THE ISLAND OF SARDINIA AND ITS PEOPLE

Traces of Many Civilizations to Be Found in the Speech, Customs, and Costumes of This Picturesque Land ⇒

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

by CLIFTON ADAMS ⇒

Staff Photographer, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE

THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE

Voul. XLIII, No. 1 – January, 1923

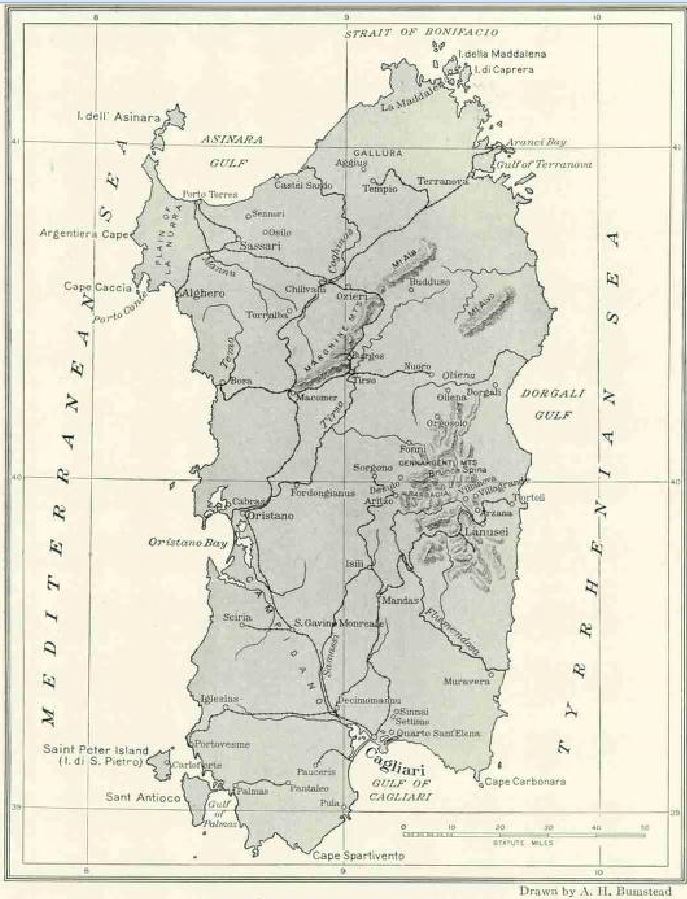

UB of the western Mediterranean is Sardinia. Along the trade route spokes which bind this rocky island to surrounding lands, a thousand diverse influences came to flavor the life and color the character of the Sardinians.

From the time when Phoenician ships found in Sardinia a counterpart of their home ports, where Lebanon comes down to meet the sea, the island west of the instep of the boot of Italy has been overrun by one race after another. Three continents have left their impress on the life and features of the people.

The island has lain open to influences from without. But the mountains, which almost monopolize the land, have so segregated the various parts that to this day each village has a flavor of its own. Sardinia is still unspoiled. The banditry of the open road has become a mere tradition and the most romantic islander is liable to prove a solicitous friend. Hotels are few and trains are leisurely. But so diverse, so interesting, is the life among the rounded hills and on the widespread Campidano that the traveler is well repaid for such discomforts as result from sharing the life of the people, whose hospitality with the little they have shames the greedy magnificence of famed resorts.

Poor though she be in worldly goods Sardinia is rich in welcome for those friends who come to visit her, try to understand, and willingly submit themselves to the same curious study that they give to the Sardinians in whose homes they live.

IRRIGATION AND AUTOMOBILES MAKE THEIR ADVENT IN SARDINIA

And let not the apostle of progress and standardized life be discouraged. European clothes are displacing the brilliant costumes for which Sardinia is rightly famous. Cagliari, citadel-crowned, now jangles with tram-cars which serve the lower town, with its steel-framed buildings beside wide thoroughfares. Automobiles are already disputing the roads with slow-paced oxcarts on crude wooden wheels. Irrigation works are under way. and soon the turbulent streams will be impounded in great inland lakes, with all the countryside enlivened by electricity, while vast regions are reclaimed for agriculture.

As yet, however, the story of travel need not mourn too much. In the inland regions, Sunday flames forth in scarlet glory from the somber garb of working days, and diminutive donkeys and patient oxen slowly plod the roads which Romans built when Rome was mistress of the world.

If the motor car does intrude amid bucolic solitude, it serves to carry one through charming scenes of rich diversity and thread upon a brief itinerary such smiling welcomes as que would travel far to see in larger and lands.

The greater portion of the island is covered with low mountain ranges, most of which have a round, smooth shape. The southeast regions have peaks of Alpine grandeur, but the highest mountain in the land the Gennargentu more imposing for its mass than for its altitude of 6,233 feet. Its summit, which commands a wonderfully extensive view, may be easily reached on horseback, although its loftiest peaks are snow-covered during much of the year.

“SARDINIA TURNS ITS BACK UPON ITALY”

Along the eastern coast of Sardinia runs a mountain chain which presents a brusque escarpment toward the mainland and makes the island difficult of access on this side. No safe natural harbor or well-sheltered bay is to be found between Cape Carbonara and Aranci Bay.

On the western side, the mountains have gentler declivities, and here are situated the most beautiful gulfs of all the island-the gulf of Palmas, so much spoken of by Admiral Nelson, and the Porto Conte near Alghero, a natural harbor capable of sheltering the most powerful fleet in the world.

The most extensive Sardinian plain is that which stretches northwest from Cagliari to Oristano. It produces on the traveler a strange impression. Although it is scarcely 50 miles in length, it appears immense, for it is proportioned to the scale of surrounding objects, especially to the modest height of the mountain ranges which limit it.

In spring this plain, the two parts of which are respectively named the Campidano of Oristano and the Campidano of Cagliari, is covered in its uncultivated tracts with the most beautiful wild flowers, which impart to the scenery a warm, variegated tint and greatly embellish the landscape.

During the summer months a pitiless sun with scorching rays dries and burns. everything, and the plain, covered as it is with a yellow, monotonous mantle of dried herbs, takes on a desolate appearance. The unpretentious villages, built of sun-baked bricks, acquire an aspect more miserable than before.

FIVE MONTHS OF THE YEAR WITHOUT RAIN

From June to the end of October no rain falls on the island. From week to week one cannot detect the slightest cloud in the blue sky, which in the hottest hours assumes a milky tint.

Two other plains, less extensive and interesting, lie in the upper part of the island – the Plain of Nurra in the north-east, which ends at Argentiera Cape, and the Campo of Ozieri, which lies near Chilivani, a junction point where four railway lines converge. Both have a somewhat different aspect from the Campidano.

With these exceptions, Sardinia, especially in its central part, is but a network of mountain ranges, an uninterrupted mass of round-topped, treeless hills, green and lovely in spring, yellowish brown and desolate in summer, although here and there, along the slopes of the Barbagia Mountains, patches of verdure are found, even in the hot season.

DEVELOPMENT DEPENDS ON FOUR RIVERS

Naturally one would expect many rivers in an island of many mountains; but in Sardinia this is not the case. Owing to the scarcity of rain during several months of the year, Sardinian streams hardly deserve the name of rivers. In winter, after drenching rains, they become true torrents and are rapid and dangerous in their course; in summer they dry up al- most completely, and a narrow rivulet of muddy water, which can easily be crossed at one step, is frequently all that remains of an impetuous winter torrent. Sometimes a four-arched iron bridge. spans a narrow ribbon of water between stretches of flints which mark the course of a wet-season river.

The four main rivers deserve a special note, because on their regulation depends the welfare and prosperity of the whole island.

The Tirso has its source in the granite table-land of Buddusò, in the upper part of the island, and after a course of 84 miles debouches at Oristano Bay, where in ancient times rose the Roman town of Tharros. The Flumendosa rises in the mountains of Barbagia and enters the Tyrrhenian Sea near Muravera, on Corallo Bay. The Coghinas, which has its source in the mountain ranges of the Marghine, in northwestern Sardinia, empties into the Asinara Gulf, and the Temo enters the sea near Bosa.

SARDINIA EXPECTS TO HAVE LARGEST ARTIFICIAL LAKE IN EUROPE

In the central part of the island an imposing dam, 235 feet high and 250 feet thick, has been constructed. It is de signed to retain and collect the waters of the Tirso in such a way as to form an artificial lake about 12 miles long and 40 miles in circumference, which will be the largest of its kind in Europe. Electric turbines will supply current throughout a large part of the island.

A special feature of the construction is that the turbines and the electric machinery are placed in the very body of the dam. The overflow is to be collected in a large reservoir near Fordongianus, and by means of three canals the water of the Tirso will be directed to flow through the plains which surround Oristano, watering an extensive tract of cultivable ground, to the great advantage of agriculture and improvement of health conditions. The turbines are already at work and electric current is being provided at a cheap price, both for lighting and industrial purposes.

The scenic features of the valley where such imposing works are being carried out will be quite changed, and in summer the plain near Oristano will not have the same appearance as now. When the artificial lake is formed, the rocky, barren flanks of the hills, now covered with wild shrubs, will be replaced by large tracts of cultivated, well-watered ground. Factories will rise where now there are only a few miserable huts, inhabited by poor shepherds who guide their flocks in search of scanty food.

The Flumendosa, though it has a shorter course than the Tirso, is certainly more impressive, both for the volume of the water it carries and the picturesqueness of its banks. It flows between barren hills, but during the summer its banks are covered with oleander shrubs. The landscape assumes a lovely appearance, and the pink flowers of the oleander mingle with the brown hillsides, while the river, which even in the hottest months retains a considerable volume of water, winds here and there, or spreads wide its flood, according to the conformation of its bed.

The landscape in this part of the island is typically Sardinian. Villages are situated far apart. Occasionally a flock of white sheep studs the side of a hill, where a small stone inclosure around a cone-shaped, thatch-roofed hut indicates the existence of a fold. The highroad, in splendid condition for motoring, in spite of innumerable curves and hairpin turns, runs along the side of overhanging hills, barren and white.

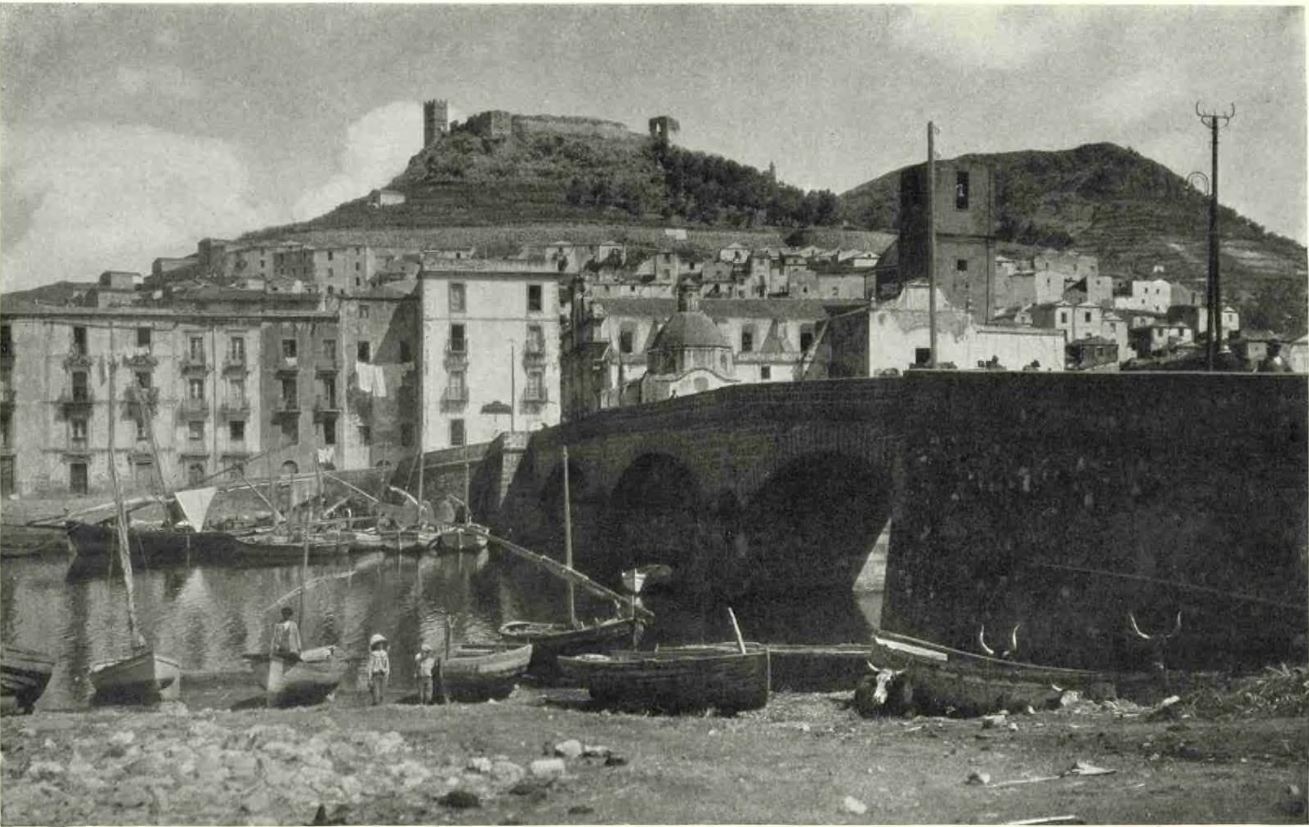

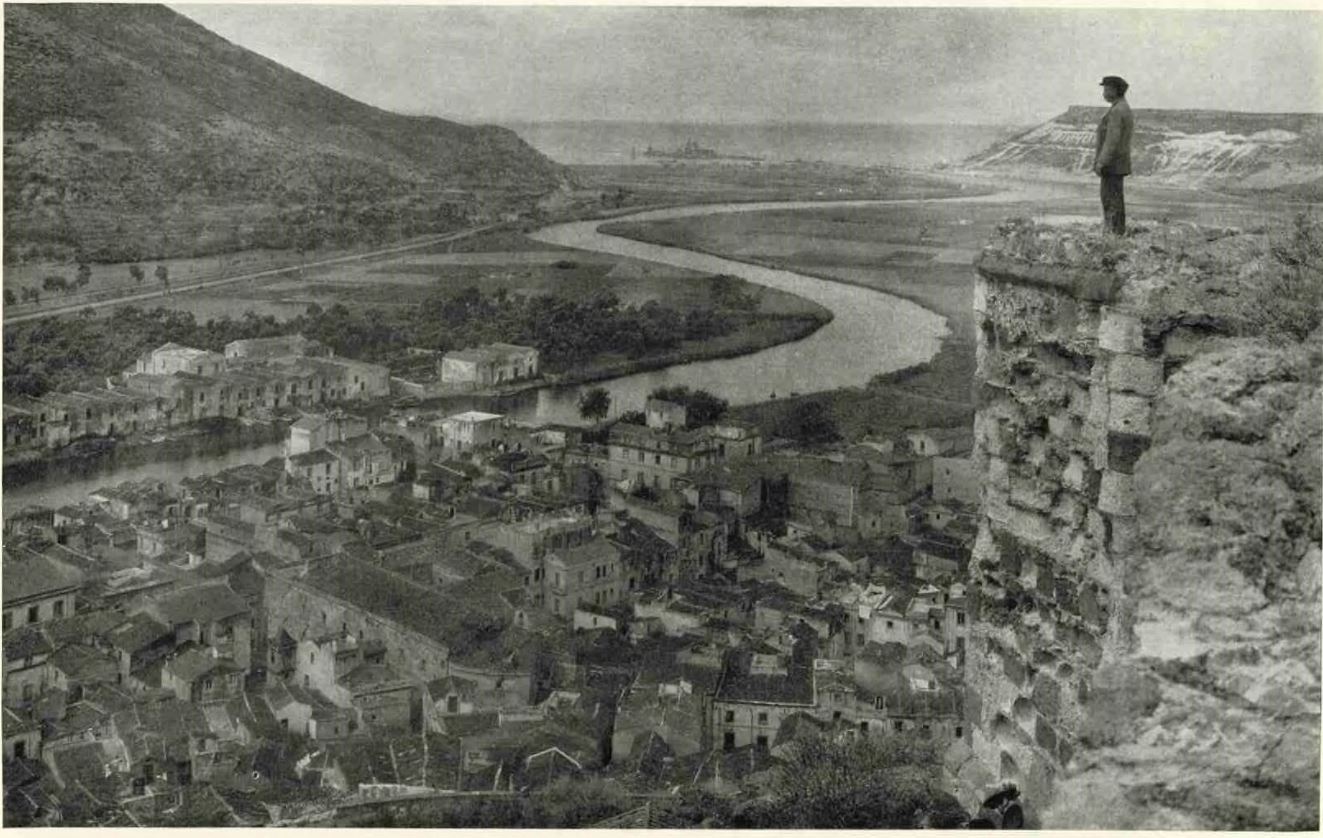

Another stream which enters the sea on the western coast is the Temo, on whose banks the town of Bosa is built. It looks more like a river than any other watercourse in Sardinia. Boats with widespread sails can ascend the current for alnost two miles, and near Bosa the river flows amid the most beautiful orchards and gardens in Sardinia; but its course is so short and the roadstead into which it empties so open that the Temo has no commercial importance.

The same firm which has planned and carried out the construction of the Tirso dam has been commissioned to build similar reservoirs for the Coghinas, Flumenda, and Temo rivers.

SEA POOLS A FEATURE OF THE SOUTHERN PROVINCE

Along the Sardinian coast, chiefly in the southern province, are considerable sheets of water, popularly known as stagni di mare (sea pools). Cagliari is surrounded by such pools, which, being in direct communication with the sea and retaining in their water a considerable amount of salt, are not dangerous to health, as the larve of mosquitoes can not live in them.

The lake of Santa Gilla near Cagliari forms a striking feature of the landscape and is the haunt of innumerable wild ducks and other waterfowl. Especially is it a favorite spot for the flamingoes that emigrate from Africa to spend the hottest months of the year in the neighborhood of Cagliari.

In August, a little after sunset, those strange birds may be seen flying high above the city, in their daily journey from the west pool to the east. Seen from below, they look like so many crosses, with their outstretched necks, trailing legs, and short wings.

THE MAIN ISLAND SURROUNDED BY ISLETS

The stern Sardinian coast, with its spurs and cliffs, presents an abrupt east- ern wall with few indentations. On the western side, the shore has a gentle slope. as far as the Gulf of Alghero and Porto Conte, the latter, however, being surrounded by high cliffs which form Cape Caccia, site of the famous Neptune Grotto. This is well worth visiting, but is difficult to enter, as its mouth is situated at sea-level and the slightest breeze piles waves against the entrance.

The main island is surrounded by small. isles, of which Sant’Antioco is the largest. A narrow tongue of land, with the aid of a short bridge built by the Romans, connects it with the mainland. Next comes the island of San Pietro, on which is Carloforte, center for the most important tunny fisheries in Sardinia,

Off the northeast corner there is a group of small islands, the most important being La Maddalena and Caprera. The latter is justly called the Sacred Island. Here lived and died the great Italian patriot Garibaldi, hero of two hemispheres. Many other unimportant islets are scattered around the Sardinian coast.

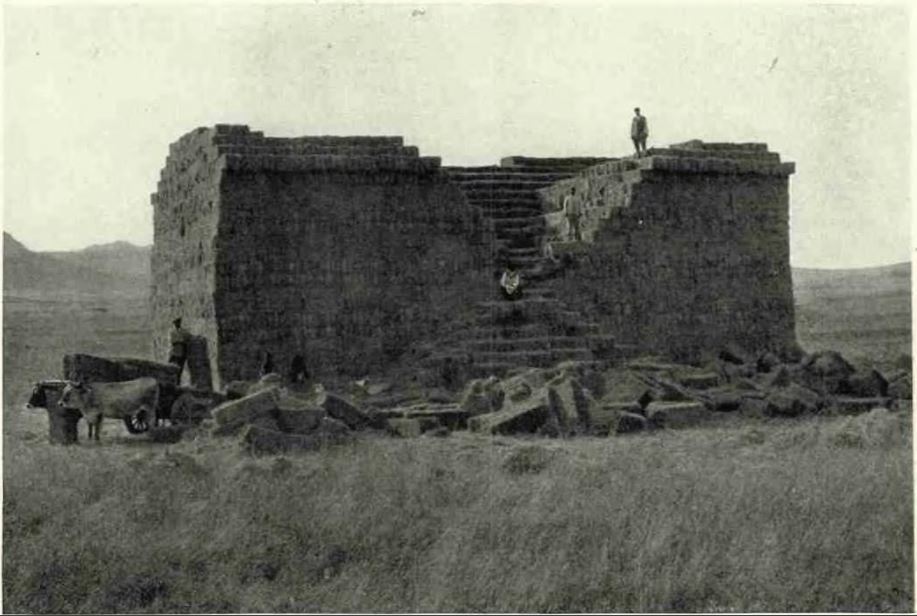

Sardinia is rich in prehistoric remains. No part of the island is entirely devoid of those quaint old monuments, which have defied time and weather and are still standing as evidences of an old civilization and a demonstration that the first Sardinians could not have been mere savages.

The traveler has always before his eyes these relics of the earliest ages, over which the cloudy wings of time have spread their shadow. These nuraghi are unmortared megalithic constructions shaped like truncated cones. After much controversy, archeologists have at last agreed that they probably served as fortresses, watchtowers, and even habitations for the tribal chiefs.

Many of these prehistoric structures, of which more than 3,000 are scattered throughout the island, are in an excellent state of preservation.

Nor should the visitor fail to see such other ancient ruins, dating from the bronze age, as the domus de gianas (witches’ houses) and sepolturas de gigantes (giants’ sepulchers), which are tombs excavated in the natural rock or temples to ancient deities.

Sardinia spreads wide its history book at the page which records man’s earliest existence. Treatises on Sardinian archeology are numerous and valuable, and whoever wishes to do so may study the subject thoroughly.

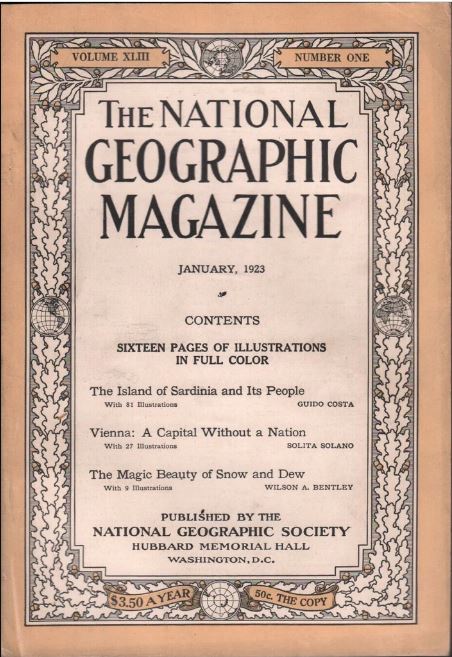

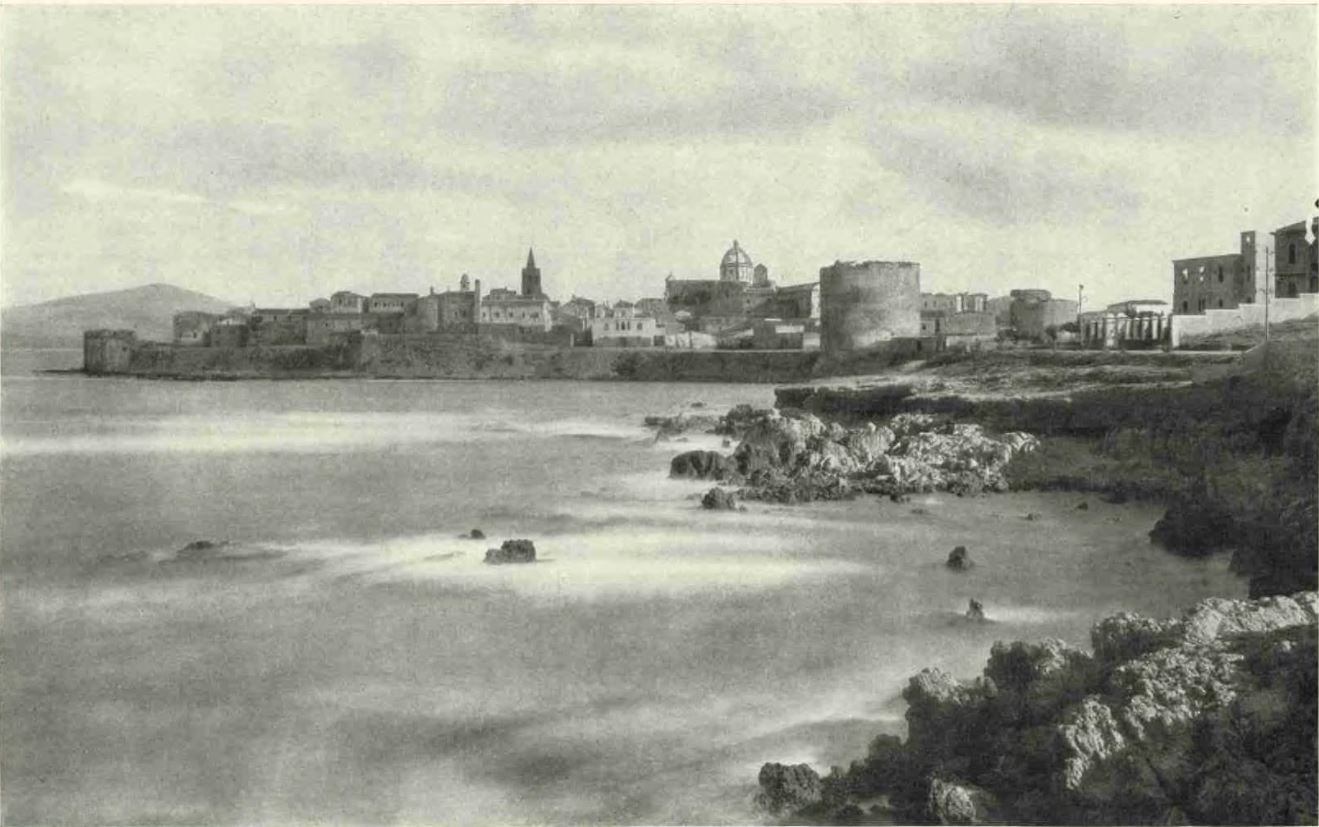

PANORAMA OF CAGLIARI FROM THE SEA

The largest port and most important city of Sardinia has a population of 70,000. Its wide Via Roma parallels the busy waterfront, and the new municipal building on the left is the finest in the island.

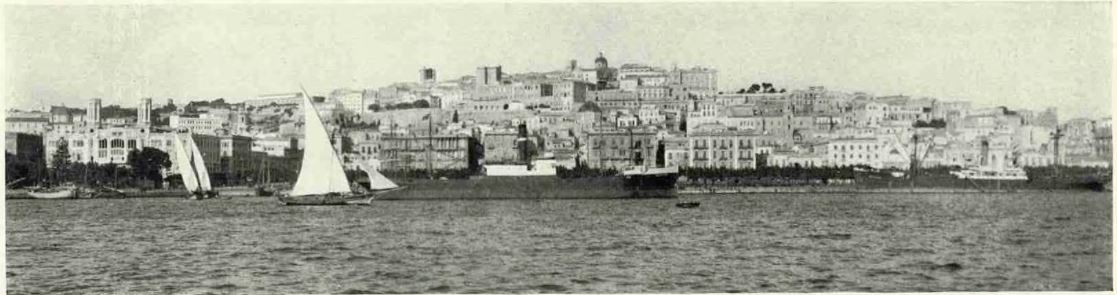

ITALY’S MOST IMPORTANT SALT WORKS, ON THE FLATS SOUTH OF CAGLIARI

Here the great piles of salt are liandied by steam shovels. The sale of this commodity is under control of the government and is combined with the sale of tobacco in the thousands of little shops throughout the kingdom.

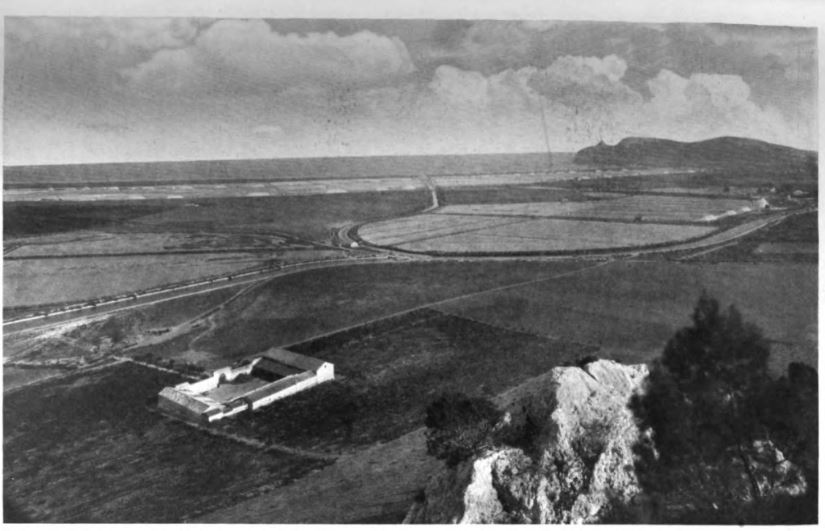

HANCIENT ROME HAS LEFT HER INDELIBLE, IMPRESS

The Roman occupation left interesting remains. Both in the Northern and the Southern Province there are relics of bridges, temples, and aqueducts, Cagliari can boast an amphitheater almost entirely excavated in the natural rock, where steps, corridors, passages, and dens for wild beasts are still to be seen. Called by the Romans Carales, this was in ancient times, as it is to-day, the principal town in the island.

Of such old Roman towns as Nora, Sulci, Olbia, and Tharros, all situated on the coast, only a few remains can now be traced, where solitude and silence reign. It is sad to wander among those relics of piers, temples, houses, and paved roads, so busy with life when Rome was the mistress of the world.

*See “Little-Known Sardinia,” by Helen Dunstan Wright, in the Nationa Geographic Magazine for August, 1916

To give an account of the medieval history of Sardinia, however short, would be a hard and useless task. The Sardinians themselves, incredible as it may seem, are as ignorant of their own history as any foreigner who comes to visit the island.

It is, however, convenient to convey a general idea of Sardinian history, as many existing conditions are explained by incidents in the past.

Such medieval monuments as Sardinia possesses are in complete ruin. Of the castles only a few moldering walls remain; so that any investigation concerning their shape, the disposition of their halls, or the splendor of their stately rooms is almost impossible. A ruin, a name, a legendary history of doubtful accuracy — these are all that remain of the castles which once held the summits of the Sardinian hills.

The age of Pisan domination was not a happy one for Sardinia, for never as in that period were the people so imposed upon and taxed; nevertheless, the island is indebted to that city tor its art. Many Pisan churches of exquisite Tuscan architecture are scattered throughout the island, but as they formed a part of monasteries and convents, they were built in spots remote from the main roads, so that those best preserved cannot be visited without some trouble.

WO SARDINIAN CASTLES FIGURE IN DANTE’S EPIC

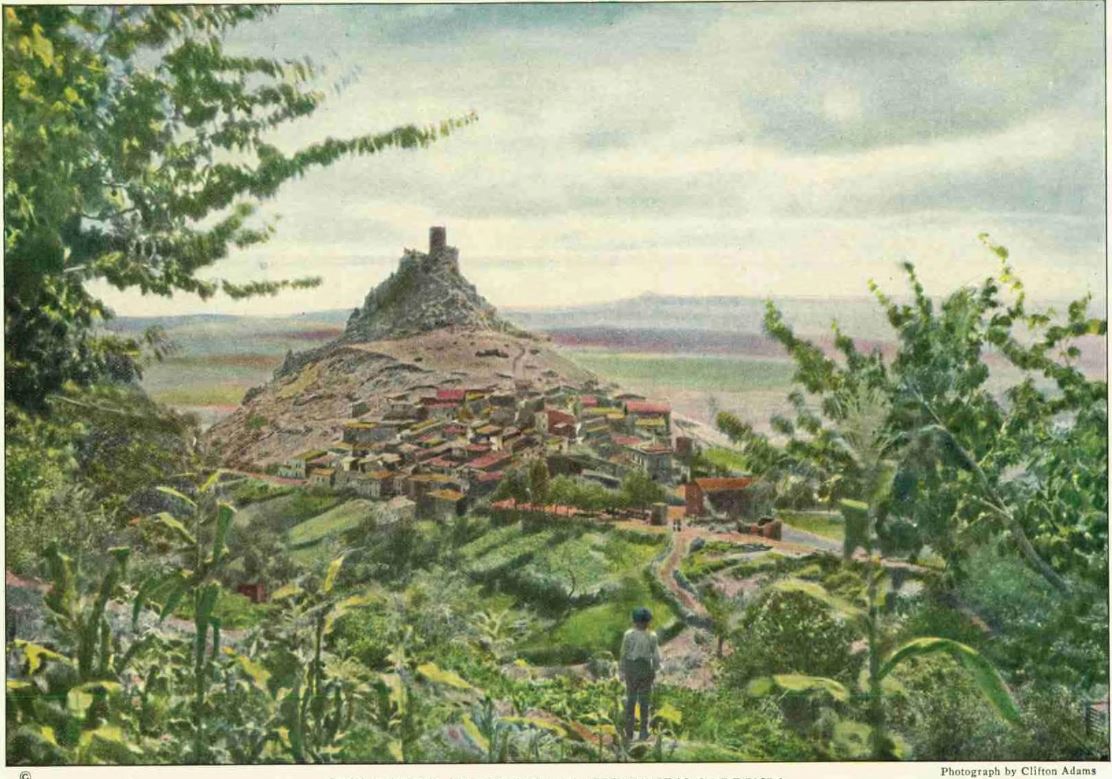

Two castles built in the Middle Ages are worthy of mention, both for their historical importance and because the names of their owners are recorded in Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

The first is the Castle of Goceano, known also as Castello di Burgos, a name taken from the village which lies at its foot (see Color Plate VI). It was built in 1127 by Gonario, one of the giudici of Logudoro, and there lived and died the unhappy Queen Adelasia of Torres, wife of Enzio, a natural son of Frederic II. This Sardinian queen also seems to have had some connection with that Michele Zanche whom Dante pictures in the depth of his Inferno, among the barattieri (cheats). The castle stands in a very picturesque position and commands a splendid view of the whole district known as the Goceano.

The other castle, situated near Iglesias, was called Aqua Fredda (cold water) and belonged to the powerful Pisan family of the Counts of Gherardesca, of whom Count Ugolino was one of the most important members. Those acquainted with the “Divine Comedy” will recall the celebrated canto of the Inferno where Dante gives a thrilling description of the death of Count Ugolino, doomed to die of hunger with his sons and nephews in the famous tower of Pisa.

Other castles, such as that of Malaspina, erected on the hill overhanging Bosa, and Castle Doria, in the Northern Province, are in a state of utter neglect and desolation, though they still afford precious material for the historical and sensational novelist.

HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE AGES IS CLOUDY

The Vandal invasions, the destruction of the monasteries, the neglect of ancient monuments, the lack of books and parchments, the many conflagrations which destroyed archive and sacristy, the mania of Sardinian peasants for digging and destroying every ancient monument in the hope of finding hidden treasure — all make the history of Sardinia in the Middle Ages rather a cloudy one.

With the exception of Cagliari, whose Castello, with its preserved towers, entrance gates, ramparts, and fort, retains even in modern times many traces of medieval life, the towns and villages in Sardinia have scarcely a monument worth mentioning.

The history of Sardinia might be summed up in a few words. Invaders in every age came to pillage, to carry away treasure, and to impose heavy taxes on the inhabitants, who had to fight incessantly lest they be torn to pieces by these birds of prey.

Then Sardinia had to endure Spanish rule, which brought misfortune to the whole island. Even at present many prejudices, hypocrisies, and false standards for judging life are but lingering traces of those Spanish rulers who carried away all the treasure they could, but left as a sad souvenir of their sway the worst traits of their character.

The Sardinian historian, Enrico Costa, has written a sonnet entitled “The History of Sardinia.” It gives a better idea of Sardinian history than many textbooks on the subject. Here is a literal translation:

Pheenicians and Greeks and Africans made her their prey and built the Nuraghi.

Carthaginians tried to make the most of her and the Romans contented themselves to keep her in slavery.

Then the Vandals, the Greek emperors, and the Moors worked her complete ruin.

Under the Pisans she had monks and lords, but Genoa, the usurer, treated her as a vile servant.

The Aragon dynasty gave her feuds, Spain kindled petty jealousies and asked for gold.

Piedmont appreciated the trick and ruled over her between altar and gibbet.

She was French and German, now she is Italian, but if God does not save her, no one knows what she will become.

The last verses of Mr. Costa’s sonnet sound rather too bitter. The author wrote them several years ago, when the Italian Government almost completely neglected the island and when political offenders were sent to Sardinia as a penal colony.

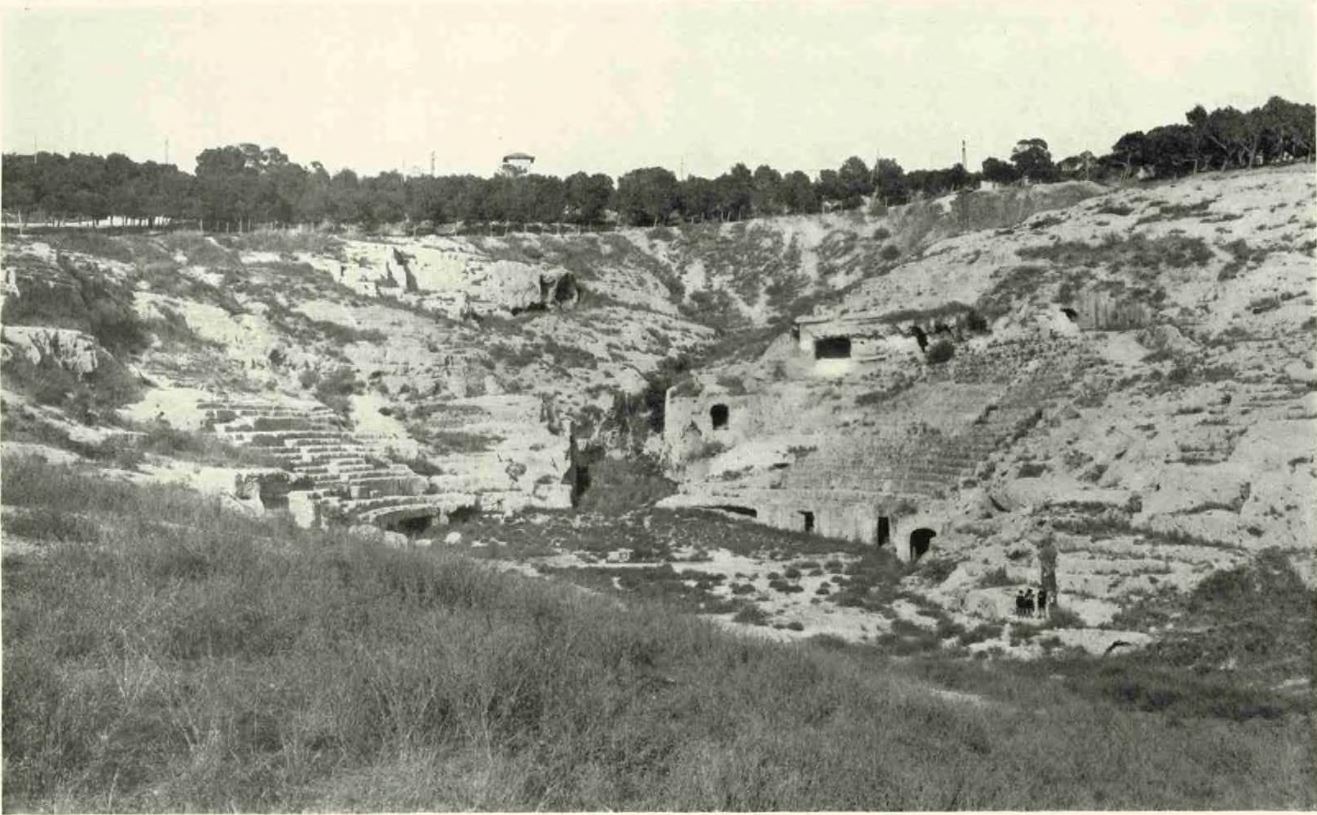

THE ROMAN AMPHITHEATER ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF CAGLIARI

Greek plays, audience sitting, as did the Romans, on the rock-hewn seats and on stones scattered over the This theater is sometimes used to state phoss the seats are passageways for the actors.

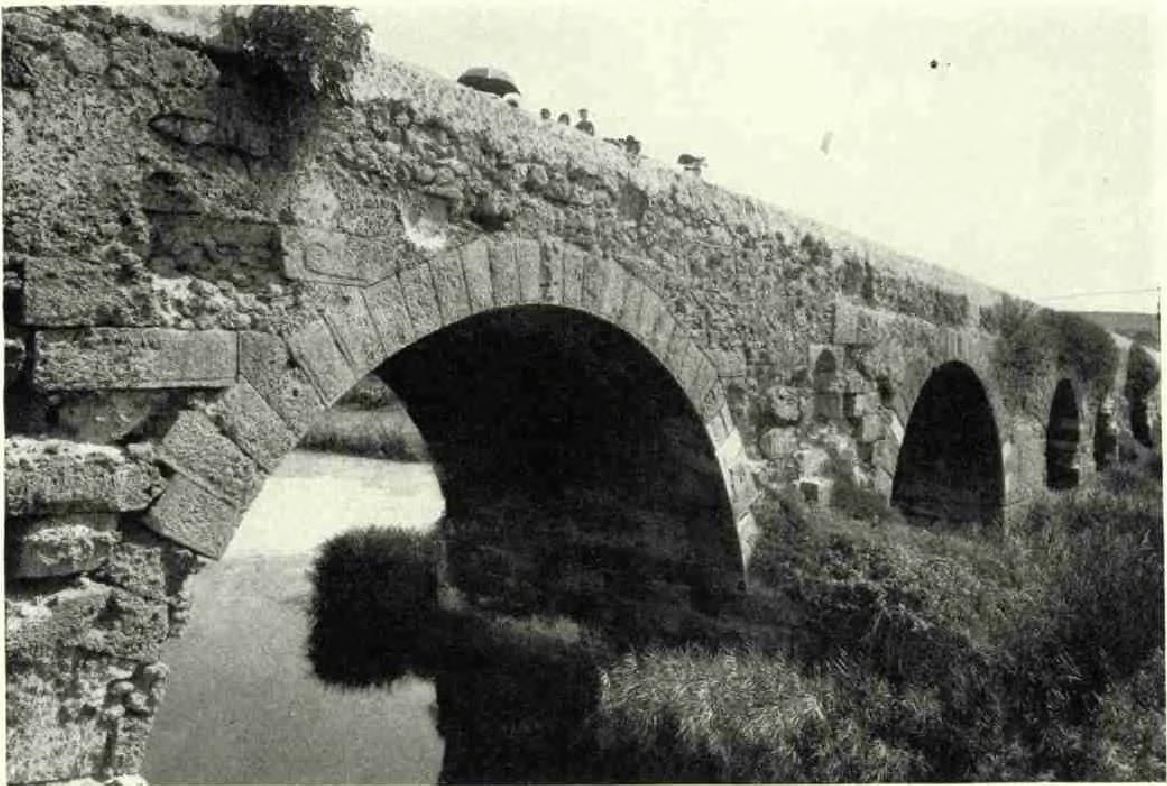

THE ANCIENT PONTE ROMANO OVER THE OTTAVA AT PORTO TORRES

Its seven arches of unequal span are constructed of huge blocks of stone.

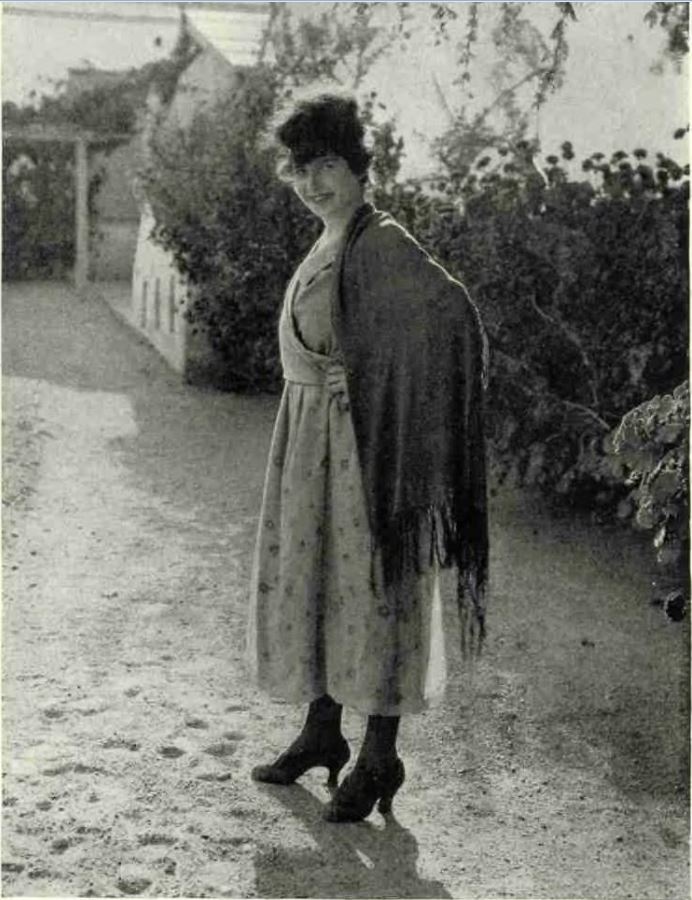

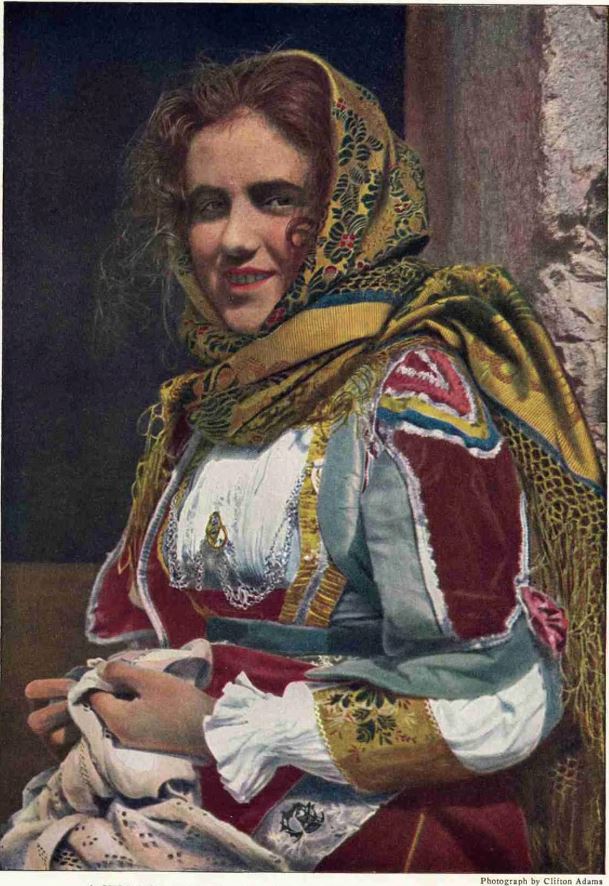

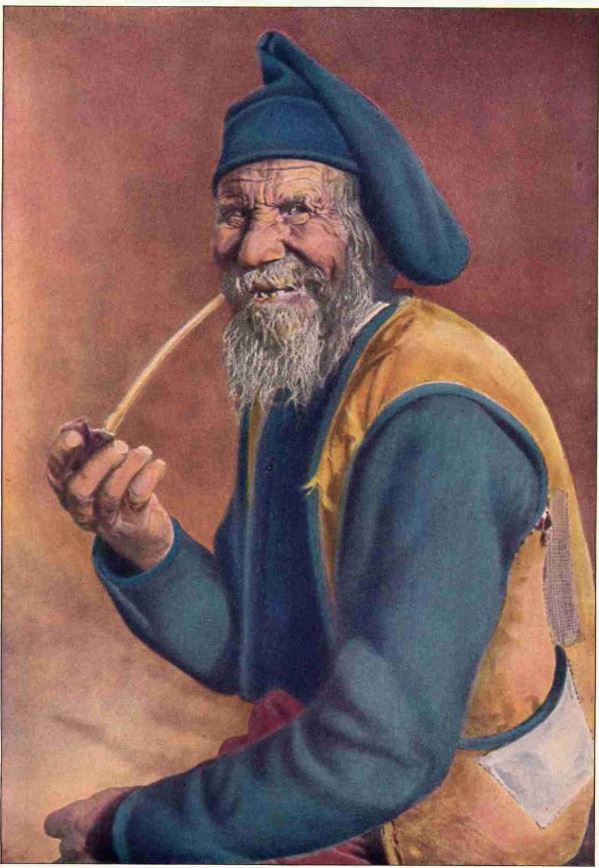

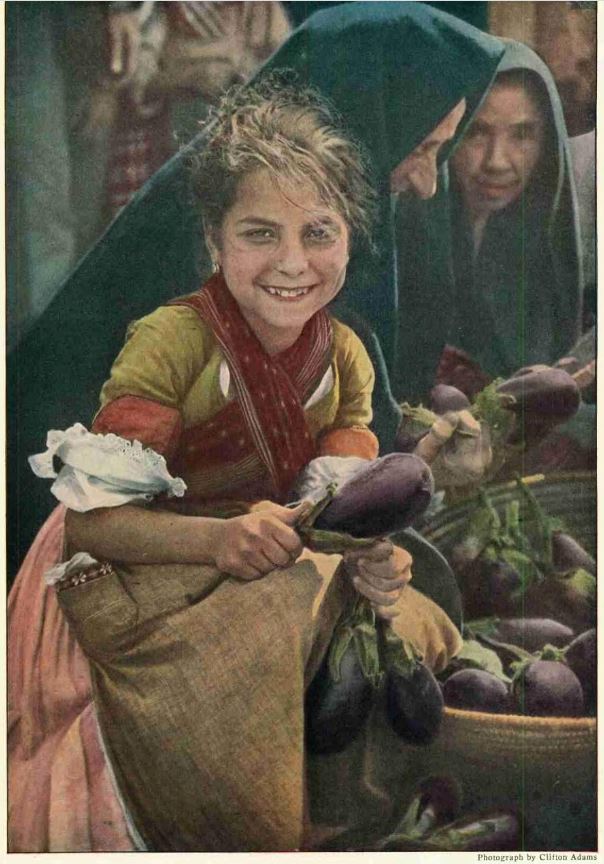

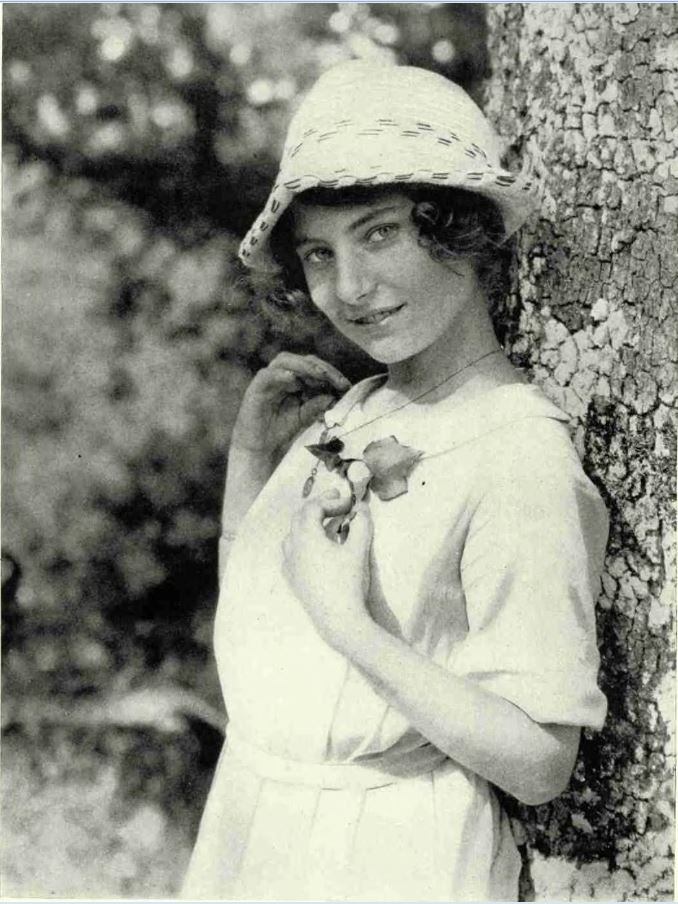

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

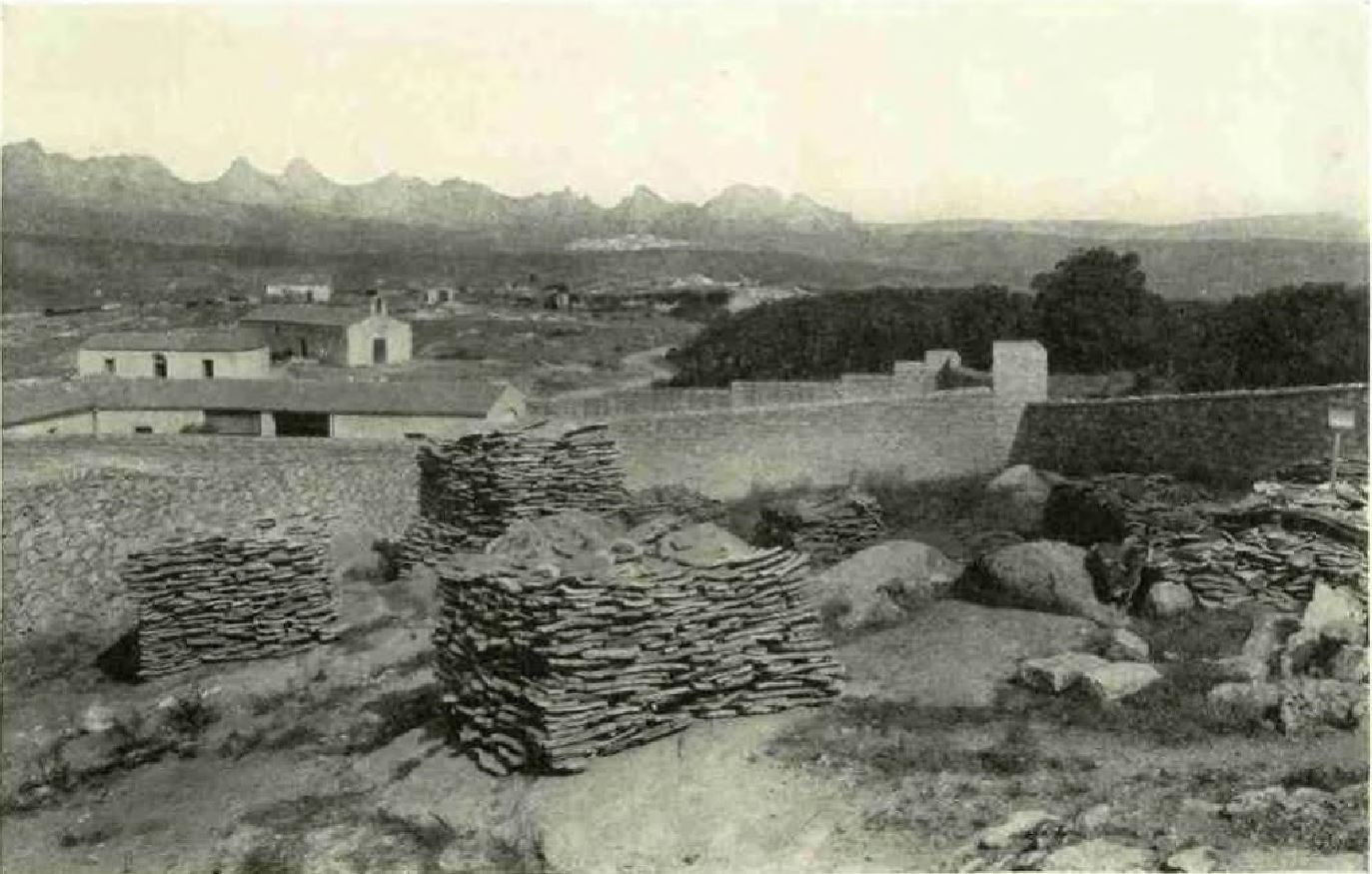

THE CASTLE OF BURGOS IN NORTHERN SARDINIA

The village of Burgos is in a picturesque spot below the ruins of a twelfth-century castle built on the granite peak of a detached hill overlooking the Tirso valley. The original Spanish colony consisted of only twenty-five families, but some of their customs have persisted to the present day.

FISHING BOATS COME UP THE OLD CHANNEL DUG FROM BOSA TO THE SEA

The old castle of Malaspina looks down on the town from the summit of an adjacent hill.

A PANORAMA OF BOSA FROM THE RUINS OF THE ELEVENTH CENTURY CASTLE OF SARRAVALLE

The view includes the new city and the ancient canal dug by the adventurers from Carthage who first settled here. The seaport is situated on the river Temo a mile and a quarter from its mouth.

Sardinia will always be Italian. Her sons have a strong attachment for their motherland, and Italy in turn owes much to the Sardinians for what they did during the World War. No soldiers proved more faithful and brave.

In this connection, it is appropriate to record that Sardinia will never forget what the American Red Cross has done for her children. This great organization has taught us to train our young people as Americans train their own.

SARDINIA HAS HER CAMP-FIRE GIRLS AND GIRL SCOUTS

These two organizations in Cagliari are under the instruction of women physical directors of the public-school system.

VARIETY IN MANNERS AND COSTUMES

In Sardinia, which is so small in comparison with the countries by which it is surrounded, an intelligent visitor is at once impressed by the variety of scenery within a limited field. He notes, too, a difference in manners and habits between the inhabitants of neighboring districts and his ears soon detect the different dialects spoken in the villages through which he passes. The infinite variety of manners, speech, and costumes enhances the pleasure of his tour.

In reply to a letter from the Italian poet D’Annunzio, asking for some colloquial expressions in Sardinian dialect which he wanted to put into the mouth of one of the characters of his comedy, “Pit che l’Amore” (More Than Love), Enrico Costa replied:

“Your faithful Sardinian servant, who is very affectionate toward his master, begs leave to point out that it is erroneously believed by the people of continental Italy, and often by the islanders themselves, that Sardinia has but one aspect. It is not so. Sardinia may be divided into zones, and from zone to zone there is a great change of scenery, habits, customs, language, and expressions. Tell me, then, if you please, in what part of Sardinia you want your servant to be born?”

Five years later J. E. Crawford Flitch wrote, “Sardinia is as surprising in its physical as in its racial contrasts.” He makes a comparison between the highlands of Nuoro, which he calls the Switzerland of Sardinia, and the low, marshy lands of Oristano, – which suggest to him Holland; yet from one district to the other is but a few hours in what he calls “toy trains.”

One cannot too strongly stress the diversity within an island only 160 miles long and 70 miles broad. So, instead of giving a systematic description of Sardinia from north to south, or from east to west, it will be much better to treat separately such regions as present the greatest contrasts. It will be easy for any reader to trace them on a map.

A BIT OF OLD SPAIN IS TRANSPLANTED IN SARDINIA

If one visits Alghero and has previously traveled in Catalonia, he is at once struck by the resemblance between this Sardinian town and various places in Spain. In fact, Alghero cannot be called a Sardinian town. It is a colony from ancient Catalonia, and has kept unchanged the character of its early Spanish settlers. The very appearance of the streets, with their four-storied houses; the men, with their faces neatly shaven, who suggest some Spanish matador; the language, which is almost pure Catalonian — all make Alghero seem actually “foreign” to such a place, for example, as Villanova, with its gorgeously costumed women, situated only a few miles away.

Sassari, the capital of the Northern Province, is surrounded by olive groves whose stretches of gray-leaved trees are now and then broken by vast vineyards. The white limestone rocks are very soit and the country roads, incredibly dusty, have a whiteness which dazzles the eyes. The town itself is not so peculiar, but its inhabitants have a character which differs greatly from that of the other islanders. The Sassarese is talkative, gay, sociable, and hospitable, with a bit of humor tingeing every subject he discusses.

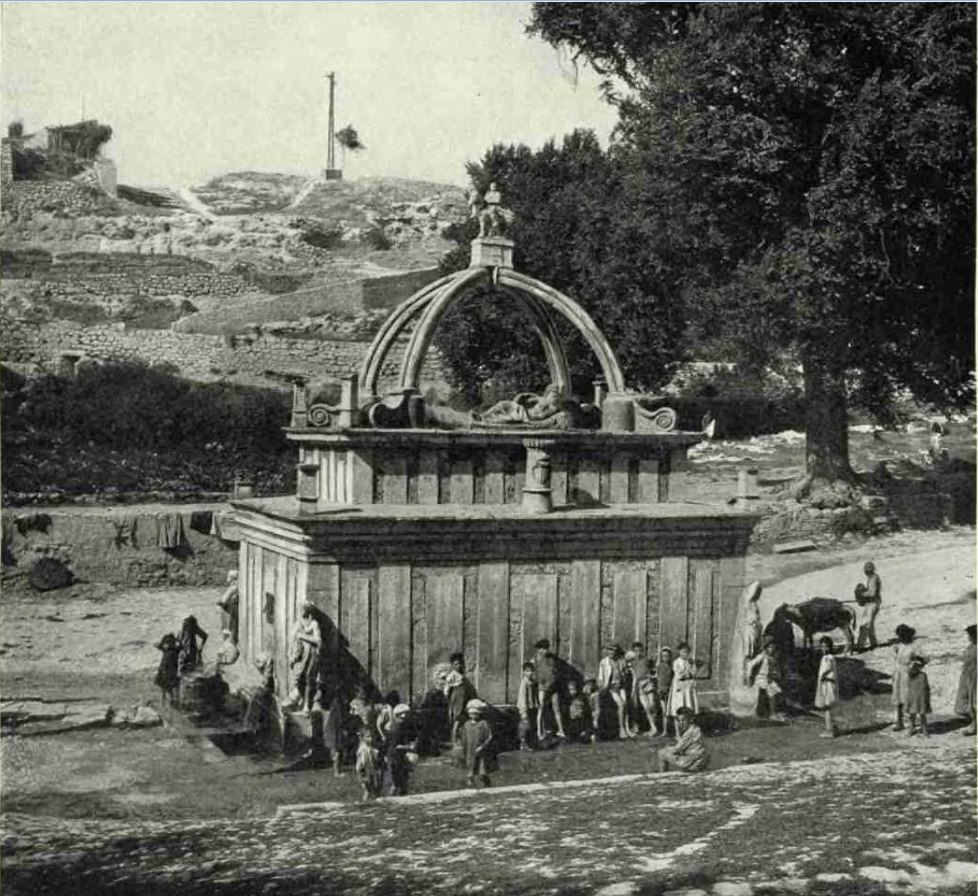

No writer, ancient or modern, has ever failed to speak of the Fountain of Rosello, It is curious to note how authors of different ages have invariably reported what was said about that modest monument by previous visitors; so that a legend has arisen about the extreme beauty of a fountain which possesses little. In 1849 an English writer said: “Few cities can boast a handsomer fountain than Rosello.” In 1885 another English writer printed the same words, and the quaint old monument, so modest in its dimensions and so plain in its ornaments, having nothing but historical interest, is favorably compared with the splendid fountains in which the Italian cities are so rich. The legend is, however, so strongly rooted that not to speak of the fountain of Rosello when describing Sassari would he considered a serious fault. Sassari may he called one of the foreign towns of the island, such as La Maddalena, Carloforte, and Alghero. It was a Pisan colony and the dialect spoken there still retains some ‘Tuscan characteristics.

La Maddalena is a Corsican colony and life is conducted there in accordance with the customs and habits of the motherland. The language spoken is almost a pure Corsican dialect, mingled with some Genoese words; but the visitor must be extremely careful in judging racial characteristics, for in La Maddalena live many Italian families.

Carloforte, which has taken its name from King Charles Emanuel III, is a pure Genoese colony. The isle of San Pietro, on which the town is situated, was given to the inhabitants by King Charles when he ransomed them from slavery. In former days the people inhabited the isle of Tabarca, off the Tunisian coast, and through an incursion of pirates all its inhabitants were made and sold at the slave market in That small, clean, lovely town is making successful efforts to thrive and improve, but being a smaller island, unconnected with Sardinia, its isolation is doubled.

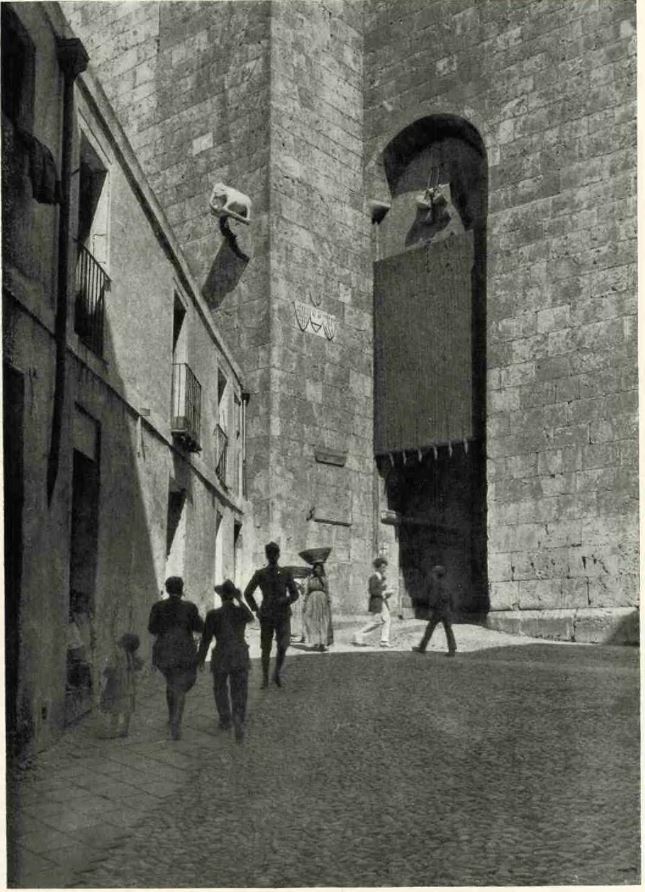

THE SOUTHERN SIDE OF THE PORT OF ALGHERO

After its evacuation by the Catalonians this city flourished under the rule of the Pisans, who fortified it with a wall and many watch towers, some of which are visible to-day.

THE WATER-SUPPLY SYSTEM OF SASSARI

At the foot of a hill below the market, in the eastern section of Sassari, is the ever-flowing Fontana Del Rosello, the water of which is carried up to the city in barrels on the backs of donkeys. The baroque fountain dates from 1605 and is crowned by an equestrian statue of St. Gavinus, tutelary saint of the north part of the island, who is said to have been a Roman centurion before his conversion to Christianity.

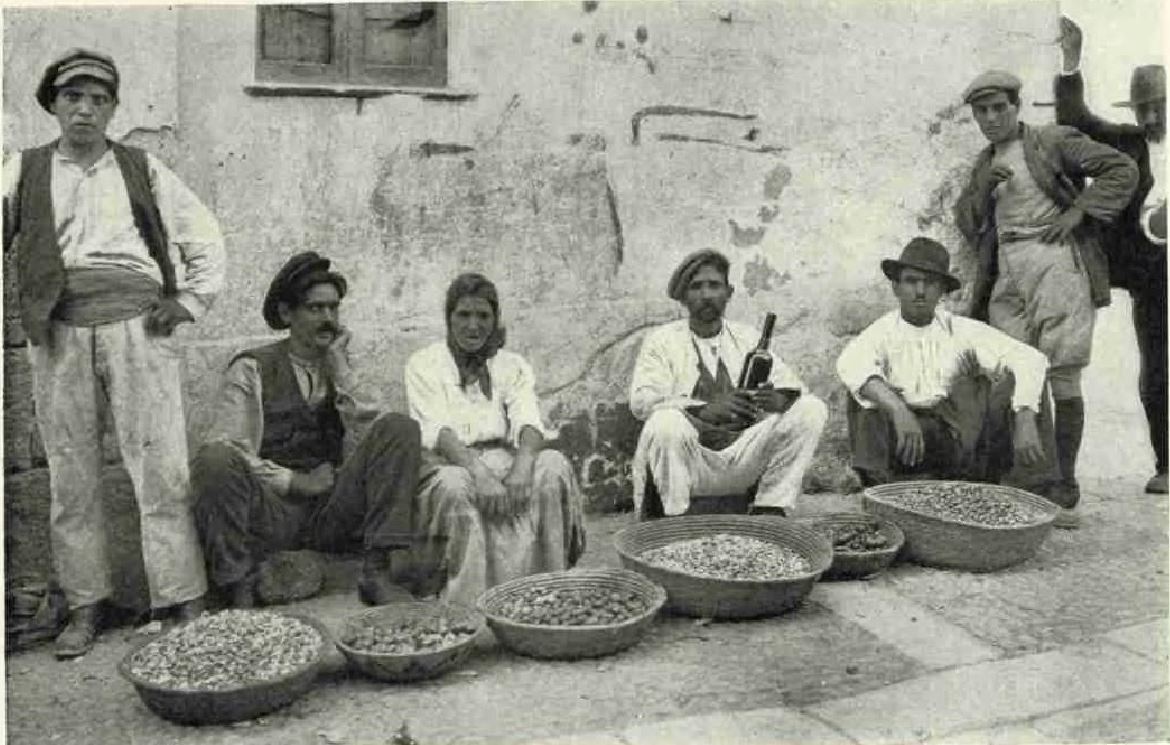

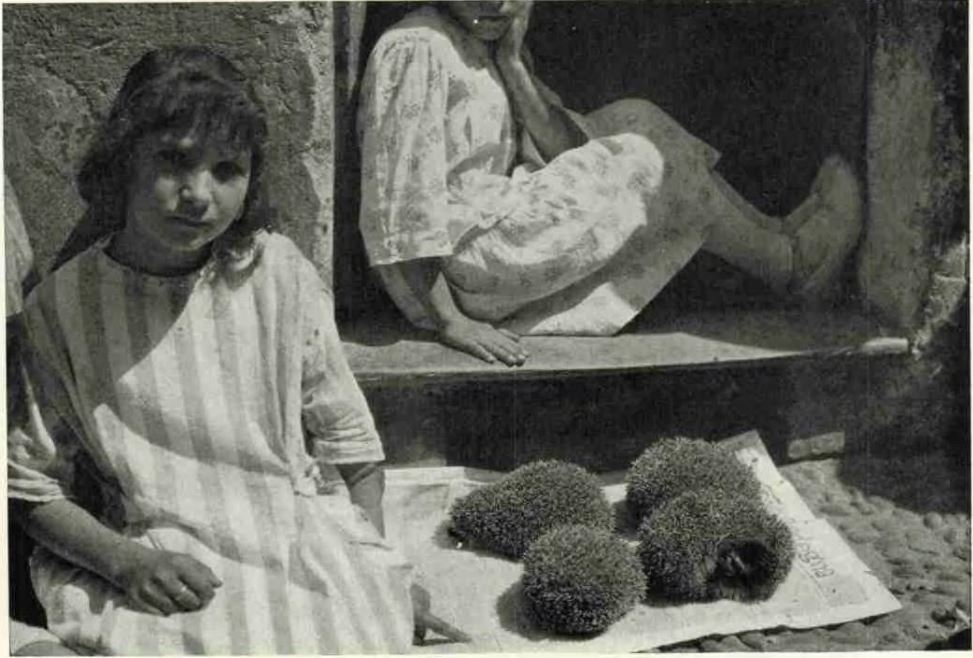

SNAILS FOR SALE

There are many varieties of small snails offered in the market place of Sassari. The Sardinians, like the French, prize them as a delicacy.

FAMOUS NOVELIST DEPICTS ONLY ONE PHASE OF SARDINIAN LIFE

The Sardinian novelist, Mrs. Grazia Deledda, has through her stories made the island known to Italians and to such other readers as have had the fortune to read them, but she has pictured only one phase of Sardinian life.

The description which she gives of that part of Sardinia where her heroes and heroines live is not inaccurate, but her works have had a deleterious influence on the estimate formed by people generally concerning the island. The part of Sardinia pictured in Mrs. Deledda’s descriptions is a small region, which, however interesting and characteristic it may be, is extremely circumscribed.

On the green plains of the Campidano, which surround Cagliari like an ample lawn, are large villages which are sure to interest the tourist or artist in search of the picturesque.

ROADS ARE HEDGED WITH CACTI

The Campidano villages are approached by long, dusty, sunburnt roads, widespread between hedges of the prickly pear cactus, with its purplish edible fruits, so common on the Mediterranean shores. The fleshy stems bristling with spines, which in the southern variety are long and stiff, are so tightly interwoven that trespassing is quite impossible.

During August and September women are often seen near these hedges, gathering the ripe fruit, which is fed to pigs. They use a long reed, which has been split at the top so as to form a kind of funnel that serves to clutch the fruit, tear it away and throw it on the ground. When a certain number of pears are thus plucked, another woman with a broom brushes off the microscopic prickles, after which the fruit is put into a basket.

GATHERING THE FRUIT OF THORN-PROTECTED CACTI

In the summer time women and children gather the sweet fruit of the “Indian fig” with long bamboo poles. An Italian syndicate proposes to erect a factory in southern Sardinia to make commercial alcohol from this fruit, which is rich in sugar.

TRANSPORTING BAMBOO MATS

These mats are made of the split poles of bamboo, which grows throughout the island in the low places. The peasants use the mats as coverings for carts, and in the home the cylinders serve as containers for storing grain.

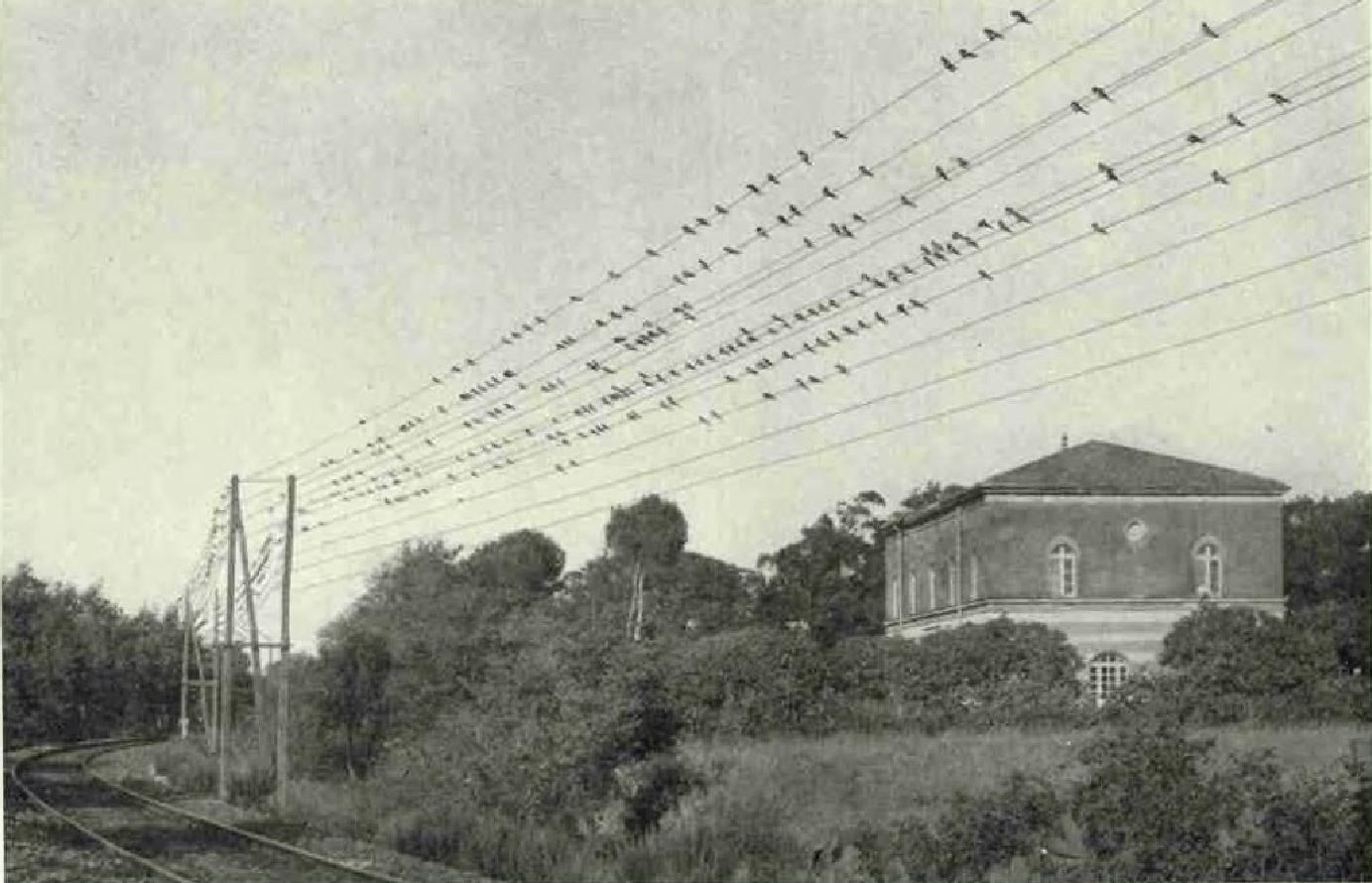

ON THE LINE IN SARDINIA

Countless numbers of white-breasted swallows build their nests under the eaves and window ledges of the rock houses in the hill towns of the island. This flock of feathered speedsters is resting from a frolic in the sky.

Sometimes the plain extends monotonous and uninterrupted for miles and miles and the villages, whose houses are invariably built of sun-baked bricks, almost disappear amid brown furrowed fields.

The village streets are broad and sunny, but frequently in the yery middle of the thoroughfare is a puddle of muddy water, which disappears dhly in the hottest months of the year. Now and then newly built houses with whitewashed walls and some pretensions to architecture, form a strong contrast to these long streets bounded by high, bare walls.

At short distances the flanking walls are interrupted by arched gateways, with large doors which have in the lower part two apertures, like those we often see in the lofty entrance doors of convents. This entrance is called in the Campidano dialect su portali.

These doorways constitute one of the characteristic features of a Campidano village, and the traveler is quick to notice them, as well as the almost complete absence of windows, which makes the street look solitary and gloomy.

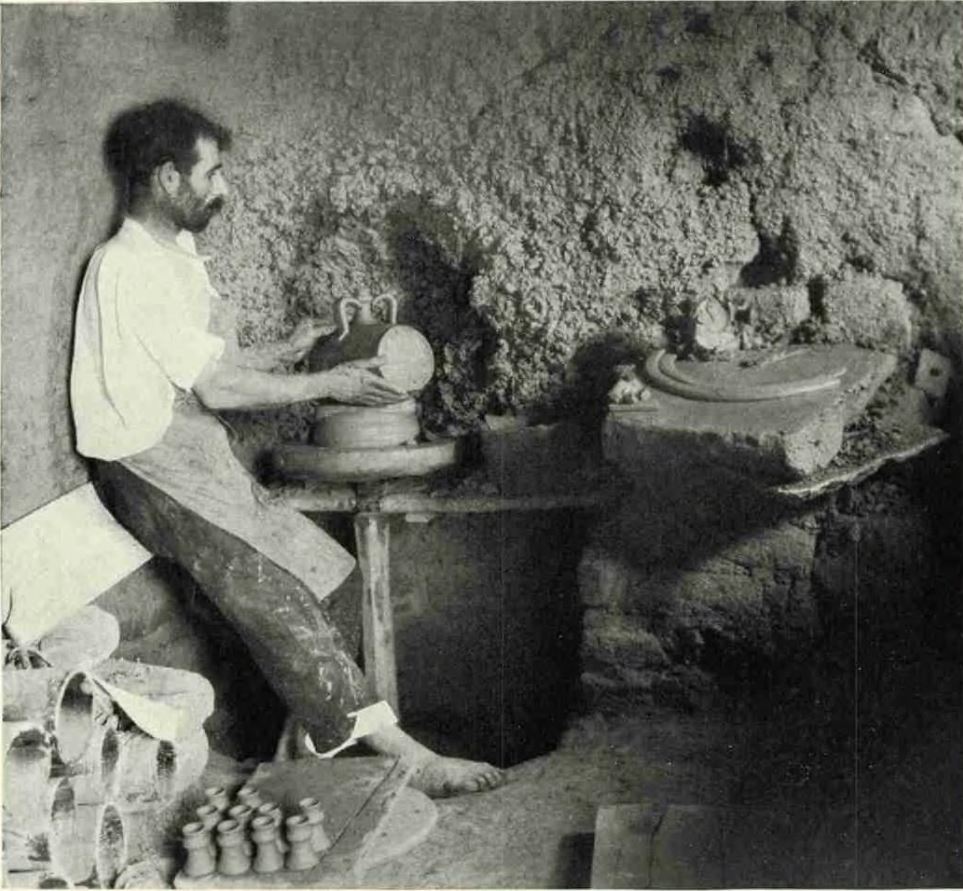

In an open space, usually on the out-skirts of a village, is the noria, on a circular stone platform, where a patient, blindfolded ass goes round and round, yoked to the wooden bar which turns the water wheel. Earthenware buckets are attached to a rope belt which revolves around its rim. The buckets, which go down into a cistern or well, overturn as soon as they reach the top of the device, pouring the water into a trough, whence it is led to a large reservoir to be used when the garden needs watering.

This device, so frequently found in Spain, is called by the Campidano villagers sw mudinu (the mill).

There is something oriental in the disposition of the village houses, streets, and gardens. From behind the high walls which shut in the streets, one often sees the waving tops of luxuriant palms, which suggest enchanting gardens and hidden flower-beds. This suggestion of concealed beauty is strengthened if the passenger catches glimpses of the inside of the compound through the small door in the portali when it happens to be ajar.

THE “LOLLA” Is THE PRIDE OF THE CAMPIDANO HOUSEWIFE

On passing the threshold, one finds himself in an ample courtyard, which in most houses is divided into two parts. On the western side, where the sun shines nearly all day, is a kind of veranda, upon which open the doors of the various rooms of the house. The veranda is decked with most beautiful flowers, cultivated in earthen pots.

In front of the veranda is usually a small garden, where oranges, palms, and a variety of fruitbearing trees grow luxuriantly. This porch, or veranda, is called sa lolla.

The lolla, with the open space in front, is a modification of the Spanish patio, and the same name is used in the dialect of the Northern Province to indicate the open space before a country house. The lolla is the pride of every Campidano housewife, whose passion it is that everything shall be neat and beautiful.

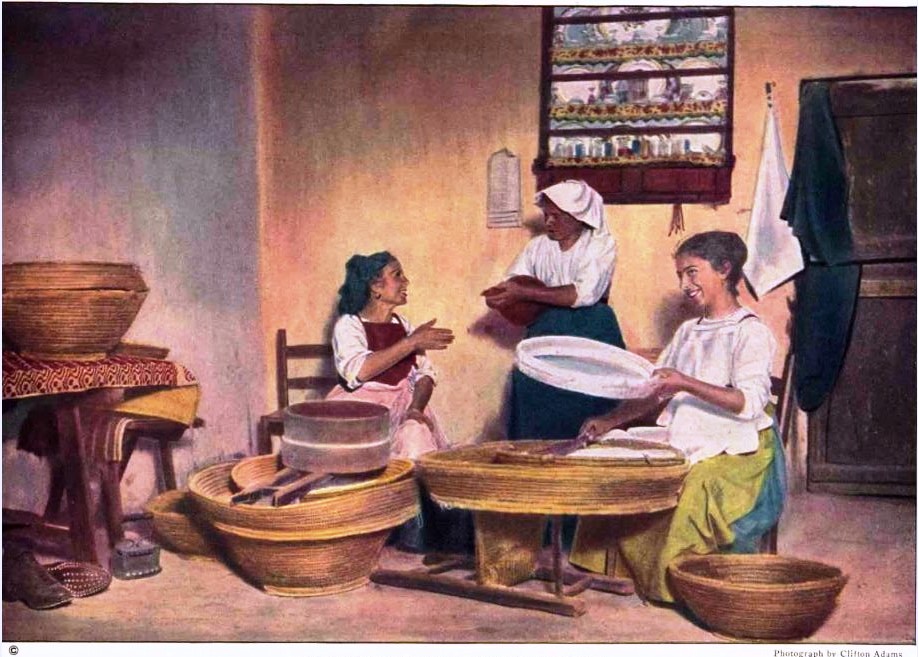

In a small room is the millstone, for every household has its own gristmill, turned by a patient little ass which is blindfolded to prevent dizziness. The inclosure is so small that there is scarcely enough room for the maidservant to watch the industrious animal and inspire him with a short rod when he stops (see illustration, page 22).

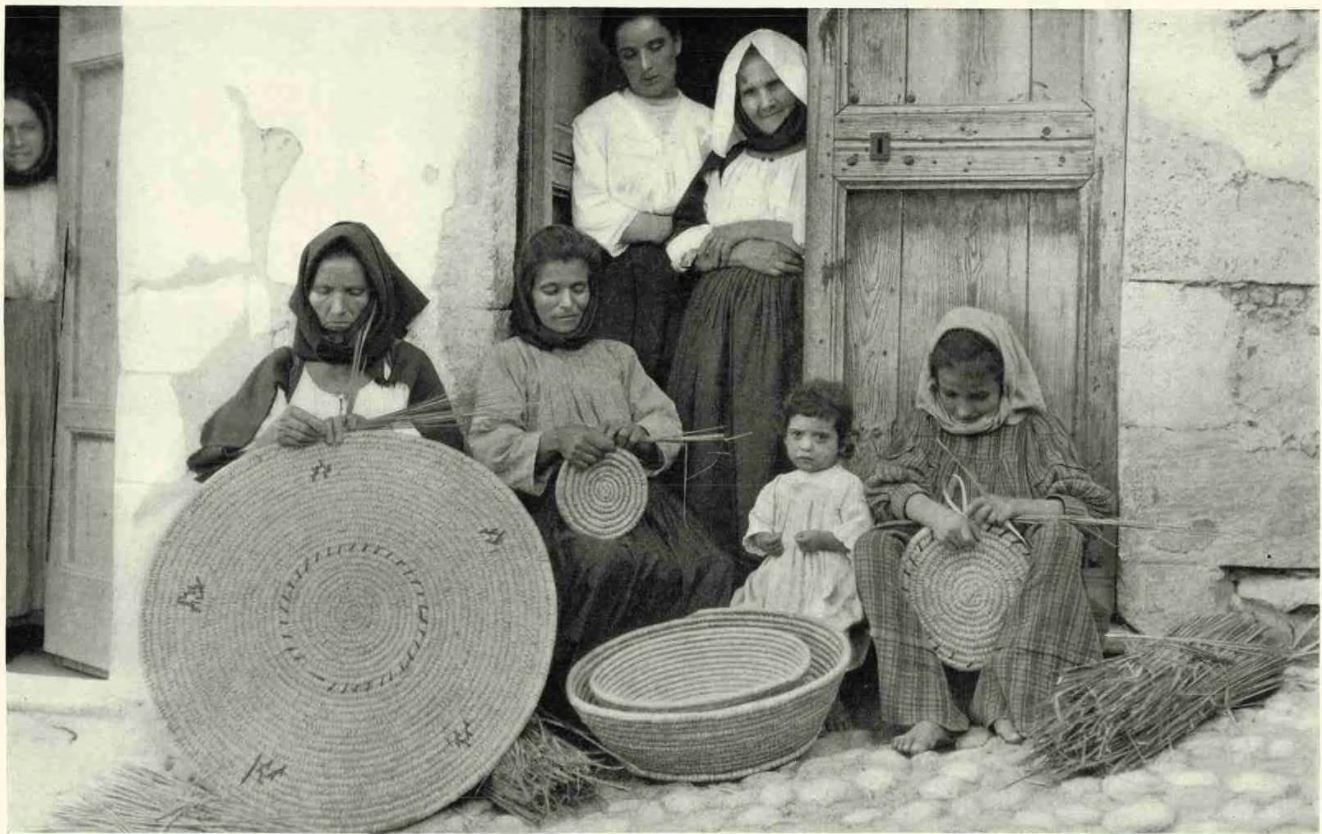

The flour thus ground is screened through sieves made at home by the women of the household (see Color Plate III). This operation is often performed in the middle of the courtyard. The bran is stored to feed the fowls, which are invariably found either here and there in front of the lolla or perched upon the cart shaft, which they use as a roost.

The contrast between the lolla full of flowers, with every comfort of modern life, elegant in appearance, and lighted during the night by electric lamps, and the other part of the courtyard, with its rural aspect, is both striking and interesting.

The lollas of the Campidano are not always the fine verandas just described. In the houses of poor families the portico is primitive, with a battered, slovenly tiled roof, supported by rough wooden posts, which are sometimes replaced by pillars of masonry. Other lollas have no, gardens in front; but always one finds flowers or a climbing plant, adding color to the wall of the house. Everywhere are evidences of the good housewife’s efforts to beautify her lolla as best she can.

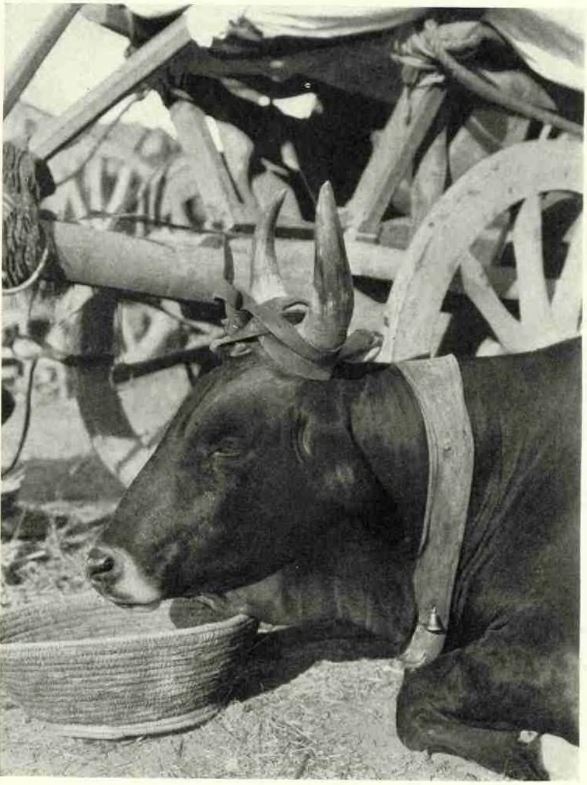

THE MOTOR CAR VERSUS THE OXCART

The courtyard of a Campidano home is always cluttered with quaint Sardinian carts, with their frames formed of long poles.

The oxcart is still to be found on all Sardinian roads, in strange contrast with the speedy motor car, to which the slow Sardinian vehicle is often a serious hindrance, for the cart is usually loaded with fagots piled to an incredible height and spread so wide that the road is completely blocked. It is often quite useless to sound the horn. No one hears, The driver of the cart sleeps and the oxen, too.

When, after a great amount of hallooing, sounding of the horn, and shouting, the cart moves slowly aside, the motor car is rudely brushed by the bristling ends of the fagots.

The roads of Sardinia, once deserted and silent, are now traversed by many motor busses. Nowadays every part of the island is easily reached in a public automobile, but the old-time cart is always there also. It moves slowly and takes days to reach a village, but now and then it avenges itself on its modern enemy, the automobile. The engine gets out of order, a spring is broken, or the magneto does not work and a ferocious sun shines over all the scene. Then the Sardinian cart takes in tow its dejected and humiliated enemy and the passengers gaze morosely at the scenery, knowing that the village is distant and that on country roads are neither inns nor hotels.

In the central regions of the island the cart is smaller and has wheels of solid wood. It is just such a vehicle as was used by the Romans twenty centuries ago (see page 55).

HOW THE WORLD MOVES ON SAN PIETRO ISLAND

In some mountain districts of the interior and on the island of San Pietro the small cart with solid wood wheels is still in use, exactly as in the time of the Roman supremacy.

The wheels are tight on the axle, which revolves underneath the cart in hardwood blocks.

NO WINDOWS LOOK UPON THE STREET

The house of the Campidano is almost always the one-storied building so common in Spanish countries. No windows look upon the street, a condition said to be due to the fact that in former days men were so jealous of their women that nobody would expose his wife or sister to the curious glances of strangers.

This reserve and all these efforts to conceal the business of the household are so common in Anglo-Saxon life that readers will not understand how it could be otherwise. Yet life in the southern part of Europe is so open to inspection that this characteristic of the villages of the Campidano deserves notice.

The heroines in Mrs. Deledda’s works are rude types, all flesh and blood, with strong passions, often unchecked by education or religion. She describes the women of that small portion of the island which is called the Nuorese. In the Campidano nothing of the sort is to be found in the beautiful, quiet, open faces of the women, whose cares are all directed to bringing up a family —women who have in their eyes the reflection of the broad green plains of their beloved Campidano and whose bucolic souls are free from any dangerous passion.

In their lollas, full of sunshine and flowers, they superintend the household. Their men cultivate the fields and tend large tracts of vineyards, coming home at sunset. The large gate is opened wide to admit the cart loaded with casks of wine or bags of corn. Then the ample courtyard with its lolla is inclosed again and the happy domestic life continues in the sanctuary of the family.

A visit, however short, to the villages situated in the northern part of Sardinia and a hurried glance at a Campidano house are sufficient to reveal the great difference which exists between the northern and southern parts of the island.

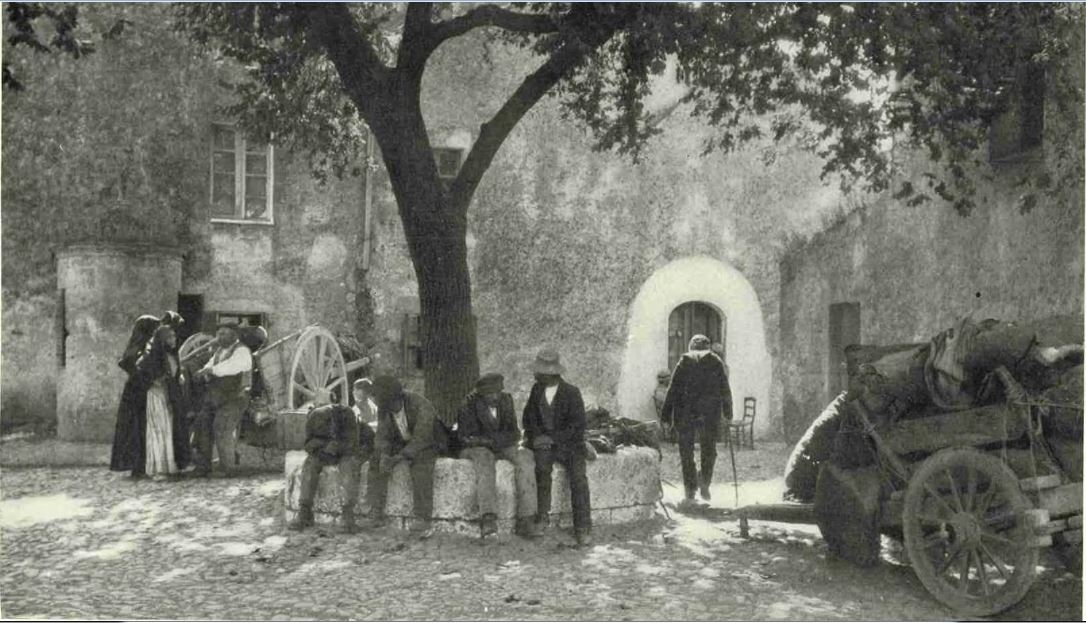

A LAZY SUMMER MORNING IN THE PIAZZA AT OSILO

This is the fruit market whenever there is any to sell, but it is always the loafing place for peasants as well as for the people of the village.

A LAZY SUMMER MORNING IN THE PIAZZA AT OSILO

This is the fruit market whenever there is any to sell, but it is always the loafing place for peasants as well as for the people of the village.

SARDINIA PROVIDES MANY CHANGES OF SCENE IN SMALL SPACE

As soon as one quits the plain and ascends the first hills, the appearance of nature suddenly changes, and before reaching the highest summits of the Sardinian mountains, one has passed through so many diverse regions, has admired such variety of scene, has been charmed by so many different costumes, that he gets the impression of having made a very long journey,

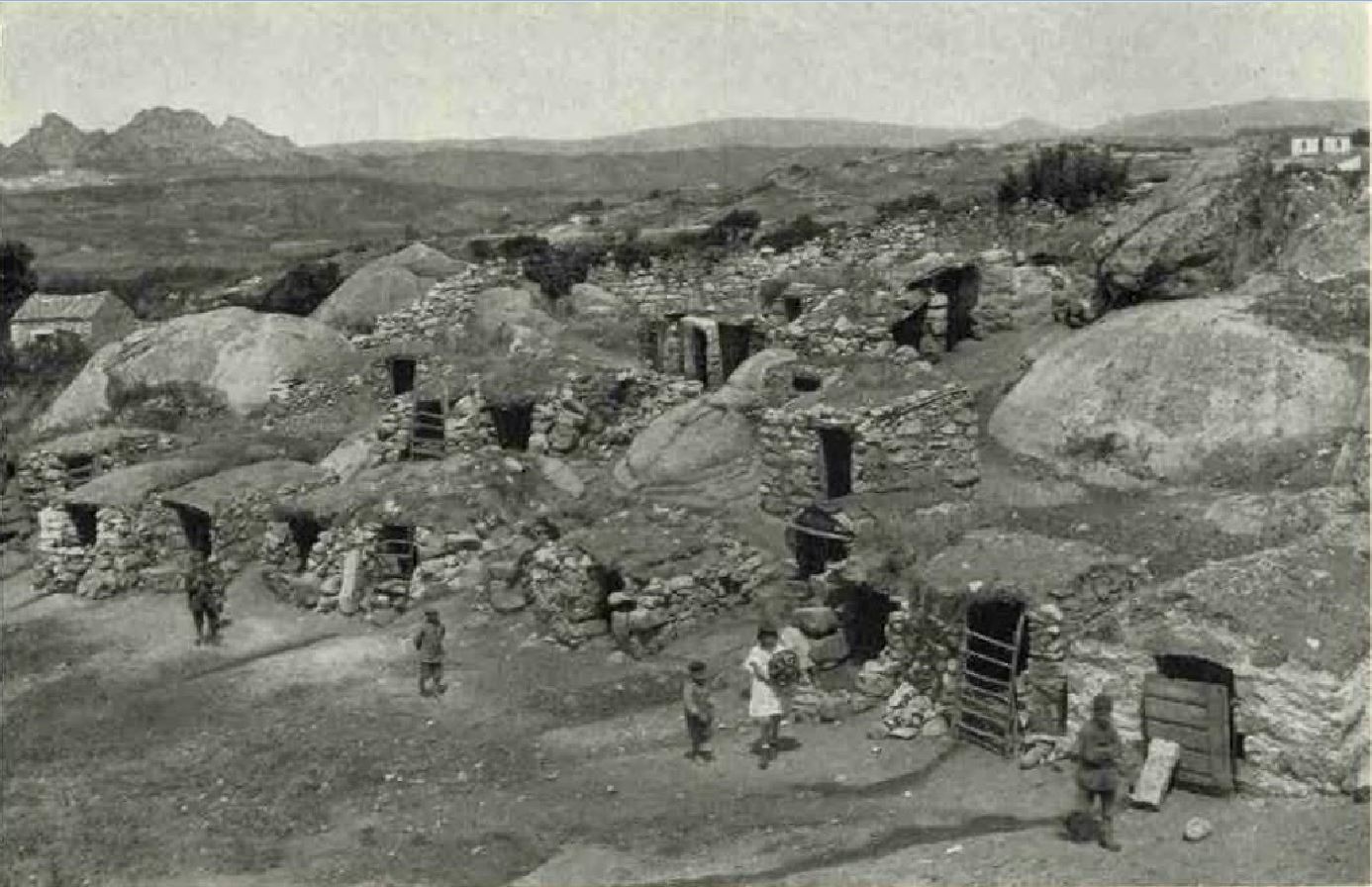

Here is Gallura, with its granite peaks and cork trees, of which entire forests cover the mountain slopes, with villages overawed by rocks which seem about to tumble down on them at any moment. There is Aggius, with its long range of saw-tooth peaks; Tempio, with its houses made of granite, giving the town an appearance unique in Sardinia; Nuoro, which combines the comforts of modern civilization with the opportunity to inspect Sardinia’s ancient customs.

Then the mountain landscapes, with their incredible contrast of colors! Rude valleys and lovely glens, orchards and gardens, and long tracts of tancas (inclosures), limited by fence walls in the northern regions and by cactus hedges in the south, all covered with asphodel and aromatic herbs, with flocks of goats pasturing on bafren slopes.

Then there are Oliena, with the resplendent costumes of its inhabitants, and Fonni and Orgosolo and Desulo, the sad village losting the solitude of woods, where dwell the most beautiful women in Sardinia, all dressed in red, a color which becomes a mass of flame when a procession of praying women is projected against the intense green of the chestnut woods.

In the district called Ogliastra are Lanusei, Arzana and Villagrande, villages which command extensive and magnificent views — a series of hills towering one beyond the other as far as the sea which washes the shore of Tortolì.

On the western side is the marshy district of Oristano, so powerful and important when Eleonora d’Arborea reigned, and near at hand Cabras, a village situated on the shore of a large pool, rich in fisheries, but unhealthy, where, in the summer months, malaria kills many of the inhabitants.

The villages in this part of Sardinia are almost all in miserable condition, for the delta of the Tirso is very unhealthy. But when the great irrigation works are finished its course will be better regulated, and it is believed that dread malaria will disappear.

There one sees pale girls, with fevered eyes as black as a raven’s wing. They ate barefooted and wear a colorless costume as somber as their countenances. Even the peculiar head-dress, which consists of a bright yellow kerchief tied under the chin, serves but to render the faces more sad and pale. What a difference between them and the pink-cheeked, blue-eyed, black-haired girls of the mountain district! Yet both are daughters of the same land.

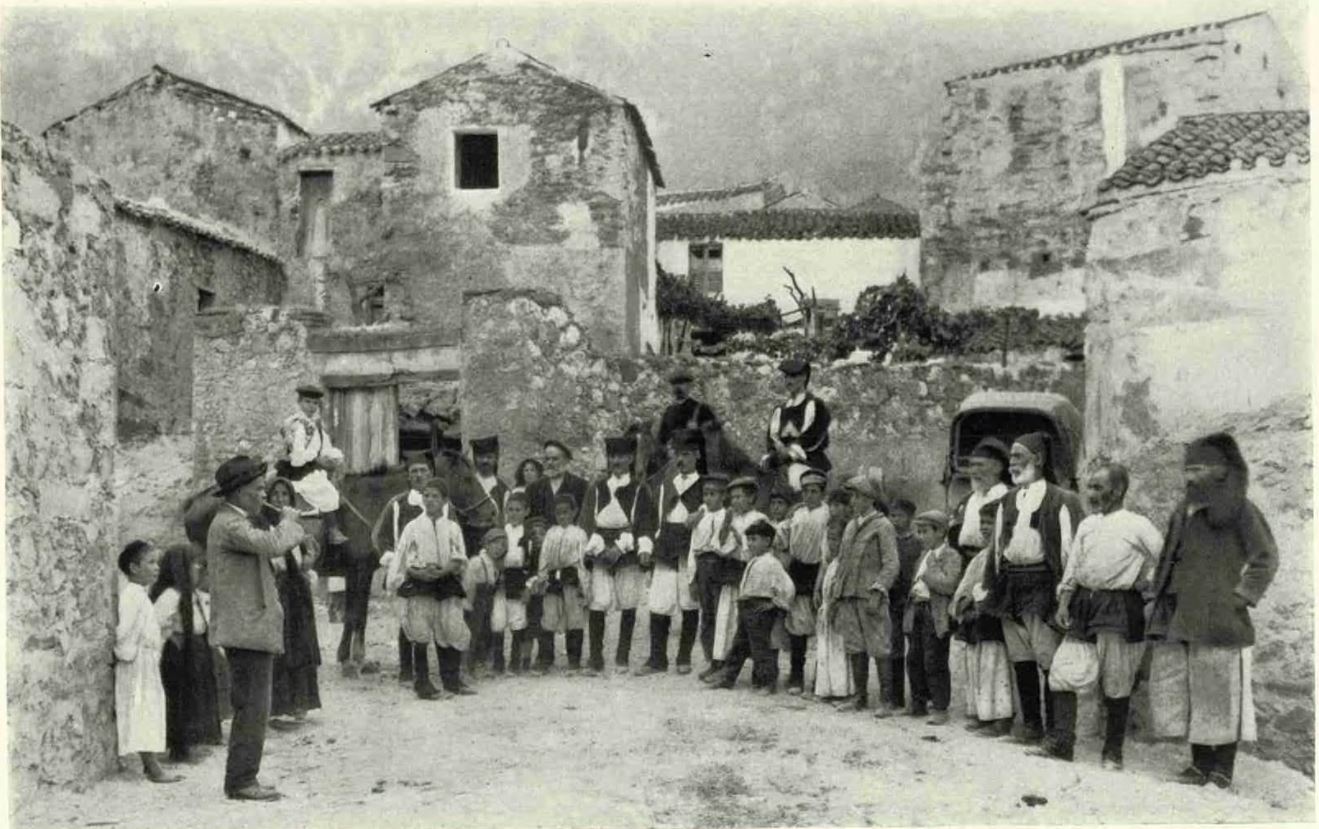

THE TOWN CRIER, OR “BANDITTORE,” MAKING AN ANNOUNCEMENT IN A MOUNTAIN VILLAGE

Between blasts of his little brass horn he is telling the assembled crowd that fine watermelons may be bought at the first house south of the church.

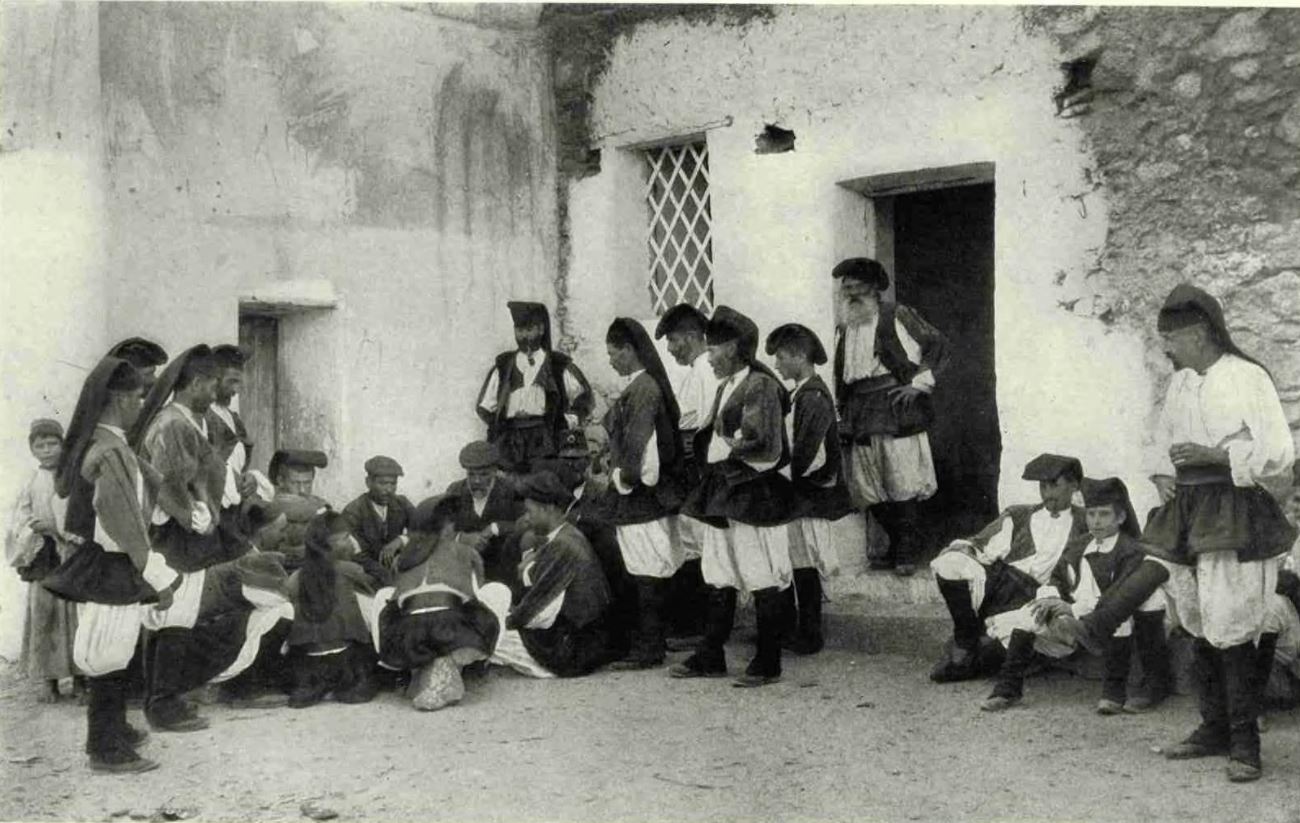

A SUNDAY MORNING GATHERING OF PEASANTS IN OLIENA

The men enjoy card games during the afternoon and all join in the dance held in the principal piazza after dark.

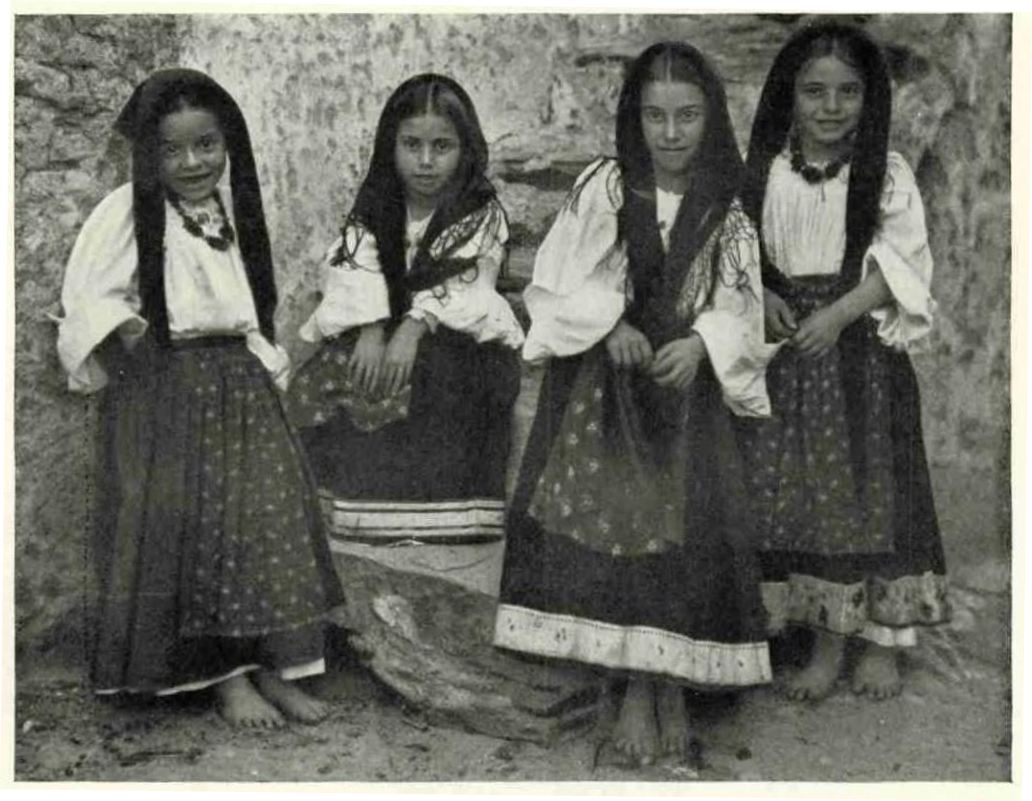

THREE GIRLS OF DESULO

Even the dolls in Desulo are dresed in the coarse, red orbace, so it’s quite natural for the children to dress as their mothers and older sisters do.

WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN THE COSTUME OF DESULO

Made in the home, of coarsely woven mountain wool, this costume owes its color to a fruit and vegetable dye the secret of which was sought by German experts before the World War.

LITTLE WOMEN OF OLIENA

Dressed in the same costumes as the older women, these girls seem never to have had a childhood. ‘They were very shy and solemn, for this was the first time they had ever been photographed.

ARITZO PEASANTS PLAYING THE SOUTHERN ITALY GAME OF “MORRA”

The players try to guess the number of fingers held out at the instant the hand is thrown forward. It is a favorite game in the drinking places and at fetes, but is prohibited in some cities in Italy on account.

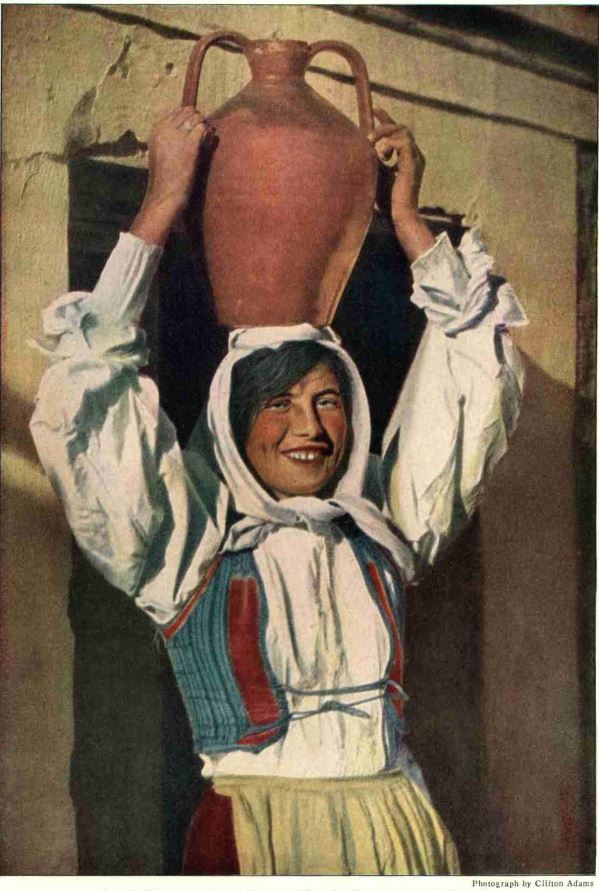

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

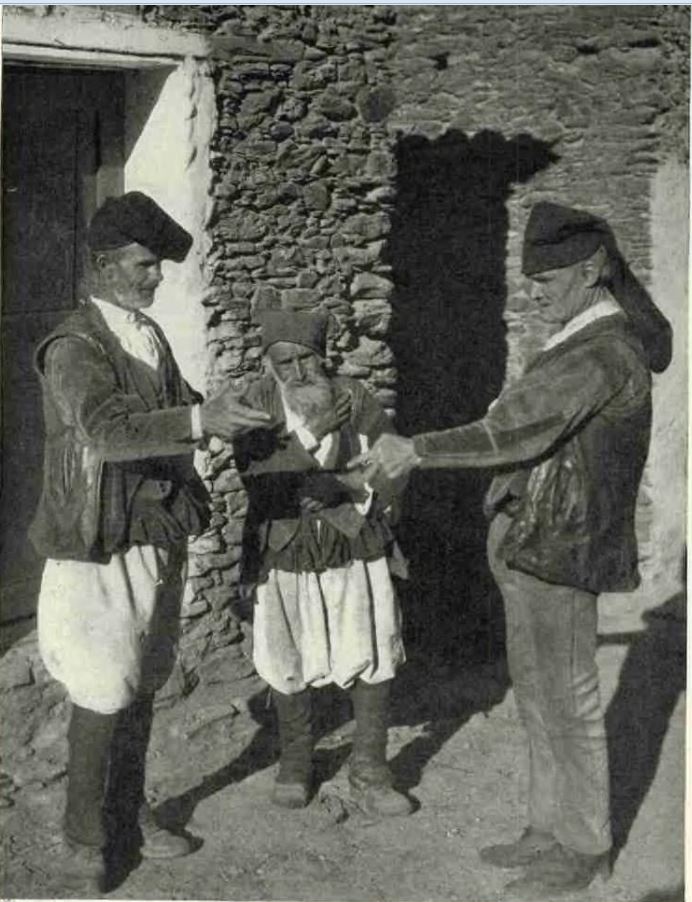

MEN OF THE DORGALI NEIGHBORHOOD ON THE EAST COAST OF SARDINIA

Their handsome costumes are set off by the rough “mastruca” [Goat skin dress, sleeveless, almost knee-length, worn by Sardinian shepherds] of black lamb’s wool with pockets of hand-tooled leather in artistic designs. The native costumes are slowly giving way to cheaper and less distinctive garments.

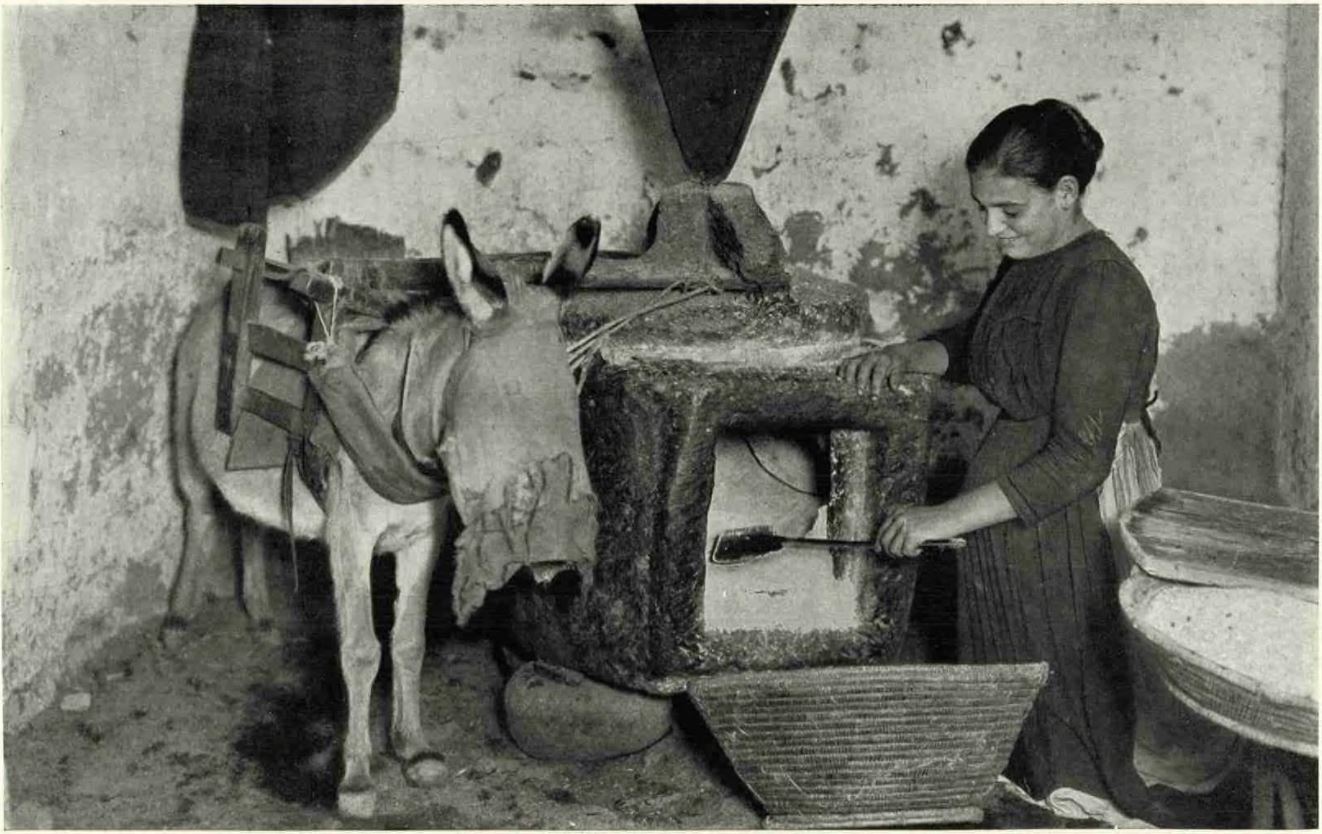

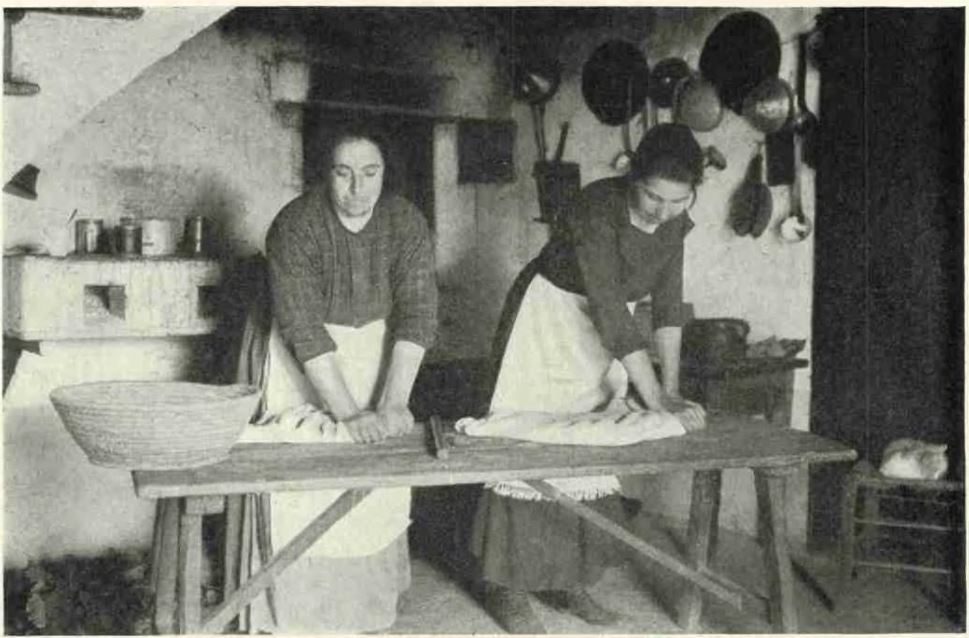

BREAD-MAKING IS AN IMPORTANT OPERATION

One of the most important operations in Sardinian villages is making bread, for it is the chief food of the peasants.

When they have to work in fields distant from their homes, they carry with them enough bread to last a week. Once a week every Sardinian housewife is busy making bread, and until late at night she is superintending the maidservants, who olay the utmost activity in the performance of this domestic duty and are helped by every member of the family.

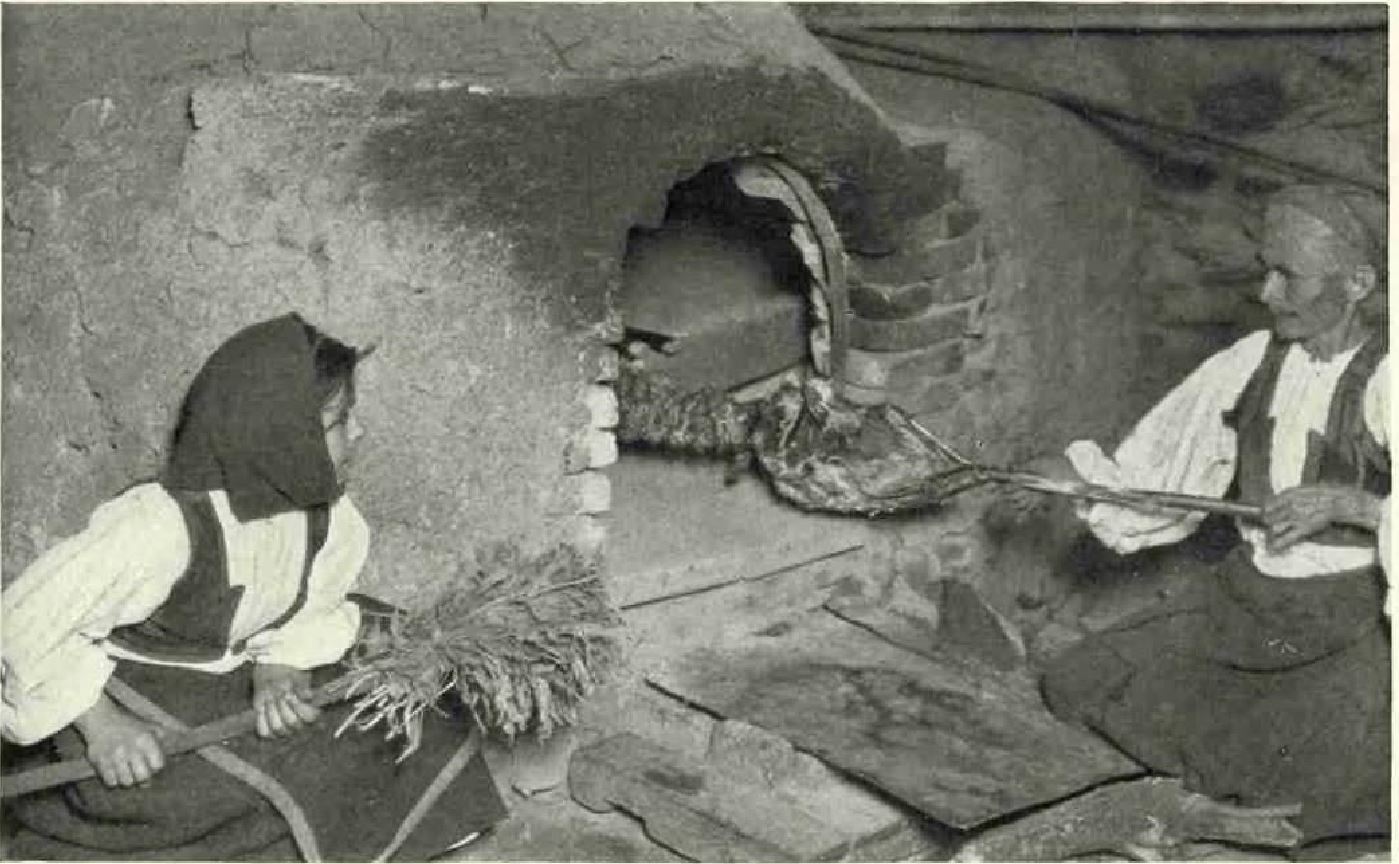

The oven must be heated, fagots heaped close at hand, and the fire carefully regulated, for as the quantity must last a week it must be well prepared in order that it may not become stale. From village to village the shape in which bread is fashioned varies considerably, and even its composition presents slight differences.

The kneading of the flour is conducted in the kitchen, often in large earthenware bowls, but it is finished on a table so short-legged that it compels the operator to kneel before it. The dough is rolled very thin. When baked and cooled, it becomes so hard and brittle that it cannot be broken without crumbling into innumerable bits.

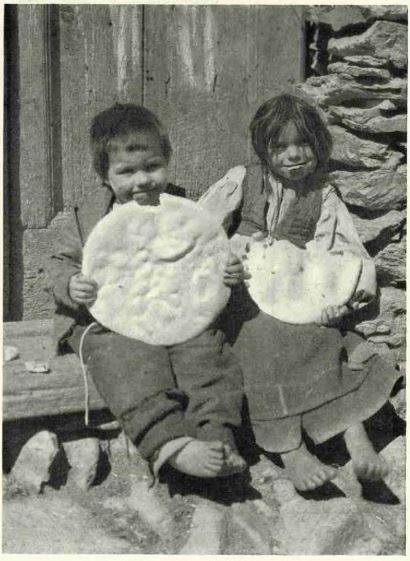

This bread, having little yeast in it, lacks the flavor of the fermented variety, and has different names. In northern Sardinia it is called carta di musica (paper to write music on). In Barbagia, as at Desulo, Aritzo, and Sorgono, they call it pillonca.

In autumn, flies are a great nuisance in Sardinia. They cover every inch of the kitchen tables and every particle of food. In the Campidano houses, whose main features are cleanliness and order, these winged pests have relentless enemies in the housewives, who employ all means to banish them; but in the villages situated in the center of the island, where cleanliness is not at all in accord with the beauty of the scenery, the tourist unaccustomed to such sights becomes terrified and swears neyer to taste such bread, remembering his lessons in hygiene. He wonders how the people live and thrive.

Fortunately, the fire which burns briskly inside the oven destroys the germs. The aromatic shrubs by which it is fed send out a smoke which has a distinctive odor.

Instead of escaping through the chimney, it often oozes out between the weathered tiles of the roofs. The whole village reeks with smoke, which tells the visitor that it is baking day.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

MAKING FLOUR IN A SARDINIAN HOME

After the wheat has been ground in the donkey mill it is screened through sieves of cane splints into large palm-leaf baskets. Then it is passed through silk bolting-cloth sieves to obtain flour fine enough for the unleavened bread which is baked in mud ovens.

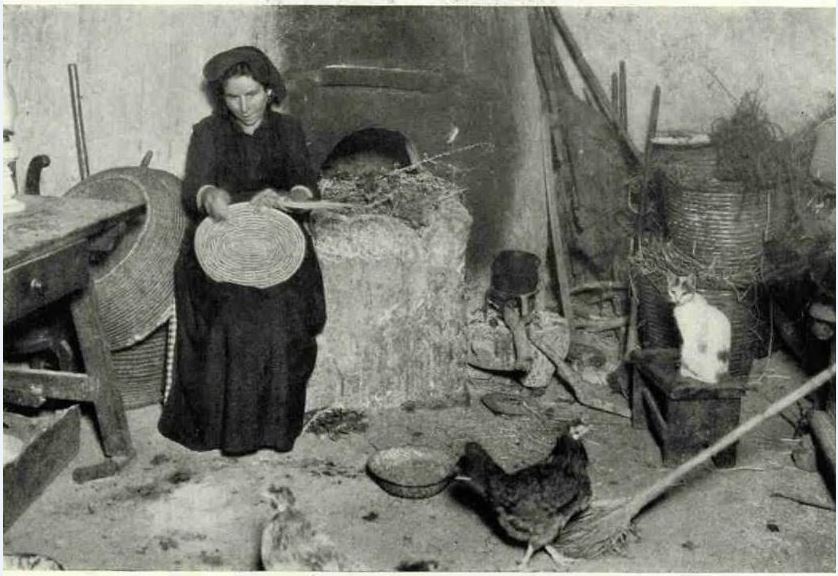

A HOMEMADE FLOUR MIL, IN A SARDINIAN KITCHEN

The rock is the black lava of which the prehistoric nuraghi are constructed. The mill is of the same model as those unearthed at Pompeii and Herculaneum. The entire process of cleaning and grinding the wheat, sifting the flour, and baking the coarse unleavened bread is done in the home.

KNEADING THE DOUGH

In some Sardinian homes the task of bread-making is confined to one day each week. is prepared in the morning and baked in the afternoon. The loaves dough for the week’s supply. The are hard and dry at the end of the week and are often hacked to bits with a big knife.

PREPARING BREAD FOR THE OVEN

The dough for the large, thin, circular pieces of bread known as “carta di musica” is brought to the rolling-board in large balls in a basket. On account of the swarms of flies found everywhere, the loaves are wrapped in a long piece of cloth, then carried in a tray on the head to the nearest oven for baking.

TENDING THE OVEN IN A DESULO COTTAGE

Dry mountain underbrush is used as fuel in these ovens of mud. Long spits of mutton are roasted in them for the wedding feasts, which sometimes last for several days.

EATING “PILLONCA”

The unleavened native bread of Sardinia, which is about half an mch tick and is baked in large disks from 14 to 18 inches in diameter.

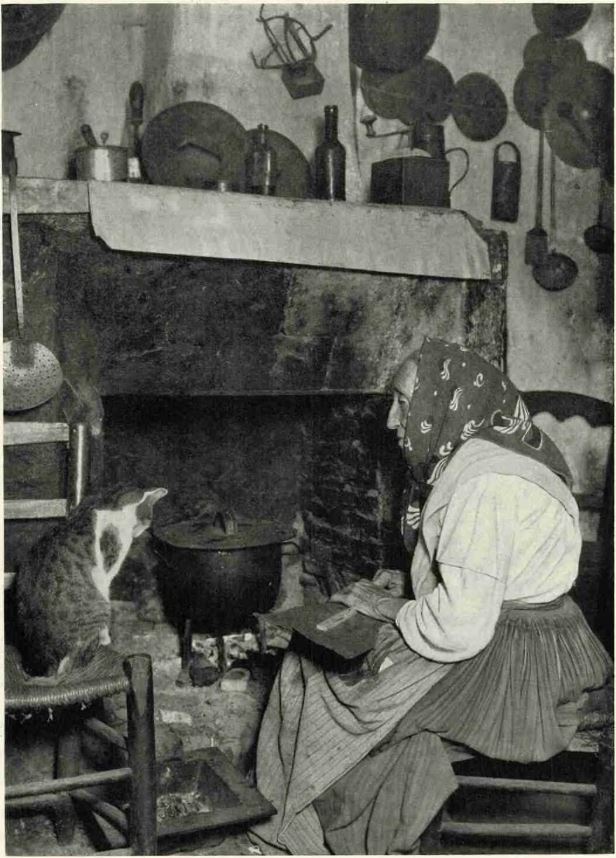

PREPARING THE EVENING MEAL

In many of the poverty-striken ho of the mountain villages it is the grandmother who fans the blaze in the fireplace to cook the fami supper, us y one dish consisting of a mixture of vegetables.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

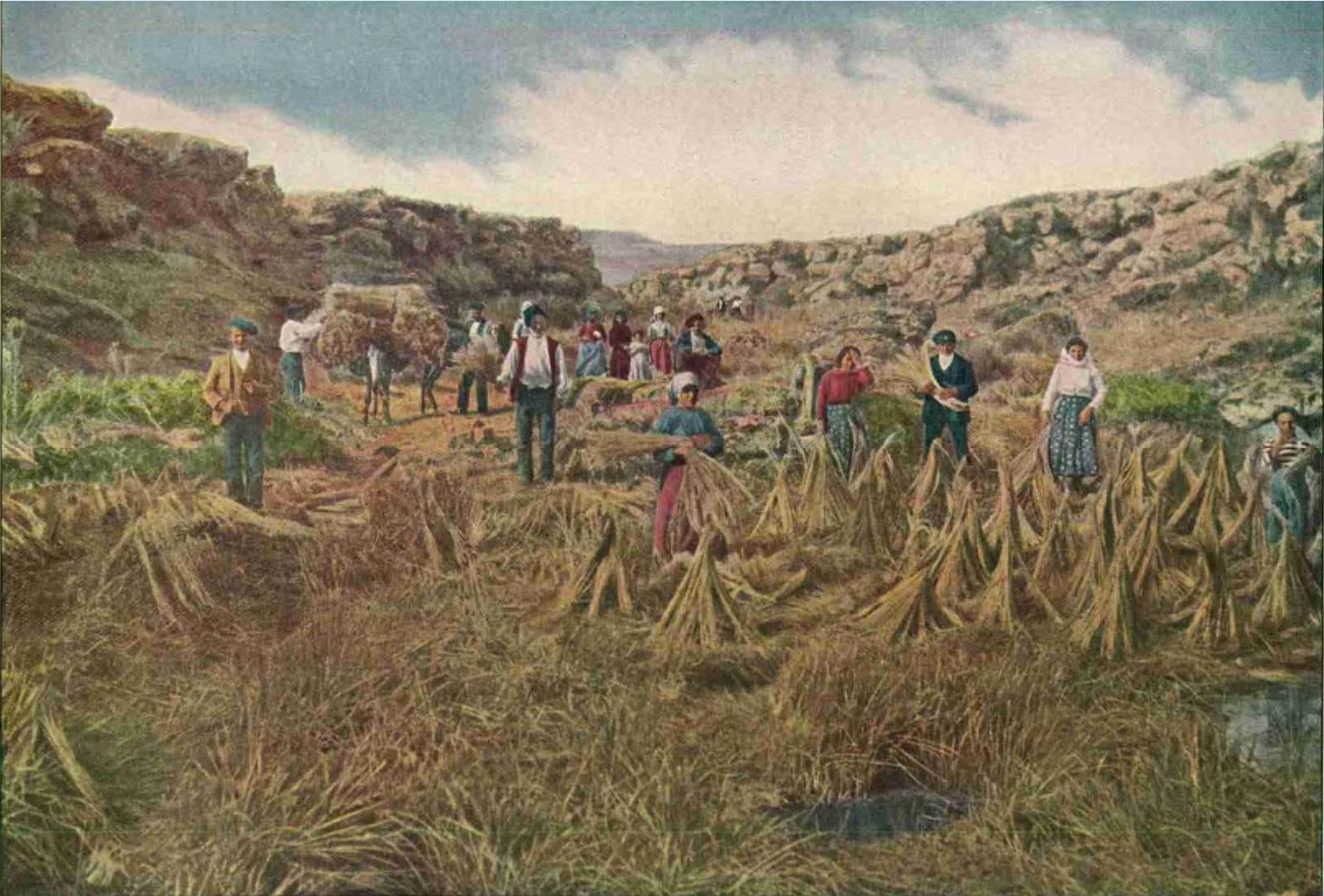

MEDITERRANEAN PASTORAL SCENE

A Sardinian peasants make excellent use of their natural resources. This flax straw lay in the stream for five days until the white fiber swelled. Now the hundles are being dried and taken on mule-back to the farmhouses, where the women will weave it into fine white linen.

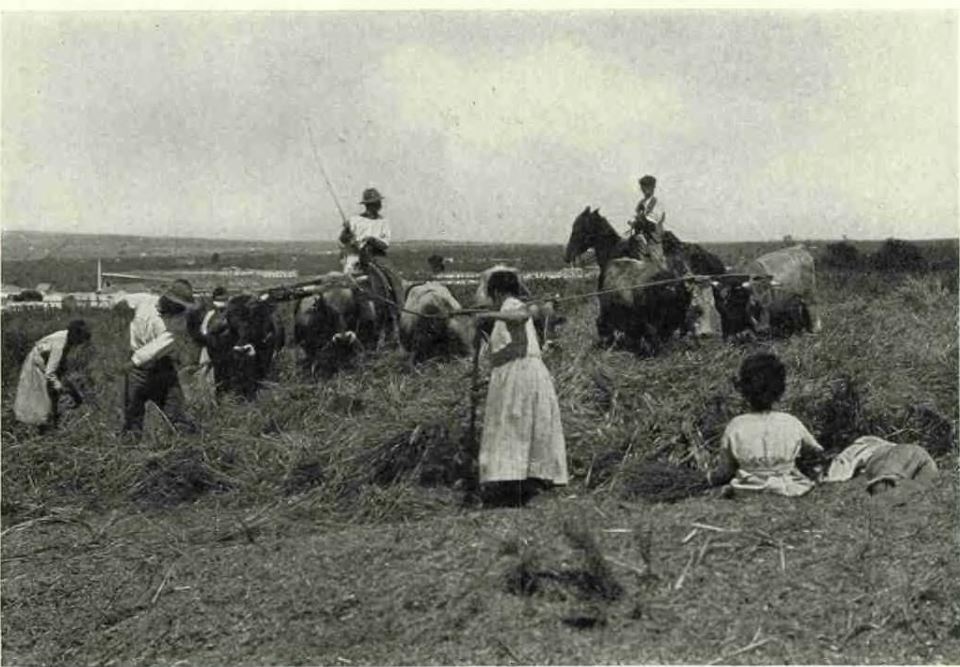

THRESHING WHEAT

The grain is shelled from the head by the steel-shod hoofs of the oxen as they pass many times over the straw. Afterwards the straw and chaff are tossed in the air with forks, and the wind winnows the wheat.

AFTER THRESHING THE STRAW IS BALED

Sometimes the straw is piled in this fashion on the plains near the railway stations, to await shipment during the winter months.

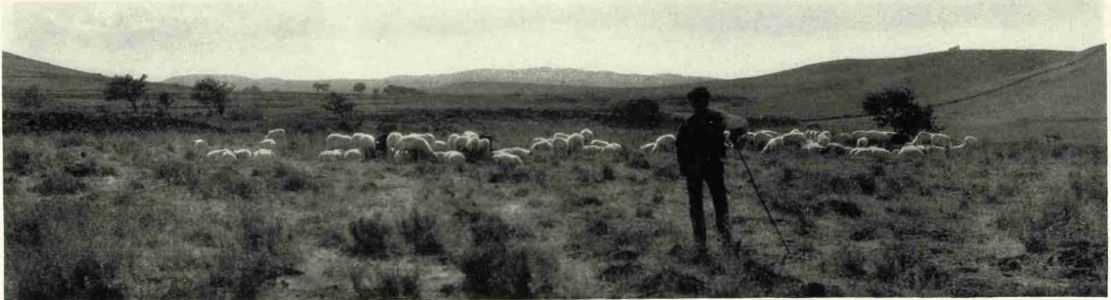

EVENING ON THE PLAIN OF MORES, NEAR TORRALBA

There are many flocks of sheep on the flat pasture lands, cared for by shepherd boys.

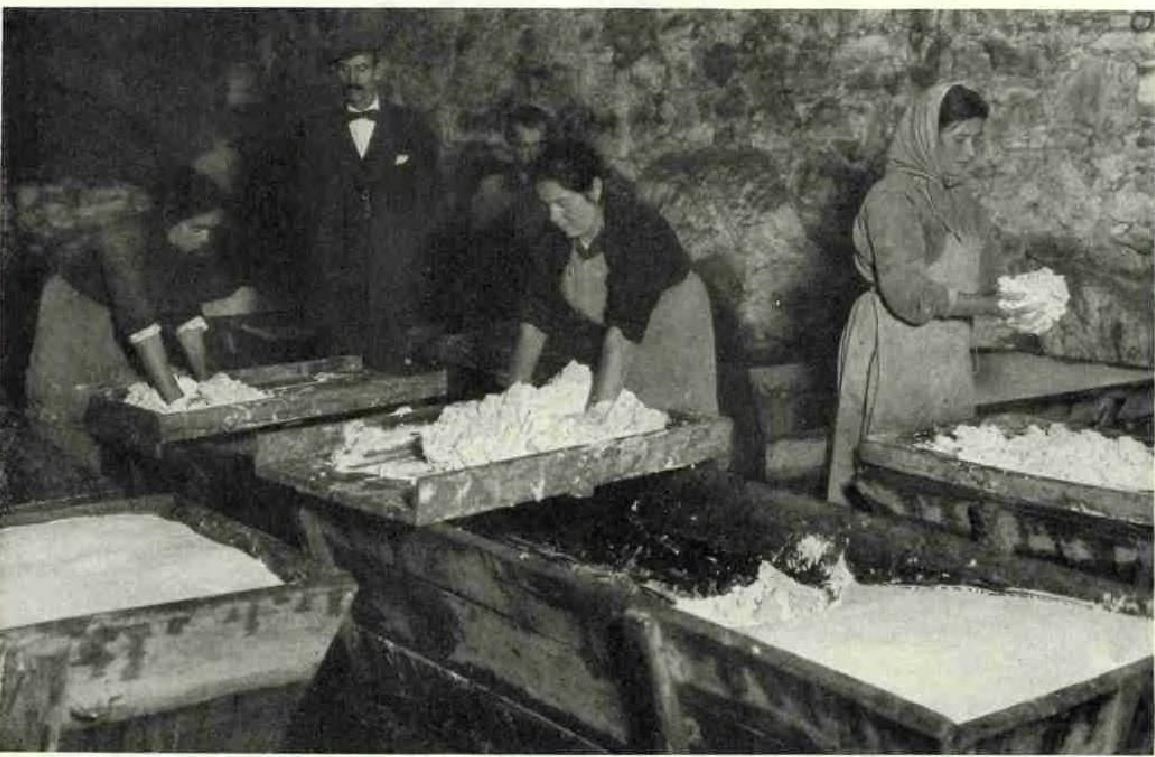

PREPARING GOAT-MILK CHEESE

This cheese of Macomer has aged for five months, May to September, and after two or three more workings and the addition of olive oil and other ingredients, it will be ready for market in the winter.

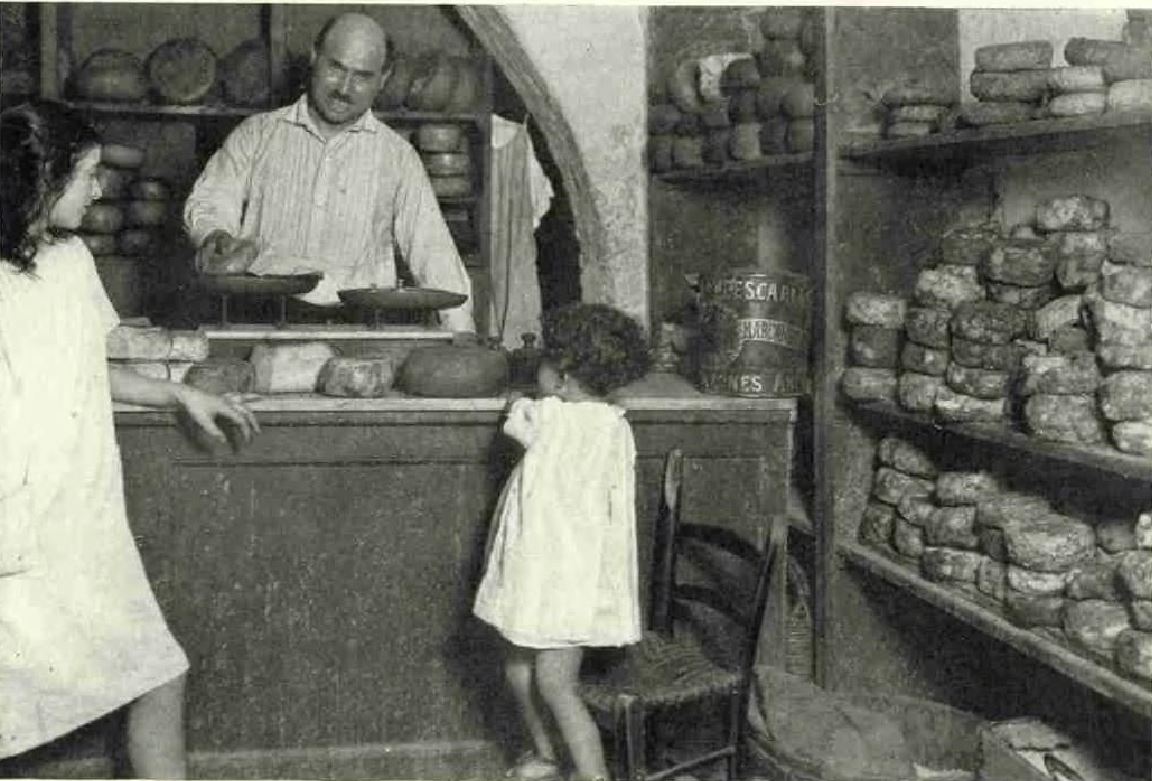

INTERIOR OF A CHEESE SHOP

Here the cheese lover may find all varieties of Sardinian cheese. ‘The smell is terrific and some of the wares on the shelves seem as if they might have attained a ripe old age before Columbus set out on his famous voyage.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

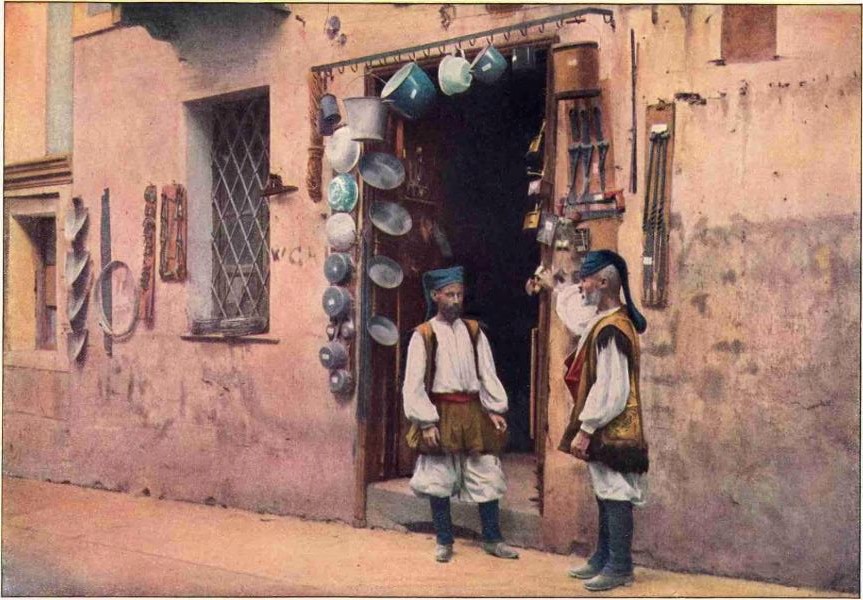

A VILLAGE HARDWARE STORE IN SARDINIA

The shops in the mountain villages of Sardinia display a variety of cheap household utensils. These are bought a piece at a time by the poorer peasants to grace the walls of their homes when not in use in the fireplaces.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

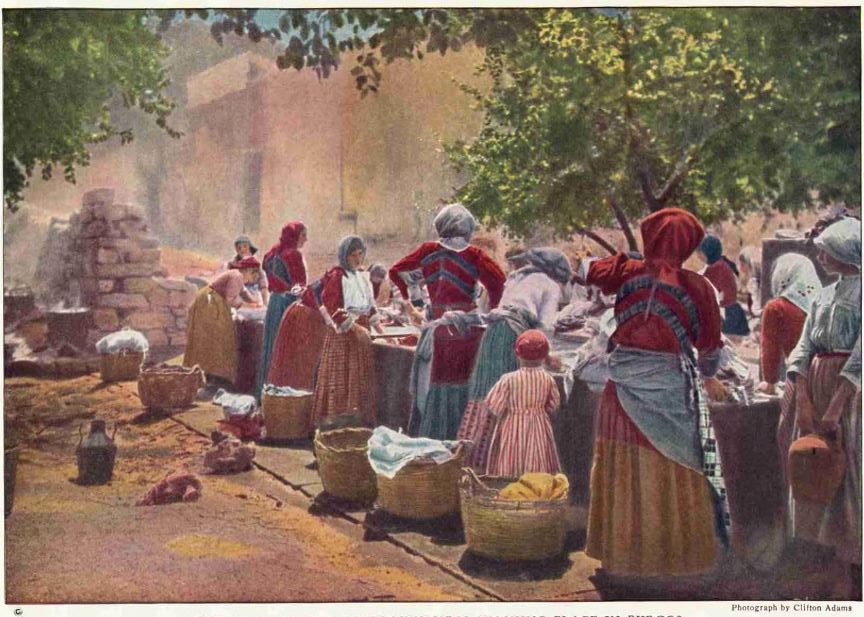

MONDAY MORNING AT THE MUNICIPAL WASHING PLACE IN BURGOS

Wash-day in the Sardinian mountains presents an animated scene with rows of peasant women in bright costumes working on each side of a long trough. In the background are black kettles over open fires to heat the water.

A BUSY MONDAY MORNING SCENE NEAR PORTO TORRES, NORTHERN SARDINIA

As there is no water piped into the home, this brook is a blessing to the housewives, who bring their washing here, balanced on their heads in large tin cans. The clothes after being washed are spread on bushes to dry in the hot sun.

CURIOSITY IS A CHARACTERISTIC OF THE ISLANDERS

In the villages the people are rather inquisitive. They gather around the tourist and ply him with questions, seeking to know everything about his errands. At Desulo particularly the women are tremely curious. “Why did you come? “Are you single or married?” “Where do you intend to go?” Such questions every visitor must answer if he desires peace.

If he carries a camera, the affair becomes even more serious. Children, as numerous as flies, collect around the unhappy man, and are so bold as to thrust themselves even between the legs of the camera tripod. Each wants his picture taken, and has uncanny ability in finding the very spot where he is not wanted.

When, at last, everything is ready and the shutter is about to be released, a boy who has succeeded thus far in escaping attention comes up and peeps into the lens. So goes another film!

Whoever carries a camera is often asked, “How much do you charge for a portrait?” It is rather difficult to make the people understand one’s reasons for taking photographs. Pretty girls often object to posing before a camera, for fear that their likenesses will appear on a picture post-card — a thing which they abhor above everything else.

They are Eve’s daughters, however. When asked to pose, they pretend to be shy, and giggle and cover their faces with aprons, and say that by no means will they allow any one to take their picture. But they do not stir; they do not run away. The ending is almost sure to be a happy one for the zealous photographer.

AN EXCEPTIONAL BLOND TYPE OF ISLAND MAID

Although she lives in a village in a barren mountain region of Sardinia, she is not unlike an American in features, dress, and actions.

CLOTH MADE AT HOME FOR PEASANT COSTUMES

In the mountain districts in the heart of Sardinia and in some of the northern villages — Osilo, for instance — the cloth of which the peasant costumes are made is woven at home. The spinning is done by women whose parchment skin, sunken eyes, and protuberant cheek-bones suggest a grotesque mask.

The warp is stretched on the ground in open spaces to prepare it for the loom, at which women and girls work all day, singing their melancholy songs to the accompaniment of the click-clack of the sley, which forces the weit into place.

One variety of fabric so woven is called orbace. From a modern point of view it lacks smartness, for it is rather rough and hairy, but it is so strong and so nearly waterproof that officers of the Italian navy, sailors, and sportsmen buy a great deal of it for suits and overcoats.

For women’s dresses, the cloth is dyed black, scarlet, or dark red. The peasants use vegetable dyes extracted from the juice of certain berries, and neither rain nor sun can fade the colors, German chemists often studied the plants from which these dyes are taken. In vain they urged the Sardinian women to use the bright aniline dyes. Some villages experimented with them, but they proved a failure. The contrasts were unpleasing, the tints too bright; the whole effect was inartistic.

CARPETS AND SADDLEBAGS ARE PICTURESQUE

From varicolored wool the Sardinian women weave carpets and saddlebags which are truly wonderful, both for variety of pattern and harmonious combination of colors.

The sense of art in these uncultured people makes a modern painter wonder how women who live so far from any recognized art center succeed in originating such pleasing designs. From generation to generation a natural taste has been handed down by these modest people, who embroider their skirts and bodices and make such splendid carpets that no trained artist could do better.

AN ANCIENT HOMEMADE LOOM IN A PEASANT COTTAGE

The women of Sardinia are experts at weaving, an art handed down from mother to daughter for generations.

The cloth is usually of pure wool from the native sheep and the capacity of the loom is 8 to 11 yards a day.

MAKING READY FOR HER PRESSING

A familiar sight in Sardinian villages is the housewife seated at the door of her home with her large sad-iron. She fans the charcoal into life to heat the iron.

[SARDINIAN FESTIVALS]

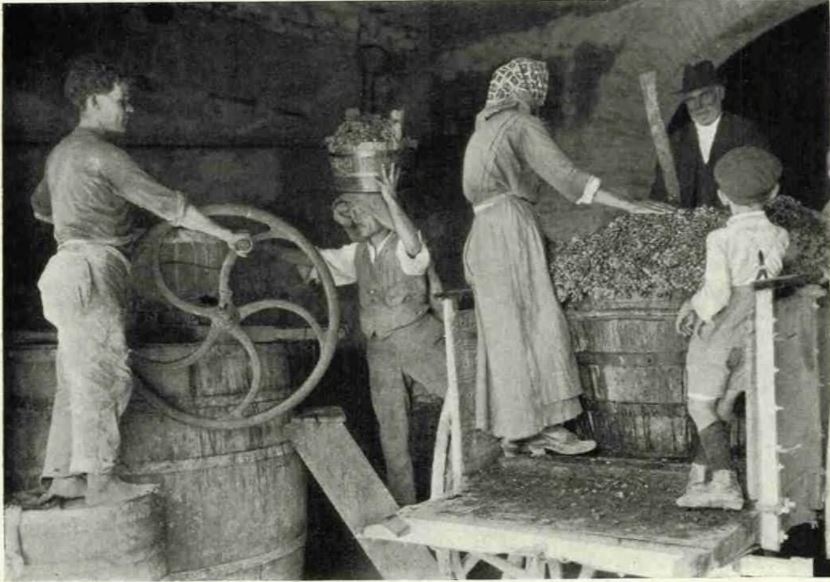

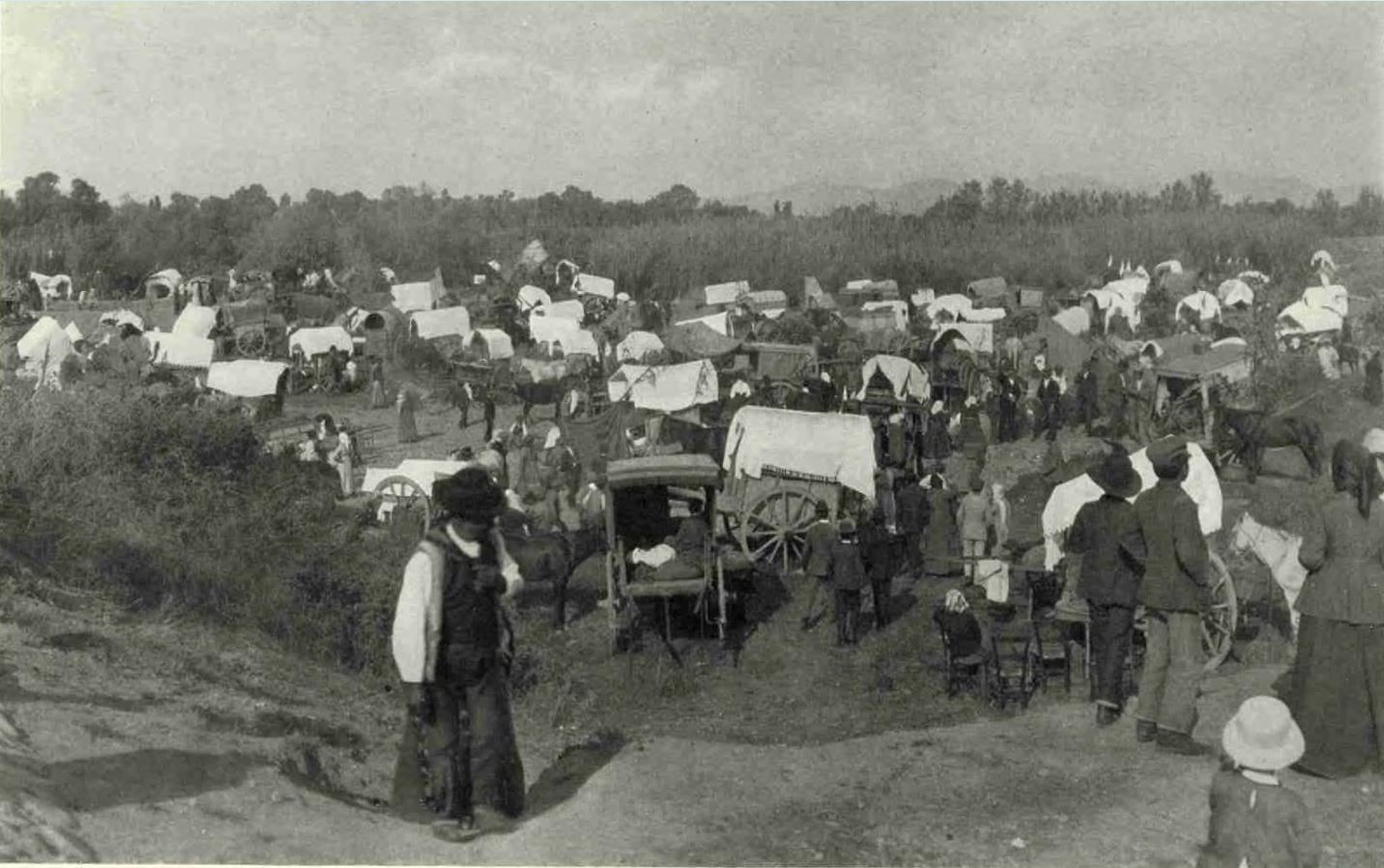

From June to October the Sardinian calendar contains many festivals. Saints, both male and female, are held in high esteem, but religion is more the occasion than the cause for releasing the flood of music, pageantry, and rivalry. The Spaniards are largely responsible for this trait of Sardinian character.

Whole families of peasants think of the feast two or three months in advance. They hoard every penny and endure great want with the sole aim of spending in one happy day what they have accumulated during weeks of glad discomfort. They travel from distant places in carts covered with tunnel-like awnings and drawn by bullocks or horses.

FURNISHINGS OF A PEASANT CART

The furnishings are simple. A pair of homemade chairs are securely fastened to the sides of the cart for the mistress and any other important personage of the household, The others accommodate themselves as they can on mattress or cushions. The cart is cluttered with household treasures: saddlebags filled with cheeses, bread, potatoes, lambs or kids ready-slaughtered but not yet skinned, caldrons, earthen cooking pots, and children of all ages and complexions, not to mention a lean, underfed cur which is compelled to trot under the cart, to the shaft of which the poor animal is tied by a short rope.

Sometimes the cart is so full that there is no room for the driver, who is compelled to sit on one of the shafts and from there guide the unhappy horse.

No springs deaden the violent jolts which bad roads impart to the vehicle; but the enthusiasm of the travelers is not at all abated by the incommodious cart, and the party finally arrives at the spot where the feast is to take place, a little out of breath from the continuous shaking, but in the best of spirits and eager for all the diversions the feast may offer.

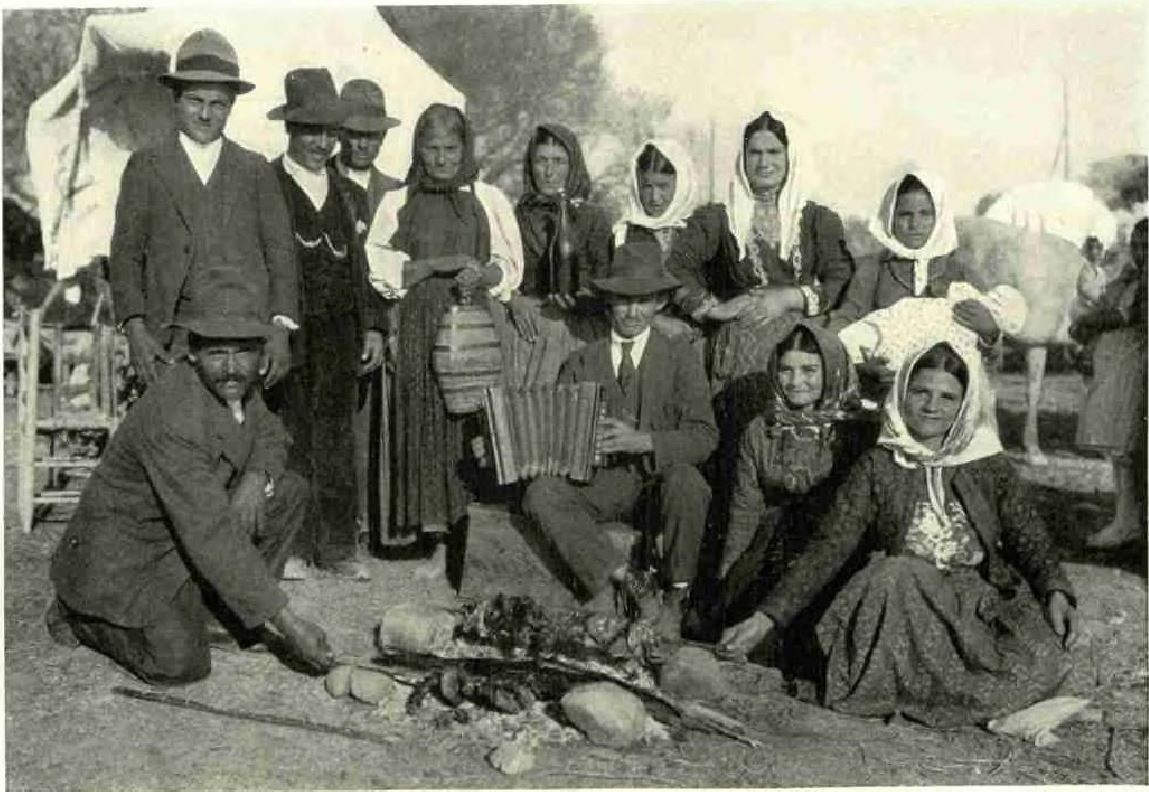

A GROUP OF PEASANTS IN CAMP DURING THE FESTIVAL OF SANTA GRECA

Many families from the Campidano, north of Cagliari, come with cooking utensils and musical instruments and camp out for the duration of the festival.

PEASANTS CAMPED IN THE DRY BED OF A STREAM AT DECIMOMANNU DURING THE FESTIVAL OF SANTA GRECA

AT THE ANNUAL FETE OF SANTA GRECA

The peasant families come to Decimomannu in their carts and stay two or three days, They camp near the town and roast pork and mutton by their camp-fires. An accordion or other musical instrument is as indispensable as the cooking utensils.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

PEASANTS OF THE CAMPIDANO AT THE FIESTA OF SANTA GRECA

The father has just bought a suckling pig at the butcher’s little grass hut, and the family is pleased in the anticipation of the roast before the camp fire. This fiesta is held in Decimomannu, whence a branch railway runs to Iglesias and the west coast.

THE WIFE WORSHIPS FOR THE FAMILY

Religious duties must not be overlooked. Wax candles are devotedly taken to the church and placed before the shrine by the housewives, who remain all the morning on their knees before the picture or the statue of the saint, while the rest of the party is busy preparing dinner.

All the cooking operations are performed in the open air. A fire is made and long wooden spits on which entire kids are put to roast are turned between two stones before the fire. ‘This method is called furria, furria (turn and turn) and Sardinians employ it to perfection.

Casks of wine are put in the shade. Cheese, bread, and vegetables are taken out of the bags, and when, at noon, mass is over and the procession has taken the saint back to the church, the banqueting begins and great merriment reigns.

After dinner the music begins. The accordion is in great demand and so is the launedda, a kind of pipe especially common in southern Sardinia. Songs are heard everywhere. In the late afternoon the people get ready for the dance.

The festivals, which generally take place in small churches situated at a little distance from the village, are more or less picturesque, according to the costumes worn by the men and women and the beauty of the surrounding scenery. They offer a capital opportunity for studying the customs and habits of the people. It is a pity that such feasts occur in a season which is not really favorable for the tourist.

HOW THE SARDINIANS DANCE

In the Ballo Tondo or Duru Duru the dancing partners join hands in a circle and wind to the left with a step rather difficult to describe and equally difficult for a novice to perform. This dance is but a memory of long-forgotten rites, when Baal and Astarte were the popular gods. The dancers hold their bodies erect, their countenances are stern, and the feet move continuously, advancing or receding with little leaps and bounds, all performed on tiptoe.

Now and then, when the dance has reached the utmost excitement, the male partners suddenly break out into wild shouts, but soon silence reigns again. The ladies dance with grave demeanor, with lowered eyes and modest mien. Any one may join the dance, but the newcomer must be careful not to break the circle to the right of a male dancer, as it is considered a serious offence to separate a couple. ‘That is logical enough. When a young man invites a girl to dance he offers her his right hand, and in so doing chooses her as his partner.

A FESTIVAL DATING FROM I6TH CENTURY PLAGUE

In the two most important towns of Sardinia, where civilization has had the deepest influence, some old religious festivals have survived, and though they have lost much of their primitive splendor they are still popular. At Sassari, on the 14th of every August, a great procession takes place which has not a wholly sacred character, but is a compromise between a religious procession and an English pageant.

After the terrible plague which destroyed so many inhabitants in 1582, the people made a solemn vow to carry in procession a certain number of huge wax candles, to be placed, all lighted, around the statue of the Madonna di Mezz’Agosto (Middle of August); but as such tapers proved expensive, the people sought a cheaper substitute. Accordingly, wooden candlesticks were made, and to these are fastened banners of different colors and patterns, the whole ornamented with tinfoil and tinsel.

Every corporation and trade union has its own candle, manifesting a certain pride in decking it. The various members who follow it in the procession hold large silk ribbons attached to the capital of the column, and while the candlestick, carried by the stoutest and strongest porters to be found in Sassari, goes down the main street, the members who have wrapped upon their arms yards and of gorgeously colored ribbons slowly them out to their greatest length.

It is a very beautiful sight to see all these silk ribbons glittering in the last rays of sunset and waving in fanciful evolutions, as those who hold them in their hands advance or recede. No priests are in the procession. At the rear walks the mayor of the town, surrounded by the council members and protected from the pushing of the eager crowd by the municipal guards in full-dress uniform.

Most of the corporation members wear quaint old Spanish costumes and the whole procession is enlivened by the sound of small drums, beaten frantically and continuously while the pageant lasts, and by the sharp notes of flutes, which play a tune so gay that it makes the stout porters unconsciously assume a gait which has all the rhythm of a ballet. When the procession finally reaches Saint Mary’s Church the candlesticks are placed around the statue of the Madonna and the feast is over.

Another religious festival, the most renowned and characteristic of all, is the festa of S. Efisio, the patron saint of the Province of Cagliari.

The ceremony takes the form of a procession to and from Pula, a village situated on the south side of the Gulf of Cagliari, where, according to legend, the saint is believed to have suffered martyrdom. The image of the saint, an ugly, garishly colored wooden statue shiny with varnish, is carried in a coach all paint and gilt, drawn by a team of oxen whose long horns are covered with nosegays and whose necks are decked with banners of rich brocade.

The procession is escorted by a cavalcade in the costumes of the ancient militia, and the coach is preceded by musicians playing launeddas. The ceremony takes place on the first of May and the saint comes back to Cagliari after sunset on the fourth,

Great efforts are being made to maintain these festivals unaltered, but the concourse of visitors from all parts of the island is not so great as it was some years ago. The once keen enthusiasm for these ancient customs, which are but a relic of the Spanish tule in Sardinia, has become lukewarm.

FEW HOTELS OR INNS

In a land that does not possess many hotels or inns, the system of receiving travelers is more than a custom; it is almost a law. Hospitality is one of the strongest traits of the Sardinjans. A stranger is always received with the utmost cordiality and sociability, everybody being anxious to do something to help him. Accustomed as the Sardinians are to solitude and silence, they fear that a person may feel too deeply the loneliness of traveling unknown in a country where villages are so far apart.

Sardinian hospitality has always been spoken of in the highest terms by authors and travelers. It has come down to us unchanged from the old Roman days, when the shrine of Jupiter Hospitalis was erected in every village and palace in the island.

THE GUEST, A SACRED PERSON, IS FORBIDDEN TO PAY

If you happen to reach a village on a feast day, you are never left alone. Somebody is sure to come and invite you to enter his house, to sit at his table, and to partake of his dinner. If you have a letter of introduction for some influential person of the place, you will receive an almost regal reception.

A foreigner who is unaccustomed to such treatment is reluctant to accept an invitation so freely offered. He wants to pay for every assistance he receives, but he cannot. He is forbidden, for the guest, as in the days gone by, is considered a sacred person, and even in towns where life is much the same as in any other part of the world, this sense of hospitality is not completely lost, but is made manifest in a thousand ways.

In some villages an inn, or something resembling an inn, is managed by a person who in most cases is not a native of the place. In such places a stranger is sometimes overcharged, though of course only from a Sardinian point of view. Perhaps they charge too much for the food they furnish; but one must consider that guests are so rare and expenses so heavy that the business is not a profitable one. If tourists and merchants would visit these places more frequently, inns and hotels would provide more of the comforts of modern life. But on this subject prospective visitors must not be deceived, Accommodations in Sardinian inns are not good, and in the whole island there are but few hotels.

Unless one is willing to sit at a low table in a room full of smoke, eat roast pig and rough bread and cheese from the family store, and drink strong wine which makes tears come to his eyes, he cannot possibly know Barbagia.

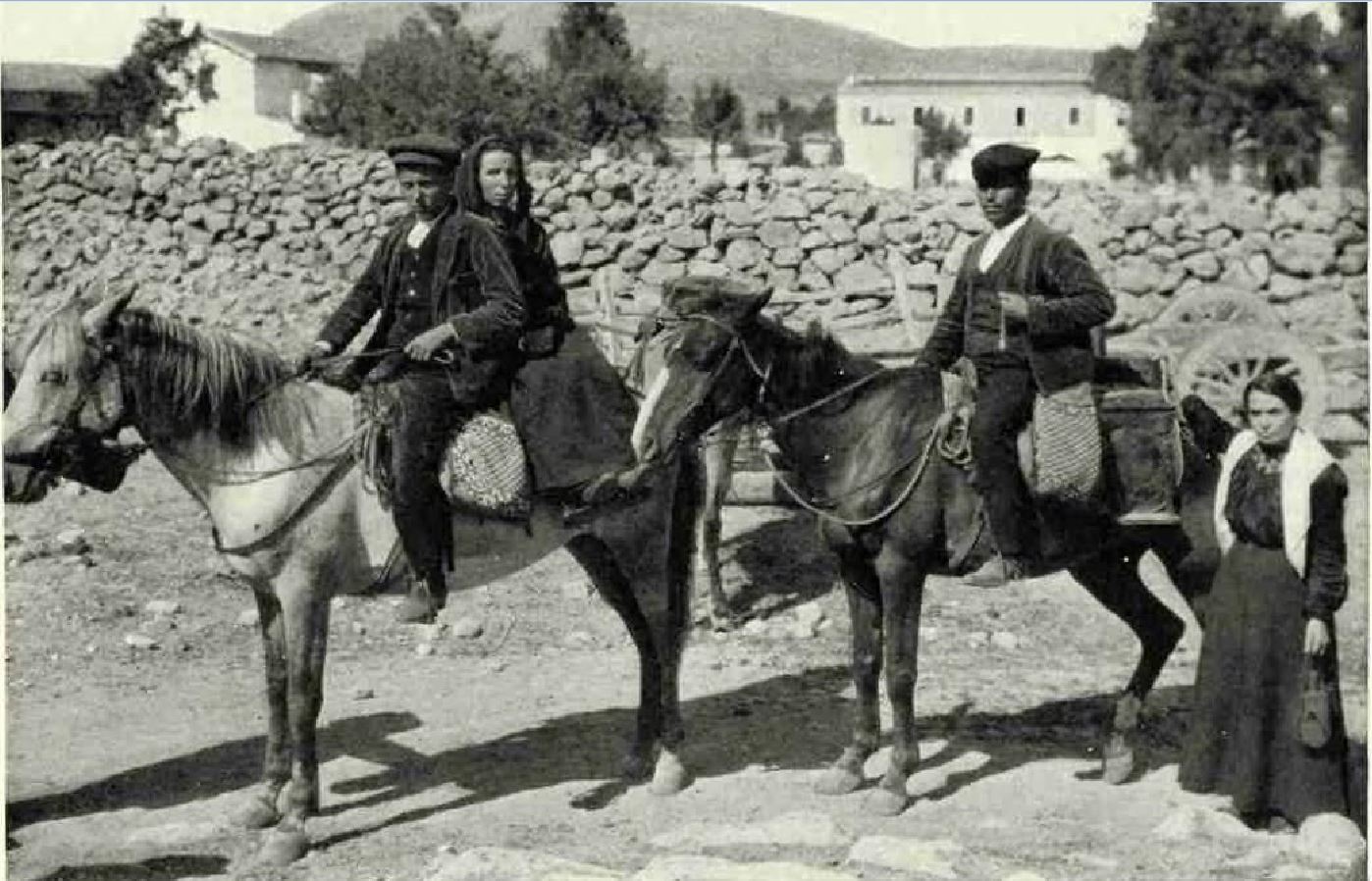

And until the traveler rides on one of those ponies that with steady step climb the mountain slopes along winding paths, seated astride a quaint Sardinian saddle with a saddlebag full to the brim of all the provisions for a long journey, and stops in the heart of a forest to see a kid roasted according to the Sardinian fashjon, he cannot know those wild landscapes which to know is to love.

MOST OF THE TRAVELING IN SARDINIA IS DONE ON HORSEBACK

The saddlebags, or bisaccia, made of coarse wool, are as much a part of the horseman’s equipment as is the saddle itself. In the background rises one of the nuraghi, those prehistoric ruins which dot the island.

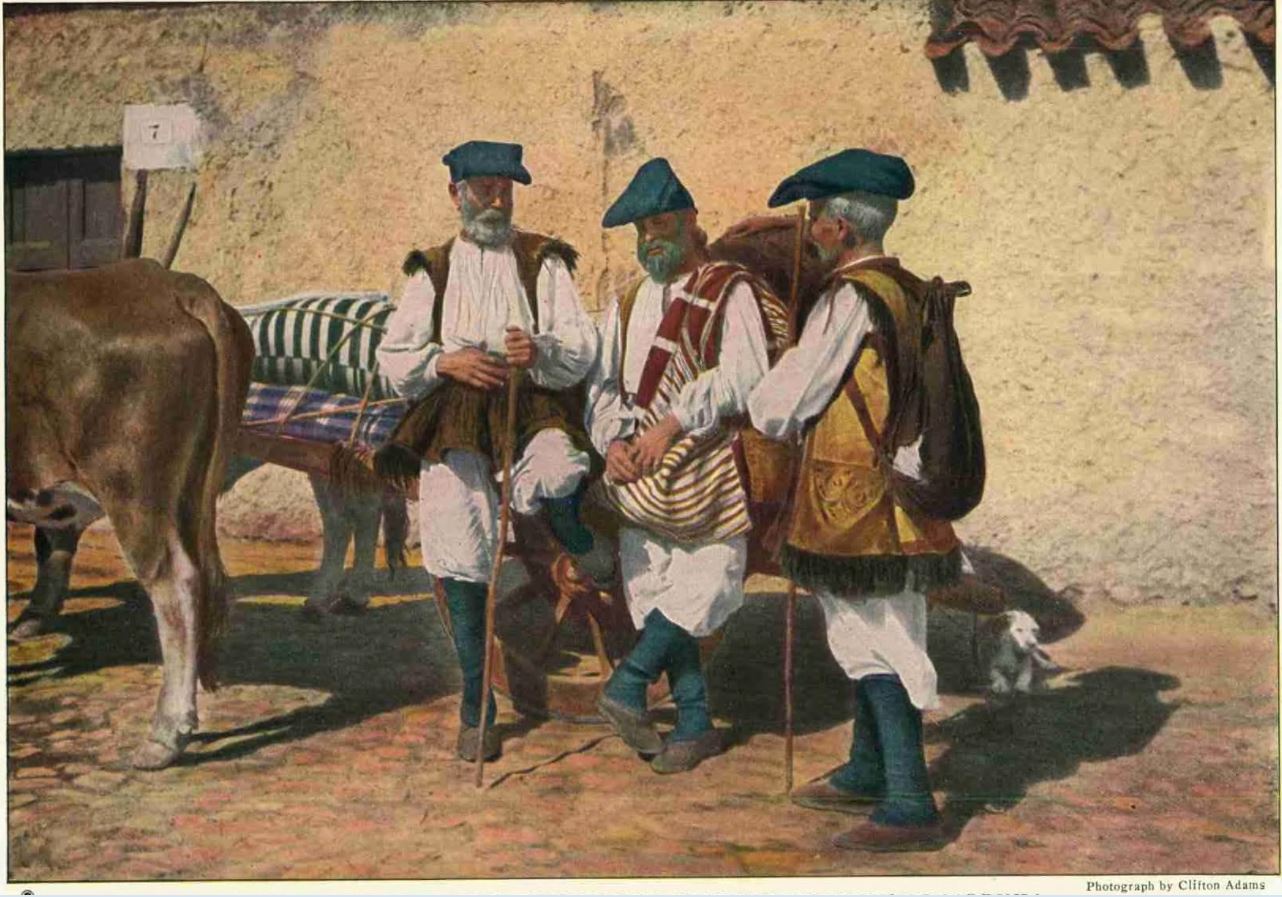

SARDINIAN PEASANTS COMING INTO MACOMER

As the horse is trained to carry double, the women ride behind the men. The saddles are works of art in leather of various colors, ornamented with bone buttons and pockets. There is always a little foot-board on the side for the riders’ feet.

A BARBAGIA MOUNTAIN WEDDING FEAST AT DESULO

The celebration lasts for several days and includes a feast for all the friends of the bride and bridegroom. The wine flows freely and the festivities continue far into the night.

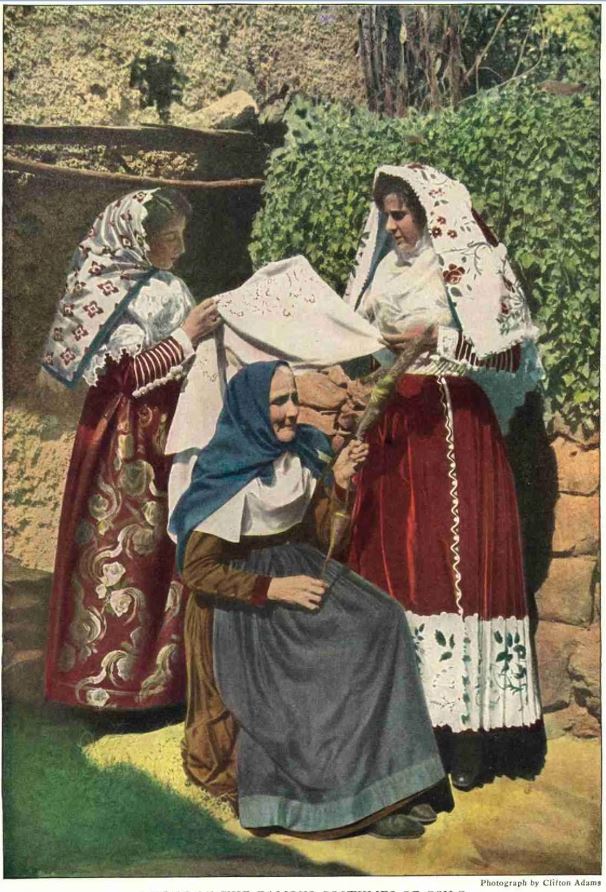

WHERE TO FIND THE RICHEST COSTUMES

An accurate description of the different articles which constitute a Sardinian woman’s costume would take pages. The most artistic are to be found in the northern districts. The women of Osilo wear the richest dresses in all the island. In Nuoro the women and girls retain the old fashions unaltered. At Oliena, Fonni, Desulo, and Aritzo the costumes vary greatly both in colors and pattern; but, sad to say, Sardinian costumes are rapidly disappearing. Eve body is anxious to dress in modern style. Young peasants have already put aside the male attire of former days and only the old villagers have any attachment for the costumes of their forefathers.

The costume of the women of Quarto Sant’Elena is described in every guidebook, but in vain would a visitor go to that large village in search of one. Only five or six specimens now exist and they are jealously kept in the bottoms of family chests, as souvenirs of a colorful past.

In Cagliari, for months and months no woman or man wearing a distinctive native costume is to be seen. Now and then, for some fancy ball or similar event, the elegant young ladies of Cagliari borrow costumes for a few days and wear them through the streets Everybody turns and looks with admiration at the unusual sight, to the amazement of foreigners, who on coming to Sardinia expect to find everyone in gay attire.

Artists and archeologists are thinking of founding in Cagliari an ethnographic museum containing specimens of the costumes of the various districts of Sardinia. Funds are already being raised for that purpose.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

A VILLAGE BEAUTY AT THE FOOT OF THE BRUNCU SPINA

This gorgeous costume of Aritzo is mostly of red coarse-woven wool. The trimming is green and blue and yellow, with silver braid on the shoulder, and the rich headcloth or scarf is of green and gold silk. The round-bottom apron is distinctive of the Barbagia region. From Aritzo one can climb the highest peak of the Gennargentu Mountains, which commands a superb view of sea and mountainous land.

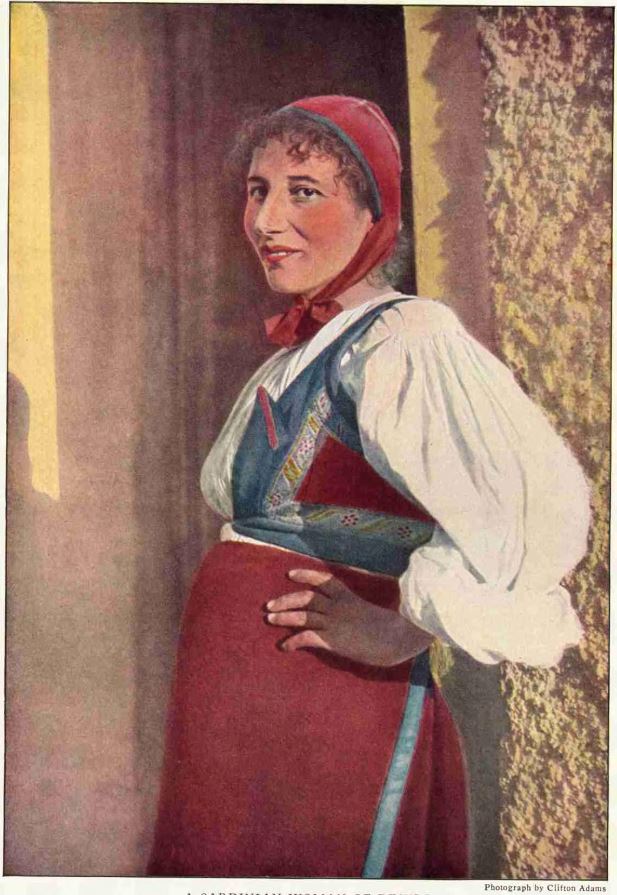

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

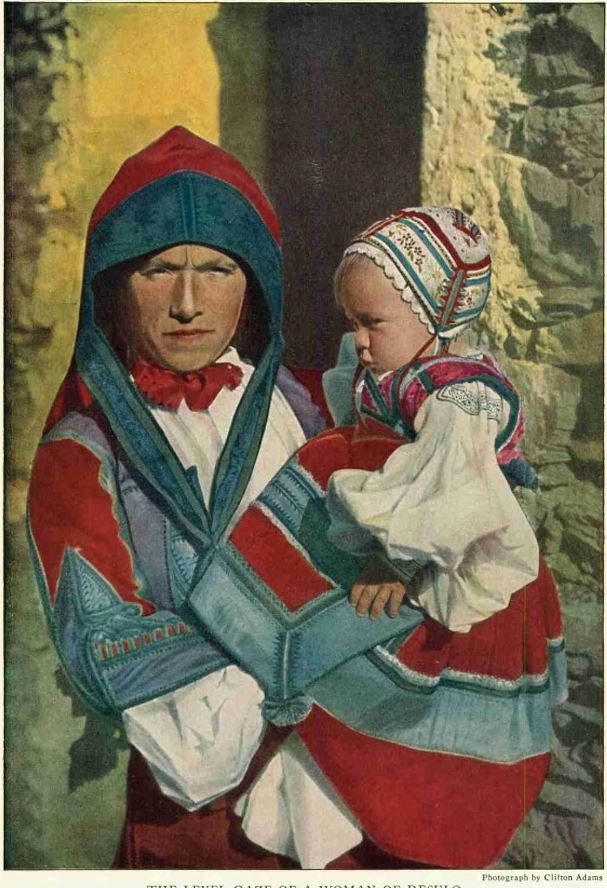

THE LEVEL GAZE OF A WOMAN OF DESULO

From childhood the women wear the distinctive costume of their village, and even the babies have the same bright colors. The peculiar tones of reds and blues in these costumes are typically Sardinian.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

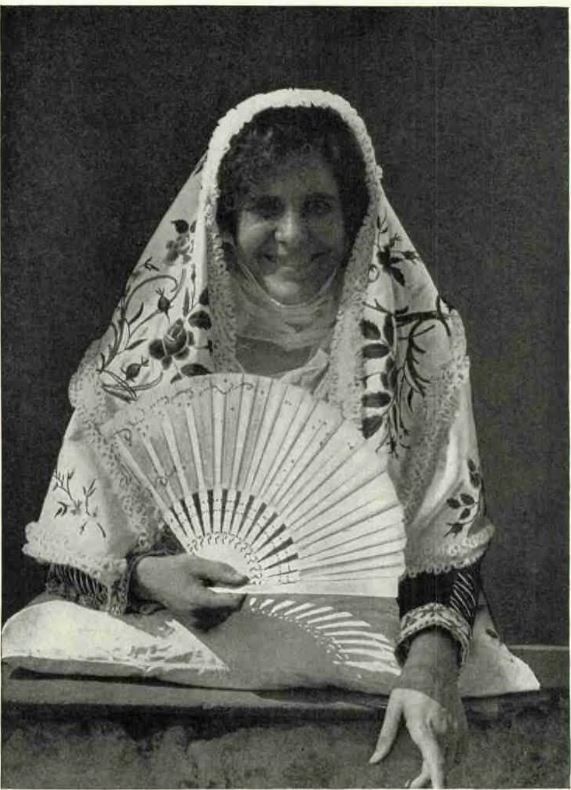

THREE OF THE FAMOUS COSTUMES OF OSILO

On each side are the gala costumes worn on Sun and féte days in Osilo. They are considered the most beautiful of northern Sardinia. The grandmothe son the dress which is ordinarily worn by old women throughout the island.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

A SARDINIAN WOMAN OF DESULO

Some Sardinians believe there was, generations ago, an admixture of Arab blood in these people whose village stands on the western slope of the Monti del Gennargentu. They have beautiful clear eyes, finely cut features and a proud bearing.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

A SARDINIAN GRANDFATHER

One knows it’s summertime because he wears his lambskin mastraca with the hair inside as a protection against malaria. There is a bite to eat in the end of his beretta, the long Sardinian cap which is worn the year round. This genial farmer lives in Macomer, a junction point where trains from four directions meet and spend the night.

COSTUMES NOW ‘100 EXPENSIVE FOR PEASANT BRIDES

Although costumes are a sort of family heirloom handed down from mother to daughter, they do not last forever. A modern bride cannot afford to have one made for her. Since the war the prices of brocade and silk have increased four or five fold and so have jewels. How can a peasant girl of Osilo, about to be married, afford $800 for a complete festival costume? She must content herself with a dress which, being designed after her own fancy, has lost the best features of the primitive costume.

Moreover, the farmers and rich peasants in the villages are wont to send their sons and daughters to the nearest town to attend secondary schools. When the boys and girls return home they will no longer wear native costumes, but want to be dressed in the latest European fashion. In Sardinian villages, even in the interior, you often see a mother, dressed in the most beautiful and gorgeous costume imaginable, walking beside her daughter, who is dressed according to the derniére mode of Paris.

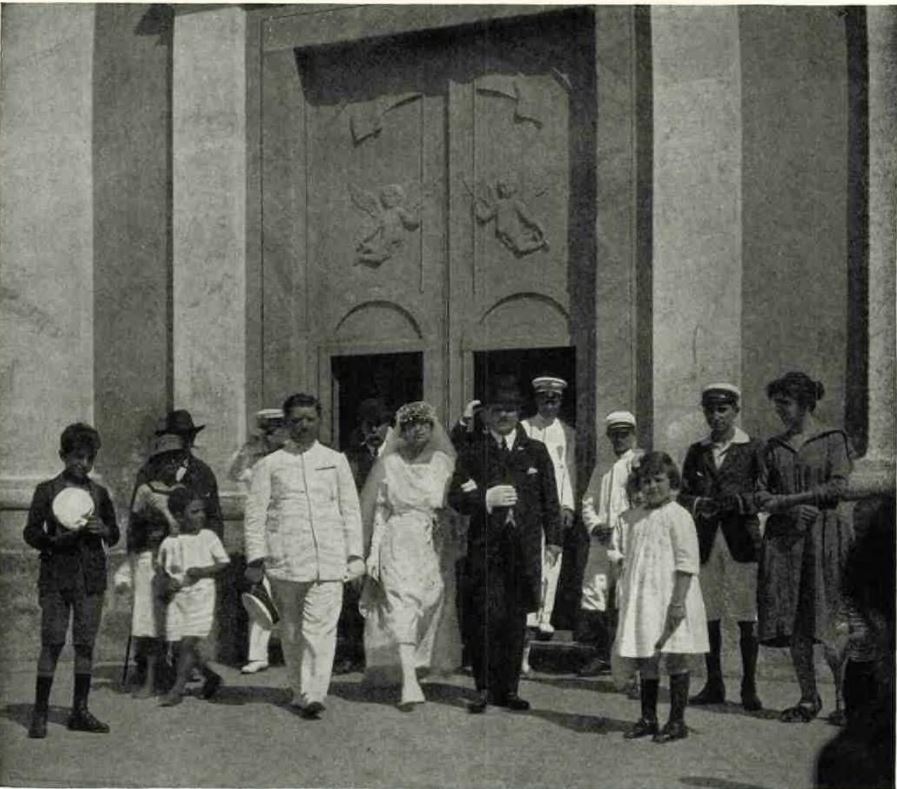

A CITY BRIDE AND BRIDEGROOM COMING FROM CHURCH

The duration of the ceremony is seldom more than five minutes.

Sometimes the daughter compels her mother to lay aside the fine old costumes and put on modern dress. The unhappy woman, not being accustomed to wear such inartistic modern hats, looks so awkward and embarrassed that she is very often laughed at and scorned by the townspeople and called a country cousin.

Authors have a lamentable fault — that of flattery through imitation. They are too often disposed to copy one another.

The wisdom of a past generation too frequently appears under new but inadequate disguise. Instead of describing what one sees and feels, which would be best, one is unconsciously tempted before visiting a place to read what some earlier visitor has said and felt about the same place, and thus pour fresh impressions into old molds.

Often authors come to Sardinia in a hurry, hire a motor car, run through the country at a speed of 30 miles an hour, and after a few days go back to the Continent and write a book about what they have seen. When they perceive that they have neglected an interesting place or missed a useful fact, they paraphrase what previous authors have written. Misstatements about Sardinia are therefore so numerous that they would, and do, fill many a book,

A legend too strongly rooted still persists about Sardinia as a land which cannot be conceived without its shepherds, wearing goatskin mantles; its large inclosures decked with asphodel; its women all dressed in the most gorgeous costumes, dancing and singing all the day long, and banditti at every house corner.

Many of these things still exist, but to discover them one must go to the interior of the island, in places situated far from the railways and highroads.

NEL COSTUME DI GALA DI OSILO

Sotto questo copricapo ricamato viene sempre indossato un sottile velo bianco.

IGLESIAS DISTRICT RICH IN MINES

A visit to Iglesias is interesting. The visitor finds himself in a Sardinia of which he has read nothing. Mines dot the region, tall chimneys streak the sky with smoke, machinery of all kinds makes the valleys echo with noise. The country is crossed by electric wires fixed to high iron towers, the main roads are traversed by a great number of modern vehicles, and in this district the old Sardinian cart is seldom seen.

This is industrial Sardinia, so little known abroad, which will have a great expansion when the reservoir of the Tirso is formed and electric current provided at a cheap price.

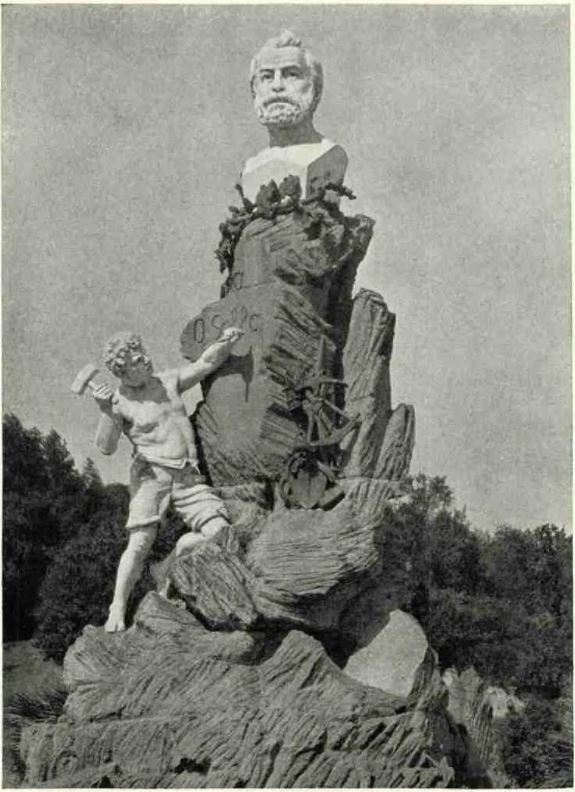

A STRIKING EXAMPLE OF SARDINIAN ART IN SCULPTURE

Sardinian monuments are usually of little interest, but this one to Quintino Sella, the pioneer miner, which stands in the Piazza Sella at Iglesias, is strikingly beautiful in its contrast of white marble and the

black volcanic rock of the region.

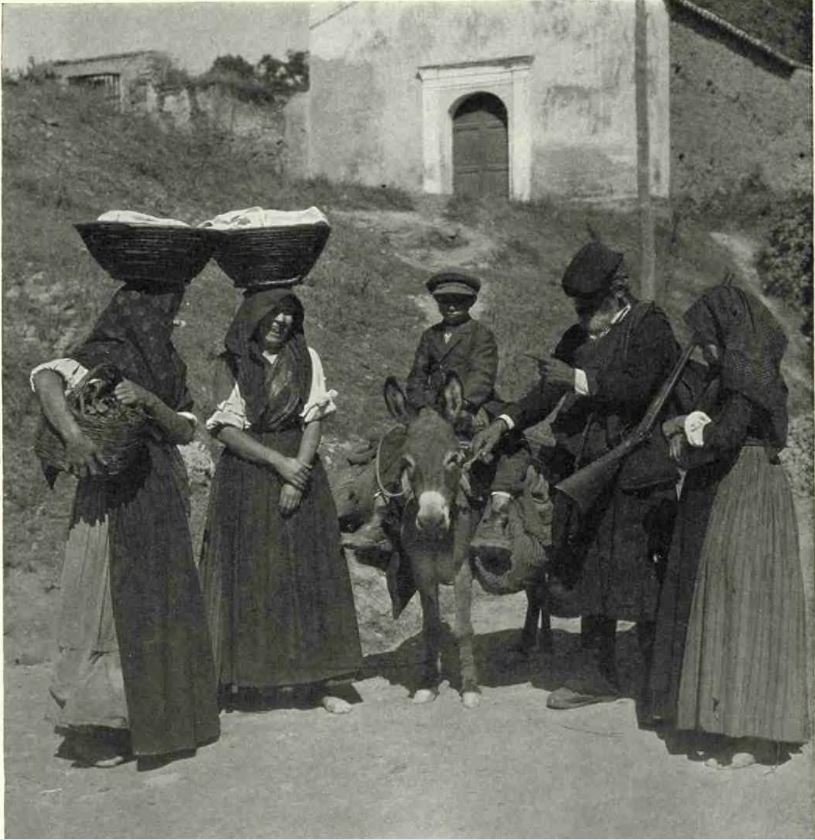

GENIAL PEASANTS OF THE IGLESIAS DISTRICT

The old man and woman are going to the country, but stop to visit and joke with the two women who are taking grapes to the town market and the boy who has two cans of milk in the saddlebags on his donkey.

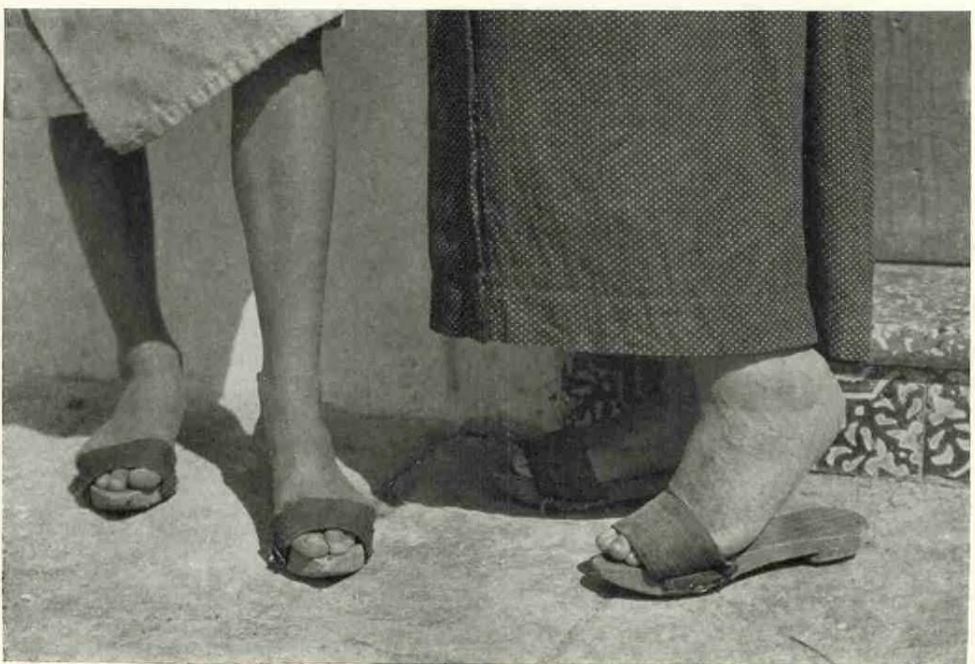

NO RUBBER HEELS IN SARDINIA

In the summer time the women and children of the Iglesias district go entirely barefoot or wear a rough plank of wood attached to the foot by a broad band of elastic across the toes. When walking in the streets of the villages, these sandals make a peculiar clacking noise on the stones.

SARDINIAN SMILES – Photograph by Clifton Adams

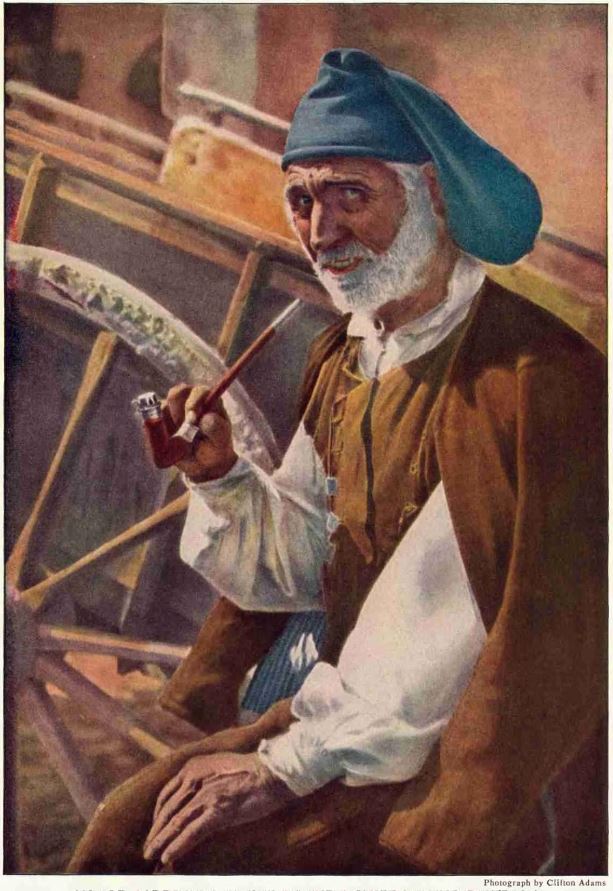

AN OLD SARDINIAN IN THE ISLAND’S CHIEF MINING DISTRICT

In Iglesias, a town of 10,000 inhabitants and the center of the Iglesiente, where lead and zinc are mined, the men wear their beretta, or long cap, a little shorter than do those of some other regions. Almost the entire costume is of heavy wool, the vest being fastened with large square silver buttons of antique design.

CAGLIARI

Cagliari has all the appearance of a modern continental city of the size of Pisa. Near the harbor, studded with steamers and sailing ships, a long, wide street lined with palaces looking out upon the sea, leads from the station to the Basilica of Buonaria. Upon this street open two broad thoroughfares, which, with a steep ascent, lead to the upper quarters (see illustration, page 2).

The town boasts terraces which command extensive and magnificent views. Whoever has walked for a while on the Bastione San Remy has received an indelible impression. From this elevated concourse the view of sea and land, of pools and meadows, is such that to live in Cagliari is to live upon a mountainside, perpetually refreshed by the exhilarating environment of space.

The town has monuments, elegant shops, theaters, bars, and clubs, a good school system, a university, and a public library.

During the summer months the favorite resort of Cagliari is a wonderful beach, with commodious bathing establishments, One part of it is called the Lido, in imitation of the celebrated Venetian strand, and many say that comparison is favorable to the Sardinian shor

In Cagliari a visitor is always interested in the medieval monuments. — Its towers, built by the Pisans about 1300, are standing in a state of perfect preservation (see page 6), and the gates to the Castello quarter, as well as the Cathedral, are worth visiting. In the same quarter is an archeological museum, with a hall dedicated to pre-Roman history, presenting a picture of prehistoric Sardinia, with its nuraghi, domus de gianas, and other relics of a hazy past.

THE TOWER OF THE ELEPHANT, ONE OF THE LANDMARKS OF CAGLIARI

This relic of medieval Pisan rule is in an lent state of ation, with its coat of arms, statuette of the elephant, and iron-bound portcullis text.

MANY MODERN INDUSTRIAL PLANTS

The town has industries, but they are quite modern and, of course, no guidebooks mention them. There is the chocolate manufactory, a factory for making cement, and a porcelain industry which promises a splendid future because of the excellent raw material in which Sardinia is rich.

Sassari, in its new quarters, is clean and lovely, and continental people prefer living there because it has an atmosphere comparable to that of the ordinary Italian town. This city also has industries, most important of which are tanneries that have already acquired renown in continental Italy and in France. From the olive groves surrounding the town the finest oil is produced and sold at high prices.

Tempio manufactures the products of its oak forests into cork (see illustrations, page 58), and in all Sardinia there is an awakening of industry and commerce which is encouraging.

Home industries are also thriving. At Bosa the women make very beautiful laces after old patterns, which are greatly appreciated not only in Sardinia but in Italy and abroad.

STACKS OF CORK-OAK BARK AT TEMPIO (front Aggius)

The gathering and export of this bark forms one of the principal industries of the northern region.

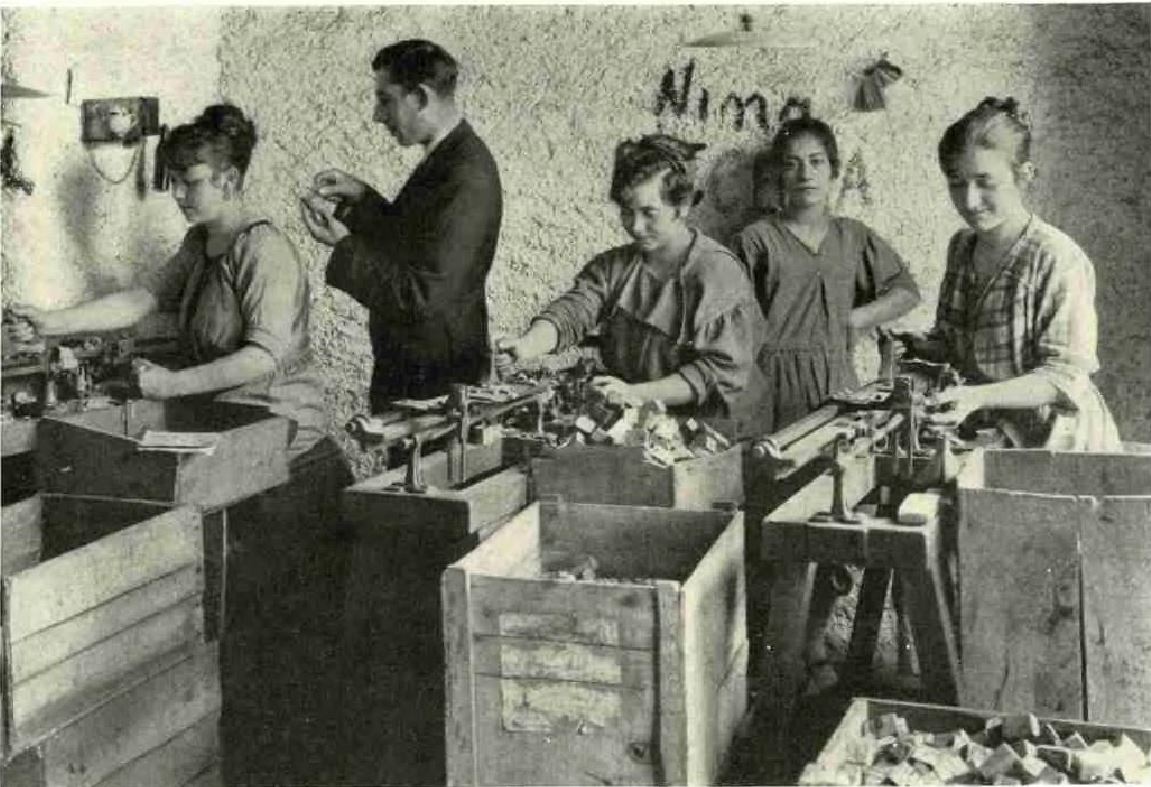

MAKING CORKS

Formerly corks for bottles were laboriously pared by hand, a dangerous process. To-day they are made by machines which whirl the square blocks of cork around a stationary knife.

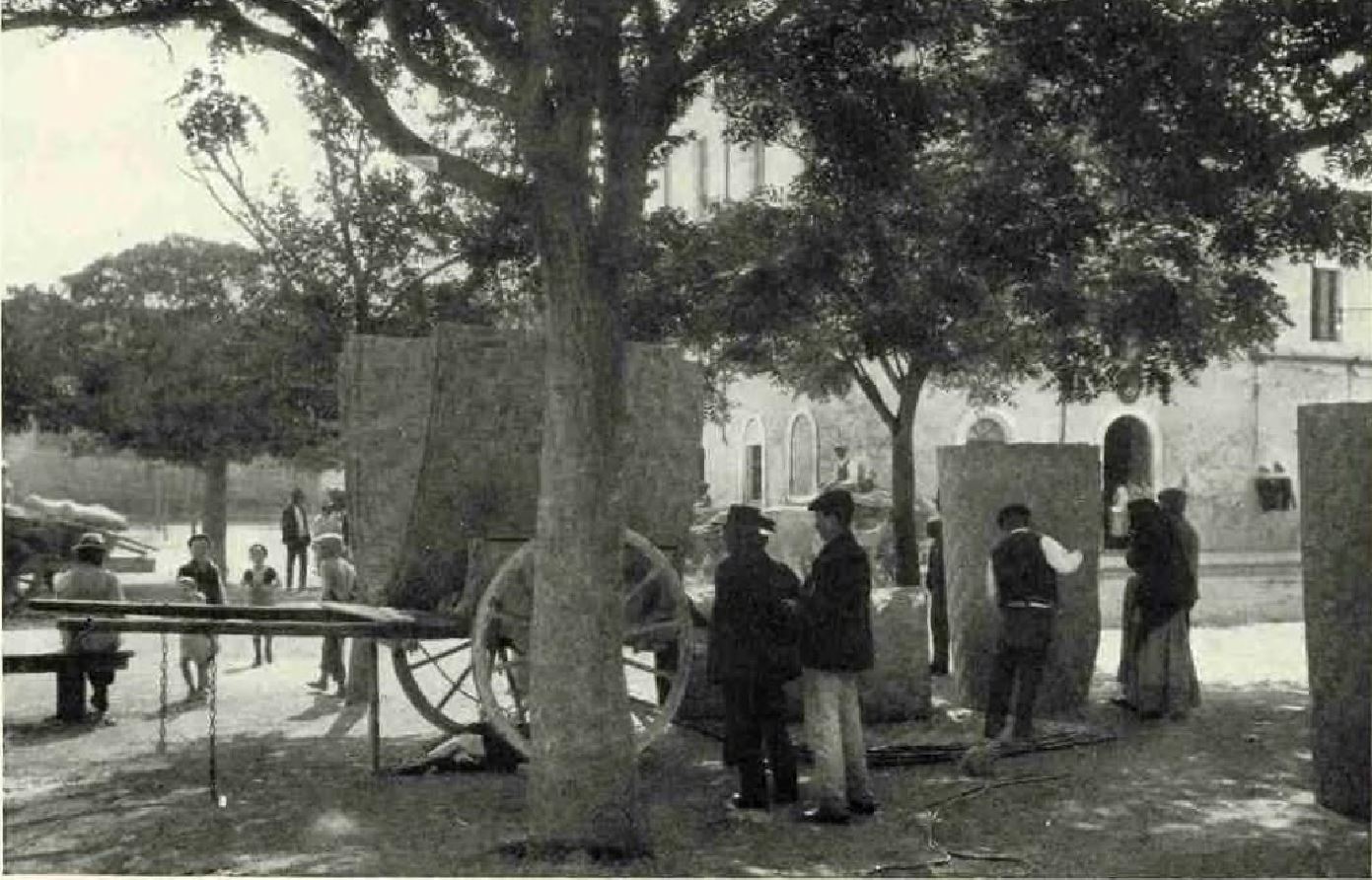

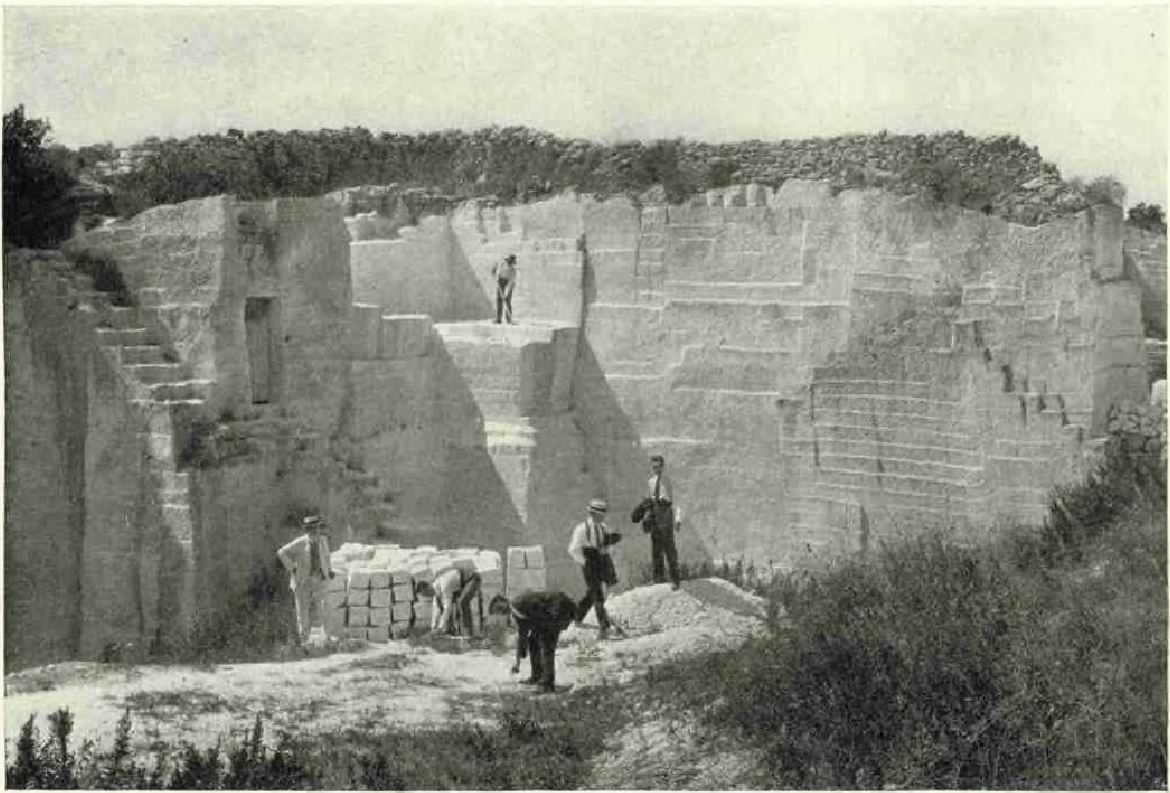

A ROCK QUARRY NEAR SASSARI