LA MADDALENA

by John Warre Tyndale

The Island of Sardinia

London 1849

Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street

Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty

in italian: ![]()

The first object that strikes the stranger on his arrival is the excessive cleanliness. The Spaniards call Cadiz “La Jicara aurea de España”, and La Madalena may be christened with equal justice, “The Golden Cup of Sardinia.” The quays are in good order, and the generality of the houses being built of granite, or white-washed, have a solid and neat appearance. The population amounts to about 2300, two-thirds of whom are engaged in the coasting-trade.

The Ilvese women, though industrious in their domestic occupations, have little employment beyond making nets and working the nachera. Almost every house has a mill, and the women not only make the bread, but grind the corn. Some time since it was proposed to save this female drudgery by establishing windmills, and no difficulty existed in the means and locality; but the proposition was overruled, as it was considered that if the employment were taken away from the women, they would be perfectly idle.

The Ilvese area distinct race from the Sardes. Until the year 1767, when Carlo Emanuele III took formal possession of this as well as of the adjacent islands, it had been inhabited by native and Corsican nomad shepherds who, by their constant communication with Corsica and Sardinia, and by intermarriage with the natives of both, were considered as a “mezzo termine” mentally and physically, as they were territorially.

The port called Calagavetta, might be good, but owing to an accumulation of sand and dirt, is incapable of holding vessels of more than 400 tons.

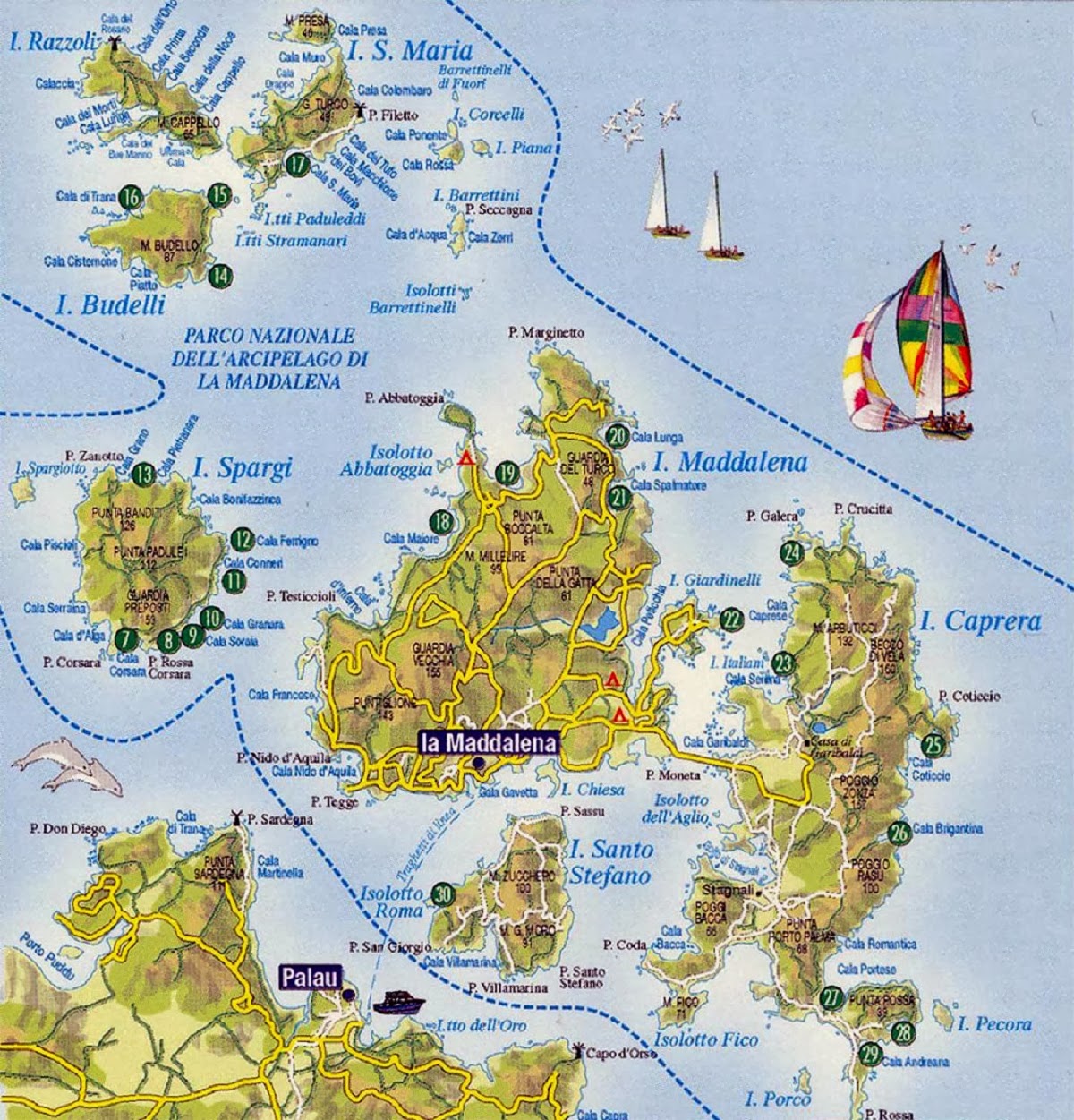

It is sheltered by the hills of the island on the north and north-east, by the island of Caprera on the east, by St. Stefano to the south, the head-lands of the Sardinian shore break the force of the westerly gales, and the fortresses of St. Vittorio, St. Agostino, St. Teresa, Balbiano, St. Andrea, and St. Georgio, are so placed as to be able to pour a cross-fire on any vessel which might attack the port.

That of St. Vittorio overhanging the town on a steep eminence of 600 feet, commands an extensive view over the Polynesia of the north-west of Sardinia, and south and south-east coast of Corsica.

The principal and parochial church, dedicated to La Madalena, was built with granite and marble, from the islands of La Testa and Tavolara; the greater part having been brought by the natives on their dies fasti, as religious vows and offerings, according to the custom in many Roman Catholic countries. It is very neat and in good taste; but the other church, built in 1764, about two miles from the town, has nothing worthy of remark.

The climate is healthy, intemperie and pleurisy being unknown; and the majority of the inhabitants attain a considerable age.

The trade, consisting in the exportation and freight of corn, cattle, and cheese, to Bastia, Leghorn, and Marseilles, is carried on by about twenty-two vessels of twenty tons each, and seventy of a smaller class for coasting. 262 vessels, exclusive of ships of war, entered the port during 1842; of which 191 were Genoese, 55 Neapolitan, 14 French, and 2 Tuscan; their united tonnage being 4825. […]

On the 22nd of February 1793, a French blockading force, consisting of a large frigate and several smaller vessels, under the command of General Cesari, left Bonifacio, and, landing in the night on the Island of St. Stefano, disembarked their material and raised a battery, the vessels taking up their position between the two islands.

On the 24th, Buonaparte, who was second in command of a company of Corsican artillery, under Colonel Giambatista, at St. Stefano, opened a heavy fire on La Madalena, and it was responded to with equal fury and vigor from a battery which the islanders had raised. Their garrison amounted to five hundred; and the Gallura shores were defended by its native mountaineers, who rallied around their holy banner of La Madonna di Logu Santu.

The French frigate having been dismasted bore up for Arsachena; and the passage between the islands being thus clear, a force of 400 Sardes embarked from Parao and attacked St. Stefano. So vigorous was the onset that Buonaparte was obliged to escape precipitately with some of his party from the island, leaving 200 prisoners, with all their stores, baggage, and artillery; and in passing between the other islands they were also attacked by some Gallurese who had concealed themselves off Capo della Caprera, and who, by the precision of their firing, committed great havoc among the flying enemy. Many of the Corsicans and Ilvese who witnessed this action are still living; and they narrate various circumstances relative to it.

While in garrison at Bonifacio, as lieutenant of artillery, he had mortar and gun practice every Sunday, and on all occasions had shewn the greatest precision in firing. In this particular instance he was no less successful, for the bomb entered the church window, and fell at the foot of the image of N. S. di Madalena. It refused to burst in its presence, and this miraculous instance of politeness and religious respect had its due weight with the pious islanders, by whom it was taken up, and for a long time preserved among the sacred curiosities of the town, till a gentle man bought it for 150 francs, and, it is said, sent it to Scotland. A natural cause was, however, soon found for the harmlessness of the projectile.

In October, 1803, he proceeded with his fleet to this, his favorite spot, and notwithstanding a heavy gale of wind, in addition to the usual dangers of the Straits of Bonifacio from the number of islets and sunken rocks, he reached his destination in safety. The exact words of his diary need not be quoted, as they are only interesting in a nautical point of view; but in a letter to Captain Ryves, dated November 1st, 1803, he says: “We anchored in Agincourt sound yesterday evening… We worked the “Victory” every foot of the way from Asinara to this anchorage, blowing hard from Longo Sardo, under double-reefed topsails. This is absolutely one of the finest harbours I have ever seen!” The difficulties of the Bonifacio passage can hardly be understood by the landsman, but they are stated to have been so great, “and the ships to have passed in so extraordinary a manner, that their captains could only consider it as a Providential interposition in favor of the great officer who commanded them.”

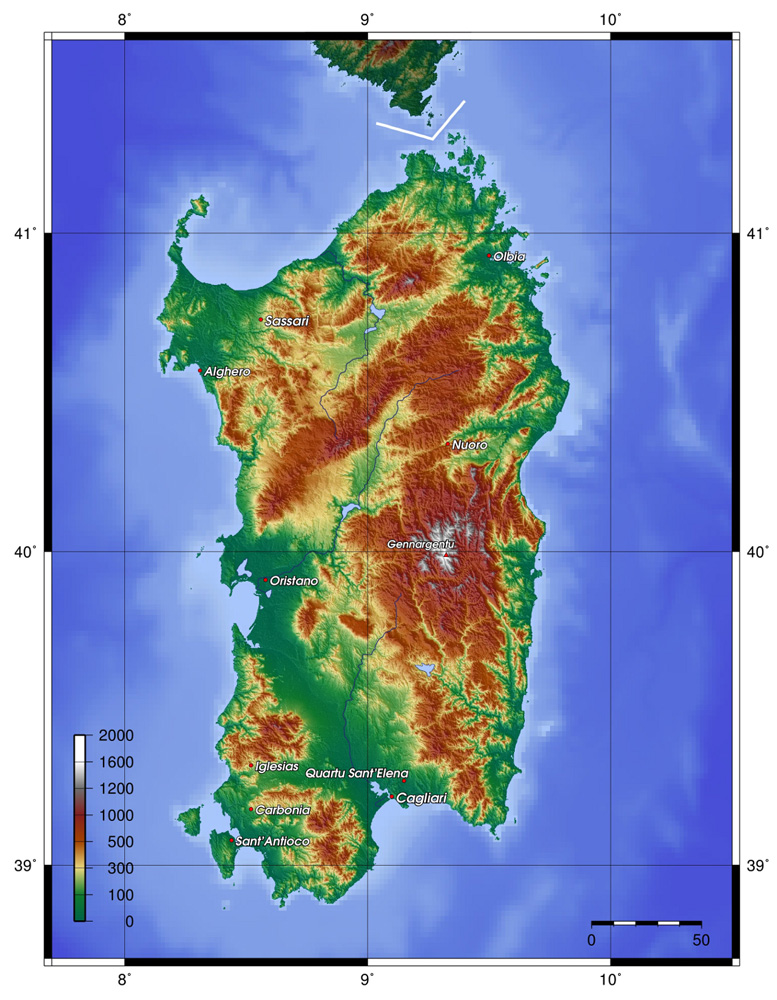

The following letter to Lord Hobart, dated December 22nd, 1803, shews how forcibly Lord Nelson impressed the importance of the island on the British government: – “My dear Lord, In presuming to give my opinion on any subject, I venture not at infallibility, and more particular information may convince me that opinion is wrong. But as my observations on what I see are not unacceptable, I shall state them as they strike me at the moment of writing. God knows if we could possess one island, Sardinia, we should want neither Malta nor any other. This, which is the finest island in the Mediterranean, possesses harbours fit for arsenals, and of a capacity to hold our navy within twenty-four hours’ sail of Toulon, bays to ride our fleets in, and to watch both Italy and Toulon; no fleet could pass to the eastward between Sicily and the coast of Barbary, nor through the Faro of Messina.

“Malta, in point of position, is not to be named in the same year with Sardinia.

All the fine ports of Sicily are situated on the eastern side of the island: consequently of no use to watch anything but the Faro of Messina. And, my lord, I venture to predict that if we do not, from delicacy or commiseration of the lot of the unfortunate King of Sardinia, the French will get possession of that island.

Sardinia is very little known: it was the policy of Piedmont to keep it in the background; and whoever it has belonged to, it seems to have been their maxim to rule the inhabitants with severity, in loading its produce with such duties as prevented their growth. I will only mention one circumstance as a proof. Half a cheese was seized because a poor man was selling it to our boats, and it had not paid the duty. Fowls, eggs, beef, and every article are most heavily taxed. The coast of Sardinia certainly wants every penny to maintain itself; and yet I am told, after the wretched establishment of the island is paid, that the king does not receive 5000 l. a year.

The country is fruitful beyond idea, and abounds in cattle, sheep, and would in corn, wine, and oil. It has no manufactories. In the hands of a liberal government, and freed from the dread of the Barbary states, there is no telling what its produce would not amount to. It is worth any money to obtain, and I pledge my existence it could be held for as little as Malta in its establishment, and produce a larger revenue”. The remainder of this despatch is respecting other matters.

He thus writes to Mr. Jackson on February 10th, 1804. “The storm is brewing, and there can be little doubt that Sardinia is one of the first objects of its violence. We have a report that the visit of Lucien Buonaparte is to effect an amicable exchange of Sardinia for Parma and Piacenza. This must not take place, or Sicily, Malta, Egypt, &c. &c. &c. are lost sooner or later. What I can do to ward off the blow shall be done, as I have already assured H. R. H. the Viceroy. From Marseilles to Nice there are not less than 80,000 men ready for embarkation. Should Russia go to war with France, from that moment I consider the mask as being thrown off, with respect to any neutrality of his Sardinian Majesty. Therefore, if that should be the case, would the king consent to two or three hundred British troops taking post upon Madalena. It would be a momentary check against an invasion from Corsica, and would enable us to assist the northern part of Sardinia. You will touch upon the matter in the way you think most prudent, or entirely omit it; but there is only this choice, to lose the whole of Sardinia, or allow a small body of friendly troops to hold a part at the northern end of the island. We may prevent, but cannot re-take.

Sardinia is the most important post in the Mediterranean. The wind which would carry a French fleet to the westward is fair from Sardinia; and Madalena is the most important station in this most important island. I am told that the revenue, after paying the expenses of the island, does not give the king 5000 l. sterling a year. If it be so, I would give him 500,000 l;. to cede it, which would produce him 25,000 l. a year for ever. This is only my conviction; but the king cannot long hold Sardinia.”

To Lord Hobart, he says (March 17, 1804), “It is the summum bonum of every thing which is valuable for us in the Mediterranean. The more I know of it, the more I am convinced of its inestimable value, from position, naval port, and resources of all kinds.”

The following is from a letter to Lord Hawkesbury, dated June 22, 1804. “If I were at your Lordship’s elbow, I think I could say so much upon the subject of Sardinia, that attempts would be made to obtain it. For this I hold as clear, that the King of Sardinia cannot keep it; and if he could, that it is of no use to him. That if France gets it, she commands the Mediterranean; and that by us it would be kept at a much smaller expense than Malta. From its position it is worth fifty Maltas.”

There are various other letters of Lord Nelson on this subject, but sufficient have been adduced to shew the high estimation in which he held the island.

While at anchor at La Madalena and in Agincourt sound, he kept two or three vessels continually cruising between Toulon and the straits of Bonifacio, to signalize to him in case any of the enemy should attempt to come out of that port, occasionally taking the whole fleet with him on a cruise, and then returning to his head quarters. It was from this sudden presence and disappearance of his vessels off Toulon, in his endeavour to allure the French fleet out, that Monsieur Latouche Treville, their admiral, made his ludicrous and well-known boast “that he had chased the whole British fleet, which had fled before him”. This false assertion so irritated Lord Nelson that he constantly alluded to it in his dispatches to the government, as well as in his private conversation and letters; and in one of the latter to his brother, he says, “You will have seen by Latouche’s letter how he chased me, and how I ran. I keep it; and if I take him, by God he shall eat it.”

On the 19th of January, 1805, the vessel in the offing signalized that the French fleet had put to sea; the accomplishment of all his expectations, wishes, prayers, and vows. One of my informants at La Madalena mentioned to me that there was much gaiety in dances, private theatricals, and other amusements, on board the different vessels at that period, and it so happened that a rehearsal, or some preparation for the evening’s entertainment, was going forward at the moment the all-stirring signal was discovered.

As soon as it was acknowledged on board the Victory, the responding one appeared, “under-weigh immediately;” and the scene of excitement and confusion from the precipitous departure and interruption of their festivities was most graphically narrated. It was a dark wintry evening, and the quickness of the order was equalled by the skill and courage with which it was executed. The passage is so narrow that only one ship could pass at a time, and each was guided merely by the stem lights of the preceding vessel. At seven o’clock the whole of the fleet was entirely clear of the passage, and bidding a long farewell to La Madalena, they stood out after the French fleet to the southward. Though Lord Nelson only slightly alludes to it in his diary, yet the extreme hardihood and determined spirit exhibited by him on this particular occasion was the subject of especial eulogy in the House of Lords by his late Majesty, then Duke of Clarence, being cited as the greatest instance of his unflinching courage and constant activity. It has been stated also by those acquainted with the locality, and consequently with the difficulty of the task, to be no less a proof of his skill and tactics.

More than one motive is attributed to Lord Nelson in this gift, though generally ascribed to his acknowledgment of the kindness and hospitality he received from the islanders. When the town publicly thanked him for the donation, he replied, according to my informant’s statement: – “These little ornaments are nothing. Wait till I catch the French outride their port. If they will but come out I am sure to capture them; and I promise to give you the value of one of their frigates to build a church with. I have only to ask you to pray to La Santissima Madonna, that the French fleet may come out of Toulon. Do you pray to her for that, and as for capturing them I will undertake to do all the rest.”

A bit of scandal, current at La Madalena, may be mentioned, for the purpose of endeavouring to refute it. Notwithstanding the liaison of a Hamilton it is asserted, and is in print, that Lord Nelson was not insensible to the charms and blandishments of a young and lovely girl, who was at that time considered the belle of the island. Emma Liona, for such was her name, was no less flattered by his attentions; and the consequent amour became a matter of notoriety. If one believes thus much, it requires no great stretch of faith to believe the statement that it was at her wish and instigation that the ornaments were given to the church, as offerings and vows for their mutual safety. Now, the veracity of the whole of the anecdote may be very well doubted, when we find in Nelson’s diary when he was at Gibraltar, on the 20th July, 1805, the following observation:

– “I went ashore for the first time since June 16th, 1803, and from having my foot out of the Victory two years, wanting ten days.”

In another letter dated about the same time, and addressed to Mr. Foresti, at Corfu, is this passage: – “Not a ship in this fleet has been into any port since the war; and to this moment I have never had my foot out of the ship.”

It was stated, also, by the Duke of Clarence, who had ascertained the fact, that Lord Nelson never went out of the Victory but three times, and then on the King’s service, from his leaving England, in 1803, to his return in 1805; and none of these absences from his ship exceeded an hour.

As his first visit to La Madalena was on the 31st October, 1803, and he left it for the last time on the 19th of January, 1805, it is quite clear, according to his own statement, that he never went ashore during nearly fifteen months he passed there. We know, moreover, that in 1804, when the Royal Sardinian family were fugitives from Piedmont, and under the protection of the British at Cagliari, he was pressed to visit them, but declined the honour with the excuse that his duty required his presence on board. These statements and circumstances, though not a positive refutation of the report, are sufficient indirect evidence to counterbalance the probability of the fact.

But, whether the anecdote be true or false, the name of Nelson is revered; and his candlesticks, whether the offering of love or religion, are no less objects of the highest interest to the Ilvese. The presence of his fleet was, as I heard from various authorities, a source of as much pecuniary advantage as gaiety; and their kindness, amiability, and good behaviour, seem to have left a favourable opinion of our nation. Entertainments and amusements of all kinds were in constant succession; and the victualing of so large a fleet was a profitable business for the Gallurese, as well as the Ilvese; the contraband trade with Corsica being also carried on to a greater extent than it even now is. The departure of Nelson and his fleet was, as the Ilvese say, “un colpo di apoplessia” on them; and it is, therefore, not without cause that they now complain of the great change that has taken place, and express their discontent at their present want of vitality.

These observations relative to Napoleon and Nelson, may have occupied too much space; but the circumstance of so insignificant and almost unknown a spot, having been the scene of the defeat of the one at the commencement of his career, and the head-quarters of the other during that which he considered the most anxious period of his life; namely, his endeavours to capture his rival’s fleet, may be some apology for their length.

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

19th Century Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs (captions translated freely)

Nicola Benedetto Tiole, “Inhabitants of La Maddalena”, ca 1819-1826, IN Nicola Tiole, Album di costumi sardi riprodotti dal vero (1819-1826), Nuoro, Isre 1990.

Nicola Benedetto Tiole, “Well-off inhabitants of La Maddalena”, ca 1819-1826 op. cit.

Agostino Verani, “La Maddalena islanders”, ca 1806-1815, IN Scoperta della Sardegna. Antologia di testi e autori italiani e stranieri, a cura e introduzione di Giuseppe Dessì, Milano, Il Polifilo, 1967.

François Geoffroi Roux, “The corvette Astrolabe around 1826”.

Louis Albert Bacler D’albe, “General Bonaparte”, 1796.

Denis Auguste Marie Raffet, “Bonaparte makes his debut in Sardinia”, 1826.

John Francis Rigaud, Captain Horatio Nelson, 1781.

Samuel Atkins, A squadron of the royal navy running, ca 1800.

George Lucy Good, Lord Nelson before Trafalgar, ca 1854.

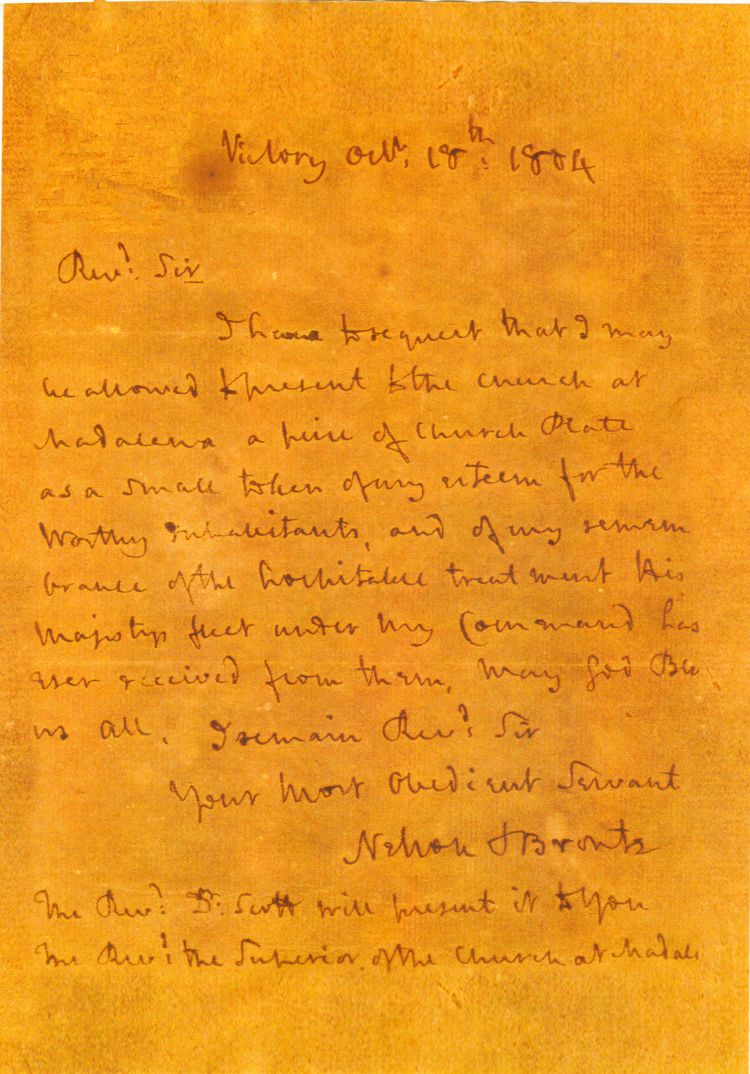

“Nelson’s letter for the gift to the Church of La Maddalena”, by www.santamariamaddalena.net

Lemuel Francis Abbott, Horatio Nelson, 1798.

Jacques Louis David, Napoléon Bonaparte, 1802.

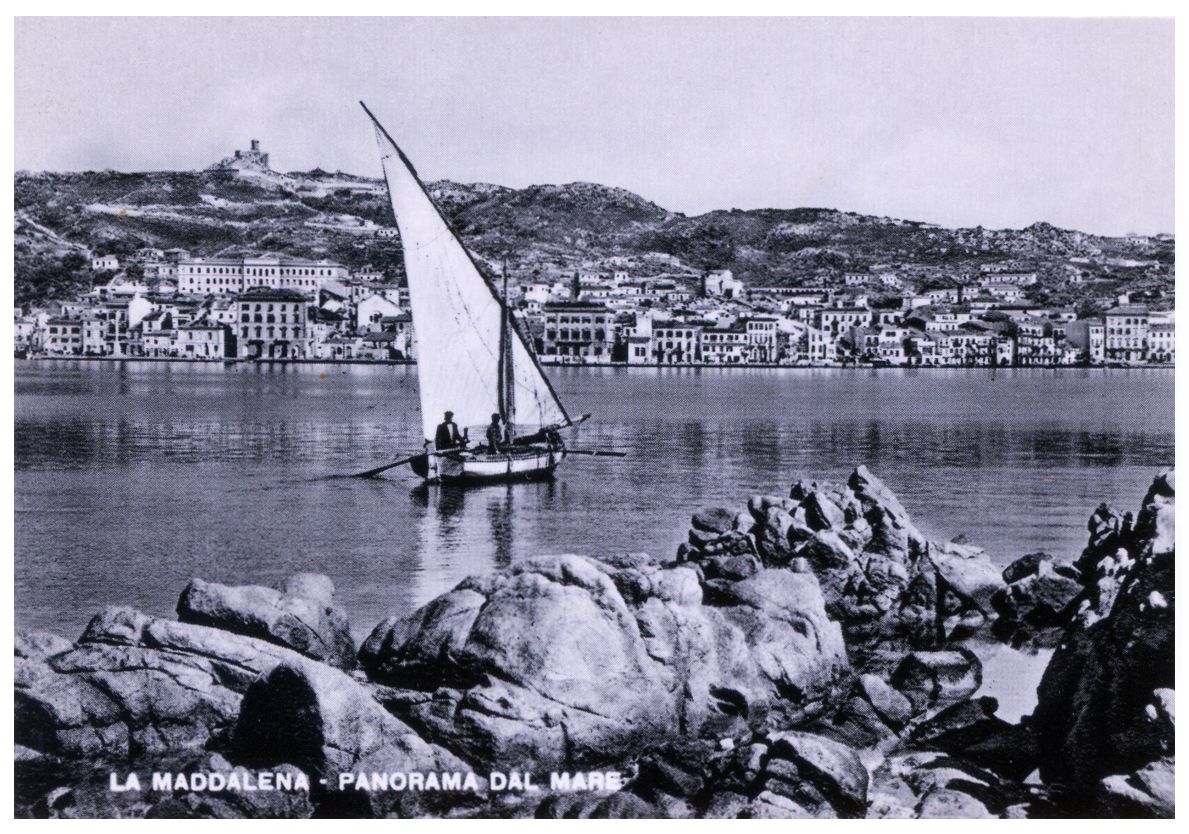

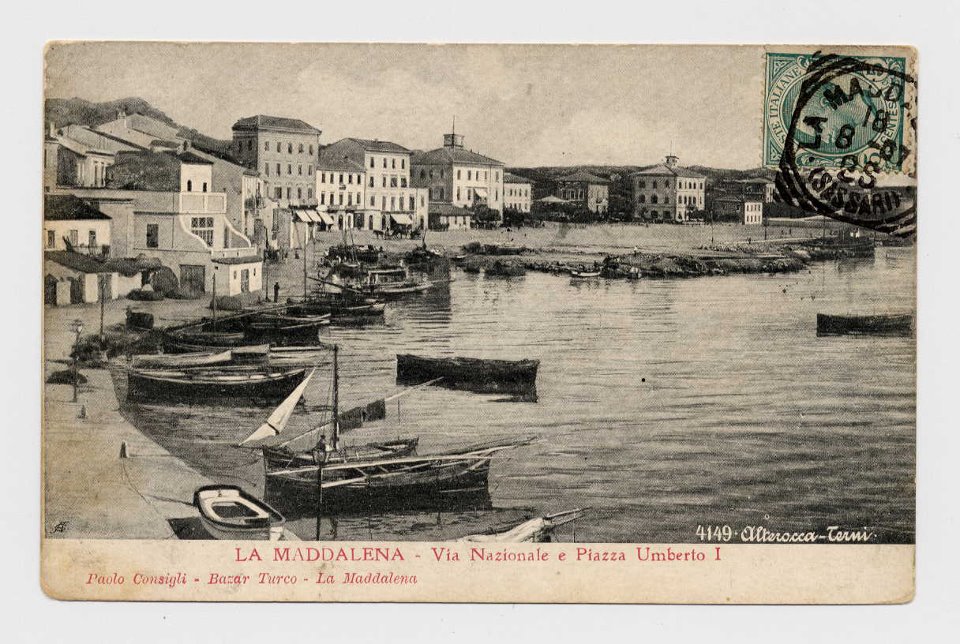

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

by www.lamaddalena.info and Antonio Frau

Contemporary Photos

Nello Anastasio – Flickr; Salvatore Zizi – Flickr; Matteo Merlin – Flickr; Idili e Chironi – Flickr; Roberto Oggiano – Flickr

Gianni Careddu – CC BY-SA 4.0, wikimedia commons; di Zamonin – CC BY-SA 3.0, wikimedia commons; Victory, di MARC912374 – CC BY-SA 4.0, wikimedia commons; di NASA – wikimedia commons; di Carlo Pelagalli – CC BY-SA 3.0, wikimedia commons

One of “Napoleon’s bombs”, at the Palace of the Municipality of La Maddalena; crucifix, candelabra and letter of Nelson: photo courtesy of Antonio Frau