ARZACHENA: HONESTY AND COURTESY OF BERGERS

by John Warre Tyndale

The Island of Sardinia

London 1849

Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street. Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty

in italian: ![]()

From Palau to Arzachena

On returning from the island of La Madalena to Sardinia, my route over the mountains and valleys from Parao to Terranova was through a continuous wilderness of forests and flowers, with the exception of a few “tanche” and occasional patches of pasture.

Theocritus may proclaim his native country to have been Flora’s peculiar garden; and our early ideas are by his idyls and the praises of other poets, prejudiced in favor of Sicily; but any traveller who has visited both islands, would decidedly give a preference to Sardinia.

The perfume of the cistus, with which the country for miles around was covered, was so overpowering as to be positively obnoxious, and this species of the cistaciae, as well as the helianthemum, being remarkable for the early shedding of its petals, the beautiful and delicately white blossoms gave an appearance of snow or a heavy hoar frost. No extracts or essences are made from the resinous secretion of the plant, as is the case with the cistus Creticus, from which the gum Labdanum is obtained; and, in gazing on the country blanched by these exquisite flowers, one is reminded of the extravagant price given, in the winter season, at Paris, for a single bouquet of this plant nearly as many francs as would purchase an entire acre of land in this district of Gallura.

Though many of the wild flowers which shed their perfumes in every direction, have been previously mentioned by name, a catalogue of some of them is given […]

Lilia, Caltha, rosse Baccar, Lotos, Hyacinthus, Combretum, Polion, Thimus, Anetha, Crocus, Liria, Vaciniuoi, Convolvous, Althea, Menta, Phirema, Ciclaminus, Timbre, Ligustra, Coris, Nardus, Anemona, Epithimon, Narcissus, Acanthus, Chrisitis et Cyamon, et Saluina virens, Cythemis, Enanthe, Holochrysos atque Cherinto, Lichnis, Amarantus, Casia, Melitolos, Puipureique tori Setureta, et Origana et Alga, ecc.

Arzachena

Ascending from these parterres, the path winds over hills covered with oak and cork forests, from which, together with the districts of Luras and Logu Santu, the finest cork is collected. Owing to their extent, the want of paths through them, and difficulty of communication with the shore, cork cutting is a much more expensive operation than in Valencia and Catalonia. Seven or eight contractors have at present a monopoly of the trade, but the abundance of untouched forest would yield a good profit to other speculators. […]

In this wild region is an exquisite spot called St. Maria di Santa Arsachena, a concentration of all that is romantic and pastoral.

Several streamlets descending from the mountains join and empty themselves in the gulf of Arsachena, forming by their union a deep and rapid stream, in which the quantity of fish was almost incredible.

“Our plenteous streams a various race supply: The bright-eyed perch with fins of Tyrian dye, The silver eel, in shining volumes rolled, The yellow carp, in scales bedropped with gold; Swift trouts, diversified with crimson stains, And pikes, the tyrants of the watery plains.”

This habitation – a specimen of those made of dried mud, turf and straw, where granite or some other material is not more easily and cheaply obtained – was about twenty feet square, by ten feet high; had no window except a small aperture about a foot square, and the roof consisted of large pieces of cork laid loosely on each other, with heavy stones placed on them to prevent their being blown away.

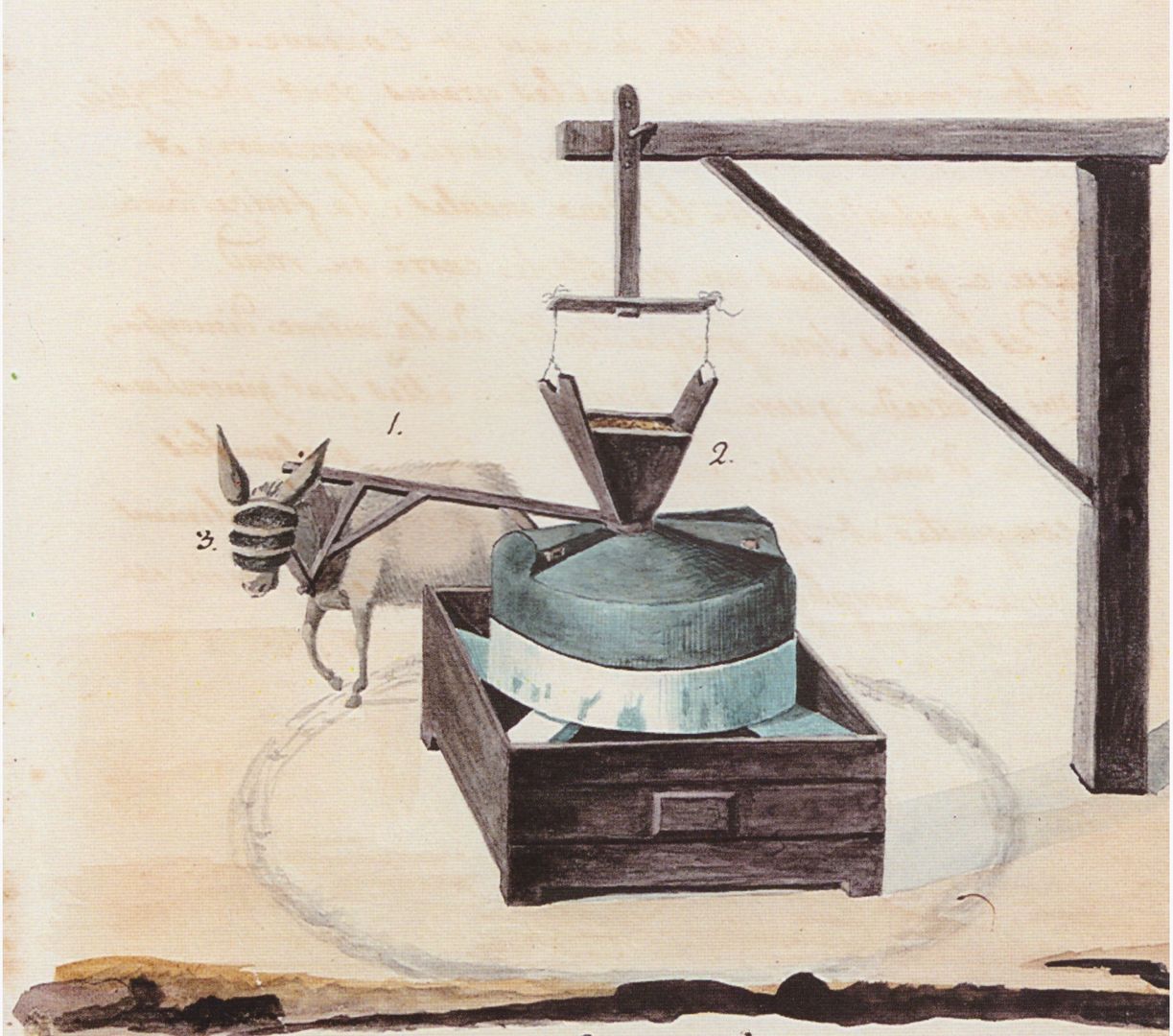

In the corner opposite the door was a flour-mill, worked with a short horizontal shaft by a miserable donkey, smothered up in a sheepskin cap over his head and eyes. Whether it was in tender consideration for any giddiness he might feel in revolving in his small circle, or that he might more fully appreciate the “grata superveniet quae non sperabitur” blow of a thick stick, is immaterial; but the head-dress, if it had not a useful, had certainly a very grotesque appearance.

Above the fire, on two rafters crossing the roof, was a reed lattice-work, on which were cheeses placed to dry and get a smoky flavor, a peculiar but highly esteemed quality; against the wall were hollowed trunks of trees filled with corn and other stores, some of them literally family trunks, being used as such for their clothes; and in smaller hollowed stems were cheeses steeped in salted water, while other kinds were on shelves or heaped upon the ground.

The household utensils, made of cork, bark, and split reed, were of a similarly rude construction and shewed not the remotest attempt at comfort or cleanliness. The only two stools, instead of their ordinary purpose, were used as stands for milk-bowls, and the custom of sitting on the ground is necessary, as the inhabitants thereby are less exposed to the smoky atmosphere of the room.

Outside the door were two upright poles supporting a horizontal one, from which were suspended buckets of water, to be softened by exposure to the night air.

Having crossed himself, he began to unpack it, and seeing the mother and daughters place themselves on their knees before him, and my cavallante as well as my guide take off their caps, I imagined some holy rite was to be performed, and accordingly I likewise uncovered.

After a minute’s suspense, he held the box forward to the members of the household; each of them affectionately embraced it, and this holy kiss was repeated two or three times; but when it came to my turn, and I refused to follow their example, their dismayed looks shewed the doubt which they subsequently expressed of my belief in Christianity.

The object of all this wonder was a small wooden doll’s head, the eyes and nose of which were just distinguishable; the rest of the figure was covered with a brocaded silk petticoat, and around the head was a gilt and silver tinsel glory, with the usual appendages of such images.

The ceremony being over, I inquired the name and history of the tawdry puppet, and could only obtain the highly authentic and satisfactory information that it was the relic of a Gallura saint; but all endeavors to elicit from the saint’s carrier and guardian, who she was, and when and where she lived, met with the invariable answer, “Senza dubbio la reliquia d’una Santa del Paese, ben conosciuta da per tutto.”

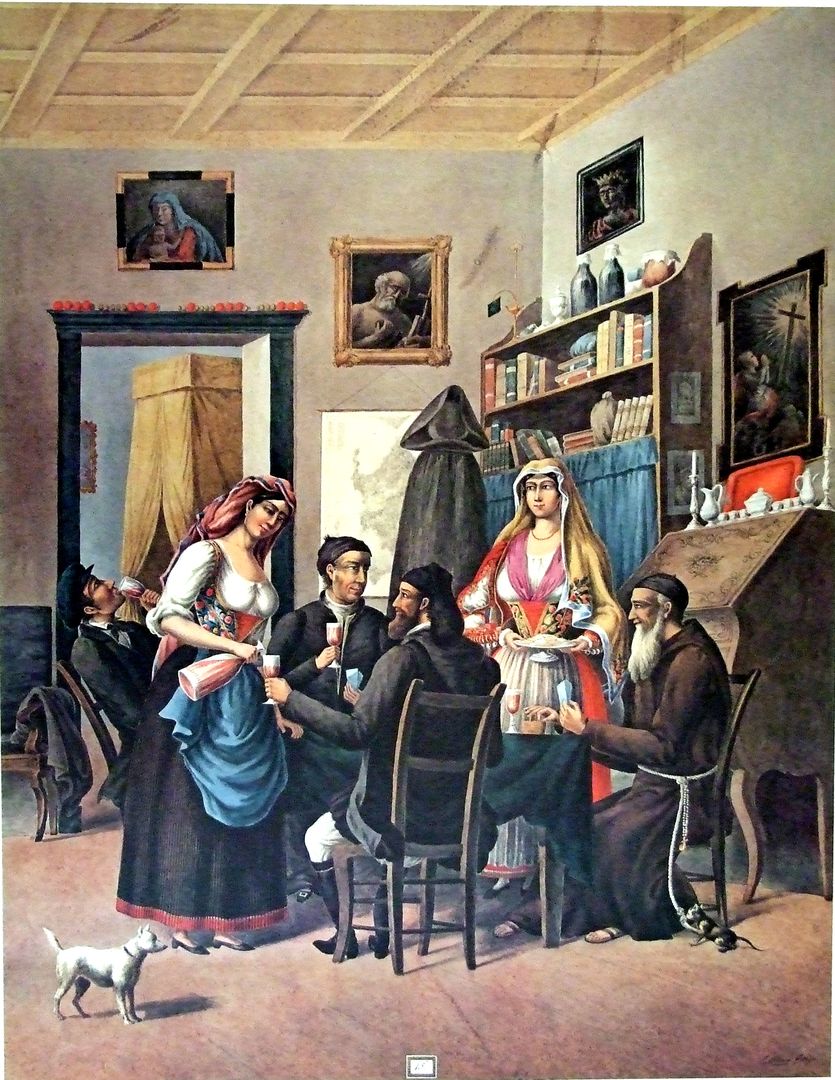

I found subsequently that it is a prevalent custom for some of the religious orders, especially the Mendicant Friars, to send any relic they possess to the different districts; and that the exhibition and privilege of worshipping and kissing it, are paid for by the contributions in kind of whatever eatables the worshippers may chance to possess.

According to the expression of the family, “the Virgin Mary would hear their prayers for having given cheeses to the saint;” a belief not surprising; for their extreme ignorance of everything, religious as well as worldly, their rare intercourse with their fellow-creatures, and having neither instruction nor church within reach, make them a connecting link between civilised man and the animals in their “cussorgie.”

In mentioning this circumstance to a village priest in another part of the island, he not only defended his fellow-idlers in the Lord’s vineyard, for not visiting the peasants, but attempted to demonstrate that religious instruction was positively conveyed by sending the image and obtaining contributions by its means.

If the ignorance and superstitious credulity of my present hostess were great, her hospitality and generosity were no less; she soon recovered from her momentary horror of my heretical irreverence, and, though not the bearer of a holy relic, it was with some difficulty I could get away without having several cheeses put into my saddle-bags; and when my repeated assurances that I was not partial to them at length induced her to desist, she wanted to send to her husband to bring me home a kid or a lamb. She would have considered it an insult to have been offered any payment for her gifts, had they even been accepted; and, after repeated expressions of her wishes to supply me from her humble store, we parted with a shower of mutual benedictions.

“Shepherd, I take thy word, And trust thy honest offered courtesy, Which oft is sooner found in lowly sheds With smoky rafters, than in tap’stry halls And courts of princes, where it first was named. And yet is most pretended.”

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

19th Century Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs [captions translated freely]

Nicola Benedetto Tiole, “Mill from Sardinia”, ca 1819-1826, IN Nicola Tiole, Album di costumi sardi riprodotti dal vero (1819-1826), saggi di Salvatore Naitza, Enrica Delitala, Luigi Piloni, Nuoro, Isre 1990.

Alessio Pittaluga, “Shepherdess from Gallura”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes par A. Pittaluga [lithography engraved by Philead Salvator Levilly], Paris – P. Marino, Firenze – Antonio Campani, 1826, rist. Carlo Delfino 2012.

William Light – Jean [Giovanni] Micali, 1829-1830 (1 – 2 – 3)

Alessio Pittaluga, “Shepherd from Gallura”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes par A. Pittaluga op. cit.

Giuseppe Cominotti, “Country conversation”, 1826, IN Francesco Alziator, La raccolta Cominotti: raccolta di costumi sardi della Biblioteca Universitaria di Cagliari, ed. De Luca 1963 e Zonza 1990.

Simone Manca di Mores, “The master […] with the friar and other friends”, ca 1861-1880, IN Simone Manca di Mores, Raccolta di costumi sardi. Commenti alle tavole di Luigi Piloni e Antonangelo Liori, Cagliari, Della Torre, 1991.

Lorenzo Pedrone, “Shepherdess from Gallura”, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

coll. Francesco Cossu

Contemporary Photos

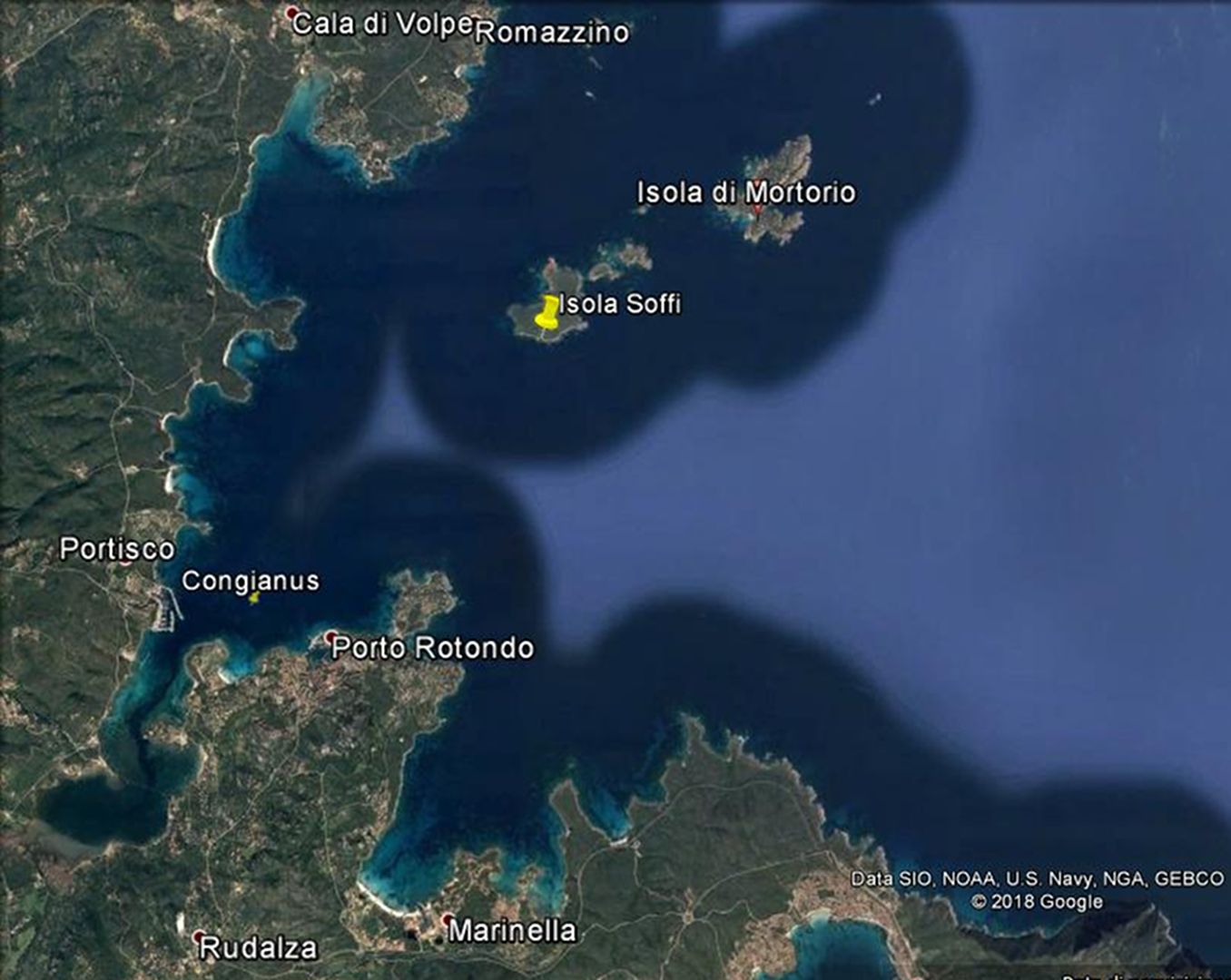

google earth, Winkelbohrer – CC BY-SA 2.0 – Flickr, di Marco Melzi, Flickr, Luca Farneti – Flickr, Vittorio Ruggero – Flickr