riding on a donkey to baby Jesus sleeping in the manger, but any woman who has given birth will tell you that is not how it happens. Each year, we celebrate Jesus entering the world and taking on messy and fragile human flesh, which was entirely reliant on the blood, sweat, and tears of his mother’s laboring body.

When Christ was laying in the manger, she was still bleeding and aching, without the comfort of a hospital bed or pain killers. She was likely still recovering emotionally from a process that had a much lower survival rate than it does today, and the usual stress of assuming responsibility for a new person must have felt even heavier when that baby was an unexplained miracle. I imagine she was exhausted but couldn’t sleep, interrupted every few hours having to feed the baby Jesus, her nipples feeling the pain of that new experience.

It was because of Mary’s strength and resilience that Jesus was pushed into the world, nourished once he arrived, and loved as he grew. When I look at my nativity scene this Christmas, my eyes will linger a little longer on her figure, wonder why she doesn’t look a bit rounder and more exhausted. But mostly, I’ll be grateful that because of her birthing body, God came to be among us.

THE WAR MEMORIAL

of Santa Teresa Gallura

The granite War Memorial of Santa Teresa Gallura, also known as the “Monument to Peace,” was solemnly inaugurated on Saturday, November 5, 1994. It was created to partly replace an earlier, more ancient monument. From a 38-ton block of granite sourced from the Luogosanto quarries, Maria Scanu sculpted a 3.6-meter-tall statue weighing 18 tons. At the base of the monument, a flame unfolds, an allegory of sacrifice and martyrdom.

Art critic Luciano Caprile described the monument in the official press release issued by the Municipality for the inauguration:

“To bring the discourse onto the terrain of sacrifice—without abandoning that seed of traditional figuration so deeply rooted in Scanu’s work—some figures emerge, barely sketched and shielded by tongues of fire, a refuge from suffering, a resting place that transforms death into the sleep of the righteous. The meaning of martyrdom is further emphasized by the distinct texture of the base, roughened at the points where the figures appear, as if suffering itself has seeped into the ground. It is a detail meant to be perceived perhaps more by touch than by sight, a signal that allows us to access the artist’s profound sensibility.”

LA FONTANA IN BRONZO

a SASSARI