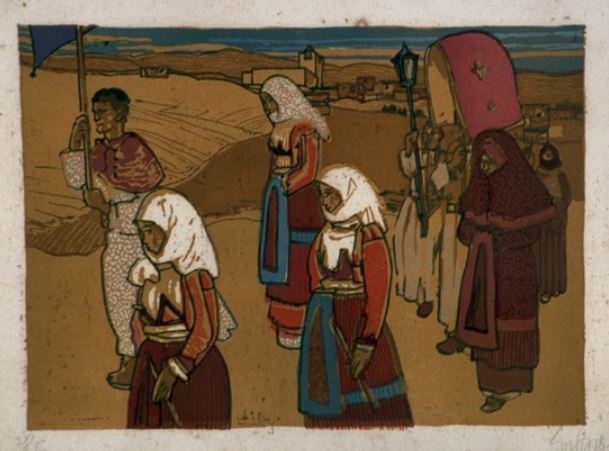

“In three days there will be the grand festa of Santa Maria di Arsequena,” said Best, addressing Campana- I, standing by, taking a survey of the muffled Moorish looking forms of the women, gliding along the dull little street of Tempio. “In three days, I say, and we cannot do this bandit country without attending it. Arsequena is twenty miles distant from this, seaward; it is a charming though a fatiguing ride, and we must have a military escort, which you can easily provide for us.” […]. We were amply repaid, however, when we reached our destination; a more singular, startling, and varied scene it would be difficult to witness.

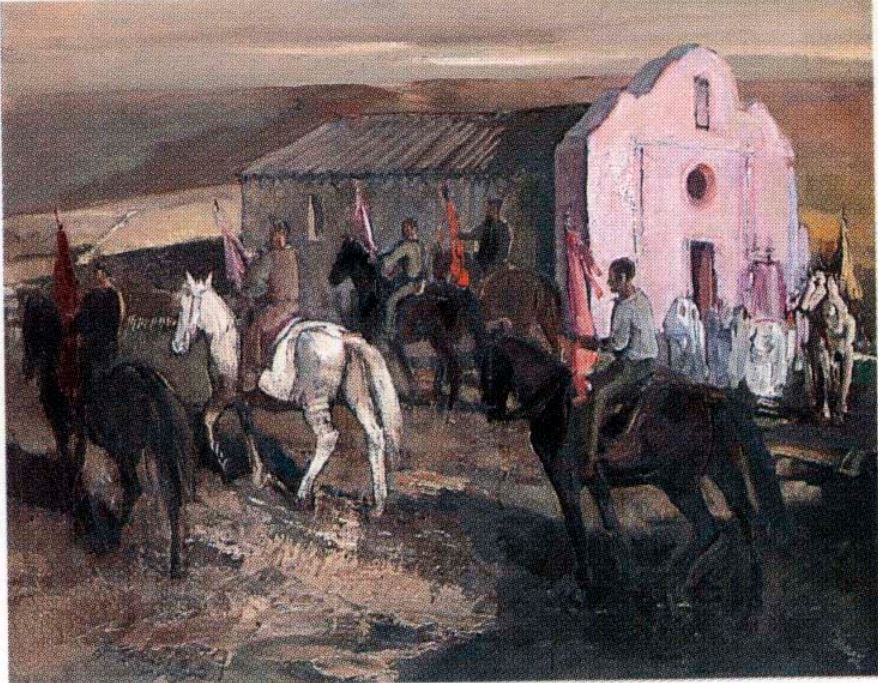

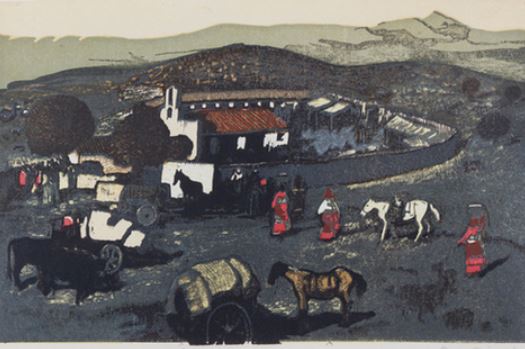

On a hill, partially covered with beautiful trees and shrubs, was perched the little chapel dedicated to “Santa Maria.” A large wooded plain stretched beneath, and this was full of busy life and bustle. Hundreds of horses were tethered in groups to the large trees around. In the distance might be seen “impromptu” abatoirs, where the processes of slaughtering and flaying were in active operation. There was no occasion to joint the animals, seeing that they were merely folded up in the leaves and branches of myrtle, and cooked whole, in deep holes in the ground, with charcoal embers under and over.

A very primitive cuisine this, and absolutely Celtic, but very excellent never theless, though possibly requiring some knowledge and skill as well as time and care. Best was quite au fait, he seemed deep in the mysteries of Sard cookery, and showed me the dish, par excellence, of the country. It was a monstrous wild boar, within which had been placed a kid; within the kid a sucking pig; and again within the sucking pig some dainty little birds. The fuming savoury amass was being disinterred at the moment of our visit to the spot set aside for the business of cooking, and, dear me! what boiling and baking, frying, and stewing there was, for I dare not say how many guests.

A long tract of ground was covered with rushes, myrtle, and lentiscus boughs, or the scilla marittima, to the height of five or six inches. This was to serve as a table for the vast multitude. The directors of this rustic festival, called the “Soprastanti,” were the “Capo Pastori,” or head shepherds of the district. These were forty in number, and for their share had contributed a sheep or a goat, thirty pounds of bread, twelve pounds of cheese, and, collectively, I dare not say how many hundred gallons of wine; several casks of oil, huge quantities of maccaroni, fruits, vegetables, confetti, fuel, and cooking utensils.

The upper portions of this vast banqueting table were covered with snowy napkins, and these places of honour were for the “Soprastanti,” and any whom they might invite to share that honour. Best and I were hailed with clamorous delight; Campana with deference and courtesy, but with a shade more reserve.

Our party were enthroned in state under a canopy of “cabanneddus” (great coats), stretched from bough to bough, and entreated to take a little wine and bread as a refreshment until the banquet should be served. Best was considered an important auxiliary, and was continually consulted. Would the “Signor Ufficiale” (officer) like this, or the “Milordo Inglese” enjoy that? Do they have it so in their country?

Bertoldo, too, was in the very zenith of importance and popularity. It was intensely amusing to see his condescension; he was evidently considered as a man of unusual experiences. At a given signal, the smoking viands were placed in their envelopes of leaves on the monstrous leafy table; sheep, deer, goats, sucking pigs, fowls, kids, wild hogs at intervals, with the complicated national dish at the top; then tubs of maccaroni cooked with cheese and gravy, miniature mountains of fruits, cher ries, early grapes, figs, and the like. Branches of myrtle served for plates, daggers for knives, twigs of pronged myrtle for forks. The feasting began in right earnest, and Sards are by no means contemptible gourmands. Hilarity scarce knew any bounds; the clatter was universal.

The Soprastanti insisted on waiting upon us; we were to have the daintiest morsels, the most delicate wines, the softest seats. There were knots of dark-eyed women and bronzed little children grouped about variously under the beautiful trees, feasting, chatting, and sleeping.

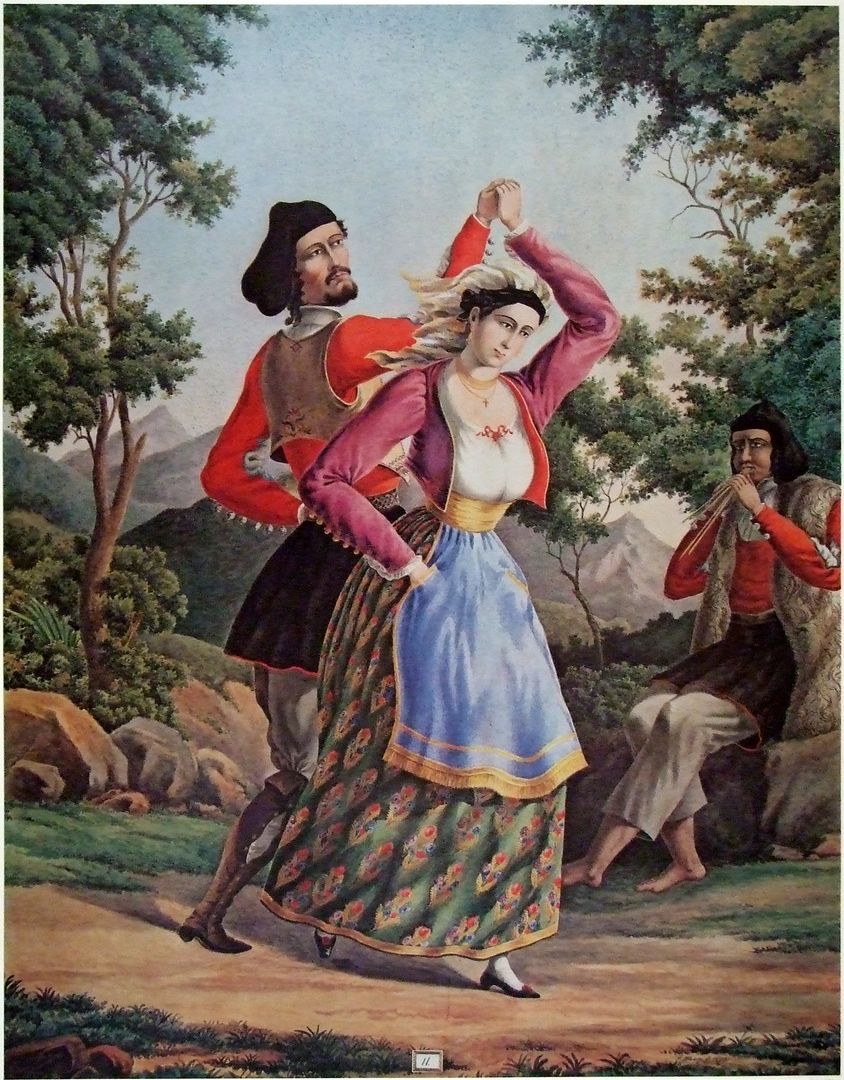

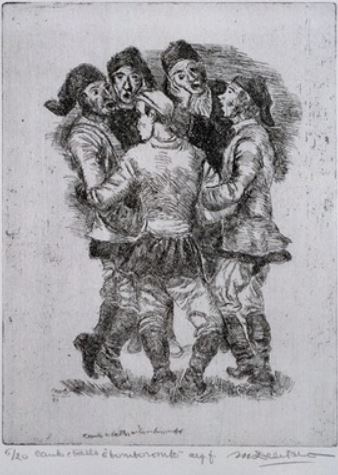

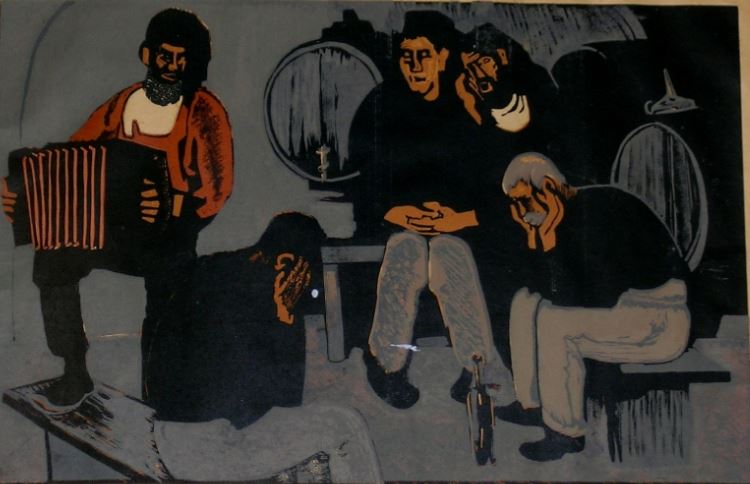

By-and-by amusements began. The ballo-tondo, as a matter of course, commenced its sinuous maze. This was varied by more lively dances known as the “Policordina” and the “Salto Sardo.” Poets were reciting in a coarse recitative; orators haranguing; tale-tellers declaiming; gleemen singing.

The shadows lengthened, the sun set, the “Ave Maria” pealed from the little chapel on the hill-every head bent, every lip moved in prayer.

The festivities again were resumed, and the dancing and tale-telling were going on far into the night, as the bright stars peeped out from the deep purple of a cloudless sky, so clear, so bright, the only canopy over that vast multitude.

The festivities again were resumed, and the dancing and tale-telling were going on far into the night, as the bright stars peeped out from the deep purple of a cloudless sky, so clear, so bright, the only canopy over that vast multitude.

Groups here, groups there; nay, whole families with their little ones were curled up in their cabbanneddus under the trees, fast asleep.

Some lively spirits seemed inexhaustible, and It was the monotonous whirr of confused sounds gradually became mingled with a snore. Campana, who, wrapped in a cabbanneddu, the hood over his head, was in a deep slumber. Best and I soon followed the example, and we lost all knowledge of our whereabouts, snugly reclining on a heap of leaves beneath a cork tree. My sleep was not so unbroken as theirs; the novelty of the whole scene had so taken hold of my imagination, that I started up from time to time with a bound. I suppose other nerves were similarly acted upon, for I heard glee-singing in the distance-a never tiring poet reciting his endless verses; and what was far more delightful, the song of innumerable nightingales, which people this pretty, but generally lonely valley. […]

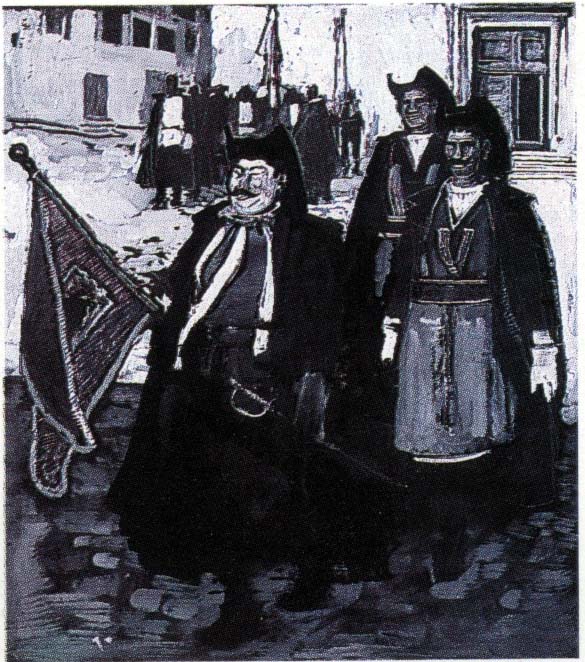

The little bell of the rustic chapel pealed out the morning offices. The sun rose in the heavens, and the vast multitude in that vale of Arsequena, was again on the alert. A grand procession of the various orders of ecclesiastics now began to appear, bringing with them The Sacred Banner of Tempio surmounted by a cross. This was formally planted in the centre of the open space at the foot of the hill on which the chapel was perched. Its richly embroidered folds were waving heavily in the soft morning breeze, amid the “aves” and “paters” of the people.

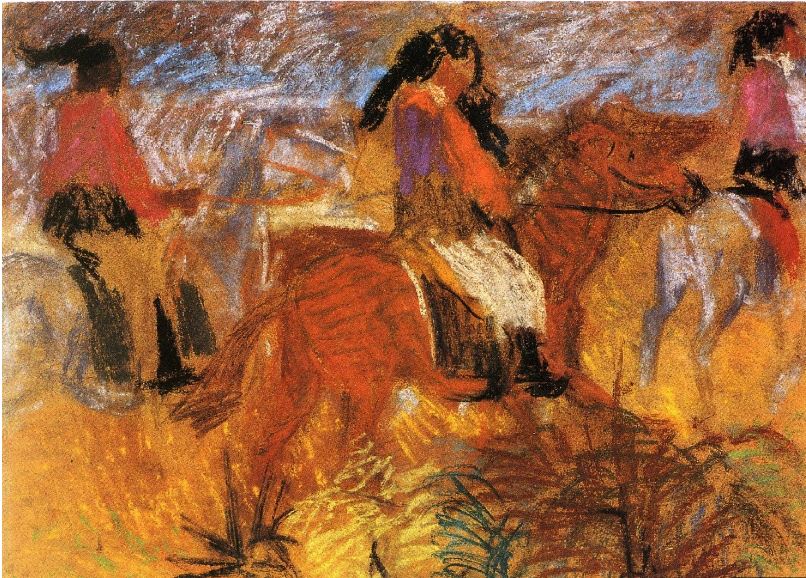

This over, amusements recommenced with double force, for it was Sunday, and the grand day of the festa. So as I said, after the service, amusements for a time recommenced, not the dancing, but horse racing, and horse racing of the most primitive kind. Several beautiful horses were brought out to display their speed, they were mounted by lithe, bronzed, half clad, wild looking young fellows, carelessly reclining on their unsaddled backs, their long locks streaming over their reeking flanks. On they went over tangled brushwood, shrubs, and stones, as though they were glued to their backs.

This over, a handsome youth, of a noble family, presented himself. He was mounted on a magnificent roan. The sacred banner of Tempio was cere moniously presented to him, and, taking it in his hands, he bore it up the hill, then taking the direction of the sun, he took it three times round the chapel, the people prostrating themselves to the ground, catching hold of it, and devoutly kissing it in its progress. There was grace, devotion, and faith in the act, blind, superstitious, and idolatrous as it was, for the youth acted out his part after a princely fashion. He belonged to a noble family of the Gallura, and the privilege of bearing that banner up that hill had belonged to his race for countless generations.

After certain other religious services, the dancing, reciting, and tale-telling recommenced, then the dinner, the siesta, the dancing, and the supper, exactly as before.

On the Monday morning the whole multitude proceeded a little way in another direction, where was a ruinous chapel dedicated to “San Pietro di Baldolino” where for that day again the ceremonies, feasting, and festivities, were to be continued.

Best was not disposed to go to this said chapel of “San Pietro di Baldolino.” It was, he said, a sort of charnel house of the shepherds of the vicinity; the bodies were thrown rudely into a large vault, and the atmosphere in the immediate neighbourhood was poisoned by its exhalations. The Soprastanti had caused an altar to be erected outside the wretched building, but, even so, he by no means inclined to join the pilgrimage.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs (captions translated freely)

by Giuseppe Biasi, from the website Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Mario Delitala, from the website Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Antonio Ballero, from the website Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Giovanni Marghinotti, from the website Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Stanis Dessy, from the website Catalogo Beni Culturali

by Pietro Antonio Manca, from the website Catalogo Beni Culturali

Postcards and Photos

coll. Francesco Cossu

Contemporary Photos

by Gallura Tour, Hans Leysieffer

© RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA