INDEX

Introduction

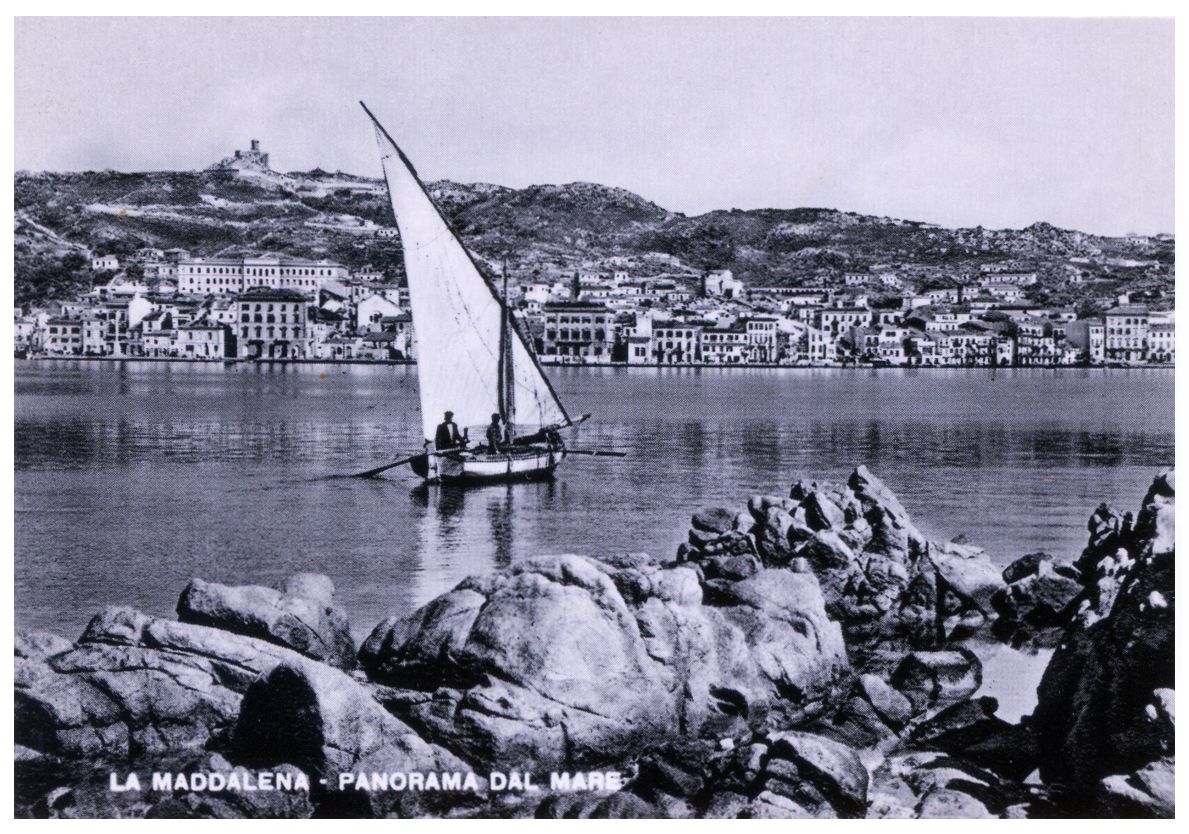

I. The Voyage and Arrival at Maddalena

II. Caprera and its Cincinnatus

III. A Day in Maddalena

IV. Departure. A caprice before departing [: Sardinia and Palau]

Note. Correct words: Ballestreri, Calavela, Parau

Introduction

Among the artists who graced Rome with their presence during the winter of 1849 – that winter so prolific of political hopes and vicissitudes – there came one, whose extraordinary performance on the mandolin excited the greatest astonishment and delight. His name was Vimercati, an affable old man, whose courteous manners drew forth as much friendly sympathy as his beautiful music inspired admiration.

Myself initiated in the difficulties of the mandolin, I was, perhaps more than others of his audiences, enraptured with the marvellous tones which he brought out of his instrument. I sought his acquaintance, and he soon became one of my most assiduous visitors.

One evening, as I was surrounded by a little circle of friends, my virtuoso so completely surpassed himself, that I could not help asking him what could possibly have induced him to devote his incomparable talent to so ungrateful an instrument?

His reply was charmingly naïve. “Madam,” said he, “it was precisely because all other artists seemed to despise the poor mandolin that I declared myself its champion, and determined to rescue it from what has so long been its fate, the accompaniment of the vulgar songs of the common people”.

“My dear reader, I hope, will not think that I have the presumption to compare the feeble powers of my pen with the musical genius of the master of whom I have spoken; but, in calling public attention to the insignificant island of Maddalena, a rock that has been almost forgotten since the time of the Romans, I fancy I hear a murmur of surprise, to which, adopting the idea of my friend Vimercati, I would answer “It, is precisely because it is so neglected and forgotten, and that it is the only one of the Mediterranean Isles that has not found an explorer and describer, that I have determined to make its beauties and attractions my theme.”

Corsica, enveloped in the magic veil of its historical past, has become well known to us by the recent work of Gregorovius. Sardinia can boast the classic pages of La Marmora. Elba has been described by M. Valery. Sicily by Parthei, Mrs. Power, and others. Capraja, Ischia, Procida, Capri, Stromboli, and Palmaria, have all had their painters and their poets too – but who has ever dreamed of writing upon Maddalena, though she may also vaunt herself of her historical recollections? Was she not the Phintonis of the Greeks and Latins? The ruined forts which crown her heights, and whose crumbling walls mingle their grey tints with the masses of granite from which they spring, are still existing witnesses Garibaldi at Home of their importance as a place of refuge, where the population ensconced themselves against the invasion of Turks and pirates; and is not the name of “Nelson an household word in “the mouths of the islanders, who all know that their peaceful Archipelago was once the rendez-vous of the fleet of the British hero, and that there floated the flag which was so gloriously honoured at Trafalgar by his triumph and his death!

Even at this present moment she is the chosen retirement of an aged man of noble heart and mind, who was the friend of Byron and Shelley, and who has gone thither to seek for health, in an air so pure and an atmosphere so revivifying.

And is it not to the shores of her sister island “Caprera,” that the Cincinnatus of our times has withdrawn himself from the world and its delusive hopes, until the day shall dawn on his distracted country, when her people may be found worthy of freedom and capable of attaining it, and he shall be recalled from his plough by the messenger of such glad tidings? (This was written in 1858).

Why is it that Maddalena, whose climate. and position offer so many advantages, has never attracted the attention of those wealthy English gentlemen whose beautiful yachts glide “o’er the glad waters of the dark blue sea?” Why is it that the languishing invalid, the misanthrope who has been sated with everything, and the philosopher who is everything to himself, does not come here for health, or for that isolation so congenial both to the strong mind and to the wounded heart? Where can the pallid victim of disease find more examples of health and longevity? Where will the sportsman meet such abundance of game, or the angler hope for better exercise of his art, than in this secluded spot, where the mountains are so picturesque and the blue waters so transparent?

May my present description of this islet prove an attraction to some few travellers, or some few invalids, whose presence there may help to decrease the poverty of its inhabitants, extend their little commerce, and make their intercourse with the Continent more frequent! If I should be the means of obtaining for her such advantages as these, my end will be attained and my labour rewarded.

CHAPTER I.

La Maddalena

AND this terrible weather, Madame, does it not frighten you from your projected journey?” was the friendly greeting of Captain D. as, dripping wet from a heavy thunder shower he entered my sitting-room, at no time very light, but now, on a stormy October morning, when the lightning was playing about, and the sluices of heaven seemed to have been opened on the city of Genoa, was so dark that I could scarcely recognize my visitor. I was sitting ready for my departure, and at once replied, “If the sea be not too rough for you, Captain, I shall not release you from your engagement.

“Madame,” he answered, with a sarcastic smile, “would you compare your courage with that of an old sailor, who has braved danger all his life, and grown grey in the midst of tempests?”

Certainly not. I never dreamed of such a comparison; but it occurred to me that the father of a family would have a fair excuse for avoiding needless risk.”

“It must be allowed, Madame, that we could hardly have been more unfortunate in our weather. The barometer has been falling since yesterday, and, moreover, instead of a passage in the fast-sailing St. George,’ we shall be tossed about, I know not how long, in the old ‘Virgilio,’ which backs against the waves. But they say, ‘what woman wills, God wills;’ and since you are determined to go, let us not delay.

“I took the arm of my companion, and we left the “Hotel della Vittoria” together.

* * * *

The aspect of that noisy, bustling part of the city, which extends from the Piazza dell’Annunciata to the bridge, was so changed during this heavy storm, that it was scarcely to be recognized. The eye met neither the young Genoises, gracefully fluttering their fans, nor the matrons enveloped in their variously coloured “mezzara.” The ear was not pierced by the shrill cries of the vendors of the “Movimento,” (A newspaper so called), and the multitude of other brochures in public demand.

The thunderstorm had sent every one to shelter but that row of women so perseveringly offering their smoking chesnuts for sale. Along the streaming pavement, far or near, nothing was to be seen but one of those files of mules so often traversing the streets of Genoa, heavily laden, but holding their heads high, and shaking their tinkling bells. The “Portico Nuovo” gave us but a momentary cover from the wind and the torrents of rain, but we soon reached the quay, where we were glad to avail ourselves of one of the common boats.

The “Virgilio” was already getting up steam. Although she lay but a short way off, it was not without difficulty that we threaded our way through the multitude of boats which surrounded her. Scarcely had I placed my foot on board, and cast one hurried glance around me, when I could have fancied myself no longer in Europe, but transported to the northern coast of Africa, or to some gulf in the Grecian Archipelago. Never had I witnessed a parallel confusion, never heard sounds more deafening.

I soon discovered that my companion and I were the sole occupants of the chief cabins. In those of the second class there were no passengers at all. In the third, but few. The fourth, however, swarmed with people. This throng was chiefly composed of poor women in tattered clothes, suckling their infants, and closely followed by children of every age, some of them crying, and some consoling themselves with green fruit. Quantities of boxes and cases, sacks of chesnuts, and baskets full of pâtes de gène, were heaped pell-mell upon the deck, while a mass of spades and pickaxes, and carpenter’s tools, completed its multifarious encumbrances.

Already overcome by the weather, I felt quite discouraged in the midst of such a chaos of miserable objects, whose appearance showed plainly how wild and uncultivated must be the people of the island I was about to visit. I do not know if my impressions are like those of others, but upon me the aspect of the sky has so much influence, that a project conceived in a bright sunshine becomes an absolute folly when realized in the midst of cold and rain. I could not help thinking of the “Semillante,” the “Castor,” and other vessels, much superior to ours, which had nevertheless been lost in the waters we were now to navigate. My disposition to hypochondria went so far as to entail on me a species of remorse at the thought that I was dragging the father of a family into an enterprise which was beginning under such sinister auspices. However, “Alea jacta erat.”

The side ladder of the vessel was hauled up, the hatches were closed, the paddle-wheels began to revolve, and in a few minutes the heavily laden “Virgilio” was in the open sea.

I endeavoured to drive away all my sad thoughts, and, in response to a bell which then sounded, I allowed my companion to conduct me into the saloon where breakfast awaited us, and where we found the captain of the vessel, and a Sardinian naval officer charged with the military surveillance of the ship. The destination of the packets on this line is “Porto Torres,” the port of Sassari; and it is only once a month that they touch at La Maddalena, in order to land passengers there, some of whom are going to neighbouring islands, and others to the coast of Sardinia.

Our two fellow occupants of the saloon expressed much surprise on hearing that, instead of Porto Torres, I was going to the small island of La Maddalena. It roused their curiosity; and though Captain D-related several of his adventures in the Crimea, he could not withdraw their attention from the strangeness of my plan. But I soon found it impossible to take further part either in the conversation or in the repast, for the terrible disorder which no remedy will cure, and against which the efforts of science are powerless, began to seize me so violently, that there was nothing left for me but a sudden retreat from the table. Captain D’s strong arm was scarcely sufficient to support me across the deck, now rocked by the swell. Those who have never witnessed such scenes can form but little idea of them from description. The most exacting of readers would willingly excuse me from the details of all that now met my eye. Let me therefore drop a veil over the picture! During sixteen long hours of unequal struggle, the “Virgilio” had to bear up against the heavy waves of a raging sea.

During sixteen long hours was, I plunged in that deplorable state, which makes us sensible of all the misery of our nature. At last Captain D entered my cabin with the welcome intelligence that the worst part of the voyage was over, and that, having reached the Cape of Corsica, we should be sheltered by its mountainous coast.

The promise of so experienced a sailor was realized as quickly as if he had pronounced some magic charm. Everything became calm, as if by enchantment; and after a very tolerable night, I was agreeably surprised in the morning by a bright ray of sun, which presaged a fine day. I dressed myself hastily and went on deck. All my fears vanished, now that my sufferings were over, and that I inhaled the cool air of this radiant morning, and saw the azure-tint of a cloudless heaven reflected in the transparent water below.

All the passengers appeared to enjoy, as I did, this magnificent spectacle, and every face expanded with pleasure at the prospect of a happy and early debarkation. To the east the sea extended without any visible limit, effacing the last faint lines of the Italian coast. To the west we discerned the steep mountains of Corsica, rising in sublime majesty. The declivities which descended towards the shore were covered with a rich and verdant growth, contrasting wonderfully with the masses of granite which formed the foundation of the picture-masses whose jagged tops were partially concealed by fantastically shaped clouds.

It was thus that Corsica first rose to my sight in all its grandeur, displaying its beauties to my eye, and bringing all its glorious recollections to my mind.

The sight was most imposing, and thanks to a good telescope, I was enabled to take in all the picturesque details of the coast, along which we passed at a distance of two or three miles. The ground was covered with wood, and plantations of vines and olives succeeding each other without end, and forming on the whole an admirable panorama. At one point the attention was arrested by a chapel, dedicated, perhaps, to the Virgin; at another by a castle of the middle ages. Here some picturesque ruin crowned an eminence, and everywhere the eye discovered some charming perspective, and the imagination carried one beyond the sight; for who can contemplate an unknown country without planting some romance in it, especially if that country be Corsica?

The isles, half lost among the waves, appeared to me like hermits of the sea. Every one of them had a different aspect, a distinctive character, a sort of physiognomy which engraves itself strongly on the memory, and which is seldom seen on the mainland, where the plains are so similar in their uniformity.

The isles of the Mediterranean, moreover, have a peculiar and altogether exceptional interest. From our infancy we have been familiar with their names and their histories; and what the books of the student have not taught us, we have afterwards earned from descriptive romances, and some of us by our own travels. The barque of commerce and the tourist-laden packet-boat are crossing incessantly between France and Ausonia’s ever classic land, where the inhabitants of the north, tired of their fogs and mists, come to reanimate themselves, and get rid of their melancholy humours.

Corsica enjoys all the advantages of a French Government, but the manners of its natives remind one of the ferocity of past ages, when every man took the law into his own hands. It is remarkable that the nature of the soil and vegetation much resembles the customs of the country. These are obstacles which will long interfere with the progress of civilization. I will not say that little is known about Corsica, but rather that she occupies but little attention.

Much more must be done to lift the mysterious veil that covers this country, and which favours the accomplishment of acts quite at variance with the times. The Italy we knew by the descriptions of Goethe appeared to us more poetic than that which we now visit and observe for ourselves, as do our sleeping dreams and waking visions than the objects actually presented to our sight. For this reason, I suppose, it might be that, fatigued with the bright aspect of the shore, my mind wandered into the interior of the island, under the aged trees of the virgin forests, yet untouched by the woodman’s axe, the intricacies of which have served as the refuge of the bandit from the pursuits of justice, and the “vendetta” from their bitter foes.

Venerable Kyrnos! possessing still the woods which were the admiration of antiquity! Seneca knew them, when in his exile he wandered along your shores, and imbibed the inspirations which dictated his “Consolatio ad Helviam.” Then already the God of War had lit up your shades and trampled down your harvests; when the Ligurians, the Etruscans, the Carthaginians, the Romans, successively invaded your territories, and fought many a sanguinary battle for their possession. Here Belisarius gave combat to the Vandals. Here reigned by turns the Goths, the Lombards, the Francs, the Saracens, succeeded by the Pisans and the Genoises. Although thus often the object of dispute, this island subsequently sank into repose and oblivion, though destined to give birth to the Imperial Eagle, whose thunderbolts lightened the whole world.

My historical reverie was broken by Captain D, who directed my attention to the little city of Bonifacio, backed by a calcareous rock, which made it very distinguishable. Its construction evinces the strategic talent of the Tuscan Marquis Bonifacio, who gave it his own name, on founding it after his triumphant return from Africa. When we passed it Neptune was kinder to us than usual, and we sailed along a sea of glass. A multitude of islands, far and near, large and small, showed themselves above the limpid waves, through which the course of the “Virgilio” resembled a summer’s sail upon a Swiss lake, more than an October voyage through one of the most dangerous passages of the Mediterranean Sea.

Leaving upon our right the granite Isle of Cavallo, we reached one of the group of the Lavezzi, so sadly celebrated by the loss of the “Semillante.” This beautiful frigate, laden with munitions of war, and having on board 1000 soldiers and a numerons crew, was wrecked here on her voyage to the Crimea. This inhospitable rock stands like a funeral monument, pointing out the dangers which menace the mariner on his entrance into these straits. Not a single man survived the disaster. A few lifeless bodies were the dumb messengers which told the tale of this frightful catastrophe. Every soldier who goes to the wars, knows that he may be their victim; but it is sad that he should find an obscure grave in the deep, when he thought to die the death of the brave in some glorious struggle on the battle-field.

The island of Santa Maria, which shortly came in sight, was the first object which interrupted these trite reflections. An old lighthouse presides over the flat and sandy shore, recognizable by its yellowish tinge, which distinguishes it from the steep coasts of Razzoli and Budelli.

Leaving behind us the Barrettini, whence the northern point of La Maddalena is just visible, though partly concealed by the Isle of Sparagi, which seems to bar the passage, we entered a bay from which no outlet was visible. We had coasted for half-an-hour the ancient Phintonis, whose perpendicular cliffs rose boldly before us, when the “Virgilio” was veered to the eastward, and traversed the little arm of sea which separates the isle from Sardinia. We then found ourselves in a sort of basin, surrounded by islands. Crowned with forts, St. Stephano lay on our right hand; before us Caprera, backed by the distant mountains of Sardinia, and to our left the smiling coast of La Maddalena, the town of the same name appearing in sight from the roads, and forming a little amphitheatre from the shore. The wheels of the “Virgilio” revolved with less and less velocity, and then stopped altogether, and we were at our destination.

When the reader learns that the only communication between the island and the mainland is by one monthly voyage, he will not be surprised that our arrival was an important event in the eyes of the inhabitants, and that the shore was covered with a crowd of people. If the departure from Genoa was a tumultuous scene, our arrival here greatly surpassed it. The thought of having escaped all the dangers of the sea, and the pleasure of again placing foot upon terra firma, in the midst of their relations and friends, diffused a universal joy amongst the passengers. As to the islanders, they set at nought the orders of the Captain, and in spite of the rough opposition of the crew, they tumbled by hundreds over the bulwarks on to the deck; some seeking friends, others goods which they had been long expecting, and some asking political news, and quarrelling for the papers.

My companion had not foreseen this tumult, and the delay it would cause us in landing. To avoid the throng I retired to the after-part of the vessel. As I was watching the little port and the fishing craft at anchor there, Captain D. approached me with an air of pleasure, and pointing to a boat, he exclaimed, “Look, Madam, there is Garibaldi! He will soon be on board! With what joy shall I again clasp the hand of that brave man!”

Notwithstanding the multitude of boats going to and coming from the shore with passengers, I could readily distinguish the General, standing upright, one hand holding a rope. He balanced himself with perfect ease at the prow of his light bark, which was managed. by a sailor and a very handsome youth.

The aspect of the man so well known in America and Europe was not strange to me. I had seen him at the time when the eyes of all Italy were fixed upon him. In those days of anxiety and hope –when he came to Rome to defend her from the yoke which menaced her – his appearance then filled me with enthusiasm. Now, it moved me to the bottom of my soul! for since 1849 I had been initiated into all the particulars of his life, and comprehended the real value of such a man; and I may truly say that his noble and serious countenance bore in it the evidence of his always grand and adventurous, and sometimes even tragic, history. I therefore contemplated him, not with the fanatic enthusiasm which idealises its object, but with the consciousness of his actual merits, and the certainty of his being a hero whose self-denial and magnanimity equalled his courage; and my entire attention was concentrated on his figure, from the time he was pointed out to me, until he stepped on deck among the concourse which surrounded him.

Although I had requested Captain D. not to name me to the General till some of the confusion was over, it was scarcely a quarter of an hour before he came to say that Garibaldi desired to be presented to me. We went into the ladies’ cabin, and there amidst noise and bustle I exchanged my first words with the illustrious warrior. He inspired me at once with such a feeling of confidence that I seemed to be meeting an old friend; and this arose, no doubt, from the cordiality of his reception and the sympathy which a fine and sincere character is sure to call forth.

I very soon told him the object of my voyage, in which he alone could assist me; but hearing from him that the documents I wanted were no longer in his possession, I felt much discouraged. However, I could not regret having undertaken my enterprise, as it had accomplished one of the most ardent wishes of my heart. I had become personally acquainted with the man whose great character had occupied my thoughts for many years, and it was with true enjoyment that I heard his opinion of the existing state of Italy, and the critical situation of England in regard to the Indian Mutiny. I was agreeably surprised at the admiration he expressed for my country – the more so, as it is not common to find an oppressed people forming an impartial judgment of a great and free nation.

Garibaldi’s eloquence became more and more animated as the conversation proceeded, and more and more captivating as he spoke of the past and the future of Italy. The fire of patriotism glowed in his lively but earnest face; his open countenance and classic features revealing, in one expressive whole, the goodness and the strength of his character. One could not but perceive what must be the effect of this powerful individuality upon the masses. Such a leader electrifies his troops, in communicating to them, by example, the heroism he feels himself!

“But where, Madame, do you think of taking up your abode?” said the General, when Captain D. came to tell us it was now possible to go on shore.

“My friend tells me there is an inn for strangers,” replied I, turning to Captain D. “Certainly, Ma’am, we shall find two rooms at Ruffo’s.”

“Madame,” interrupted the General, “it is quite impossible for you to go into such a place. Let me beg you to come to my house. I regret that I shall not be able to receive you as you deserve, but all I can do is at your service, and I offer it most cordially. Allow me to conduct you to my boat, and before sunset we shall be at my house in Caprera.”

The tone in which Garibaldi pronounced these words was so persuasive, that I found it difficult to reply by a refusal. I did so, however, being determined to visit La Maddalena, and very unwilling to incommode him. Promising, then, to devote the morrow to a visit to him, he pointed out to me his retreat, situated on the point of Caprera, where the shore, to the east, seemed to shut in the transparent lake on which we were now at anchor. At a short distance from the beach, in a delightful solitude, I discovered a white house, backed by a wall of granite rock.

Three o’clock now struck, and it was full time for us to depart; but, before leaving the ship, he advanced towards me with the youth of whom mention has already been made: “You must also know my son Menotti. Some people reproach him with having the air and robust form of a sailor. For myself, I know too well the value of good health, not to encourage him in all manly exercises which strengthen the body, even at the sacrifice, perhaps, of some of that extreme elegance which the world so much delights in!”

I replied, “It seems to me, General, that you have perfectly attained your end, and that your son is endowed with that strength which does not exclude grace,” and held out my hand to the young Hercules, whose frank air and noble carriage had already attracted my admiration. Once in the boat, a few strokes of Menotti’s vigorous oar brought us to the strand, where we parted with a promise to be early on the morrow at the “Punta della Moneta,” the south-eastern extremity of La Maddalena, where a very narrow arm of sea separates her from Caprera.

“And what is to become of us, now that we have declined, rather inconsiderately, the hospitality which was so freely offered us?” was the ironic exclamation of my companion, as he followed the porter who carried our luggage through the streets of the mean little town.

“We shall soon know our fate,” said I, as our guide turned into a house on the right hand. “A most promising entrance,” grumbled my companion, looking up a staircase as straight and almost as steep as a ladder. Some halfnaked children barred our progress. “Whew! what a smell of garlick! enough to make the whole English army draw back!” cried Captain D, on opening the door of a room where we were encountered by a number of women.

“Have you two rooms to let?” he asked, casting a sceptical glance around the chamber which we now entered, and where we saw an immense bed and an enormous table, round which were seated many of the “Virgilio’s” passengers, recruiting themselves after the effects of the sea, by eating, with an excellent appetite, everything that was set before them. The women pushed us into an adjacent closet, saying, “You may lodge there.” “But the second room?” asked the Captain, with visible anxiety. “These people are going away again in the steamer, and then you can take their place,” was the women’s reply, speaking all together.

Our doom was pronounced-we could only resign ourselves to it. The open street was the sole alternative.

Our eyes sought in vain even the most indispensable articles of furniture, and always after every glance they rested on the gigantic bed, which was covered with dishes and glasses and tureens, which were almost lost in heaps of boots and shoes and wretched rags of clothing, in which heterogeneous amalgam seemed to be everything for which there was no other place.

Nor were live objects wanting. At one corner a poor bitch was suckling her litter; at another a hen sheltered her brood under her wing, and near them a fine pigeon cooed to his mate.

What repose could be expected from such a couch, which, no doubt, was also the habitation of other and smaller members of the animal kingdom?

I stood stupified and horror-stricken for some moments, and then turned away and followed Captain D., who said that, since we were condemned to such a fate, we had better at least employ the remaining hours of daylight in seeking our fellow-countrymen whom we intended to visit. Desiring that the rooms should be put into some kind of order while we were away, we obtained a guide to Captain R.’s dwelling, and soon arrived in front of a pretty house, situated at the end of a promontory, about a gunshot from the quay. From my first arrival I had remarked this house, the harmonious lines of its architecture, the colour of its walls, and particularly its fine situation, fronting the sea, and commanding a splendid view on every side.

The loud barking of two large hounds gave notice of the presence of strangers, but the zeal of the two Cerberi was soon quieted by a servant, who asked us to enter. Captain R. came to the door, and said that his dog, “Terrible,” did not know what to make of so unaccustomed an event as a visitor, and was rather disposed to give us a “terrible” reception. “His master, however, is more friendly,” replied I, as I returned the pressure of the old gentleman’s hand, and took the seat to which he led me.

Never did I feel more sensible of the truth of the old saying, that “the friends of our friends are our friends,” for, without introduction, or even sufficient excuse, I was intruding on an entire stranger, of whose existence, forty-eight hours ago, I was perfectly ignorant, and yet the mere naming of a mutual friend had produced in a moment something very like intimacy between us.

I gathered from my worthy host’s conversation that, after a brilliant career in the British navy, he had visited many places in his own yacht until he had been tempted by the splendid climate, and the great opportunities for hunting and fishing, to establish himself in this island; and here for many years he had now passed a life, divided between the quiet pleasures of reading, and the gentle labours of his vineyard and garden. It cannot be said that solitude weakens and enervates, for a more fresh-spirited and hardy old man I never beheld; and notwithstanding his seventy years, his firm slim figure, the fire of his sharp eyes, and the energy of his every movement, might raise the envy of many a much younger man.

The sight of a fresh heap of newspapers and letters, which covered the table, made me fear that we had disturbed our host by our unauthorized visit, and we therefore prepared to depart, asking him if he thought we might venture to call upon Mr. and Mrs. C. “Certainly,” he replied; “and if you are not afraid of my little boat, it is quite at your service to take you to the Punta della Moneta. It will save you time, and you have not much to lose.” With these words he conducted us to the landingplace below, and accompanied by his boatman, Giovanni, we stepped on board the boat.

It was the most beautiful part of the day, when the departing rays of the sun had but a short hour left to gild the valleys with their glow; though even after the moment of setting they would still gladden the highest tops of the mountains, until, bathed in a sea of purple, they abandon the earth to the shadows of night.

Never saw I a more translucent sea! never a more resplendent sky, and never in Greece or Italy had I inhaled a milder air! But it is not in the vegetation, the luxuriant meads, or the autumnal tints of the rich woods, that the stranger should find his chief inducement to visit this country. Wherever the eye turns, it rests on gigantic and fantastically formed rocks, whose inhospitable steeps forbid even the use of their scanty herbage, and give the northern stranger an idea of a comfortless desert. But the eye of the poet, and the searching glance of the geologist, will view these majestic masses with the purest delight, whether it be to seek in them the traces of beauty, or the evidences of the God-written annals of nature.

We were now coasting the southern shore of La Maddalena, having on our right the Isle of St. Stephano, until Caprera revealed to our sight all the asperities and the depths of her abrupt declivities, illumined by the roseate reflections of sunset. In about an hour we reached the Punta della Moneta, at the extremity of which stood the white mansion of Mr. C, built in the Moorish style, and we arrived there, after a short walk along a picturesque terrace, where bloomed the cactus and the Indian fig.

Giovanni went forward to announce us. Mrs. C is one of those extraordinary women whom England alone can create, and of whom I have found examples in regions the most distant from home. She advanced towards us as far as the door of her romantic habitation, begged us to enter a pretty room even with the terrace, and expressed her regret that her husband was not there to receive us. Mrs. C. might be about five-and-forty, still very agreeable in person, and her manners evidenced the distinction of her birth. She had resided here for twenty-five years, and I believe that some catastrophe had condemned her to this voluntary exile. I longed to know the mystery of this destiny, but all I could learn was that she ordinarily accompanied her husband on his long excursions on horseback and in the chase, and even in his fishing voyages a passion for which they both possessed, to the extent of being several days absent on the open sea. Mrs. C. seemed to penetrate my wishes, but she only gratified them so far as to tell me that by birth she was a lady, by choice a gipsy, and by necessity a farmer’s wife. I can only say that her behaviour evinced perfect contentment; and, notwithstanding the complete isolation in which she was placed, without children and without domestics, her life, perhaps, affords more real interest than the existence of some of our queens of fashion, who purchase their triumphs at the cost of so many frivolous but imperious duties. Exclusively devoted to the care of her household and farm, she had formed for herself so extended a circle of activity, that ennui could never reach her. I was told that for seventeen years she had never set foot in the town of La Maddalena. A pleasant fireplace, a choice library, a writing-table covered with books and papers, showed that many calm evenings might be enjoyed in this room.

I inquired of Mrs. C the qualities of the small Sardinian horses, and she assured me they deserved the renown they had obtained. “Their price,” she said, “never exceeds 200 francs, and their keep is about 150 francs a-year. They require but little care, and can support the greatest fatigue, which I attribute to their breed and their food, composed, like that of the Arabian, of straw and barley. If you will place yourself at the window, I will show you my own miniature charger.”

She went out into the garden, and one call of her well-known voice served to bring from his stall the prettiest little horse of dappled grey. He put up his bright eye, and shook his head with a proud but docile air, and followed his mistress, who, having a sieve in her hand, attracted the attention of all the other quadrupeds and all the fowls of the farmyard. Two dogs came out to greet her, wagging their tails. Some pigs, of a kind peculiar to Sardinia, a flight of pigeons, and many fowls with bright red crests, came running to pick up the grains that fell. A bank of laurels, roses, and exotic plants formed the frame of this living picture, the serene beauty of which reminded one of the pastoral manners of the golden age.

Once more in our boat, which glided in its silent course over the wave less water, and the night having by degrees confused every object and every colour in one sombre uniformity, I pleased myself by considering the country life I had just witnessed, and its traces on my mind were more poetic and enchanting than even the reality.

“I do not know,” said I to my companion, “what have been the trials to which Mrs. C. has been subjected, but I would accept her past, with all its griefs, if I could at such a price purchase her present happiness.” “Particularly this evening,” replied the Captain, who was thinking of our return to the inn! “Stop, Giovanni,” continued he, as a boat crossed us; “I think that is a fishing boat, and we may perhaps add something to our rather problematical supper.”

Such an idea was not at all to be despised; particularly as the fishermen had caught but three red mullets, and we at once secured them for a small coin, which they thankfully took in exchange.

It was late when we entered the town, and on reaching the inn we were disagreeably surprised at finding the large room full of travellers, and the second exactly as we had left it! Captain D. angrily demanded why the rooms had not been prepared and reserved for us. His words seemed rather to confuse the eldest of our hostesses, an old matron, as thin as a spindle, and enveloped in a brown cloak. She asked us, in a dolorous tone, to “pardon her poor daughters, who must have been out of their minds to promise us the second room, as it belonged to an engineer and his family”! At this the Captain’s choler became more violent, and his reproaches, mingled with the excuses of the daughters and the protestations of their mother, formed a “crescendo,” which soon became a “fortissimo,” that almost split the tympanum of our ears.

“Send then for Pietro Susini,” said Captain D, “and he must find us another lodging;” and with this he began to dissect a tough fowl, which he declared must be the progenitor of all the fowls in the place, and, at last, told the old woman to bring some bread, if nothing else was to be had; on which she placed before us some baked paste, as hard as a biscuit, saying, “Our bread is all gone, and there are no bakers here. Every family bakes for itself every Saturday, and when they have no more, they do as well as they can, with chesnuts, or potatoes, or maize.”

“Madame,” said my friend, smiling, “I warned you that we should have to live like Crusoe in his island.” However, our hostess now brought us some fine chesnuts and a straw-covered flask of excellent wine, the first glass of which restored the Captain’s equanimity. The women, fearing to lose us, tried all their eloquence to persuade us that one room was enough; but the arrival of Pietro Susini put an end to their entreaties. He told us there were apartments to be had in the house of the sisters Fazio; but, up to the last moment, we had almost a battle to get away.

I should have said before, that the Captain had a letter of introduction to Signor Susini, who was one of the authorities of the place. “I am about to take you to some very respectable people,” said he, as we entered a house. He opened a door, and we found ourselves in a large apartment, the ceiling of which was formed of canes, interlaced in a pattern. Three women received us courteously. Susini assured us that we should here find a quiet and propriety which was to be met with in few houses in the island. They introduced me into a small chamber, opening out of the vestibule. Here there was a bed, with a damask coverlid and white curtains, a table, and an old prie-Dieu, and the rest of the space was not much more than my trunk required.

“There is another room for the Captain,” said Susini; “and if you want anything else, you have only to ask for it.” “Quite true,” said one of the sisters; “everything we have is at your disposal. Our house is small, but our hearts are large!”

The time for tea having arrived, I began to make my preparations, and I presumed that these large-hearted ladies would at least furnish me with some hot water – but no! They allowed me to light my spirit lamp; and instead of offering me any assistance, they only looked on with surprise, and afterwards asked to partake of a beverage which was entirely unknown to them.

After tea Captain D retired to his cell. The sound of his boots as he threw them off, and presently an energetic snore, showed that he had already forgotten his fatigues in sleep. The ladies wished me good night, and left me to the free use of the room, of which I profited to write up my journal.

The consciousness of being thus alone in a strange place, at an hour of universal repose, always awakes in me a peculiar sensation. Fancy is in the ascendant, and runs away with me; and my thoughts not being restrained by any external obstacle, outstrip in rapid flight both time and space.

Having written for a while, I allowed myself to be tempted by the bright moonlight to walk out into the free air, and enjoy the splendour of a night so radiant. The house of the sisters Fazio was situated on the slope of a hill, and at a few steps from the door I obtained an extensive view, illumined by the beams of the beautiful planet. This demi-light, which gives so great a charm to places we love, diffuses a still greater illusion over an unknown country, which our imagination may embellish as it will. The silence of nature was uninterrupted either by the bark of a dog, the cry of an owl, or the noise of the sea waves. A calm so profound reigned over the sleeping isle, that the most sensitive ear would have failed to distinguish a single sound from any one of the multitude who reposed at this solemn hour on its breast. One might have thought that all life was concentred in the vegetable kingdom, which now filled the air with perfumes the most delicious.

I followed the path which led to the old and abandoned fort of La Guardia Vecchia, until it disappeared amidst a chaos of stones and rubbish. I was afraid of going farther, and I sat me down on a block of granite. The moon was now less brilliant, and some rather ominous clouds appeared at all points of the horizon. The sea, shut in by numerous mountains, isles, and promontories, formed itself into basins of different shapes and extent.

And in all this solitude, thought I, there is so much security, that a whole population is sleeping in peace, with open doors, under the protection of Heaven; and I, a stranger, am wandering about at midnight wherever caprice leads me! I then thought of the wide expanse of sea and land which separated me from my home. Seized, and by degrees absorbed by this impression of solitude, my mind was carried back from age to age, even to the Creation; and the sight of all these islands and mountains awoke in me a vision of that unknown time, when the war of elements overthrew the order of our sphere, making islands rise from the bosom of the deep, and forming seas in the midst of continents.

The probability seems to be that Sardinia was once the centre of all these isles, which no doubt partook her destiny. Let us go back only to what history has chronicled. Sardinia has played but a small political part since the time of Tiberius Gracchus; not because she is insignificant in herself, but because she has had the lot of many men who, endowed with all the gifts of Nature, have been so placed by circumstances as to be unable to develop their qualities, and are thus the victims of that injustice which in all ranks of society exercises an inexorable despotism!

As everything which is concealed has an attraction at once strange and pleasant, I plunged deeper and deeper into thought, and Heaven knows how far I might have gone had not a noise of falling stones aroused me. I turned quickly round, and beheld the tall figure of a man, who, descending the hill, advanced towards me with a firm step.

“Salute,” said I to the unknown; who, armed with no weapon more formidable than a walkingstick, inspired me with confidence rather than with fear.

“Salute,” replied (according to the custom of the country) the voice of an old man, with an accent so sympathetic, that I determined to profit by the rencontre in finding the shortest way home. Scarcely had the stranger recovered his surprise at my unexpected presence, than he asked what could have caused my being alone in such a place at such an hour.

“Merely,” I answered, “that I might contemplate by moonlight the different points of your island! and you, an aged man, what could be your inducement to leave a comfortable home, and make a nocturnal excursion, so fatiguing as it must be in these mountain paths?”

“Alas! where is my comfortable home?” cried the old man, with a sigh. “Look, Signora mia,” continued he after a pause, and uncovering his head, displaying his snow-white hair, and turning his majestic figure towards me, “Michele Zicaro can count ninety-eight years, but it is not the weight of age, but of grief and cruel losses, that bears him down.”

Touched with compassion at these words, I asked, “Have you no children, no grandchildren, whose affection might soothe your sorrows?”

“I have possessed all, but to lose all, and to pass in misery and bereavement a deplorable old age. The town which now extends itself along the shore, once crowned the hill which still retains the name of Santa Trinità, and where the vestiges of the old buildings may yet be seen. That was the scene of my earliest recollections; there it was that we were kept by fear of the Turks.

Halfa century and more has since passed over us, but there are even now moments when I can fancy I hear the silver sound of the church bell at daybreak, calling to their work all the inhabitants of the place, for every one felt himself bound to work at the erection of the fort Della Camicia,’ our only ramparts for the preservation of our goods, and of the honour of our wives, and daughters, and sisters. Every one in the island, not only the young and strong men, but boys and girls, women and aged men, lent a hand to this work of defence, on which our safety so greatly depended. I think I now see this band of voluntary labourers hastening to the place of their appointed work. Yes, Signora, it was a time of fatigue, excitement, and anguish.

They called Michele Zicaro the happiest man in La Maddalena; and indeed he really was so, for the pastures of the island did not suffice for his numerous herds, and they were sometimes sent to graze the green meadows of the Barrettini. A worthy circle partook my happiness, in the midst of a group of children who prospered around me.

Holy Virgin! shall I never lose the remembrance of that terrible day, which changed all my joys into mourning! It was a beautiful spring morning: we were returning from church, where my eldest daughter had just received the nuptial benediction, and, agreeably with an old custom here, we were descending towards the beach, to finish the fête by a marriage feast, with a number of joyous guests. Suddenly as we crossed a ravine we found ourselves surrounded by a horde of pirates, who had just landed. After a vain and useless resistance, for our enemies out-numbered us greatly, and were well armed, I was overthrown with such violence, that I lost my senses, and was unable to see any more. After a while I recovered consciousness, and my ear was struck by the sounds of rage and distress. I comprehended at once all that had passed; my unfortunate companions were standing on the shore in an attitude of despair, pointing to a Turkish galley in the distance, in full sail, laden with women and booty. They were our wives and daughters, the captives of their ravishers.”

“All your children! were they all taken?” I asked of the old man, whose emotions had forced him to break off his recital.

“There remained to me two sons,” he replied, with a sigh, “but they also were soon taken from me. My wounds were scarcely healed when I received the news that the elder of them had perished by shipwreck off the northern coast of Africa! As to the younger, he also would be a sailor. He was deaf to my prayers, and would not take warning by his brother’s fate! He persisted in his choice. The British fleet appeared in our waters, and this circumstance awoke the ambition of the lad to such a degree that he could not rest till he had obtained a berth in the Admiral’s own ship. The moment of his departure is always before my eyes! I think I again receive the last adieu of my darling boy, my last and only hope! He was radiant with joy, speaking only of success and speedy return! He embraced me tenderly, and tried to console me, but I was sad and downcast, and foresaw a further misfortune! Penetrated with this presentiment, I stood watching the disappearance of the last sail of this splendid squadron, whose presence here had brought back security to our coasts. The brilliant victory over the French and Spanish fleets which was purchased by the death of the British hero deprived the poor Zicaro of his last child! My boy fell in the battle of Trafalgar!”

“He partook, then, of the fate of Nelson.”

“Yes, Signora; you have named the great man whose example enchanted my son; and what a man he was! He first showed his genius at Aboukir, and, like a meteor, he arose in the East, and after a rapid career he sank, like the sun, in splendour, in the West.”

“Did you know the Admiral personally?”

“I not only knew him well, but loved him well,” replied the old man, with a proud air. “No one could approach him but with respect amounting almost to reverence! Every time he set foot on our shore, he remained some time with us, and with the kindness inherent in his nature he questioned us all of our families and affairs. Often did he mount the hills that looked over the sea, and as he enjoyed the charming prospect, he made me recount to him the incidents of my life, and the history of our little isle. The church of La Maddalena possesses a souvenir of his generosity, in two fine candelabra and a chalice of silver. When he took leave of us, he promised that, if he returned victorious from the battle he projected, he would make the island a present equal in value to a well laden brigantine. Ah, Signora, let me assure you, it is not the loss of this rich gift that I regret-what I deplore is the premature death of so great a man, and of my poor boy!”

“Zicaro, at that epoch you were in the full power of manhood, and did you not again marry?”

“Ah, Signora, I did; and during that second marriage I saw a new spring time around me, till that terrible malady, which you also must know well, decimated our population, and deprived me of wife and children at once.”

“Indeed! and was the cholera so violent here?” “Alas, yes; and no sooner did it appear than all our physicians abandoned us to our fate. The sick and the dying were deprived of all help, and those who escaped the disease had to support the pangs of hunger afterwards, for the authorities of the town interdicted the importation of everything. Those who had not the means of escaping to Sardinia must have died of famine, had not the Government interfered and taken measures to supply us with food. In a few days we celebrate the anniversary of the dead – a day consecrated by the Church to a visit to the tombs, which we then garland with fresh flowers every year. I am now descending from the cemetery, where I have been to prepare it for this ceremony. In that sad place, where all my happiness lies buried, I have passed a great part of the night, absorbed in grief, and in the recapitulation of my successive bereavements.”

This recital threw me into rather a sad meditation. “So then,” thought I, “this small spot of earth, little known and less visited, has not escaped the vicissitudes of fate. Its shores, in appearance so tranquil, have been the theatre of many sanguinary invasions. Its people have been the victims of disease. They have endured famine, and here, as everywhere else, the passions have had their sway. The echoes of European wars have reverberated from these rocks, and the memory of the naval hero of England lives in the hearts of these islanders, mingled with gratitude for the benefits he conferred on them. And yet their annals have still to be written, and no bard has yet sung them. All that has escaped oblivion, lives only in the excited brain and the broken heart of a poor nonagenarian, who must himself soon pass away and his recollections be buried in his grave.

Such were my thoughts as I again crossed the threshold of the house and sought my chamber.

If my rencontre with Zicaro had not been enough to banish sleep, my surroundings would have sufficed. A simple cloth curtain separated my room from the bed of the three ladies, so that I was the compulsory auditor of a sleeping monologue from one, the constant snoring of the second, and the asthmatic cough of the third, and all these sounds were mixed with the clucking of the fowls which shared their apartment. But the noise which troubled me most was the patter of a shower of rain, which threatened to spoil our morrow’s excursion to Caprera. I listened to it with some anxiety, as it sometimes seemed to diminish and then again increase, until I heard distinctly the footsteps of somebody in the vestibule, who appeared to be groping in the dark for something he could not find. Suddenly there was a violent crash, accompanied by a cry of alarm, which made me jump.

“Gracious heavens!” cried all the women at once, “what can have happened?” “What can have happened?” re-echoed a voice which I immediately recognised, “come here and see, and help me out.”

“The Captain is all in the cellar,” exclaimed the youngest of the three. “Only half,” answered my lively friend; “the superior half is still in air, though the inferior hangs in vacuo.”

During this short colloquy the women had struck a light, and put on in haste a few indispensable garments, before they ran to his rescue. I should not have been a woman had I not given way to my curiosity, and I peeped through my half-opened door to ascertain with my own eyes what had occurred. In spite of the real interest I felt in his mishap, I found it impossible to resist a loud fit of laughter when I saw the three sisters, in most fantastic costumes, using all their endeavours to release their guest from the trap in which he was caught.

“In the name of all the saints!” said he, “one might as well live in the time of Don Quixote and the knights-errant, if one cannot cross the room in search of one’s travelling-bag without falling into an ambush! Wishing to get at my coffee to prepare it for the morning, the floor gave way, and I fell”

“Only into the cellar!” interrupted the women.

“Only!” replied he. “Well, thank heaven, I am no worse off than the Holy Father himself was when he visited the Convent of St. Agnes.” With which words he disappeared into his cell.

I afterwards found that his allusion was to a story of the Pope and his attendant dignitaries having been precipitated through the floor of the refectory of a convent when they were feasted by the monks, without any more disastrous consequences than attended the captain’s fall.

CHAPTER II

The Island of Caprera and its Cincinnatus

THE rain had scarcely ceased. The dull sky, still covered with clouds, lay heavy on the horizon, when, determined to brave the weather, and equipped accordingly, we quitted our lodging at eight o’clock in the morning.

“The roads are in too bad a condition to allow you to go by land to the Punta della Moneta,” said our cicerone Susini, “and therefore I have bespoken Maestro Giulio’s boat to carry you direct to Caprera, and he will himself take charge of it.”

The thick mud which covered the few streets we had to pass through to the shore completely justified Susini’s words. We therefore gladly availed ourselves of his plan, and on the beach we saw Giulio’s boat preparing for our reception.

As we walked down, I said to Susini, “I see that you will never want materials for your houses, since you build them of the very granite on which you lay their foundations;” for I observed that a new building was rising on the rock, out of which the masons were at the same time quarrying stones for its walls.

“Most of these islands,” he replied, “are immense quarries of granite, but it varies much in quality and value. That of this island is inferior, but some of them produce a kind which is rich in spar, and has a roseate tinge, and may be compared with any that comes from Egypt. The isle ‘Dei Cavalli,’ which you passed on your voyage, is celebrated for its ancient Roman quarries, where were found, as also at Testa, in Sardinia, some columns shaped out in the rough, and others nearly finished. We know from history that the Pisans took from the peninsula of Testa the columns of their church of San Giovanni, and it is very probable that the peristyle of the Pantheon came from the same source.”

The arrival of Maestro Giulio interrupted our conversation. He came to tell us that the boat was quite ready, and we took our places in it at once, together with his nephew and three sons all with fowling-pieces in their hands and dogs at their side, and all going over to Caprera for a day’s sport. Susini, wishing us a good voyage, promised to meet us in the evening at the Punta della Moneta.

* * *

“What boat is that, tacking across the strait?” asked Captain D.

“It must be the General’s,” said Giulio. “You are right,” replied the Captain, “for he promised to meet us at nine o’clock, and there, no doubt, he is, with his accustomed panctuality.”

A long distance, however, lay between us and the white sail that had attracted the sharp eye of my companion, and I had time and leisure enough for observing the capricious forms of the rocks as we rowed by them. On the Sardinian coast, just opposite La Maddalena, there was one which particularly amused me. It was called “Capo dell’Orso,” for on its top was a block of stone that precisely resembled a bear sitting on its haunches. When we consider that this cape has the same name in the geography of Ptolemy, we must conclude that its form was the same 2000 years ago; and as it must be the action of the atmosphere which in the course of many centuries has sculptured these solid rocks into the forms they bear, the origin of these curious similitudes is lost in the dark night of time.

While the sight of scenery so new to me was thus delighting my mind, the boat we had seen at a distance had been gradually approaching us, and we were very soon able to distinguish the General sitting at the helm. Shortly afterwards we were near enough to exchange salutations. “I think,” said Captain D., “that we shall do best by remaining in Giulio’s boat, for the wind is high, and it is always difficult to change when there is much sea.” “There is not so much as to oblige us to refuse the General’s civility,” replied I; and in a few minutes we had stepped from our poor skiff into the General’s beautiful bark; and when I expressed my regret that he should lose so much of his precious time, he replied, with naïve grace, “There will only be one workman less at my house to-day, and such a visit as yours is a pleasant excuse for a holiday. I now only wage war with stone, and see,” showing his labour-roughened hand, “if a day’s rest is not desirable for the poor builder!”

After a short run, the swift boat entered a little harbour, formed by nature; and crossing in a few paces the beach, we trod the odoriferous soil and the green close sward of Caprera.

But how different from her sister island! No picturesque fishing boat gives life to her waters-no pleasant little spot appears along her shores-no ruined forts crown her heights but one mountain chain upon another raises its rugged masses in amphitheatric form before the wondering eye of the stranger! All that surrounds him here is severe and vast, as if Nature had purposely designed it for the residence of the Cincinnatus of our day! The mastic and the arbutus, the myrtle and the heath, and a number of aromatic plants, group themselves among the rocks and over the turf on which, in ascents more or less steep, you walk from the sea to the habitation of Garibaldi.

A short half-hour brought us to the enclosure of flower-beds which extends along the front of the house. Several dogs ran out to welcome their master with the violent expression of their joy, and to be rewarded by his caresses.

“Those must be the ruins of your first dwelling,” said I, pointing to a fallen log house.

“Of my second,” he replied. “My first was a simple sail, of which I made a tent; but if you will permit me, I will now conduct you into my third, which I have built of more durable materials. It has, as you see, but one storey, and I have copied the style of the South American villas, and covered it with a flat roof, which forms a terrace walk.”

The beautiful appearance of this mode of construction is extremely agreeable to the eye; and, on entering the house, I found that the interior corresponded in character with the façade-a praise which cannot always be awarded to our modern fabrics. Every room was ample and well ventilated. The harmony of their proportions proved that the architect thought more of producing becoming apartments than of submitting to the mere rules of his art.

In a room which had been occupied by one of the two friends who shared the General’s rural life, I observed a little collection of the flags of several nations; and, on inquiring the meaning of these souvenirs of war, he seemed anxious to avoid a reply, and presently left the room, for he is not one of those who are the recounters of their own successes.

These flags, which I now examined more attentively, were the trophies of his triumphs, and recalled many a brilliant episode in his heroic career. I fixed my eye upon the standard of Monte Video, presented to her brave defender after the battle of St. Antonio. It was on the 8th July, 1846 –a memorable day – on which Garibaldi, at the head of 200 Italians, found himself surrounded by troops, consisting of 1200 men, under the command of General Gomez. Instead of standing on the defensive, which, under like circumstances, no chief could have been blamed for doing, he attacked, with his handful of followers, this force so greatly superior in number, and after a conflict of five hours, Gomez, with his infantry in disorder, and his cavalry in confusion, abandoned the field to its conqueror!

The contemplation of this flag brought also to my mind Alexander Dumas’s little work of “Monte Video, ou la nouvelle Troye,” in which he renders such transcendent justice to its dauntless defender, proclaiming with enthusiasm his superiority as a warrior and a man! The facts related in that book are, as Garibaldi himself allows, quite true; but it seems that the praises lavished on him appeared to him excessive, and he was thus prevented from thanking its author for his work.

Having gone over the house, the General invited us to take some refreshment; but we had so little time, and I was so anxious to walk over his grounds, that I proposed starting at once on this expedition. “At least,” said he, “let me introduce you first to my daughter Teresa,” and he left the room in search of her.

I threw a rapid glance over his library. To my mind a man’s library is the best index to the character of him who formed it; for books are not like unwelcome visitors – they do not come unbidden, and only surround those who seek them and love them. This little collection was composed chiefly of works as solid as their possessor, whom they have followed to the wild shores of Caprera, to charm his short intervals of leisure. Side by side with the best treatises on the art of war and navigation, I saw the names of Shakspeare, Byron, and Young; farther on were the most esteemed works on natural philosophy and science, the “Cosmos” of the great German thinker, the Ethicks of Plutarch, the Discourses of Bossuet, and the delightful Fables of La Fontaine, which conceal so much of the profound under the disguise of naïveté.

The entrance of the youthful Teresa ended my literary review. I saluted with much interest this beautiful girl, in whose regular features I recognized the traces of her father’s countenance, while the flexible firmness of their movements reminded me of the Brazilian origin of her mother. Never did a complexion of golden brown so harmonize with light-coloured hair. Was it the softness of her dark chesnut coloured eye, or the expression of a physiognomy which at one time betrayed the petulance of a child, and at another the timidity of a young maiden, which gave so great a charm to her entire person? In honour of our visit, she had assumed a “toilette extraordinaire,” but I would rather have seen her in her usual costume, with the sling which she uses so adroitly thrown over her shoulder. Curious, that this oldest of instruments of war and the chase should still retain its position in this kingdom, and that the form of the Sardinian “Fionda” should be so identical with that which David used in his combat with Goliath!

We now began our tour of the grounds, which was an enterprise of some hours, of which the pleasure surpassed the fatigue; for the survey of this large estate, just brought into cultivation, and the judicious explanations of our guide, so eminent in everything he undertakes, were as interesting as they were instructive.

It was in the month of May, 1855, that Garibaldi landed for the first time in Caprera, which at that period might have been described as a mass of granite, clothed here and there with a thin crust of earth, which was in part so covered with loose stones, that it produced little beyond a few brambles and a scanty supply of aromatic plants; now, at the expiration of but two years and a half (when I was there) may be seen a fine house and garden, and a large space in cultivation, entirely surrounded by a “muro a secco,” a mode of building much resorted to in Tuscany and other small Italian States, with this difference, however, that whereas all which I had before seen were merely rough stones placed one on another, the wall around this domain, though equally without mortar, was built of blocks which had been squared and dressed by the tool. Garibaldi told me that he had done much of this work with his own hands, but that other necessary employments obliged him to give it up.

This enclosure comprehends within its limits a nursery of cypress and chesnut trees, figs and other fruit trees, and a garden of vegetables, vines, and even sugar canes. Everything flourishes under this magnificent sky and fertilizing sun. Pools of water, fed by natural springs, are distributed here and there, thus maintaining a sufficiency of moisture, which, united with the sun’s heat, quickens the development of vegetation.

Several kilns were burning into charcoal the roots of shrubs that had been cleared off the ground. But while every freshly ploughed slope, where so lately the bush and the stone had reigned supreme, promised a rich harvest, every now faint, now louder, bark of a dog, and every echoing shot, warned the poor birds on the berry-laden boughs that they could no longer enjoy their lives in safety.

If the survey of this young and promising possession afforded us so much gratification, the conversation that passed at dinner gave us no less pleasure. We spoke chiefly in Italian, but from time to time the General expressed himself in French, with that rare perfection so difficult to attain. His sonorous voice, full of power and sweetness, called to mind the dominant qualities of his character; and if his eloquent language was not seasoned with wit, it was always full of knowledge and enthusiasm, and such as is seldom to be met with in a man of action.

When a few years ago I read Hoffstetter’s Journal of the Campaign in Italy (“Hoffstetter’s Tagebuch aus Italien”), a work which gives a faithful picture of the events of 1849, and also contains many interesting particulars of the public and private life of Garibaldi, I was far from thinking of even the possibility of being the recipient of the hospitality of this eminent man, whose deeds then awoke all my sympathy. Our conversation turned naturally on the past. Acquainted as I was with the disastrous events which caused the death of his wife, I did not dare to pronounce her name, but the General himself led the way to it. It seemed to please him that all the occasions on which the Brazilian Amazon had displayed her courage and presence of mind were so fresh in my memory, and with the same animation which so often lighted up his countenance when his beloved country was his theme, he now spoke with tearful eye and tremulous voice of the heroine of Imbiturba, Morroda Barra, Caquari and Lages. But it was not alone of her heroic qualities that he spoke. The womanly virtues of the never-to-be-forgotten Anita, he recounted with proud acknowledgment. Her sacrifices as a wife and a mother, the excellence of her heart, and the affability of her manners, he scarcely knew how to praise enough, at the same time holding her up to his daughter as a pattern and example.

In the year 1849 I was witness of the enthusiasm which he raised when he hastened to the rescue of the Eternal City from a disgraceful yoke; and if that excited outbreak, those thundering “evvivas” found then an echo in my heart, the veneration which I now feel for the Liberator must of course be doubly intense and true. No elegant American cloak now hangs on his shoulders. No ostrich-feather flutters proudly from his helmet. No picturesque – clad Moor follows his charger. No devoted companions obey his nod! In plain and humble civil attire, with but two faithful friends to share the leisure of his rocky isle, the cultivation of a waste is the object of his industry, the education of two dear children his recreation!

But it is not desponding hopelessness, it is not petty irritation, that has placed him in voluntary exile and apparent oblivion. The same heroism, the same hope, the same love of country still fill his heart, and bright years will yet open upon his future life! But exactly because the purest motives impel him, the most honourable intentions are his incitement, he prefers rather to wait in self-denying patience, than to prostitute his abilities to the satisfaction of a lust for renown, or an ambitious self-love.

After dinner, as we prepared to leave the house again, the weather looked uncertain; a fresh breeze had sprung up which now collected the clouds into masses, and now again dispersed them; letting a ray of sunshine through their openings, to light up the picture before us. Several small horses were feeding quietly, and giving life to the green meadow; goats grouped themselves on the most acute peaks, and stood out in relief against the sky, remaining in perfect immobility till Teresa surprised them by a stone which whistled through the air from her sling, when they bounded down, scampered over the even ground, and disappeared.

Wishing to have a view of the whole panorama of the island, I undertook, under the guidance of Garibaldi’s two friends, the ascent of the Tejalone; but after climbing up for above an hour, we encountered some blocks of stone, almost inaccessible, and thickets of brambles quite impervious. The summit, which I thought so easily attainable, now appeared more distant every step we took, and I was obliged to renounce my project. The same path downwards was so much more difficult than before, that we were necessitated to choose another, by which we obtained a view of a different side of the island.

Although Caprera is five miles in length, and fifteen in circumference, and a large proportion of it capable of cultivation, there are at present but six proprietors – the General, Mr. C. of Maddalena, and four shepherds. The first is the only one who possesses a house; Mr. C. purposes building one; but the shepherds live in some of the natural caves among the rocks. I was conducted to the mouth of one of these grottos, and there we found Maestro Giulio and his sons, who had finished their sport, and were talking with a shepherd and some other huntsmen.

“Have you killed much to-day?” asked one of my companions.

“Only two boars,” was the reply. “The bad weather diminishes the ardour, and spoils the scent of the dogs.”

“And these boars, to whom do they belong?”

What!” cried I, “has the game proprietors here also? and how are the hunters to know whom it belongs to?”

“In this island, Madam, as in many parts of Sardinia and Corsica, the boars we hunt are but a race escaped from the domesticated swine; and as soon as a proprietor sees a wild sow with a litter by her side, he marks them in a particular way which lasts till their death, and thus they become his property.”

We continued in conversation on this curious subject till we reached the house, without thinking how late it was, although the twilight already gave us a warning to depart. The wind had much increased, and our brave host declared that he must take us back himself; and he and his son, and one of his friends, prepared themselves accordingly.

The waters of the Archipelago, at times as tranquil as a lake, were now much agitated. The wind whistled with fury, and made our light canoe fly before it over the frothing waves.

Menotti executed with rapidity and precision the directions of his father, and his friend and Captain D managed the sails. Fear was impossible when with such men as these, but still I will confess that I was not sorry when our keel grated on the shore. Mrs. C, who had been watching our rough passage from her window, came down to us and invited us into her house. A bottle of wine of her own growth was not a thing to be despised; we took leave of the General and his companions, who went off in their boat again. I know not what we should have done without Susini, who was punctual to his appointment, to guide us home.

It was one of those nights which the immortal poet of the “Inferno” calls “una povera notte,” and we were obliged to grope our way over an uneven road, along which we were sometimes driven on by the wind, and sometimes deluged by the rain, the squalls succeeding each other almost without cessation.

We had scarcely attained the half of our distance when we distinguished other footsteps than our own, and my ears were startled by hearing my own name pronounced in an unknown voice, and who should it be but Mr. C-, returning home, leading his horse by the bridle!

In spite of my desire to stop and speak to the eccentric inhabitant of the “Punta della Moneta,” we could in so terrible a night only exchange a word and an English shake of the hand, and even that was much for people so tired, and wetted, and blown to pieces as we were. At last after a two hours’ walk we reached our lodging once more.

I soon forgot my fatigues and the contrarieties of our nocturnal promenade, for before I had completed the exchange of my dripping garments for dry ones, a visit from Captain R was announced.

The conversation of such a man, so full of sense and imagination, charmed me the more as he expressed a lively interest in Italy and a love for the fine arts, which soon produced that sort of mutual understanding which always exists between persons of similar tastes. The intimacy of Captain R. with Byron and Shelley had left in his mind a store of precious recollections. He told me the details of the passion which Byron had conceived for the fair Guiccioli. He spoke of his enthusiasm in the cause of freedom, of his generous conduct towards the conspirators of the Romagna, where his name is still held in public veneration, for he knew how to excite admiration by his character as well as by his genius. He told me also of the profound melancholy which beset the great poet when he lost his daughter Allegra. Captain R. afterwards recounted with the liveliest emotion the death of his friend Shelley, accompanied as it was with some extraordinary circumstances.

“The evening before that sad event,” said he, “I was with Shelley and Byron at the fête which was given in their honour on board an English ship of war, then lying before Livorno. After the ball was over, Shelley, accompanied by one of his friends, Mr. Williams, wished to return to his villa, and departed in a small boat for Lerici, in the Gulf of La Spezia. General opinion attributed the accident to a tempest; but this cannot have been the case, for during the whole night in which Shelley was drowned the sky was clear and the sea calm. His boat must have been run down by some vessel, or struck on a sunken rock; which I think corroborated by the circumstance of my having found in the boat, after she had been raised from the bottom of the sea, a packet of silver plate which had been used at the fete in precisely the spot in which I had placed it.

The sad loss of our two countrymen reached us but too soon. I went at once with some friends to Viareggio, where the sea had washed the bodies ashore. We got there in time to render the last duties of friendship. Italian enmity against Protestants was then greater than it now is, and they would not suffer us to bury the bodies. We had no course left but to burn them. I shall never forget the desolation and solemnity of the aspect of this funeral ceremony,” said Captain R. with an emotion of which thirty-five years seemed to have scarcely diminished the first violence. After a pause, he thus continued: –

“We selected a spot near the shore, and close to one of those large crosses so frequently seen in Italy. Before it lay the Mediterranean Sea, dotted over with its beautiful islands. Behind it appeared the majestic chain of the Apennines. On the right and left were woods of pines, and underwoods of bushy plants, of which the ocean winds had bent and stunted the topmost branches. A perfect calm reigned over the waters. Little wavelets caressed the yellow sands, the colour of which contrasted finely with the sapphire blue of a sky almost oriental! The gigantic mountains showed sharply their snowy outlines in the pure atmosphere. In the centre of such a scene rose the bright flame which was reducing to ashes the bodies of our two friends. The smoke enveloped the cross for a moment, and then mounted high towards heaven, like a symbol of Christian faith and the immortality of the soul.

“The heart of the Poet had been removed, and was subsequently buried with his ashes in the Protestant cemetery at Rome.

“It was thus that England lost one of those men of genius who promised to add to her glories. Nobody denies Shelley’s great fault. It is difficult to defend him; but it should not be forgotten that after his marriage had conferred on him more happiness of mind, his irritation against mankind became less bitter. He had begun to rectify his opinions, and we may find in this some justification for a belief that had he lived longer, he would have completely abandoned his errors, and his genius would have shone forth without a blemish.”