AT THE COURT OF AGA KHAN

MEMORIES OF THE COSTA SMERALDA

by PAOLO RICCARDI

Interview by Mabi Satta

With the kind permission of the publisher Carlo Delfino, we are publishing an extensive excerpt from the book

On the back cover

It is an unedited piece of Sardinian history

Presentation for Gallura Tour by Guido Rombi

POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE COSTA SMERALDA FROM 1963 TO 1982

KARIM AGA KHAN IV AND HIS COSTA SMERALDA AS TOLD UP CLOSE

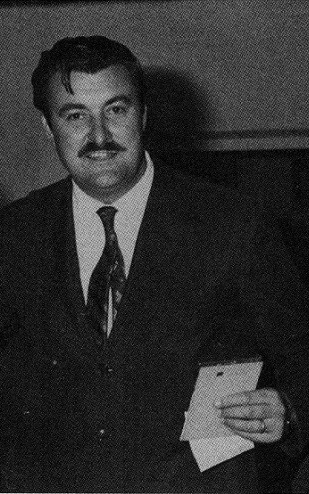

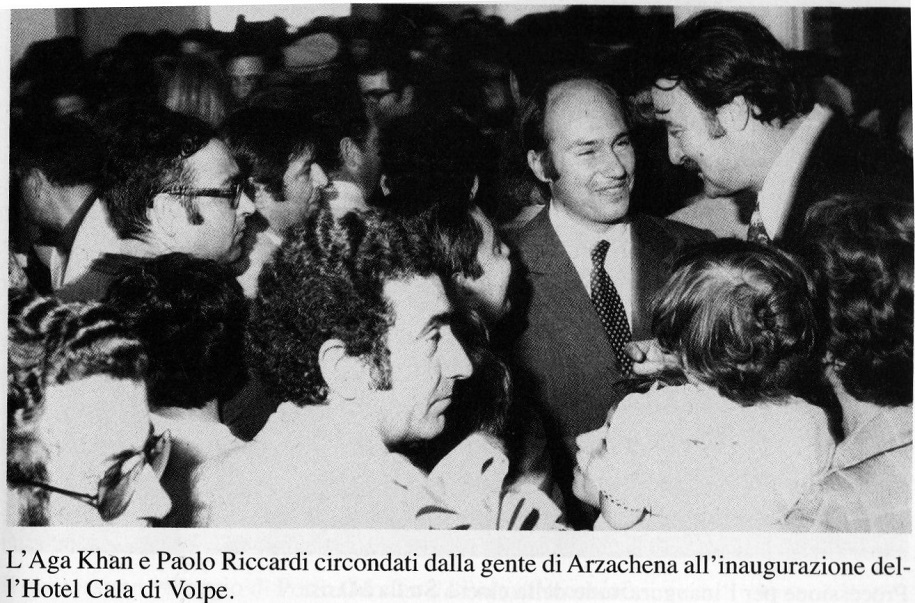

Reading this book carefully, I could not help but add to the official title two alternative ones that immediately convey more to the reader about “what” they are going to read. In this volume, lawyer Paolo Riccardi – who was the Secretary General of the Costa Smeralda Consortium and President of all its companies – is interviewed by his longtime secretary Mabi Satta. He primarily reveals the political struggles and their behind-the-scenes maneuvering between Arzachena, Cagliari, and Rome for the realization of the incredible and unique tourism project known as “Costa Smeralda”. Likewise, he unveils the governance dynamics of Costa Smeralda from its inception until almost the exit of Karim Aga Khan IV, with the Prince always remaining the absolute dominus in the final instance.

What stands out in these memoirs is that the journey was far from a bed of roses or lavish red carpets for one of the most extraordinary tourism ventures in the world. Quite the opposite.

It is thought-provoking that, except for the first nine years (1961-1970) – a period in which Porto Cervo, with its hotels, villas, exclusive multi-level homes featuring staircases, terraces, and arches, its square and old port, and the renowned super hotels designed and directed by extraordinary architects, rapidly took shape – the primary opposition came from the municipal administrations overseeing Costa Smeralda, the paradise chosen by the Aga Khan, namely Arzachena. Occasionally, they were supported by some regional governments. Indeed, the residents of Arzachena, who owned lands in the surrounding areas of Costa Smeralda (Baia Sardinia, Cannigione, Laconia, Poltu Quatu, Portisco, etc.), quickly realized the great fortune of possessing those rocky and fragrant Mediterranean scrublands near the sea thanks to Costa Smeralda itself. They were Sardinians, native Gallurese, and while they did not have the billions of the billionaires, they did possess a weapon that the wealthy did not: the right to vote. They elected the municipal council and thus indirectly their administrators; in short, the political-administrative power of the municipality was heavily influenced by them. As a result, starting in the early 1970s, the Consortium’s requests for new building volumes faced growing opposition, as they needed to be at least partially shared with the demands of the native residents in the surrounding areas, which were equally beautiful, such as Cannigione, Baja Sardinia, and Portisco.

Note: Perhaps too much and for too long, attention has been given to the native inhabitants who, when the first foreign and continental magnates arrived, not understanding the economic value of money or the tourism potential of their land, insisted that sales negotiations discuss millions instead of billions. While some may have sold at prices later considered “a gift” (which has always been the case in transactions involving unknown value assets), it is certain that, in a short time, those initially poor locals who inhabited those lands (not to mention the wealthier townspeople of Arzachena) awakened from their “naivety” and “removed the ring from their noses.” Not only that: a significant portion underwent a rapid course of economic and professional training by observing “the Aga Khan school,” becoming artisans and self-employed entrepreneurs, with many reinvesting their capital in waterfront real estate developments adjacent to Costa Smeralda, and many feeling like “little princes.” The arrival of the Aga Khan and the subsequent coastal tourism development not only transformed the Sardinian coasts and Sardinia in general but primarily transformed the Sardinians of those lands. This story, I believe, still requires significant socio-economic and anthropological investigation.

New and unprecedented challenges gradually arose for the Municipality of Arzachena and the Region of Sardinia over time. What was granted to the Costa Smeralda Consortium—villas or hotels just a stone’s throw from the sea—would inevitably have to be granted to all new applicants as well. The Municipality of Arzachena, like many other coastal municipalities in Sardinia, soon found itself overwhelmed by requests for construction, driven by the extraordinary and unprecedented tourism enterprise. However, not all the new “developers” bore the name Aga Khan, not all urban planners and architects were named Vietti and Couelle, and not all buyers possessed the wealth of the first Costa Smeralda holidaymakers.

The risks to the coastline and landscape—both environmental and scenic—became increasingly significant and potentially disastrous. Lawmakers inevitably had to address these issues and step in to regulate. And it was no easy task. Introducing urban planning laws that imposed consortia, architectural committees, and stringent regulations for property owners, as was done in Costa Smeralda, would have sparked an uproar: it would have been perceived merely as a way to favor continental and foreign billionaires at the expense of the Sardinians. Politics—especially that of the mass parties of the 1970s and 1980s, which were highly participatory and militant—could not afford such a stance.

Thus began the political and administrative challenges that would soon accompany the “fairy tale” of Costa Smeralda from the early 1970s onwards. It is no coincidence that the beautiful Porto Cervo, along with all its most famous hotels, was developed in the 1960s in a sort of “vacatio legis.”

The many and repeated political and administrative difficulties that arose from the early 1970s—especially at the local and regional levels—regarding the general development plans of the Costa Smeralda Consortium, gradually accompanied by even adverse press campaigns, ultimately proved fatal in Karim Aga Khan’s decision to leave Costa Smeralda and Sardinia.

And now we come to Karim Aga Khan himself. This interview-book by Paolo Riccardi—one of the key figures of Costa Smeralda, the lawyer who stood by the Prince’s side for twenty years in the realization of this incredible tourism project—is invaluable in providing a closer look at the personality of the Prince during his younger years (between the ages of 27 and 46).

There are no other books or essays that portray his figure, his character—both strengths and weaknesses—with such proximity and sufficient depth. The Aga Khan is depicted throughout many pages, even in those not explicitly dedicated to him, through anecdotes, curiosities, and behind-the-scenes accounts—many of them amusing and entertaining, yet all fascinating.

They reveal a Prince who was enthusiastic about his tourism project, dedicating himself to it day and night, an exceptionally hard worker, an inspiring leader who motivated the workforce to multiply their efforts to quickly bring to life that “royal dream” which they also regarded as their personal pride. However, the accounts also reveal a Prince with a complex character: in personal relationships, at times overly distrustful, suspicious, and touchy; at other times, overly magnanimous, bringing into his circle individuals whom his secretary had advised against (and who regularly ended up failing). But most notably, he was often stubborn and not very inclined to compromise in political and administrative dealings, opting instead for an “all or nothing” approach.

Yet, in a way, the Prince can be understood: with an Anglo-Saxon background and a managerial rather than political mindset, despite being assisted by a man as shrewd, skilled, and socially connected as Paolo Riccardi —who was chosen precisely for these qualities—he struggled during his younger years to navigate the intrigues and machinations of Italian politics. In certain crucial moments, he should have been more flexible, more willing to settle, and above all, more trusting of his advisor (a personal regret that clearly emerges in these memoirs).

In short, Alla corte dell’Aga Khan. Memorie della Costa Smeralda is a truly fascinating book, recommended not only for scholars and enthusiasts of Sardinian history. These memoirs of the political and administrative history of Costa Smeralda and Sardinia are also rich in amusing, ironic, and sometimes surprising behind-the-scenes insights, as well as notes of glamour and gossip about the “Emerald Court” and other “courts” (particularly in the eighth and twelfth chapters).

A great deal of credit goes to his long-time secretary, Mrs. Mabi Satta. She became his secretary in 1966, having been encouraged to relocate from Rome where her family had lived for years. It was she who urged Paolo Riccardi to publish this invaluable memoir and structured it through a long series of interviews, ultimately presenting it to the well-known publisher Carlo Delfino of Sassari.

Perhaps out of an excess of discretion and confidentiality, Mrs. Satta’s name does not appear in the Italian version of the book (one “gap” being that it is not clear who is posing the questions to lawyer Riccardi). However, her name is appropriately included in the English edition published in 2013, where she is assisted by her husband, Laurence (Lorenzo) Camillo—another key figure who actively contributed to the incredible Costa Smeralda tourism enterprise. He authored one of the introductions and helped refine the translation.

Thanks also to the interview format, Paolo Riccardi’s memoirs are easy to read and highly enjoyable—making it a book that never bores and keeps the reader intrigued from the first to the last page.

A Little Prehistory

Presentation di Laurence Camillo

The ancient territory which would eventually become the Costa Smeralda was virtually uninhabited up until two centuries ago. The part which goes from Piccolo Pevero to Liscia di Vacca and Poltu Quatu was difficult to reach by land, surrounded as it was by steep mountains, covered with an impenetrable forest and impregnable rocks. And, naturally, without any roads. However, it was an enchanted valley, rich with game and fishing, with a splendid coast and jagged cliffs looking out on limpid turquoise waters. During antiquity, at Arzachena instead, there was a significant presence of people, in a tiny village some 15 kilometres inland, some of whom most likely occasionally ventured out to the coast.

Sardinians generally feared the sea, above all during medieval times, when pirates, who had always threatened this land, multiplied their raids. Monte Moro, which towers over Porto Cervo, takes its name from its function as look out point against the “Mori”, the dark people. As a result, people settled far from the coast, in the “stazzi,” small country cottages built of granite which blended into their surroundings, but placed in areas invisible from the sea.

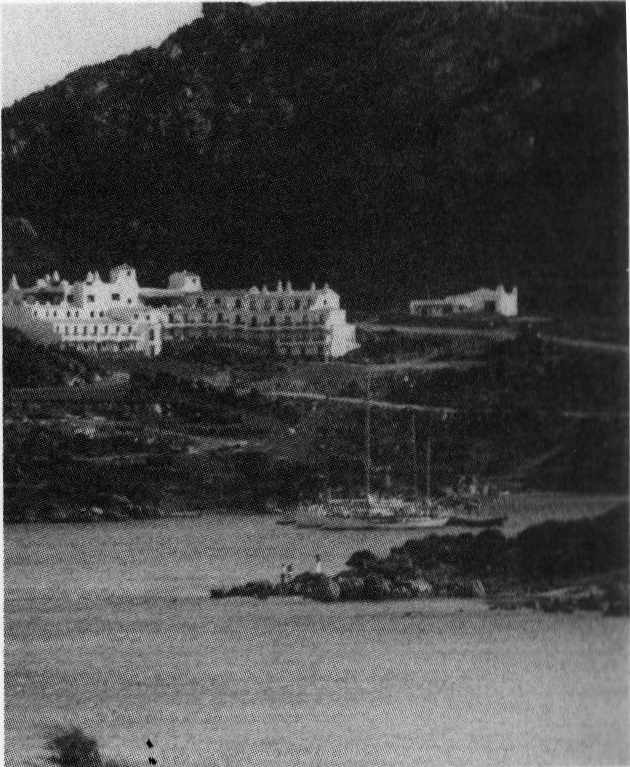

The marvelous bay of Porto Cervo remained in its natural state for centuries; not even a fisherman’s cottage interrupted the landscape, for there were no real fishermen in Sardinia. Families of professional fishermen arrived only recently in Gallura, from the island of Ponza, and settled here, like the Avellino family, who made their home at Abbiadori. Occasionally, the inhabitants of the village of Arzachena would go to the coast to hunt or fish, but they found it easier to arrive at Battistoni (today named Baia Sardinia), at Cala di Volpe and Capriccioli, which were more easily accessible.

The first permanent inhabitants of the area were five Corsican Brothers named Orecchioni, arrived in the early nineteenth century. They settled at Liscia di Vacca, where they began a prosperous smuggling operation in salt, sugar, and gunpowder. Their motives for leaving Corsica are unknown, but they were happy in Sardinia and remained there. Memories are still vivid of the incredible noise made when one of the brothers’ considerable deposit of gunpowder hidden in the Conca di Maracca exploded. That same Conca di Maracca, a large cave under the rocks along the curves of the Liscia di Vacca road, served as a hiding place from pirates up until recent times, as recounted by Gavina Orecchioni, the mother of Zio (uncle) Battista.

The inhabitants of Liscia di Vacca slowly increased in number, forming the small hamlet that can be seen today, where they built the first church of the area. They planted wheat at Cala Granu, from whence its name and took their flocks and herds to graze at Liscia di Vacca, “the cow’s meadow”. To reach the mill in Arzachena, they had to go by oxcart, taking a long and bumpy road called a ruccatogghju, opening and closing a series of fifteen gates one by one. Maria Orecchioni went to school in La Maddalena on board a water tanker boat which carried water, loaded at the jetty of the Baia Sardinia, to the inhabitants of La Maddalena.

Tuscan woodsmen arrived as well, to cut down the beautiful woods and slowly burn its logs, in pyres, transforming them into charcoal: traces of their activity can still be seen in the clearings on the slopes of Monte Moro. Sadly, the great oaks and juniper trees of old are almost all gone.

At Abbiadori, the Azara settled and formed another small hamlet of shepherds, who grazed their flocks and herds in the area of Cala di Volpe and even on the islands. “Uncle” Battista Azara used to tell the story of how on his little boat, he used to accompany the dairy cows, which would swim all the way to the island of Mortorio. These inhabitants were not poor; they had a good life and they were happy in their little earthly paradise. They would organize picnics under the trees in various places, which were occasions for young people to meet, to get engaged, and to settle down to raise a family.

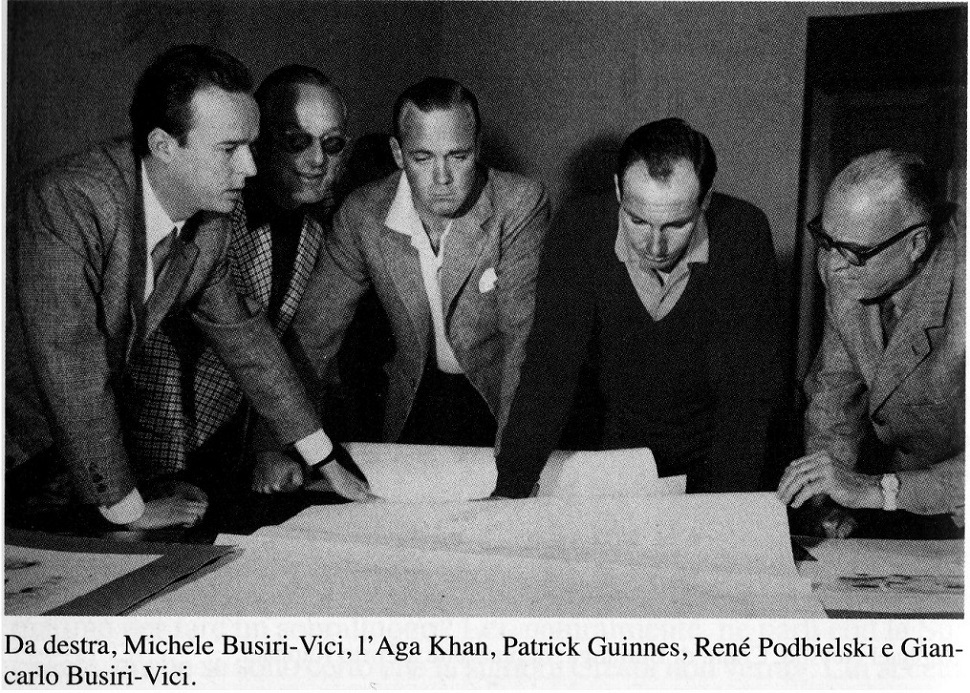

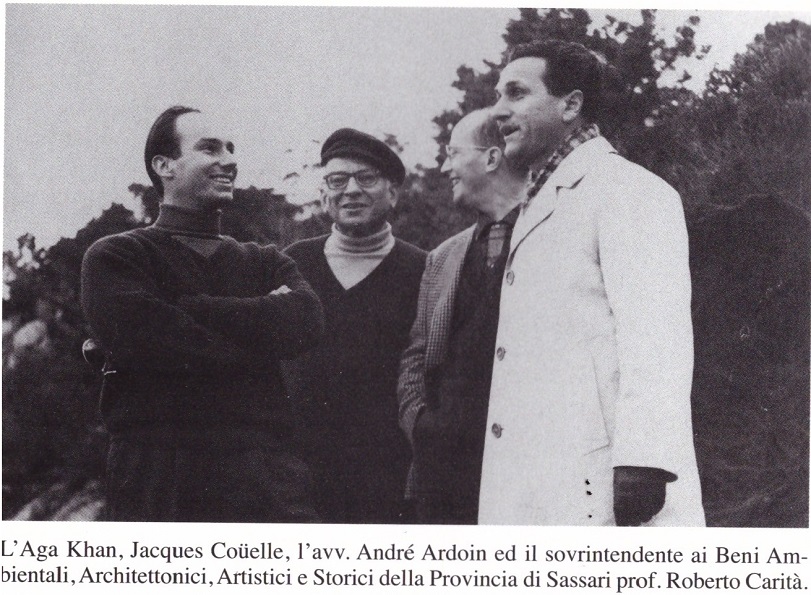

Then in the 1950s the first yachts began arriving, such as the famous Croce del Sud of Mentasti, who began purchasing land at Porto Cervo, the Podbielski at Liscia di Vacca, the young Aga Khan at Pevero, Romazzino, Razza di Junco and Cala di Volpe, his half-brother Patrick Guinness at Liscia Ruia and “Punta Guinness,” André Ardoin at Pantogia, Pitrizza, Capo Ferro and elsewhere, Duncan Miller at Capriccioli etc.

A Consortium (Consorzio Costa Smeralda) was founded in the spring of 1961. The “spiritual guide” of the organization was the Aga Khan, who overlooked the whole process attentively, calling upon leading consultants and the most famous architects of the world. He was a real estate developer with a fifty-year investment plan, something unique in Italy and perhaps in the world. Locally, he entrusted the political preparation of the project to a young lawyer from Sassari, Paolo Riccardi, a giant of a man, both in physical stature (6 foot 8) and in diplomatic skills. He was a family and school friend of important men of politics, such as Antonio Segni and Francesco Cossiga, future presidents of the Republic of Italy, and Enrico, Giovanni and Sergio Berlinguer, as well as of many important figures of local regional importance.

During the very first years of the Costa Smeralda, the real estate developers led by the Aga Khan were well regarded by the local authorities and they did not run into bureaucratic obstacles in the realization of their projects, be they hotels, villas or residences. The president of the Region at the time, Efisio Corrias, and the mayors of Arzachena, first Giacomino Tanchis and later Giorgino Filigheddu, were inclined to favor these investments, in which they recognized a new possibility for economic development in an area which was still primarily agricultural. The high regard in which the young Prince Karim was held was so pronounced that in 1966 the municipality of Arzachena bestowed honorary citizenship upon the Aga Khan and whatever construction permits he requested, were immediately granted.

In the latter half of the fifties, instead, a group of “rebels” formed within the Democrazia Cristiana, led by Francesco Cossiga, jokingly nicknamed “The Young Turks.” The group included Pietro Soddu, Paolo Dettori, Nino Giagu de Martini, Piero Are and many others, and one of its adherents was Gian Michele Digosciu of Arzachena. They formed an opposition to Segni and his nephew Nino Costa, upon whose help the group of the Aga Khan had always counted. When he was named provincial secretary for the party, Cossiga took control of the Sassarese DC; that group would dominate the political scene in Sardinia for the next twenty years, over time occupying all of the political appointments available, alternating amongst the regional presidency, the provincial ones, the councilships and the direction of almost all of the bureaucratic apparatus on the island, forming a formidable compact political group.

During that period, the large petrochemical industries also landed on the island, including Nino Rovelli in the north and Angelo Moratti in the south, to take advantage of the huge State financing opportunities designated by the Funds for the South. In this way, industrial mega-plants were born, such as Saras at Sarroch on the gulf of Cagliari, and SIR at Porto Torres.

For their part, the Sardinian politicians looked favorably upon these industrial initiatives, which allowed them to take the backwards countryside out of the Middle Ages and produce a higher quality of life. But there was another reason for their support as well: industrial workers were far more unionized than farmers, and therefore more easily influenced when it came to politics. In other words, they represented a huge block of potential votes, easily swayed.

In short, the group of the “Young Turks,” influenced especially by Soddu, a great believer in the industrialization of Sardinia, preferred to sustain and support large industry rather than the new and still nebulous tourism industry that was was just beginning to appear in Gallura. They therefore began to attack the plans for expansion that the Aga Khan had for the Coast. One of the key battles in this war was the election of Digosciu to the office of mayor of Arzachena.

This mayor found quick support in the regional council when it came to blocking the Aga Khan, and therefore all of the projects presented by the Costa Smeralda were systematically rejected.

To approach the “Young Turks” and manage to convince them of the promise the tourism industry held for the population overall was a protracted job requiring astuteness and patience, which was carried out by Paolo Riccardi. Luckily among the “Young Turks” there were some (Cossiga, Giagu, Are and Soddu) who had been his high school and university classmates in Sassari. With great difficulty, Riccardi eventually managed to convince them and obtain approval for all the allotments and the constructions which we may see completed today on the Costa Smeralda.

Riccardi’s work was, however, interrupted in 1982, upon the severing of relations with the Prince, and he was therefore unable to obtain the approval of the so-called “Master Plan” for the completion of the Costa Smeralda. This part of the plan involved the land stretching from Cala di Volpe to Portisco, and included three new golf courses. Its realisation would have achieved a stable residential community which would have permitted the Costa Smeralda to live all year round, instead of only during the current brief seasonal period.

This defeat contributed to the Aga Khan’s disengagement and then definitive abandonment of the control of the Costa Smeralda Consortium. Exasperated, the prince ceded his role to the American Sheraton company, which was later absorbed by Starwood, which was subsequently taken over by Colony Capital and recently by Qatar Holding. The prince retained “Alisarda” which in the meantime had been renamed “Meridiana,” as well as the Costa Smeralda Yacht Club and a home at Porto Cervo.

The reminiscences of Riccardi give us an indication of his herculean efforts and a glimpse behind the scenes of the negotiations, opening a window on the Sardinian and Italian political situation of those years.

INDEX

The original titles of the paragraphs (see HERE) have been integrated/clarified in square brackets; and sometimes new ones have been added.

The paragraphs marked with a bullet point are available for reading; for the full edition, see HERE ⇒

1. A HIDALGO NAMED RAPHAEL (see HERE ⇒)

Before the Aga Khan

The beach of his dreams

The calculations of the Romanian banker

The hidalgo and the President

The grapevine effect on the English nobility

A pocket with a hole and a guardian angel

People at the seaside

The house nude

Plans for tourism. [The Exhibition and Conference in Alghero] •

«We have an urgent need». [The Establishment of the Alisarda Company] •

[Skill and Connections: A Phone Call to Paris and Consulting on Sardinian Industry and Agriculture] •

Liscia Ruja and Rena Bianca. [The Clash with the Ragnedda Brothers] •

The third act. [The Aga Khan and His Brother Patrick Guinness Propose to Paolo Riccardi to Oversee the Costa Smeralda Project] •

A wrench thrown into the works. [The “Young Turks,” an Internal Political Faction of the Christian Democracy Party in Sardinia] •

From the hill of Porto Cervo. [September 1963: Planning the Village and the First Port] •

Honorary citizenship. [The Mayor of Arzachena, Giorgino Filigheddu, Grants Aga Khan Honorary Citizenship] •

A man who had time for everything. [Aga Khan: A Tireless Prince] •

Mr. Ardoin and the irrepressible prince •

The “Alisarda” •

«You see, Romiti» •

Landing with the sheep •

A friend in the government. [Salvatore Cottoni; Alisarda Faces Opposition from Alitalia] •

It was called Venafiorita. [The Olbia-Costa Smeralda Airport is Established] •

Nordio comes to the rescue. [The Request to the Alitalia President for the Cagliari-Milan Route: Problems and Clashes] •

We’ll even talk to the communists •

Looking for other routes. [Alisarda Expands] •

A photo on horseback. [Kenya and Tanzania Sell the First Planes to Alisarda: Sir Pirbai, the Mediator of the Deal with Kenya; Adjabali Kassan, the Only Ismaili Allowed at the Aga Khan’s Court in Costa Smeralda] •

The party membership card. [Paolo Riccardi Joins the Communist Party: A Membership Card to Use at the Right Moment] •

5. THE PORT, THE WATER, THE STREETS ⇒

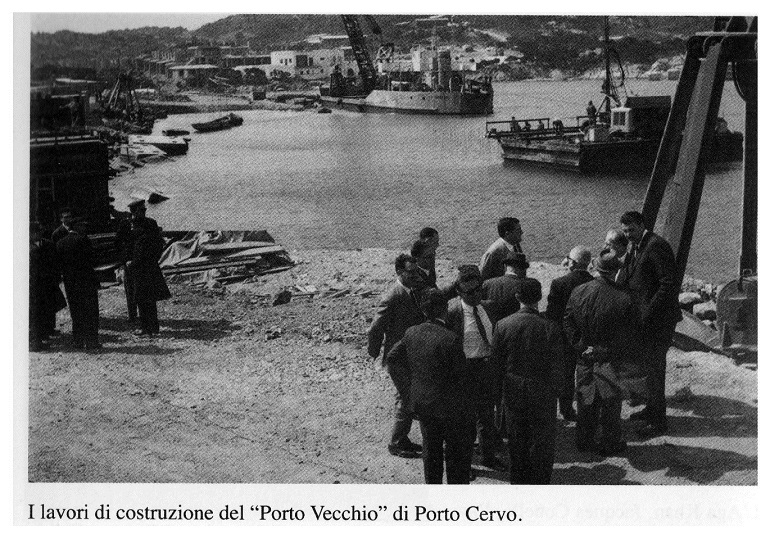

The Old Port. [[The Difficult Relations with Commendator Ghiglia, Director General of the Ministry of Merchant Marine, for Authorization to Build the First Private Tourist Port – The Unauthorized Construction Work – The Suspension and Subsequent Resumption of Work – The Aga Khan Bans the Invitation of Regional Politicians to the Inauguration.] •

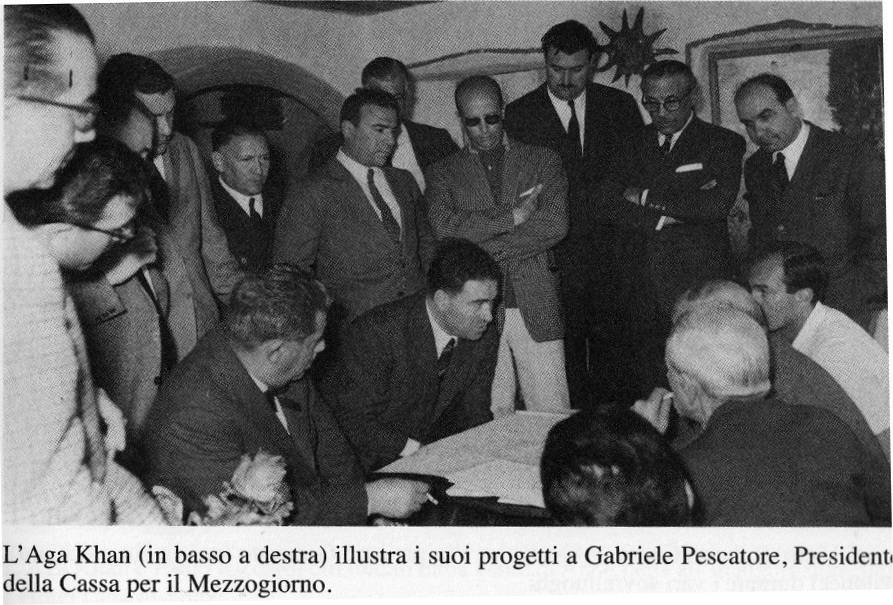

Funds for the South. [The Road Issue. Christian Democrats Against Christian Democrats: Minister Pastore Issues an Ultimatum to Provincial President Michelino Corda] •

The shoe with a hole. [The Aga Khan Visits Minister Pastore with a Hole in His Shoe] •

The landless prince. [Honorable Raffaele Garzia, First President of CIS – Sardinian Industrial Credit and a “Friend” of Costa Smeralda; Later President of Etfas and Hostile to Costa Smeralda. Personal Resentments Affect His Public Administration in Water Supply Projects] •

The new companies. [Biancasarda; Cerasarda] •

The story of “Acquasarda”. [Dr. Ventura and the Dowser Martino Azara]

A little triumverate •

André Ardoin, Esq. •

Mr Felix Bigio •

Mr René Podbielski •

Doctor Mentasti •

Doctor Peter Hengel •

Patrick Guinness •

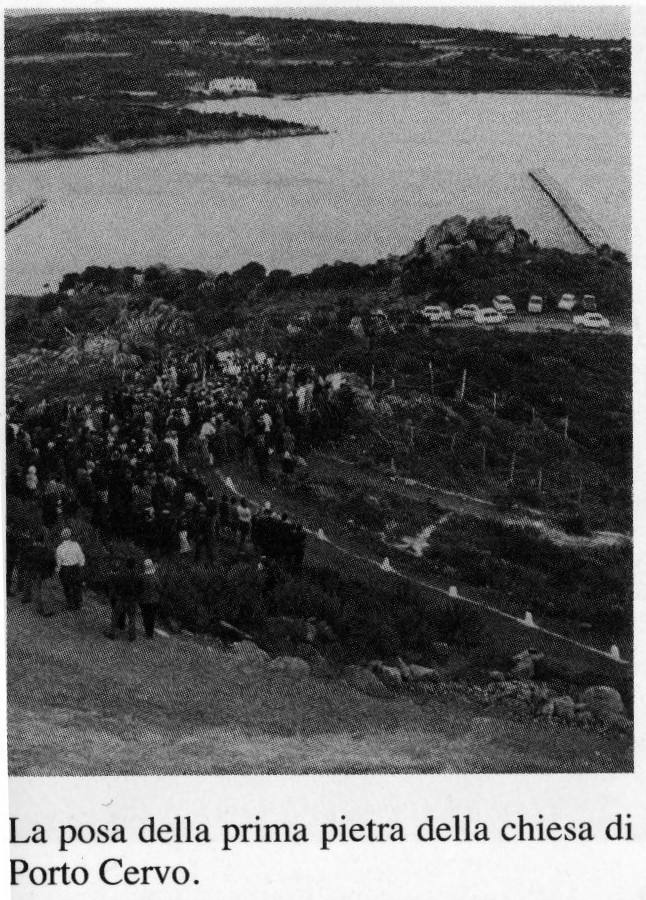

The “rich man’s priest”. [Fr Raimondo Fresi] •

Pino Careddu, a friend [and His ‘Farewell’ to Lawyer Ardoin] •

7. THE ARCHITECTS OF THE COAST ⇒

The Architectural Committee

[Jacques Coüelle resigns from the Committee due to disagreements with the Aga Khan]

[Savin Coüelle]

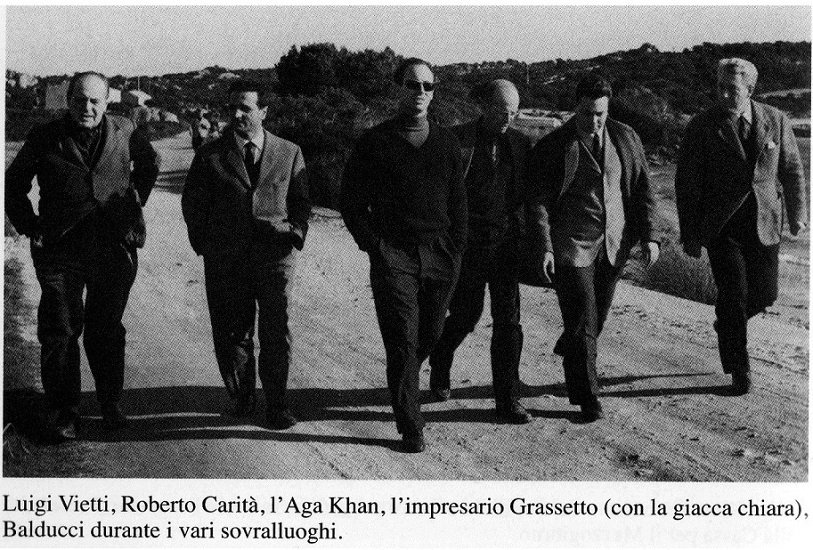

[Luigi Vietti]

[Giancarlo Busiri-Vici]

[Antonio Simon Mossa]

Strict regulations

The hiring process

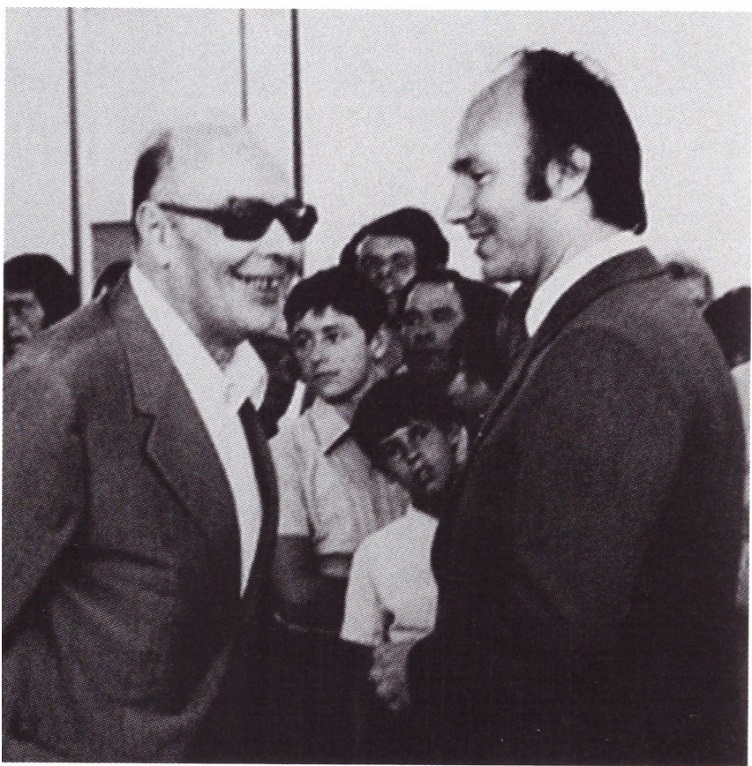

Prime Minister [Pierre] Trudeau

Iva Zanicchi

Alberto Sordi

Adolfo Sarti

President Cossiga

Princess Salima. [A photographer files a lawsuit and takes Aga Khan to court in Tempio Pausania]

The princess on the boat. [The Misadventure of Princess Margaret on a Boat with Her Husband Lord Snowdon and Aga Khan]

Pierino Tizzoni. [Pierino Tizzoni, owner of the Cappuccini and Budelli Islands and founder of Costa Paradiso: the nine “concrete ball” villas by architect Dante Bini on Cappuccini Island]

9. CUBIC CAPACITY – WHAT A CALAMITY! ⇒

The “War of the Plans” •

The Good Mayor. [Giorgino Filigheddu, mayor from 1965 to 1970] •

A visit to the countryside [from the president of the of the Sardinia region Del Rio] •

The Cala Razza di Juncu project [without success, with the municipality of Olbia] •

10. OTHER PROJECTS, OTHER PROBLEMS ⇒

Double standards. [The Italia Nostra Association and newspapers such as Corriere della Sera, under Giulia Maria Crespi, L’Espresso, and others target Costa Smeralda •

The casino at Porto Cervo, [The Hotel at Pevero, the Villa at Spiaggia del Principe: The Aga Khan Gives Them Up] •

11. THE HISTORY OF THE MASTER PLAN ⇒

The city planning law •

Awaiting a signature. [With the new urban planning assessor, the communist Muledda, they are on the verge of signing] •

«Not a single meter less». [The Aga Khan rejects the agreement that, for Riccardi, was instead a long-awaited achievement] •

“Italia nostra” to the attack [and Complaints by the Costa Smeralda Consortium against the architect Cederna, the president of Italia Nostra Giussani, the director of “Corriere della Sera” Spadolini and the journalist Giorgio Bocca] •

A chimney between two rocks [and the lawsuit threatened by Giulia Maria Crespi, the majority shareholder of Corriere della Sera] •

13. NEITHER WITH YOU NOR WITHOUT YOU ⇒

That time in Saint Moritz [- February 1982] •

A bottle of Verve Cliquot. [The Serious Dispute Between the Aga Khan and Lawyer Paolo Riccardi, Who Resigns] •

«Je suis bouleversé». [Ardoin tells Riccardi that he is “shocked”] •

14. THE END AFTER THE END

The negotiations

A few errors on the Coast

APPENDIX

The kidnapping season: memories of Judge Lombardini

Chronology of events

A Little Prehistory

Presentation di Laurence Camillo

The ancient territory which would eventually become the Costa Smeralda was virtually uninhabited up until two centuries ago. The part which goes from Piccolo Pevero to Liscia di Vacca and Poltu Quatu was difficult to reach by land, surrounded as it was by steep mountains, covered with an impenetrable forest and impregnable rocks. And, naturally, without any roads. However, it was an enchanted valley, rich with game and fishing, with a splendid coast and jagged cliffs looking out on limpid turquoise waters. During antiquity, at Arzachena instead, there was a significant presence of people, in a tiny village some 15 kilometres inland, some of whom most likely occasionally ventured out to the coast.

Sardinians generally feared the sea, above all during medieval times, when pirates, who had always threatened this land, multiplied their raids. Monte Moro, which towers over Porto Cervo, takes its name from its function as look out point against the “Mori”, the dark people. As a result, people settled far from the coast, in the “stazzi,” small country cottages built of granite which blended into their surroundings, but placed in areas invisible from the sea.

The marvelous bay of Porto Cervo remained in its natural state for centuries; not even a fisherman’s cottage interrupted the landscape, for there were no real fishermen in Sardinia. Families of professional fishermen arrived only recently in Gallura, from the island of Ponza, and settled here, like the Avellino family, who made their home at Abbiadori. Occasionally, the inhabitants of the village of Arzachena would go to the coast to hunt or fish, but they found it easier to arrive at Battistoni (today named Baia Sardinia), at Cala di Volpe and Capriccioli, which were more easily accessible.

The first permanent inhabitants of the area were five Corsican Brothers named Orecchioni, arrived in the early nineteenth century. They settled at Liscia di Vacca, where they began a prosperous smuggling operation in salt, sugar, and gunpowder. Their motives for leaving Corsica are unknown, but they were happy in Sardinia and remained there. Memories are still vivid of the incredible noise made when one of the brothers’ considerable deposit of gunpowder hidden in the Conca di Maracca exploded. That same Conca di Maracca, a large cave under the rocks along the curves of the Liscia di Vacca road, served as a hiding place from pirates up until recent times, as recounted by Gavina Orecchioni, the mother of Zio (uncle) Battista.

The inhabitants of Liscia di Vacca slowly increased in number, forming the small hamlet that can be seen today, where they built the first church of the area. They planted wheat at Cala Granu, from whence its name and took their flocks and herds to graze at Liscia di Vacca, “the cow’s meadow”. To reach the mill in Arzachena, they had to go by oxcart, taking a long and bumpy road called a ruccatogghju, opening and closing a series of fifteen gates one by one. Maria Orecchioni went to school in La Maddalena on board a water tanker boat which carried water, loaded at the jetty of the Baia Sardinia, to the inhabitants of La Maddalena.

Tuscan woodsmen arrived as well, to cut down the beautiful woods and slowly burn its logs, in pyres, transforming them into charcoal: traces of their activity can still be seen in the clearings on the slopes of Monte Moro. Sadly, the great oaks and juniper trees of old are almost all gone.

At Abbiadori, the Azara settled and formed another small hamlet of shepherds, who grazed their flocks and herds in the area of Cala di Volpe and even on the islands. “Uncle” Battista Azara used to tell the story of how on his little boat, he used to accompany the dairy cows, which would swim all the way to the island of Mortorio. These inhabitants were not poor; they had a good life and they were happy in their little earthly paradise. They would organize picnics under the trees in various places, which were occasions for young people to meet, to get engaged, and to settle down to raise a family.

Then in the 1950s the first yachts began arriving, such as the famous Croce del Sud of Mentasti, who began purchasing land at Porto Cervo, the Podbielski at Liscia di Vacca, the young Aga Khan at Pevero, Romazzino, Razza di Junco and Cala di Volpe, his half-brother Patrick Guinness at Liscia Ruia and “Punta Guinness,” André Ardoin at Pantogia, Pitrizza, Capo Ferro and elsewhere, Duncan Miller at Capriccioli etc.

A Consortium (Consorzio Costa Smeralda) was founded in the spring of 1961. The “spiritual guide” of the organization was the Aga Khan, who overlooked the whole process attentively, calling upon leading consultants and the most famous architects of the world. He was a real estate developer with a fifty-year investment plan, something unique in Italy and perhaps in the world. Locally, he entrusted the political preparation of the project to a young lawyer from Sassari, Paolo Riccardi, a giant of a man, both in physical stature (6 foot 8) and in diplomatic skills. He was a family and school friend of important men of politics, such as Antonio Segni and Francesco Cossiga, future presidents of the Republic of Italy, and Enrico, Giovanni and Sergio Berlinguer, as well as of many important figures of local regional importance.

During the very first years of the Costa Smeralda, the real estate developers led by the Aga Khan were well regarded by the local authorities and they did not run into bureaucratic obstacles in the realization of their projects, be they hotels, villas or residences. The president of the Region at the time, Efisio Corrias, and the mayors of Arzachena, first Giacomino Tanchis and later Giorgino Filigheddu, were inclined to favor these investments, in which they recognized a new possibility for economic development in an area which was still primarily agricultural. The high regard in which the young Prince Karim was held was so pronounced that in 1966 the municipality of Arzachena bestowed honorary citizenship upon the Aga Khan and whatever construction permits he requested, were immediately granted.

In the latter half of the fifties, instead, a group of “rebels” formed within the Democrazia Cristiana, led by Francesco Cossiga, jokingly nicknamed “The Young Turks.” The group included Pietro Soddu, Paolo Dettori, Nino Giagu de Martini, Piero Are and many others, and one of its adherents was Gian Michele Digosciu of Arzachena. They formed an opposition to Segni and his nephew Nino Costa, upon whose help the group of the Aga Khan had always counted. When he was named provincial secretary for the party, Cossiga took control of the Sassarese DC; that group would dominate the political scene in Sardinia for the next twenty years, over time occupying all of the political appointments available, alternating amongst the regional presidency, the provincial ones, the councilships and the direction of almost all of the bureaucratic apparatus on the island, forming a formidable compact political group.

During that period, the large petrochemical industries also landed on the island, including Nino Rovelli in the north and Angelo Moratti in the south, to take advantage of the huge State financing opportunities designated by the Funds for the South. In this way, industrial mega-plants were born, such as Saras at Sarroch on the gulf of Cagliari, and SIR at Porto Torres.

For their part, the Sardinian politicians looked favorably upon these industrial initiatives, which allowed them to take the backwards countryside out of the Middle Ages and produce a higher quality of life. But there was another reason for their support as well: industrial workers were far more unionized than farmers, and therefore more easily influenced when it came to politics. In other words, they represented a huge block of potential votes, easily swayed.

In short, the group of the “Young Turks,” influenced especially by Soddu, a great believer in the industrialization of Sardinia, preferred to sustain and support large industry rather than the new and still nebulous tourism industry that was was just beginning to appear in Gallura. They therefore began to attack the plans for expansion that the Aga Khan had for the Coast. One of the key battles in this war was the election of Digosciu to the office of mayor of Arzachena.

This mayor found quick support in the regional council when it came to blocking the Aga Khan, and therefore all of the projects presented by the Costa Smeralda were systematically rejected.

To approach the “Young Turks” and manage to convince them of the promise the tourism industry held for the population overall was a protracted job requiring astuteness and patience, which was carried out by Paolo Riccardi. Luckily among the “Young Turks” there were some (Cossiga, Giagu, Are and Soddu) who had been his high school and university classmates in Sassari. With great difficulty, Riccardi eventually managed to convince them and obtain approval for all the allotments and the constructions which we may see completed today on the Costa Smeralda.

Riccardi’s work was, however, interrupted in 1982, upon the severing of relations with the Prince, and he was therefore unable to obtain the approval of the so-called “Master Plan” for the completion of the Costa Smeralda. This part of the plan involved the land stretching from Cala di Volpe to Portisco, and included three new golf courses. Its realisation would have achieved a stable residential community which would have permitted the Costa Smeralda to live all year round, instead of only during the current brief seasonal period.

This defeat contributed to the Aga Khan’s disengagement and then definitive abandonment of the control of the Costa Smeralda Consortium. Exasperated, the prince ceded his role to the American Sheraton company, which was later absorbed by Starwood, which was subsequently taken over by Colony Capital and recently by Qatar Holding. The prince retained “Alisarda” which in the meantime had been renamed “Meridiana,” as well as the Costa Smeralda Yacht Club and a home at Porto Cervo.

The reminiscences of Riccardi give us an indication of his herculean efforts and a glimpse behind the scenes of the negotiations, opening a window on the Sardinian and Italian political situation of those years.

2.

AT THE COURT OF THE AGA KHAN

Plans for tourism. [The Exhibition and Conference in Alghero]

«We have an urgent need». [The Establishment of the Alisarda Company]

[Skill and Connections: A Phone Call to Paris and Consulting on Sardinian Industry and Agriculture]

Liscia Ruja and Rena Bianca. [The Clash with the Ragnedda Brothers]

Plans for tourism. [The Exhibition and Conference in Alghero]

In 1961, with the arrival of the Aga Khan, and with the publicity in national and international newspapers which accompanied his “disembarkation,” the eastern side of Gallura was mobbed by numerous entrepreneurs from all over the world. The race was on to invest in that part of the province of Sassari, which had long been its poorest and most abandoned. All of this occurred amidst the complete indifference of Sardinian politicians.

In Sassari, on the initiative of my close colleague, Raimondo Rizzu, the Municipal government established a Pro Loco (Tourism Office). The same Rizzu was designated its president, and I vice-president. At the meetings with friends, I expressed my conviction of the importance of favoring tourism, in my opinion a one-of-a-kind opportunity for the development of Sardinia. It was the vice-director of the newspaper “La Nuova Sardegna” who gave us the idea of organizing an exposition of tourism plans for the island. All of the tour operators of the moment flocked to it. We also invited the Costa Smeralda Consortium. I had gone to the Consortium office in Olbia and had explained the initiative to Mr. Felix Bigio, who at the time was the Secretary General. His negative response was communicated to me twenty days later. In any case, when the exposition took place, I invited Mr. Bigio to come visit. He participated the following day in the convention that was held at Alghero, at the Hotel Capo Caccia, which was a great success. The Sardinian newspapers gave great importance and thorough coverage both to the conference and the exposition. The exposition, as I have already mentioned, was inaugurated by the Hon. Segni, who had just been elected President of the Republic.

When did the Aga Khan arrive?

The Aga Khan came to Sardinia for the first time in 1961, to see the land that his half-brother Patrick Guinness, had bought the year before. Patrick had come with his boat from Corsica, but his yacht, the famous 16 meter Zaira, had run out of fuel and thus he he had had to stop at Romazzino. On that occasion he met Nicola Azara who, as soon as he had seen the boat, began gesturing to attract the attention of the prince. Azara used the same method to convince Guinness to buy 10 hectares of terrain. Patrick Guinness, once home, spoke to his brother of the purchase and asked him to split the land with him and the Aga Khan accepted. He had paid a ridiculous amount for it, perhaps 3 million lire, a very large figure at the time.

In 1961 the Aga Khan disembarks at Olbia. He rents a boat from the Moro shipyard and arrives for the first time at what at the time was still called Monti di Mola, accompanied by a lawyer named André Ardoin, his business partner and a trusted friend of the prince’s family. They visit the land, and at that point the lawyer Ardoin hits upon an idea: «Say, Prince, why don’t we create another Costa Azzurra on this wonderful land that has such amazing beaches?». And thus the great project begins. They start buying up property, helped in part by John Duncan Miller, who had been one of the first to arrive in Sardinia. Miller was the head of the International Monetary Fund. He had been invited to Sardinia by Giovanni Filigheddu, a manager of the Region of Sardinia who dealt with assistance to underdeveloped areas.

Was he really more handsome than a fairytale prince?

When I met him, in 1962, the Aga Khan was a youth of 25 years. He was terribly handsome, and overflowing with charm and one warmed to him immediately. He was there with his half brother and there was little difference in age between them. Patrick Guinness was blonde, blue-eyed, and refined, but lacked the charisma and friendliness of the Aga Khan. I was immediately impressed by the prince’s communicative skills. He spoke in French at first, but after three or four months he was perfectly fluent in Italian, in addition to English and the other languages that he spoke with his religious followers. Above all I admired his work ethic and his enthusiasm.

«We have an urgent need». [The Establishment of the Alisarda Company]

When did you start working for the Costa Smeralda?

My first meeting was with Mr. Ardoin, a lawyer of the Aga Khan. He came to me for the first time in Sassari and told me, in French: «We have an urgent need.» He needed to finish setting up the company “Alisarda,” an airline that was to offer connections between Olbia and Rome – starting immediately – using the airport of Vena Fiorita, an old “makeshift” dirt runway created by the Germans during the war. It was extremely urgent. They already had a statute; the company had already been formed: in short, everything was ready. All that was missing was to proceed with the certification of the shareholding company and its listing in the business registry. They had turned to Mr. Rinaldi, a Roman lawyer, who had been Under-Secretary during the time of Fascism, whose name had been given to them by “Air France.” Rinaldi had prepared everything: the articles of incorporation, the statute, the board of directors, etc. Mr. Ardoin told me: «We need this certification to be taken care of right now: we have been told that to obtain it from the Court in Rome will take at least three months.»

At the time, the presiding judge at the court of Sassari was Dr. Arcadu, a man with whom I had formed a great friendship, due to the fact that he had married the sister of the Hon. Salvatore Cottoni, Mrs. Speranza. She, in turn, had been sent to me by her brother in order to take legal action against a renter who was not paying part of the rent for a piece of property she owned.

My answer to Ardoin was as follows: «My dear sir, it will indeed take three months, or perhaps two and a half.» I was certain, instead, that I would manage with relative ease in far less time.

I was given all of the documentation necessary, which as a first step needed to be approved of by a notary. The same evening of our meeting, I phoned my own trusted notary, Mr. Toti Maniga, who was also a personal friend: «When will you be in the office tomorrow?» «At nine.» «No, make it eight.» Having explained the necessary steps, I had him prepare the file in order to take it quickly to the Registry office. I handed it personally to the director, the accountant Salvatore Virdis, whom I knew quite well, imploring him to get it registered with the greatest possible urgency. I remember that he said: «Come back in a week.». «No, you’ve got to do it for me today!» He was good enough to grant my request. Right afterward I went to the presiding judge of the court and said to him: «Judge, I need you to do me a huge favor: I need you to finalize the certification of this company. But with the greatest of urgency.» «Summon two judges for me,» he replied. I went to Judge Salvatore Buffoni, another friend of mine, and Judge Vanni Fogu, and told them: «The Presiding Judge wants you in his office for the urgent certification of a corporation.». Within half an hour, the company documents had been approved by the obligatory panel of three judges. All that was missing was the approval of the Attorney General.

I had never had any sort of relationship with him, and therefore I was in no position to ask him for immediate approval. I asked Doctor Arcadu to do me the favor of going to the Attorney General to complete the certification. After an hour, Arcadu gave me back the file so that I could turn it over to the registrar. After two hours, Mr Pinna, the registrar, another friend, handed me a copy of the certification of the “Alisarda” company. Thus I sent a telegram to the lawyer Ardoin saying: “Alisarda” Corporation certified, you may send Mr. Bigio to collect the papers of the Company. This occurred a mere two days after having been assigned the task.

[Skill and Connections: A Phone Call to Paris and Consulting on Sardinian Industry and Agriculture]

At my first meeting with Mr. Ardoin, we dined at the Muroni restaurant, in Piazza d’Italia in Sassari. Mr Ardoin, having finished his lunch, needed to call Paris before leaving. He was worried, because normally it could take as much as two hours to get through to Paris. He asked me if it were possible to call from my house. Obviously I agreed. When we arrive at my home, he says to me: «Who knows how many hours it will take!» And I respond: «Let’s give it a try.» One of my clients was Bua of Ozieri, who was a director at the telephone company, SIP (at the time named TETI). I called him and said: «My dear friend, could you please connect me to this number in Paris?». And he says: «Straight away, Paolo» The connection was instantaneous. Mr. Ardoin couldn’t believe it: «But this is a miracle!» He starts laughing and I explain: «No, it’s just a friend who has facilitated matters.» When he is about to leave, he says to me: «Mr. Riccardi, we would like to ask you one more favor. Would you conduct some research on industries in Sardinia? We have the intention of opening a few. A rather in-depth study.» «Certainly.» I respond.

What I did was extremely simple: among my other responsibilities I was the lawyer for the province of Sassari for Credito Industriale Sardo, so I sent him a study done by the C.I.S., in which the incentives for investors were outlined, including not just industry but hotels as well. The latter was exactly what they were interested in. In my report, I highlighted the fact that fact luxury hotels could not access the special funds made available by free grant. To do so, they had to be budget hotels. Among other things I noted: «They talk about a contribution of 50% of the construction costs, but they have such a low estimated price list that in the end it will only cover 10%: they base calculations on paying 10,000 lire to build one cubic meter, when instead normal building costs are 30,000 lire, so base your calculations on these data.» Subsequently they asked me to do another study on agriculture. And thus began my consulting career for the Aga Khan group.

Liscia Ruja and Rena Bianca. [The Clash with the Ragnedda Brothers]

But when the Mr Ardoin and Mr Bigio spoke with you, did you know who and what they represented?

Who didn’t know? Even the cats knew. Everyone knew, both who they were and what they were not. I did the next consulting job after they had already signed a preliminary sales contract for the acquisition of 500 hectares from the Martini brothers in the area of Liscia Ruja. They had paid 450 million lire. The estate agents were Sebastiano Ragnedda of Arzachena and his brother. Ardoin and Bigio asked me to study the contract: both were very concerned because the Ragnedda were asking for an additional payment of 50 million. In Ardoin’s opinion, that sum was not due, but he was afraid the deal would fall through: «Because you know that Sebastiano, he is a real tough one, and we are afraid that the Martini brothers will end up saying he is right. Mr. Riccardi, what do you think? We cannot lose this land, but these people do not wish to finalize the sale.» I told him: «If you want to, you can give Ragnedda and Martini 50 million more lire, you can do what you wish, but in my opinion it would be completely, and utterly, wrong.»

A few days after the meeting with Ardoin, Bigio invites me to come to Olbia to finalize the sale. His office is a large room on Viale Umberto. In this large room there are scale models of all the land owned by the Consortium and two large desks. He invites me to sit down. «You have a seat and stay there nice and quiet. If I’m not able to convince Ragnedda e Martini that we don’t owe the payment of 50 million, I will call you.» I did not participate in the discussion. When it came to the point about payment, the battle began about the price and the infamous 50 million lire. «Mr. Riccardi, sorry, could you come in for a moment?» Bigio asks me. I introduce myself to the notary, Dr Mario Altea of Tempio, to the two Ragnedda brothers, and to the owners, I’m not sure how many there were, perhaps seven or eight. At the request of Bigio I contest what Sebastiano Ragnedda has said. At that point, the others all start protesting at once. Who the heck is he, what the devil kind of lawyer is he? And I say: «You needn’t worry about who I am or am not. But you may be certain that if you insist on the payment of 50 million extra lire there will be no final deed of sale. At this point, Ragnedda invites the Martinis to leave. I turn to Dr Altea and I invite him to put my declarations on the record. I represent the buyers; there is no deed signed, not for any fault of ours, but for theirs, because they have refused to uphold the conditions of the preliminary contract.

At that point a revolution breaks out: «What have you come here for, who are you, who is this so-called lawyer?» Bastiano Ragnedda goads me, lamenting that they are used to important lawyers, etc etc. The presumptuousness of Ragnedda was legendary. When he had to sell his petrol station in Porto Cervo, “Il Cavallino Bianco (The Little White Horse) to the AGIP company, anyone would have thought that it was he who was the owner of the AGIP colossus and the other man his underling.

In truth, I was young and unknown. But at a certain point, I could sense the agitation of the Martini brothers, who were beginning to see 450 million lire go up in smoke. The more authoritative of the Martinis turns to the notary, who is about to put my declarations down on the record, and asks him for his opinion. The notary Altea, speaking in the Tempiese dialect responds: «What are you waiting for, anyway? The young man is right. Therefore, if you want to close the sale, do so, otherwise I’m ready to record his declaration.».

I wasn’t a child. I was 34 years old. However, I had begun practicing law at 26, meaning that I had relatively limited experience and was little known outside of Sassari. Nonetheless, the deal was made, and no one paid those extra 50 million lire.

3

SEGRETARY GENERAL

The third act. [The Aga Khan and His Brother Patrick Guinness Propose to Paolo Riccardi to Oversee the Costa Smeralda Project]

A wrench thrown into the works. [The “Young Turks,” an Internal Political Faction of the Christian Democracy Party in Sardinia]

From the hill of Porto Cervo. [September 1963: Planning the Village and the First Port]

Honorary citizenship. [The Mayor of Arzachena, Giorgino Filigheddu, Grants Aga Khan Honorary Citizenship]

A man who had time for everything. [Aga Khan: A Tireless Prince]

Mr. Ardoin and the irrepressible prince

The third act. [The Aga Khan and His Brother Patrick Guinness Propose to Paolo Riccardi to Oversee the Costa Smeralda Project]

The third act, we could say, was the consequence of a similar incident. Later the same year, 1962, after two or three months, Bigio calls me and says: «Mr. Riccardi, I have here the Aga Khan and his brother Mr. Guinness, who would like to meet you. There will be a dinner tonight at the Jolly Hotel in Olbia with the harbor master.» Obviously I am happy about the invitation.

After the customary introductions and pleasantries we sit down at the table. The Aga Khan has placed me between him and his half-brother. At the end of the evening, the Aga Khan says: «Mr. Riccardi, we would like very much for you to come and work for us.». I respond: «Prince, I already come to Olbia twice a week for consulting.» Indeed, I had begun serving as consultant to the Costa Smeralda, going to Olbia two afternoons a week. To get there, I had to drive for quite a long stretch on dirt roads and pass through Ozieri, a two-and-a-half hour drive. Naturally, Bigio, a careful administrator, did not trust me entirely, just as he did not trust anyone. Thus he would pass me only one file at a time, to the point that I was becoming bored. One day I informed him: «Look, Mr Bigio, I am leaving now for Sassari. You do not know me well, Sir. I work fast, and understand things so quickly that you need to prepare at least 50 files for me to examine together. I won’t return except under these conditions, because I just haven’t got time to waste. In the end, Bigio loaded me up with so many problems that I was losing my mind.

At the end of dinner, before leaving, the Aga Khan invites me to come by his office the following morning at eight. At the meeting, in addition to the Aga Khan, also present were Bigio, Ardoin and Patrick Guinness. The Aga Khan is the first to speak: «We would like for you to come work for us on a steady basis. Tell us what salary you require.» I respond: «I have my own firm. I have commitments, I can come three times a week.» The Aga Khan answers: «No, no, we want a greater commitment from you.»

Ultimately, we came to an agreement and I began working for them three to four days a week. But after less than a month, there was so much work to be done that I had to give up the firm in Sassari. In the meantime, the Aga Khan had named me president of all of his companies and had invited me to participate as partner in several others, naturally as a figurehead. For “Alisarda” there was a law that foreign funds could not make up more than a third of the capital possessed by Italian airlines: thus he was assessed 20% of the shares, and he had me subscribe to 80% of the shares, without our having made reciprocal declarations on their real value. To say the least, there was a very strong, constant relationship of trust between us, which lasted until the moment of my resignation in 1982.

In May 1963 they named me Secretary General of the Costa Smeralda Consortium. I wasn’t named president only of the “Cerasarda” company, one of many belonging to the Aga Khan, because before having met me, he had named Lellè Devilla the lawyer from Sassari as president, at the suggestion of the Hon. Nino Costa, who had been introduced to the Aga Khan by the Hon. Segni, before the professor was made President of the Republic.

The Aga Khan had met Hon. Segni at the airport of Alghero and the professor had promised to help him whenever needed. Segni realized that the projects of the young prince represented a great advantage for Sardinia, and therefore had told him: «Whatever you need, contact my nephew, the Hon. Costa». Nino Costa had been president of the Federconsorzi, who was a right-wing politician, very intelligent, a good man, athletic, who bred horses and had a large horse farm at Crucca, in the Nurra di Sassari. At the time he was the treasurer of the Region of Sardinia. He was the cousin of the wife of Segni, an extraordinary person, a great lady, from one of the most important families in Sassari.

A wrench thrown into the works. [The “Young Turks,” an Internal Political Faction of the Christian Democracy Party in Sardinia]

At the beginning, the Aga Khan turned to Hon. Costa, neglecting to make contact with the famous so-called “Young Turks”whose leader was Francesco Cossiga, together with Pietro Soddu, Pietro Pala, Paolo Dettori and Nino Giagu De Martini as well as others. In 1956, they had unexpectedly won the provincial party congress of the Democrazia Cristiana (Christian Democrats) and they had managed to take the reins of command. Cossiga had become Provincial secretary for the DC and a few years later, at the very young age of 29, a member of the Italian parliament. After a few years, he was given his first office as Under Secretary of the Air force to the Ministry of Defense. The “Young Turks” belonged to the left wing of the DC, and were in opposition to Costa, who was on the right. Naturally, this had resulted in the “Young Turks” seeing the Aga Khan, his initiatives, and above all his relationship with the Hon. Costa in an unfavorable light; in truth, they did not believe in tourism, and had in fact concentrated all of their energies in favoring the birth of heavy industries, such as the petrol-chemical industry of Mr. Rovelli in Porto Torres in the province of Sassari, and the Saras company of Angelo Moratti in Sarroch, near Cagliari. This posed many problems for us and I had to use all of my influence in obtaining a more favorable political attitude towards our development.

From the hill of Porto Cervo. [September 1963: Planning the Village and the First Port]

At the beginning, it was only possible to get to Porto Cervo by jeep, by way of the same rough dirt road used by the locals “montimolesi” to take their ox carts from Liscia di Vacca to Arzachena. I remember that one September day in 1963, I arrived with the Aga Khan, Ardoin and a group of architects on top of the hill of Porto Cervo, where the house of Prince Amin would later be built. There, seated on the rocks, the Aga Khan began to describe his project to us. He told how the piers of the quay would be built, already fixing the date of the inauguration of the port for 14 August 1964. I thought «This fellow is out of his mind…» There was no electricity. There was no water. «He is a visionary!» I started to become concerned: «This is a young hothead! Miracles may well be possible, but even with a miracle it can’t be carried out by that date.»

At that point, I made one of the dumbest moves of my life. Because the Aga Khan said: «So, choose a place for your home at Porto Cervo.» Mr. Ardoin, the lawyer, and Mr. Vietti, the architect, chose Porto Cervo Nord, while the architect Mr Busiri-Vici chose central Porto Cervo. And the Aga Khan: «Mr. Riccardi, and you?» «No, thank you, I have bought another piece of land already.» I was thinking of the price he would be asking, «God knows what a con this will be!» And so like a fool I turned down the biggest gift I have ever been offered.

The miracle did in fact take place, because right on time, on 14 August 1964, the East port of Porto Cervo was inaugurated, now known as “Porto Vecchio”, the “Old Port”.

The prince was tireless when it came to planning out loud: «Mr. Riccardi, please, do take notes, for this problem and for this other one…». I would pretend to take them. After two or three meetings, he realized that I wasn’t taking any notes at all. Later, as soon as he would arrive in Paris or Geneva – at the time his headquarters was in a splendid villa in Merimont, in Geneva, with an estate of 18 hectares near the Hotel Intercontinental – he would send me a telex: «Mr. Riccardi, please remember… » «Mr. Riccardi, don’t forget… » «Mr. Riccardi, had you thought of this…?», «Mr. Riccardi, did you … » It was never-ending. «You need to…», «Did you remember…?», «Do let me know…», «Do keep me informed…».

And I would be there dictating everything that we did during the day to my secretary, also because he would call me back to see what I had done. When he came, he would work from 6 am. to midnight. Once he held me until the 31st of December because there was an urgent matter to resolve. My family had gone to San Martino di Castrozza in the Alps for Christmas: I was to join them for New Year’s Eve, and I got there in the middle of the night, after a perilous taxi ride in the middle of a blizzard.

Honorary Citizenship. [The Mayor of Arzachena, Giorgino Filigheddu, Grants Aga Khan Honorary Citizenship]

One day in 1996 the Aga Khan complained to me: «Just look at these people from Olbia: when I paid a courtesy visit to the mayor and the city council, they promised me honorary citizenship, but they never gave it to me.» With this fact in mind, I go to the mayor of Arzachena, Giorgino Filigheddu, and say: «My dear mayor, would you like to tell the city council that the Aga Khan himself is going to pay you a visit, not just this scamorza cheese Riccardi? If you care, do you authorize me to tell the Aga Khan that you intend to give him honorary citizenship in Arzachena?»

I inform the Aga Khan: «Look, Prince, the mayor summoned me to give me a piece of good news. It is quite extraordinary: it seems that he, his cabinet and the city council wish to grant you honorary citizenship of Arzachena». The date is set and he accepts the invitation with great enthusiasm: «Please write me a speech to give on the occasion.» I must have written, reread, and rewritten that speech ten times. I would correct part of it, but it wouldn’t be right. Then another part, and another. Finally, we managed to come to an agreement. Before leaving, the prince reread it and tucked it into his pocket.

After the honors ceremony, which took place on a stage in the main square erected for that very purpose, the Aga Khan, turning to the crowd filling every corner of the square, ignored the prepared speech and talked off the cuff for at least half an hour. He explained the programs of the Costa Smeralda to the crowd, and it turned into a wonderful local celebration. He spoke in impeccable Italian and his speech was interrupted by applause at least ten times. From that moment on, the mayor and all his administration staff, satisfied by the fact that the Aga Khan had finally come to visit Arzachena, changed their attitude towards us.

The Mayor, Giorgino Filigheddu, advised me: «Look, Mr. Riccardi. Do what you want on the Costa Smeralda, just as long as you avoid conflicts with Arzachena: if you get into a dispute with Arzachena, it’s all over.» After that, we went forward without any problems. We were able to obtain licenses to build apartments and offices in Porto Cervo, which was the first phase.

Had the buildings at Cala di Volpe and Pitrizza already been built? And who gave you the permits?

Yes. I hadn’t been engaged yet. It would definitely have been the administration of Mayor Giacometti Tanchis. I think that the contacts were maintained by Mr Bigio until my arrival in 1962. Then, from May 1963 to 1965, I was the one who took care of maintaining contact with Tanchis. Our relationship with him and his administration was always friendly, and our collaboration fruitful: he was a kind, simple person, who showed a great admiration for our projects and saw in the Aga Khan a hard worker who in a short time had, with his initiatives, changed the life of the whole community. Giorgino Filigheddu was elected Mayor in 1965 and remained in office until August 1969. He also helped us a great deal.

A man who had time for everything. [Aga Khan: A Tireless Prince]

Keeping up with the Aga Khan was truly exhausting, but intriguing as well: he had me completely involved in his great project. The entire road which led from Arzachena to Abbiadori was unpaved. To asphalt it, the Province had held a competition won by the surveyors Gavino Soro, Lelle Rais and Rosas, friends of mine: the road was finished before expected. I was on excellent terms with the Guerri enterprise, but every day I still had to give the Aga Khan a report on how many kilometers they had paved, as he was afraid that the road would not be ready for the inauguration date of the port.

To get to Abbiadori, Porto Cervo and Cala di Volpe there was a sheep track through the countryside. There too, absolute disaster. The prince: «Mr. Riccardi, we must do this, we need to do that…», a stream of telexes, to which I had to respond, again by telex. It was truly a constant daily fatigue, but very stimulating as well, because I could see that my “padrone” – yes, “padrone”, the boss, as for me that is how it felt, with me the slave taking orders – was exceptionally foresighted, well-prepared, and concrete in his dealings.

Karim Aga Khan, the forty-ninth Imam of the Ismailites, at only 26 years old, was a very mature man. His grandfather had wanted Prince Karim to succeed him at the age of only 18, with a flock of 30 million adoring followers. Every fortnight he would summon the most important of his faithful to Geneva, to the Hotel Intercontinental, a meeting of no fewer than 300 people.

And you, Mr. Riccardi, did you feel intimidated by the Aga Khan?

I would definitely say no. When we lunched with the authorities, a horseshoe-shaped table would be prepared. I would always sit to the side, in a corner. In general, I would sit with friends, local and regional council members and MPs, fun people, and we were always exchanging wisecracks and jokes and laughing. And he, the prince, would comment: «What are you talking about that has you laughing so?» And I would respond: «Nothing appropriate for you.» I would turn around and he would start laughing. He was really very friendly and fun. All this to say that no, I never felt intimidated by him. Respect is something different.

Mr. Ardoin and the irrepressible prince

Many managers would arrive at the meetings full of fear: «What’s he like? Is he in a good mood?» They feared him because he was truly strict and examined things in depth. In truth, a lot of time could end up wasted in these meetings because, picky as he was, he would discuss even the most minute detail. I did not want to sit there trapped, following the many tiny problems of the various managers. Finally one day I said: «Prince, when you come to the Coast, numerous people come to me asking to meet you. I receive them and come up with several excuses for you to avoid meeting them, given that they just want to meet you and they would only make you waste precious time. This is why I cannot stay in meetings with you all day long. You needn’t worry. If you have a problem, you can just call me and we will work it out.»

On that same occasion, I suggested that whenever he came to the Coast, he allow me to set up a meeting together with Mr. Ardoin, with a precise order of business including all of the matters which in my judgment ought to be discussed, of which I would advise them both in advance. At the beginning he seemed a bit irritated, but we followed this system regularly for many years. If in drawing up the order of the day I ever forgot a topic, he would send me a telex adding those that he wished to discuss. Those meetings started at 8 in the morning at the latest and would run as late as 10 at night. For lunch, the Aga Khan would order sandwiches, water and cappuccino from the Hotel Cervo. One day, dead tired, I slipped out and went home for a nap. When I came back, perhaps an hour later, the Aga Khan asked me: «Did you sleep well, Mr. Riccardi?» And I: «Not at all, prince, because in general I sleep as much as an hour and a half after lunch.» He chuckled, and from that day on, he never sought me out right after lunch, knowing that I would slip home to take a little nap.

4

LEARNING TO FLY

[FROM ALISARDA TO MERIDIANA]

The “Alisarda”

«You see, Romiti»

Landing with the sheep

At war with the Ministry. [Giuseppe Sitaiolo]

To the Public Prosecutor. [Giuseppe Sitaiolo]

A friend in the government. [Salvatore Cottoni; Alisarda Faces Opposition from Alitalia]

It was called Venafiorita. [The Olbia-Costa Smeralda Airport is Established]

Nordio comes to the rescue. [The Request to the Alitalia President for the Cagliari-Milan Route: Problems and Clashes]

We’ll even talk to the communists

Looking for other routes. [Alisarda Expands]

A photo on horseback. [Kenya and Tanzania Sell the First Planes to Alisarda: Sir Pirbai, the Mediator of the Deal with Kenya; Adjabali Kassan, the Only Ismaili Allowed at the Aga Khan’s Court in Costa Smeralda]

The party membership card. [Paolo Riccardi Joins the Communist Party: A Membership Card to Use at the Right Moment]

The “Alisarda”

Mr. Riccardi, we never did finish our discussion of the “Alisarda.”

This is where Count Ranchella, president of “Alisarda,” comes on the scene, along with his peers charged with resolving the problems of the company, so that literally it would be possible to start flying. Nice fellow, that Count Ranchella. The classic example of a Roman who had received his title of Count from the Vatican. The other member of the board of directors of “Alisarda” was a general, the only very good, capable person, of whom I no longer remember the name. But generally the meetings of the board were a horrifying mish-mash of bickering and squabbling.

I would attend these meetings together with Mr. Ardoin and Mr. Bigio. We would almost always meet in Rome, occasionally in Olbia. The carping of this count lasted two or three years, until we finally managed to change the board of directors, using my presidency to put an end to the shouting of the Vatican Count.

I remember that one time, as part of his compensation, he asked us for a photograph of the Aga Khan with a special dedication, and insisted upon meeting the Aga Khan in person. The meeting took place at the Hotel Excelsior. When he arrived punctually for the appointment, the arrival of Conte Ranchella was announced by the reception by telephone. I tell Mr Ardoin: «I’ll have him come up with me.» As soon as he sees me, the Count starts: «I’m going to make a fuss, I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that…» When we come up to Mr. Ardoin, always a man with a ready wit, he deftly forestalls this tirade with a burst of friendly chatter: «Well, Count, how is the grape harvest going? I mean the sale of the wine. And the barrels?» (The conte possessed a property and sold wine.)

This incipit stunned him. He didn’t say another word, except with regard to issues concerning “Alisarda”.

And the photograph of the Aga Khan with that dedication?

The Aga Khan never sent it to him. Ranchella was a nightmare for many years.

«You see, Romiti»

Once I became president, I started to liaison with the authorities. My first meetings were with the Hon. Salvatore Mannironi, at the time the Under Secretary for Transport. And the first battle began. “Alitalia” did not see the Aga Khan in a positive light, as his new airline was potentially a fearsome competitor. “Alitalia” ruled over everyone else. I still remember the first letter written by the director of the Ministry of Transport in response to our request for the concession of a route, the Cagliari-Olbia-Rome, for two planes bought specifically for that purpose, both small Beechcraft. The letter from the Ministry of Transport had inadvertently been sent to us with a note written in pencil by Mr. Romiti, who was the CEO of “Alitalia”: «You may send it to “Alisarda,” now it’s OK.»

To illustrate just what kind of connection there was between “Alitalia” and Civilavia, the Civil Aviation authority, I showed this letter to the Hon. Mannironi. Obedient poodle that he was, he looked at me without saying a word. Mute, he refused to comment. Laughing, I said to him: «See what you can do, OK?» I am sure that it was his intervention which led to a meeting in Porto Cervo between Romiti and the general manager of Civilavia. After that meeting, the relations both with Civilavia and with “Alitalia” were marked by a greater attention to our problems.

Landing with the sheep

When did Alisarda start flying?

The inauguration of the first paid flight of the airline (the ticket in 1964 cost 5 thousand lire) took place on the Rome-Olbia route. I, Bigio and a couple of Americans were the first passengers. At the moment of landing, the American woman started screaming like banshees: the plane was making its descent on a dirt runway, right in the middle of which was a flock of sheep being chased by the shepherd who was trying to shoo them away. And Bigio, the whole time, trying to explain in English that that was the airport.

Back then, guests were welcomed at a small tent where two men were working, one of the first employees, Izzo the captain and his assistant. Soon there were four staff. The story I just told was the first flight of the two famous Beechcraft. What was never told instead is that one of the two Beechcraft, as it was about to land at Rome Ciampino, half fell apart: that news never appeared in the press, for it would have spelled the end of “Alisarda.” The Aga Khan rightly said: «Before we start, I want to check everything.» One of those two planes is still there, abandoned at the Rome airport.

Following the two “small” Beechcraft, two 18-seater North Aviation Beechcraft were acquired. This purchase occurred after several meetings with the Ministry, always with the assistance of the Hon. Mannironi, who allowed us to take over the rights to operate on the Olbia-Rome route, which had never before been used, from their owner ATI airline. We then moved up to two Fokker F27s.

At war with the Ministry. [Giuseppe Sitaiolo]

And what was your role with “Alisarda”?

I had far too many commitments at that time. It had become impossible to liaise with all of our political and administrative contacts. I therefore decided to have myself substituted as president of “Alisarda.” I gave the Aga Khan and Mr Ardoin the name of a Sardinian who had been recommended to me by Mr Pellegrini, the lawyer for the CIS, Credito Industriale Sardo. Raffaele Garzia, the president of CIS, consulted with me and seconded the positive opinions I had gathered on Mr Efisio Carta of Oristano, well known and well regarded by Sardinian politicians, capable of maintaining relations at a high level. After serving as president for two years Carta resigned and the Aga Khan had me take the reins once again at “Alisarda,” which I did for another 15 years, until 1982.

One of my first tasks, after reassuming the office of president, was to verify for myself the current status of our applications regarding the transfer to us of flights to Sardinia which had previously been granted to ATI. I had been warned of the overbearing and arrogant nature of a manager for that sector by the name of Giuseppe Sitaiolo, who was in charge of services for Civilavia; it was said that he wouldn’t listen to anyone. But we survived all the same

My main source for this information was Mr. La Manna, an accountant who was one of our employees, tasked with acting as liaison to the Ministries. One day he complained: «Mr. Riccardi, Sitaiolo is an impossible person. Just think, my wife, who works there at the Ministry in his same department took the liberty of attending a meeting of the CISL (a workers’ union) and he ostracized her. You really have to tread gently with him. I had already had other encounters with the executives of the Ministries, who ultimately take advantage of the fact that the ministries last a year at most, while they themselves remain. For this reason, it’s very important to have good relations with Ministry executives even if doing so is often very difficult. «We will just have to bear with Mr Sitaiolo.»

I ask for an appointment on a certain day, which is set for nine am. Having become familiar through other circumstances with the behavior of some government executives, I arrive at the appointment with Mr Sitaiolo prepared with books on horse racing, as well as three or four newspapers, knowing that I am going to be made to wait at least three hours. And so it is. Nine, nine-thirty, ten. At ten, an usher comes into the room where I am waiting, and asks: «Do you need anything?» «No, thank you, I don’t need anything, except perhaps a toilet before very long,» I laugh, and continue reading. At a quarter to noon, the secretary arrives. She is perhaps even haughtier, albeit very lovely. Before she can say a thing, I take the words out of her mouth: «Dr Sitaiolo has been summoned by the Minister?» Ill at ease, she confirms my hypothesis.«Please ask Dr. Sitaiolo, who is on his way out, if he can meet me at nine tomorrow.» She quickly returns, very embarrassed: «Yes, he can receive you at nine.» «Miss,» I ask her as she is leaving, «could you kindly tell me what time it is?» She responds: «It is five to noon» «Just as my watch says. Until tomorrow at nine, then.»

To the Public Prosecutor. [Giuseppe Sitaiolo]

I leave. I go to the office of “Alisarda” and I sit down at the typewriter. I begin: «To the Public Prosecutor of the Court in Rome. I, Paolo Riccardi, born in Sassari…, President of the “Alisarda” company, am writing to report the following: The “Alisarda” company, some time ago, applied for the concession of the Olbia-Rome-Olbia and Genoa-Olbia-Cagliari routes, but Dr Sitaiolo, who is in charge of this service, has not even taken the trouble to call a meeting of the commission which examines these applications, despite the fact that over three years have passed since our request. It is my opinion that he is committing a crime, that of dereliction of duty, and herewith I would like to set out in detail to your Honor exactly what damages the “Alisarda” company has suffered as a result of these delays…».

The following morning, I bring a copy of the letter with me to the appointment with Dr. Sitaiolo. Nine o’clock sharp. Five past nine, a quarter past. I knock on the door of the secretary’s office and say: «Excuse me, would you mind giving this file to Dr. Sitaiolo? You may tell him that I can see him at exactly twelve noon tomorrow at the offices of “Alisarda.” I cannot wait even five minutes more today as I have to deposit in this exposé to the Rome Public Prosecutor’s office.» Without saying any more, I say goodbye and leave. Then I awaited a reaction. I told myself: «There is bound to be a reaction of one kind or another.» After six or seven hours, I receive a phone call from a dear friend, Dr. Peppino Leonardi, who had been head of the administrative office for the Hon. Cottoni when Cottoni was Under Secretary for Public Works and later Transport. «What on earth are you up to? Sitaiolo is a dear friend, what do you think you’re doing?» I respond: «Peppino, he cannot behave this way. Come with him, if he is willing, to my office, but I’m not backing down. If he comes, fine, if not, I’m ready to turn in my exposé..» «Don’t do it, dammit!» «Peppino, I will.»