ARZACHENA

Sketch of the present state of the Island of Sardinia⇒

London 1828

John Murray, Albermarle-Street

in italian: ![]()

The bay and coat of Arzachena

Northward of Figari, a deep bay reaches to Cape Libano, with several bare islets off its northern shore, of which Mortorio and Soffi are the principal: the whole group is collectively called “i Mortorii”, and is said to have derived this name from the dreadful carnage suffered by the Pisans, in a battle with the Genoese, that took place close to them.

These mountains are intersected by the fine, well-watered, and extensive, though uncultivated, plains of Liscia, Arsaquena, and Congianus; the flocks and herds of which are tended by a few straggling peasants, who quit the towns of Luras and Tempio, after the feast of All Souls, and remain till the end of June; when, to avoid the intemperie, they repair to their habitations. During this time they are occupied with their dairies, and the making of coarse cheese; each peasant also cultivates a small piece of ground for wheat and barley, merely sufficient for the support of his family. […]

These fine grounds are watered by a meandering stream, which, though nearly dry in August, is never actually so: it contains trout, perch, and eels, and its shallow parts swarm with tortoises. In their respective seasons there is also an abundance of partridges, quails, doves, beccafichi, and many other birds; especially the beautiful “apiolu,” or bee-eater, which works its nest in horizontal galleries, deep sunk into the banks of the river. […]

The festivity of Arsequina

The periodical festivities of the Gallura are of a more peculiar stamp, combining rusticity and hospitality, with independence and ferocity. The principal of these are celebrated at Arsequina and Logu Santu; and being precisely similar in their practices, a description of the former will suffice.

It occurs on the third Sunday in May: we landed on the Saturday, and rode up to the chapel of Santa Maria, which, with two other small buildings, are on a beautiful hill covered with trees, except in front, where an open spot overlooks a woody plain.

The feast is regulated by a company of thirty or forty Capo Pastori, entitled the I “soprastanti” of the ceremonies; each of whom must provide a sheep or goat, twelve pounds of cheese, and thirty of bread; and they must jointly furnish oil, candles, fuel, cooking utensils, and four or five hundred bottles of wine, on which all comers are gratuitously regaled. In a short time the scene derived great interest from the activity and bustle of such a multitude; and, under the canopy of heaven, various parties commenced dancing the “salto Sardo,” the “ballo tondo,” and the more lively pelicordina while, in other parts, poets were heard reciting their Amoebaean verses in coarse recitative.

After supper, the amusements recommenced, and continued throughout the night; those that were fatigued rested under the trees, so that, at day-break, I observed groups of men, women, and children lying in every direction — though there was no lack of merry people to keep up the dance and the song. One poet, in particular, continued till morning was far advanced, with a ditty that appeared deeply interesting to his auditors; but his voice was harsh and very monotonous. The atmosphere was beautifully clear; and the silvery moon, together with the dulcet notes of numerous nightingales, enhanced the pleasures of the night.

This chapel is the charnel-house of the shepherds of the vicinity, whose bodies are thrown into a large vault, without lime, forming such a revolting and offensively -putrid mass, that the “soprastanti” have been obliged to erect an altar for the celebration of prayer, outside of the edifice. Three men had been murdered by banditti, and thrown in without any ceremony by the shepherds, only a few days before my arrival; for there is no coroner’s inquest, to take cognizance of secret murder here. I was informed that a man, “sotto penitenza,” occasionally descends this disgusting cavern, to clear away the bodies from under the opening, precaution being first taken, to lower down and burn several torches.

I could not learn why there were no carabineers in attendance on this anniversary; but the consequence was a numerous concourse of banditti from the circumjacent fastnesses, notwithstanding the presence of a great many “barancelli,” who, it is known, will not arrest a man that “is only an assassin.”

Another circumstance that excited many remarks, was the extreme gaiety of two young priests, whose dancing and singing gave great offence to many of the grave elders: indeed, the regard of the country people for their religious observances is very remarkable; an instance of which I noticed at an entertainment, where much anger arose from a Piedmontese officer giving the name of “Spirito Santo” to a dish of stewed pigeons.

“”””SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

19th Century Paintings, Drawings, Maps and Lithographs [captions translated freely]

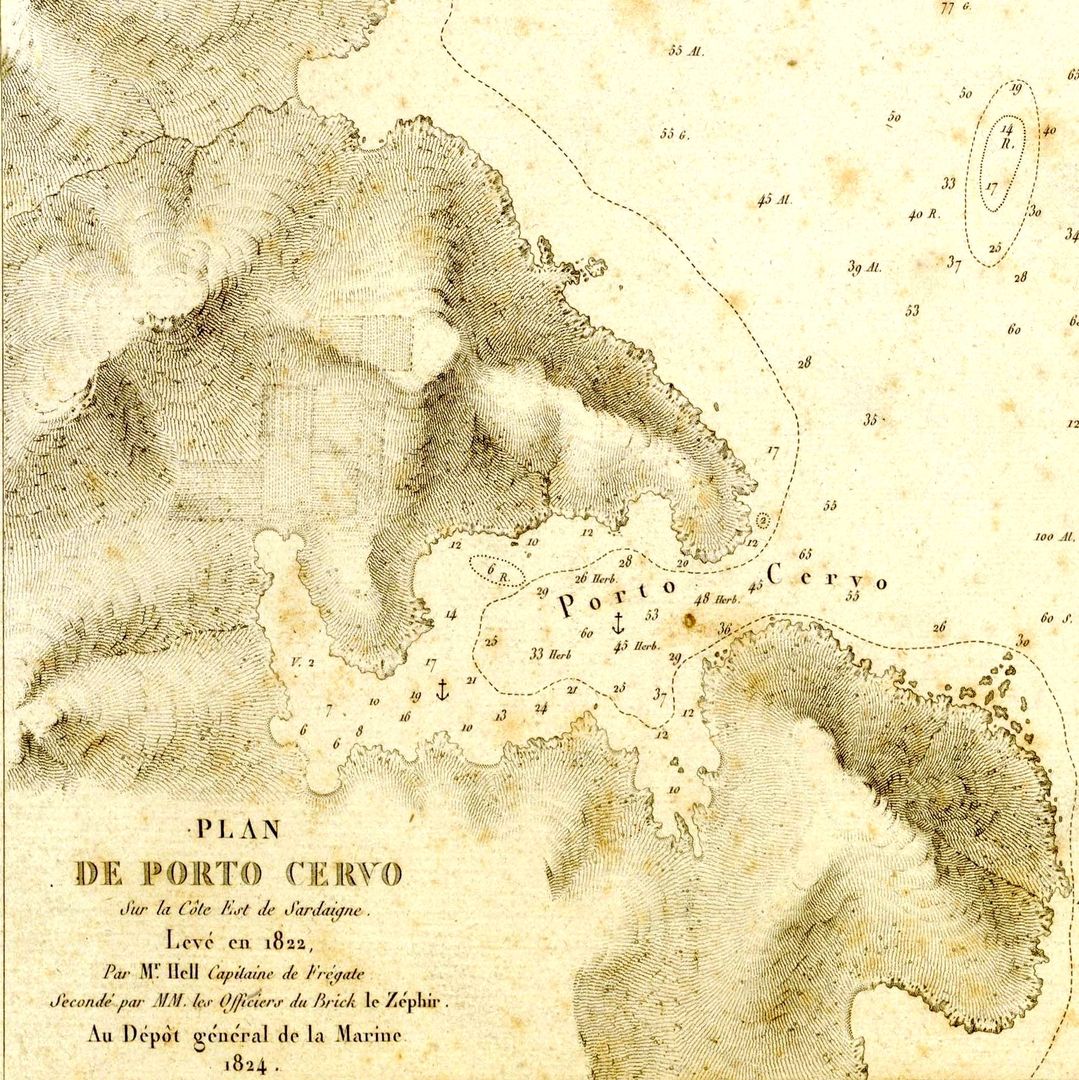

“Map of Porto Cervo”, 1822.

Alessio Pittaluga, “Shepherd from Gallura”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes par A. Pittaluga [lithography engraved by Philead Salvator Levilly], Paris – P. Marino, Firenze – Antonio Campani, 1826, rist. Carlo Delfino 2012.

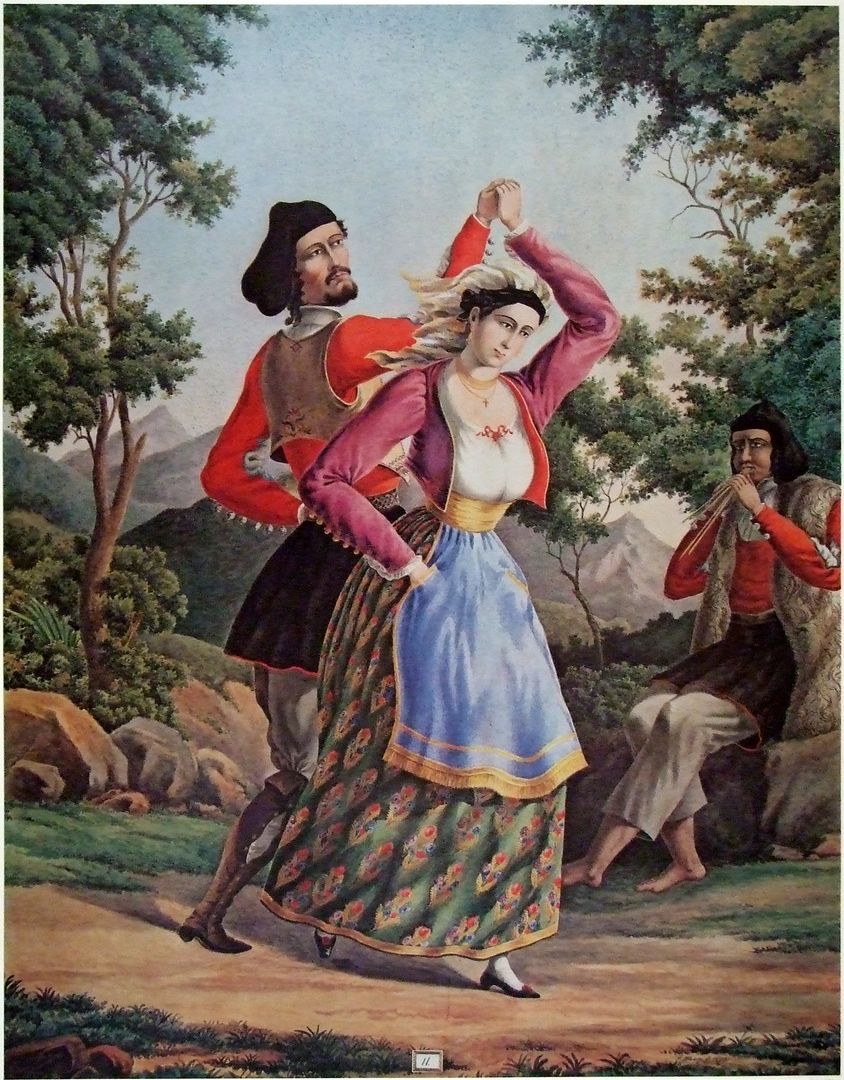

Giuseppe Cominotti and Enrico Gonin [drawing] – A.J. Lallemand [engraving], “Sardinian dance – Sassari region”, ca 1826-1839, IN Alberto Della Marmora, Voyage en Sardaigne, ou Description statistique, phisique… Atlas de la première partie, (1. ed. Paris, Delaforest 1826, 2. ed. Paris Bertrand, Turin-Bocca 1839).

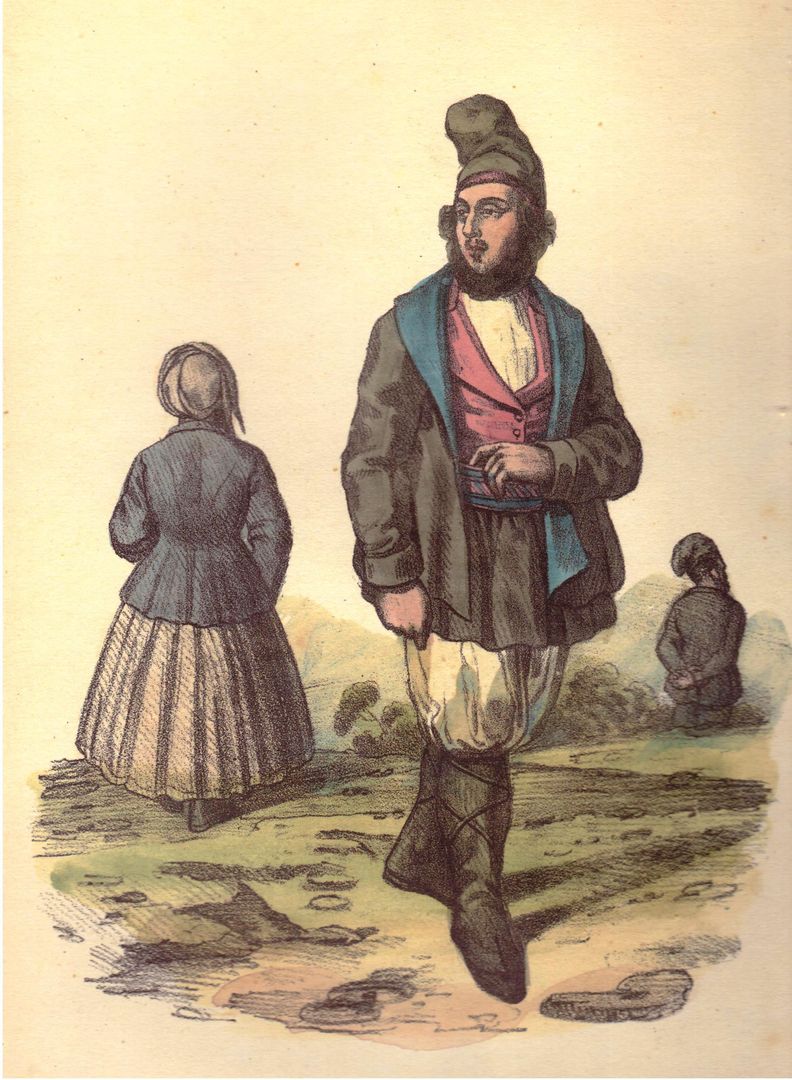

Alessio Pittaluga – Philead Salvator Levilly, “Country man of Tempio”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. op. cit.

Luciano Baldassarre, “Dress of Tempio”, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Alessio Pittaluga – Philead Salvator Levilly, “Shepherdess from Gallura”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux, op. cit.

Philippine de la Marmora, “Tempio district”, ca 1860, IN Luigi Piloni, Memorie sulla terra sarda: tempere inedite di Philippine de la Marmora (1854-1856), Cagliari, Fossataro, 1964.

Simone Manca di Mores, “Dance to the sound of the launeddas, ca 1861-1880, IN Simone Manca di Mores, Raccolta di costumi sardi, Cagliari, Della Torre, 1991.

“Old coat of arms of Tempio”, from rete.comuni-italiani.it

Lorenzo Pedrone, “Shepherd from Gallura”, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Luciano Baldassarre, “Round dance”, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna op. cit.

Giovanni Marghinotti, “Country holiday in Sardinia”, 1861, IN Gianpietro Dore, Giovanni Marghinotti nel Museo Sanna: esposizione delle opere nel bicentenario della nascita (1798-1998), Sassari, Stampacolor, 1998.

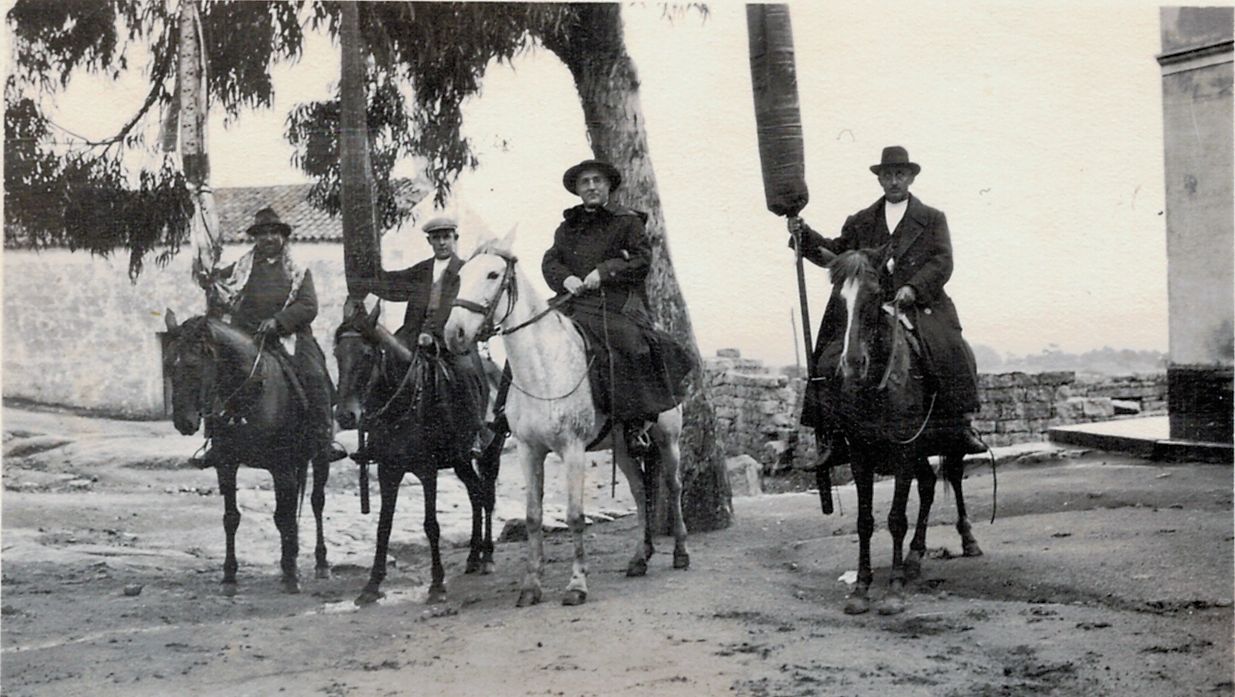

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

coll. Francesco Cossu

Contemporary Photos

google earth, Winkelbohrer – CC BY-SA 2.0 – Flickr, Luca Farneti- Flickr, Ökologix – CC0 – commons wikimedia, Salvatore Zizi- Flickr, Pieter Ter Kuile – Flickr, Marco Melzi, MB Engineering snc